On November 5th, while most of the political world was glued to the results in Kentucky, Virginia, and Mississippi – I was eagerly awaiting results out of rural Utah. San Juan County, located in the southeast corner of the state, has been the site of a major culture clash between the area’s conservative, white residents and the Navajo Nation Indian Reservation. The county is even split between Native Americans and Whites, and decades of rough relations have spilled over in recent years due to lawsuits of voting right and redistricting. This culminated in a tense and racially-charged referendum that took place this November.

Backstory

San Juan’s history is very long and complex. I recommend reading an article I wrote two years ago on the county, its history, and the gerrymandering lawsuit that was going on at the time.

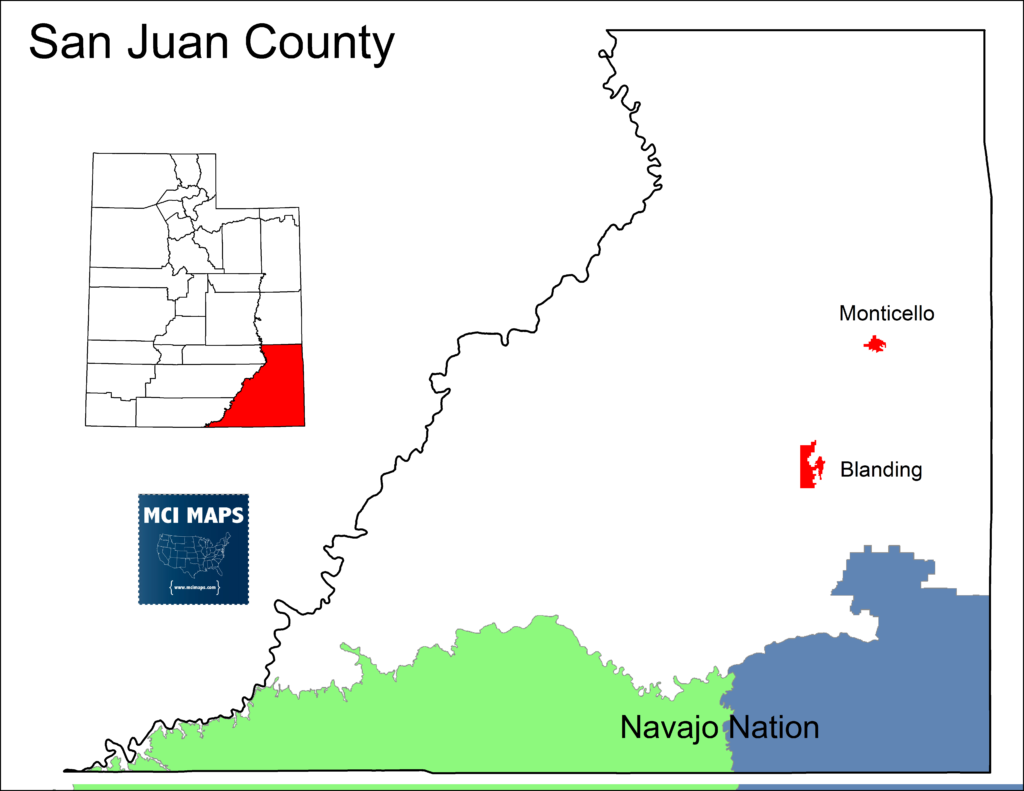

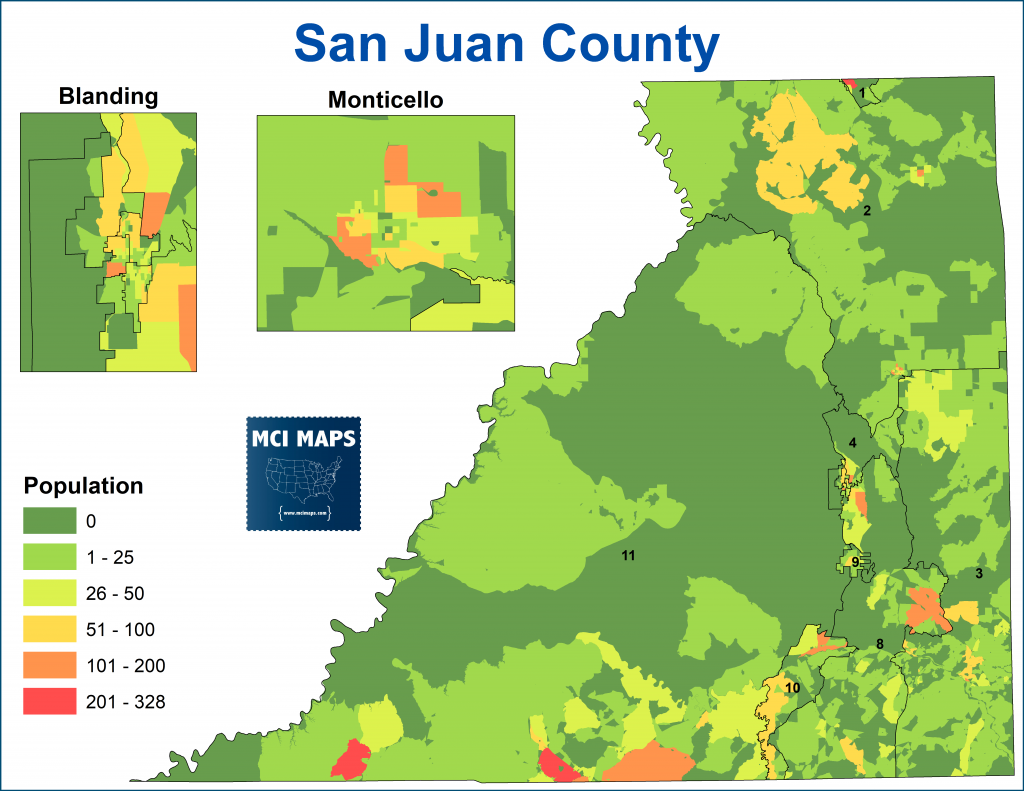

San Juan is a scarcely populated county that has only 15,000 residents but takes up 7,800 square miles. The southern end of the county is covered by the Navajo Nation Reservation. The two largest cities outside the reservation are Blanding and Monticello (the county seat).

The Navajo Nation portion of the county has more density than the rest and is part of the much larger Navajo Nation reservation – which spans multiple states.

Large swaths of land hold little to no residents. Many areas are federal land.

For a few decades, San Juan has been covered by a three-member county commission; each elected to a district. Elections used to be at-large, but a court order demanded single-member districts to ensure the Navajo had an opportunity to elect a member. Relations between the tribe and county government were always tense – with the county refusing to offer many services to the reservation – arguing the Navajo Nation should provide them. Court orders were needed to ensure school construction, bus services, and utilities. In the county, the Navajo have historically had weaker turnout than their white counterparts, meaning that county-wide races were won by white, Republican candidates.

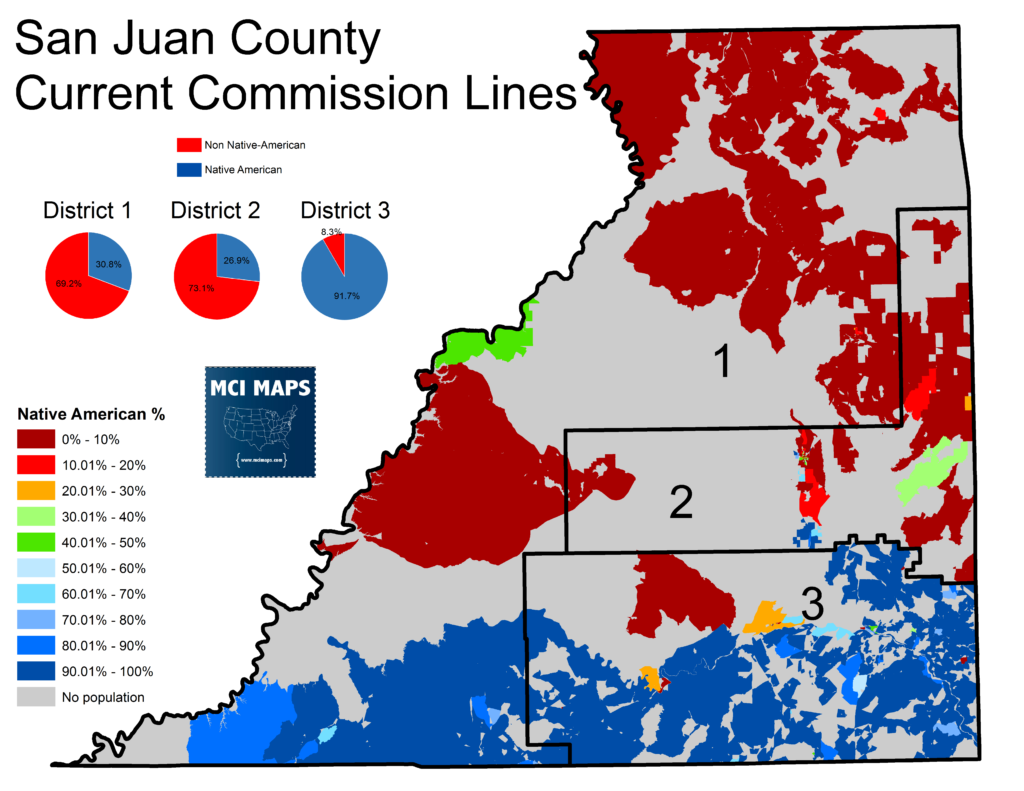

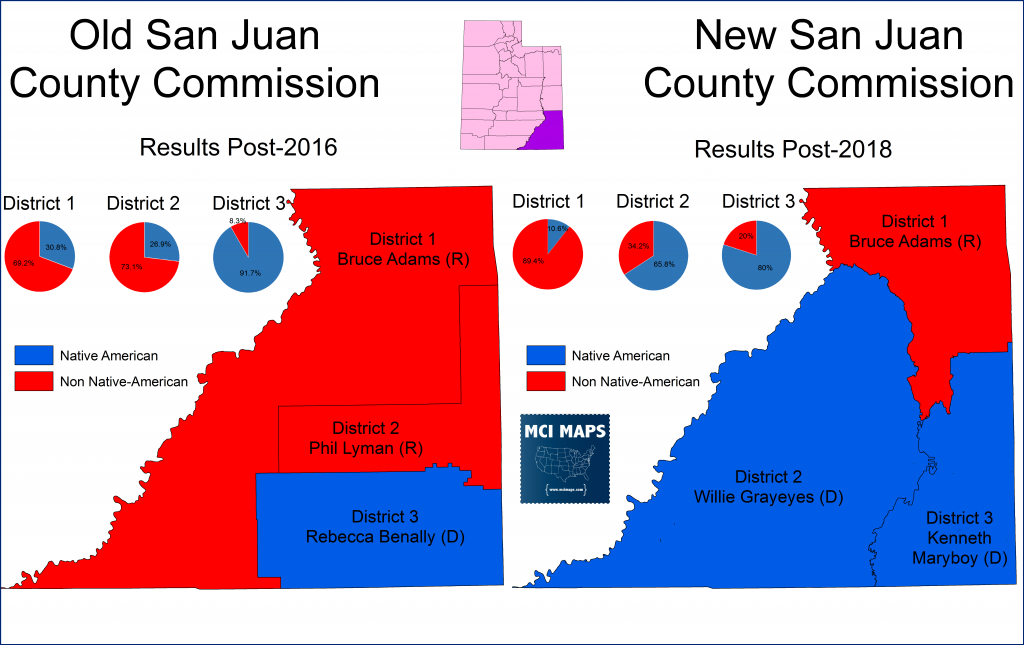

In response to the 1980s court order, the county drew three districts, which they did not change from the 1980s till a few years ago.

The map created one 90%+ Navajo seat, while leaving the other two heavily white. This created a constantly 2 white, 1 Navajo dynamic on the commission.

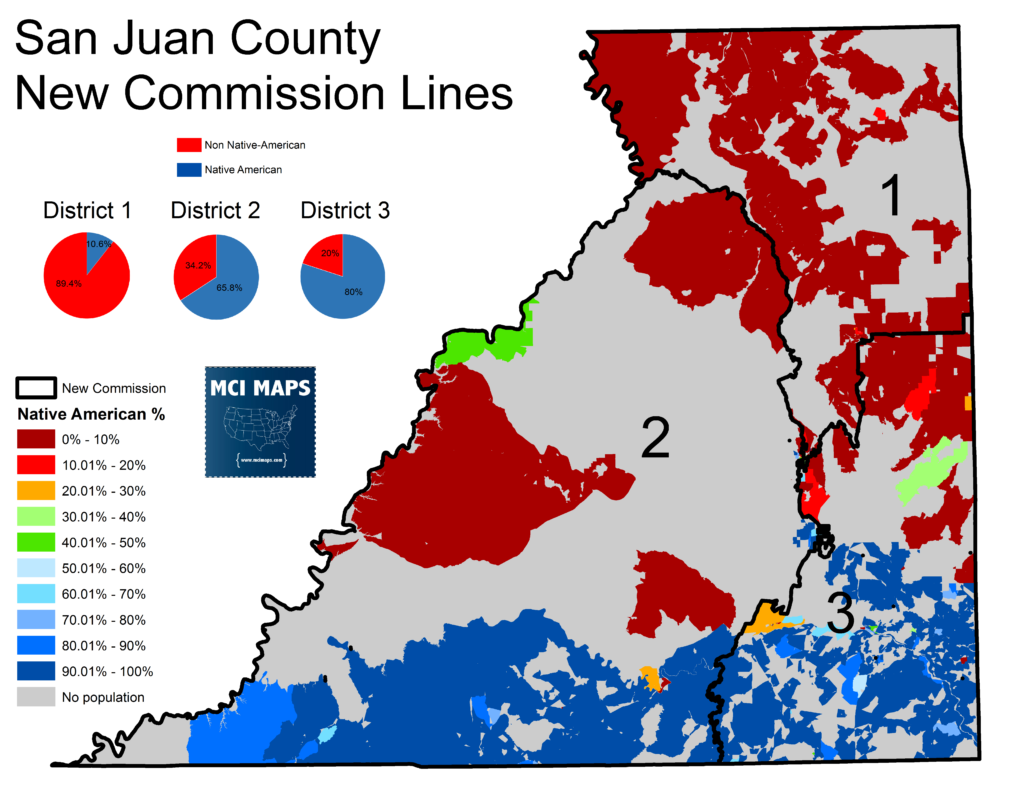

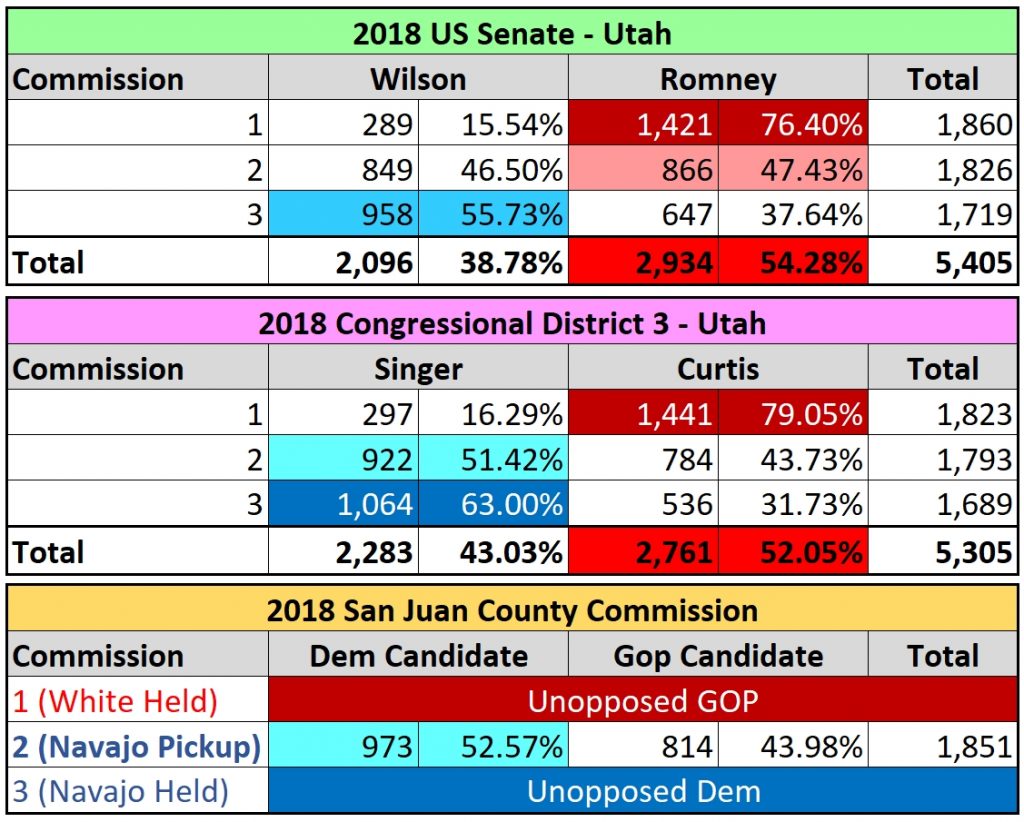

A federal judge struck the map down in 2016. A long redistricting process began, but new maps were finalized in 2017/2018. The new plan, drawn by a special master, created a safe Navajo seat, safe white seat, and a swing seat. The 2nd district, while 60%+ Navojo, was considered swingish due to the turnout dynamics previously mentioned.

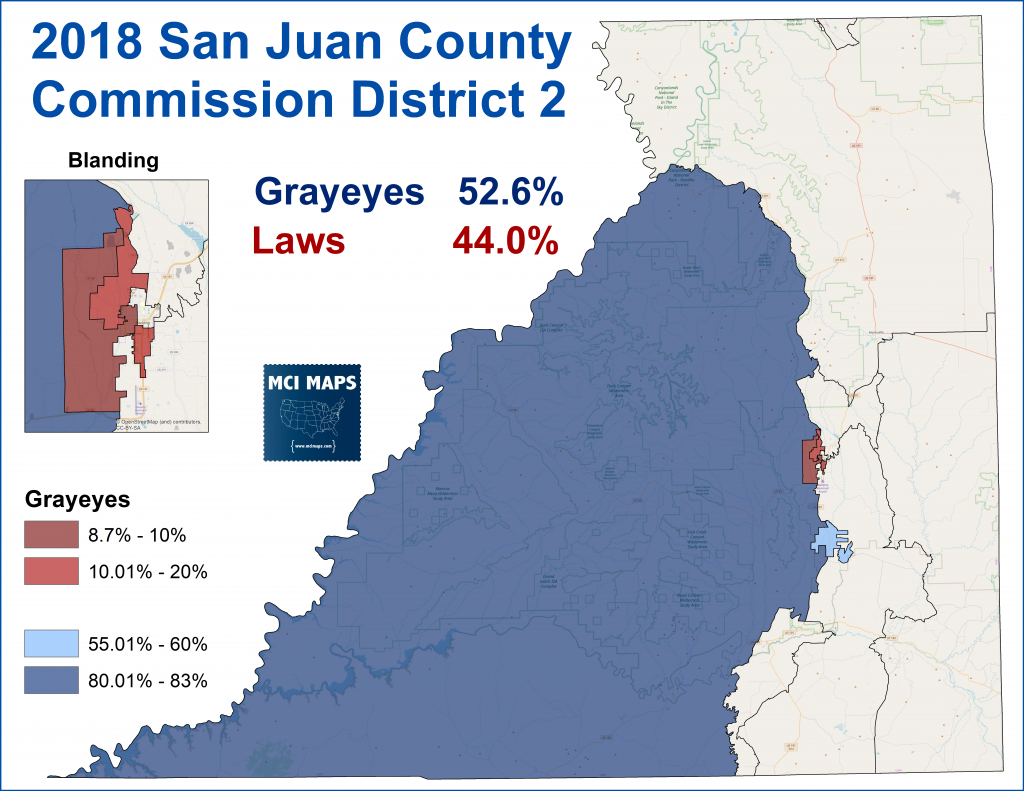

Appeals from the county government failed and the 2018 elections went forward under the new lines. The Navajo candidate was Willie Grayeyes, a reservation resident of Navajo Mountain. Before the election, opponents of the change tried to get Grayeyes tossed off the ballot, claiming he didn’t live in the county. This all stemmed from him having a PO Box across the Arizona border – something common in the area due to bad postal service in the reservation. The Clerk of Court threw him off the ballot, but a court ordered him back on and subsequently chastised the Clerk for his handling of the situation. In the end, Grayeyes won the election by 159 votes.

The precinct map of San Juan really misrepresents the situation. Grayeyes’s win in Navajo mountain (the big precinct) is largely in the southern end of the county – most of that northern portion is empty land. Meanwhile, Kelly Laws dominated in the Blanding region. The polarized voting (with only small little White Messa being close) highlights the tense racial dynamics in the county).

The result was the first Navajo majority commission in San Juan in over 100 years – it also meant a 2-1 Democratic majority.

The district did perform as a swing seat like the special master predicted. In addition to Grayeyes’ close win, the seat narrowly backed Mitt Romney for US Senate but then voted narrowly Democratic for congress.

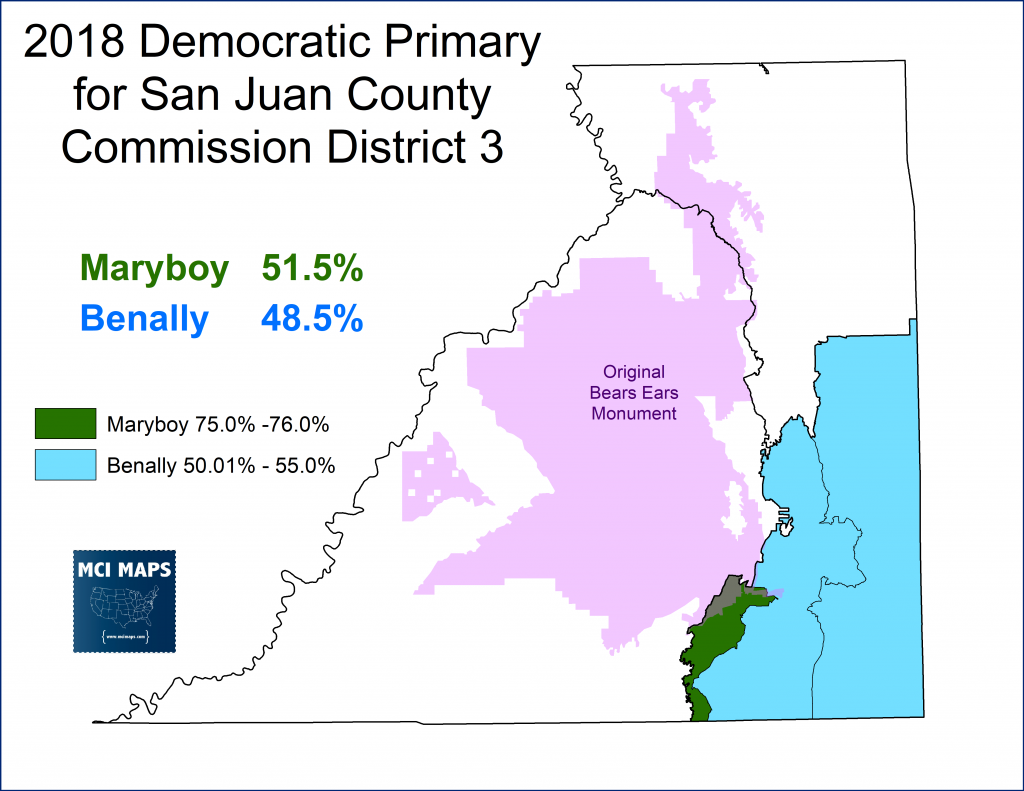

Earlier in 2018, a primary for District 3, the safe Navajo seat, saw Rebecca Benally lose to fellow Navajo Kenneth Maryboy, who was a former commissioner. Benally was a rare Navajo opponent to Obama declaring the Bears Ears National Monument. She even met with Trump and bragged about meeting him when he subsequently shrunk the size. Maryboy dominated in the west end of the district – in the areas around Bluff.

Grayeyes’ and Maryboy’s election allowed the commission to vote 2-1 in 2019 to oppose Trump’s move to shrink the Bears Ears declaration.

Both Navajo commissioners spent 2019 in lock-step on issues and votes on the commission were often 2-1. This may not have happened had Benally won her primary. The new dynamic angered the political establishment and meetings saw steady streams of white residents complaining about the changes in policy.

2019 Referendum

The situation reached a boiling point when Blanding Mayor Joe Lyman began a petition push to put a measure on the 2019 ballot. The measure, if passed, would have formed a study committee that would recommend changes to county government. The goal was to increase the county commission and get another shot at redistricting, something Lyman admitted to as he complained about the lines splitting his city. The split is unfortunate but it should be noted was upheld in courts because 1) Blanding still had strong influence in County 2 and 2) The population clusting meant some city was going to be split.

The referendum was a very heated affair. The Navajo Nation made a major push to defeat the proposal – engaging in a massive campaign against it. There were many concerning issues on top of Navajo turnout dynamics. This includes

- Issues with voting rights based on addresses

- Electioneering by the San Juan Clerk in favor of the referendum

- ACLU complaints that the county was not following agreed guidelines for voting on the reservation

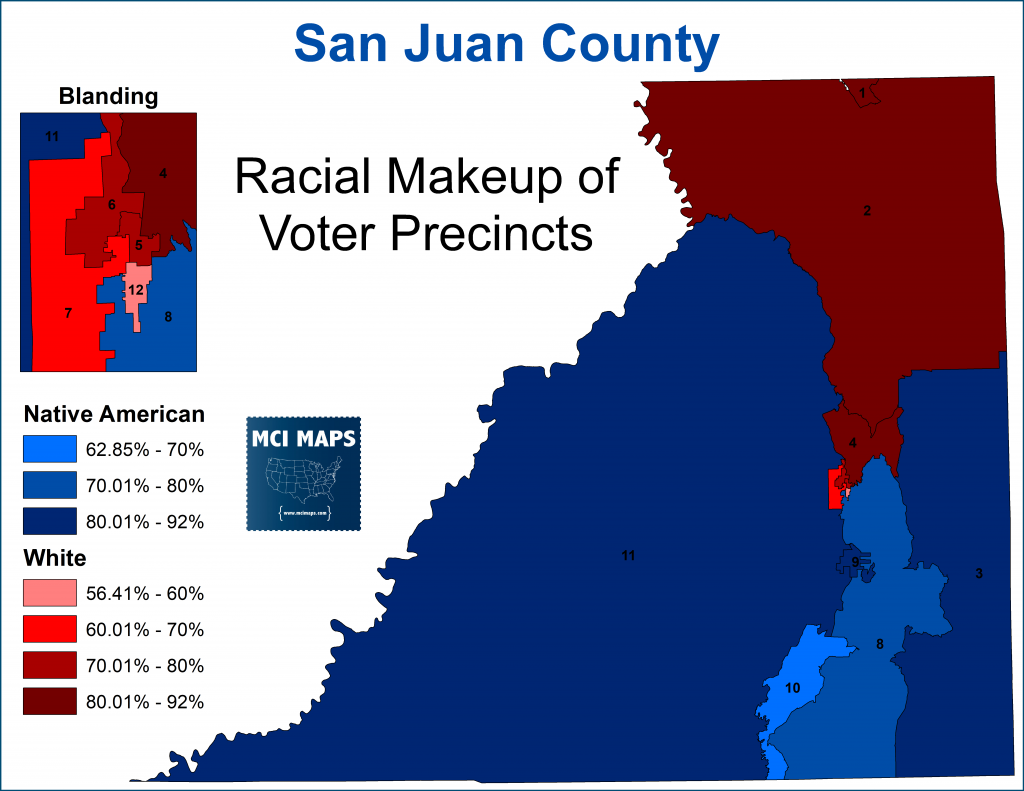

It was expected the results would be driven heavily by race. For reference, this is the racial makeup of San Juan’s voter precincts.

Heading into election day, I was not optimistic – convinced voter turnout would give the YES side an edge.

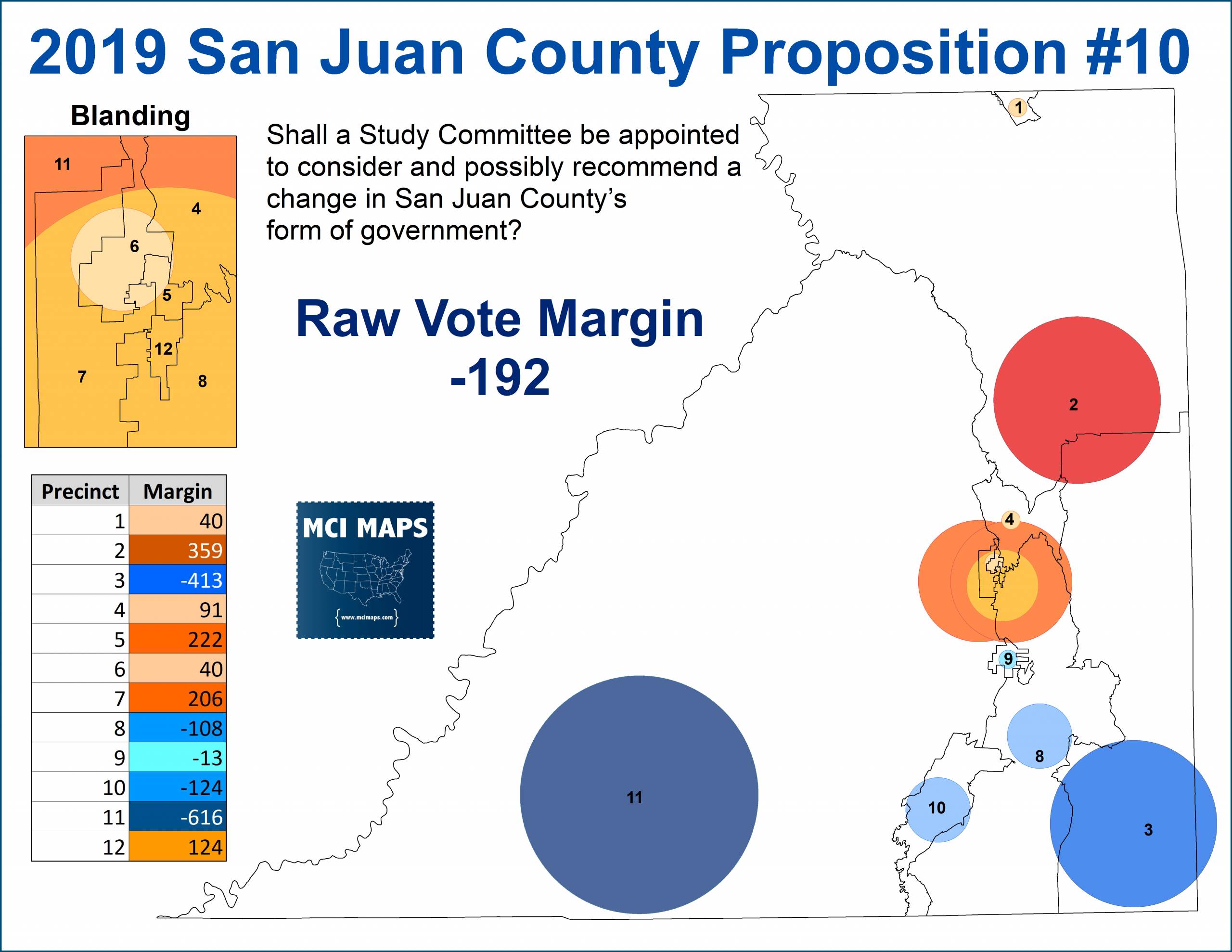

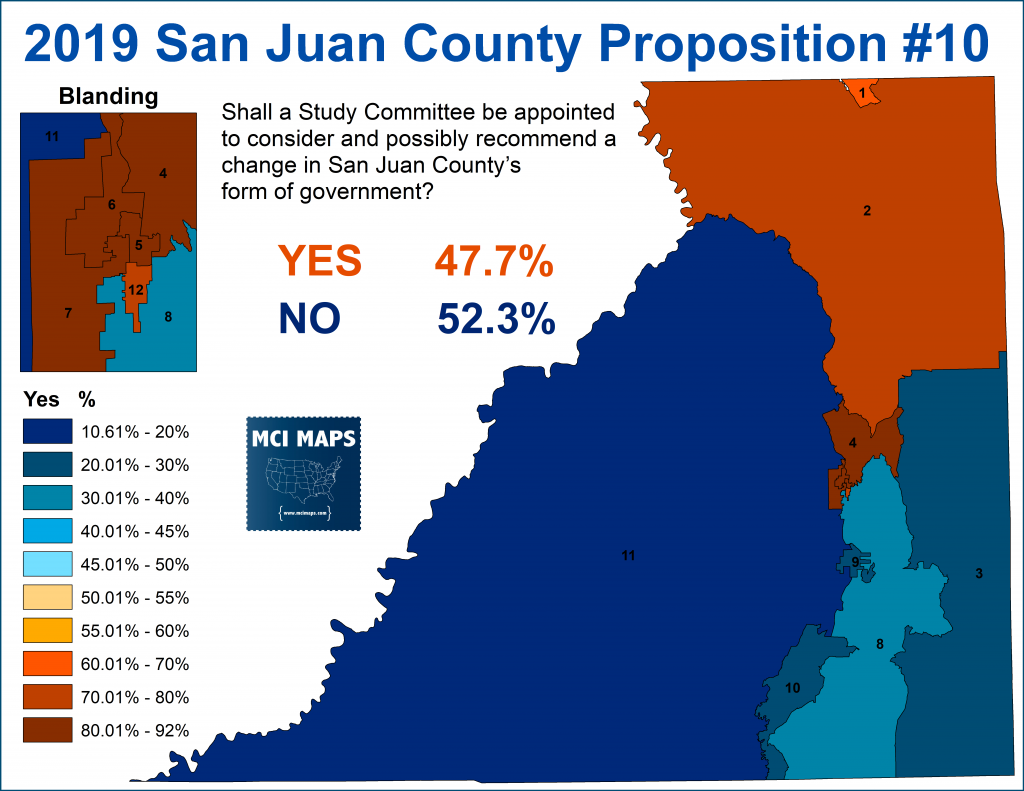

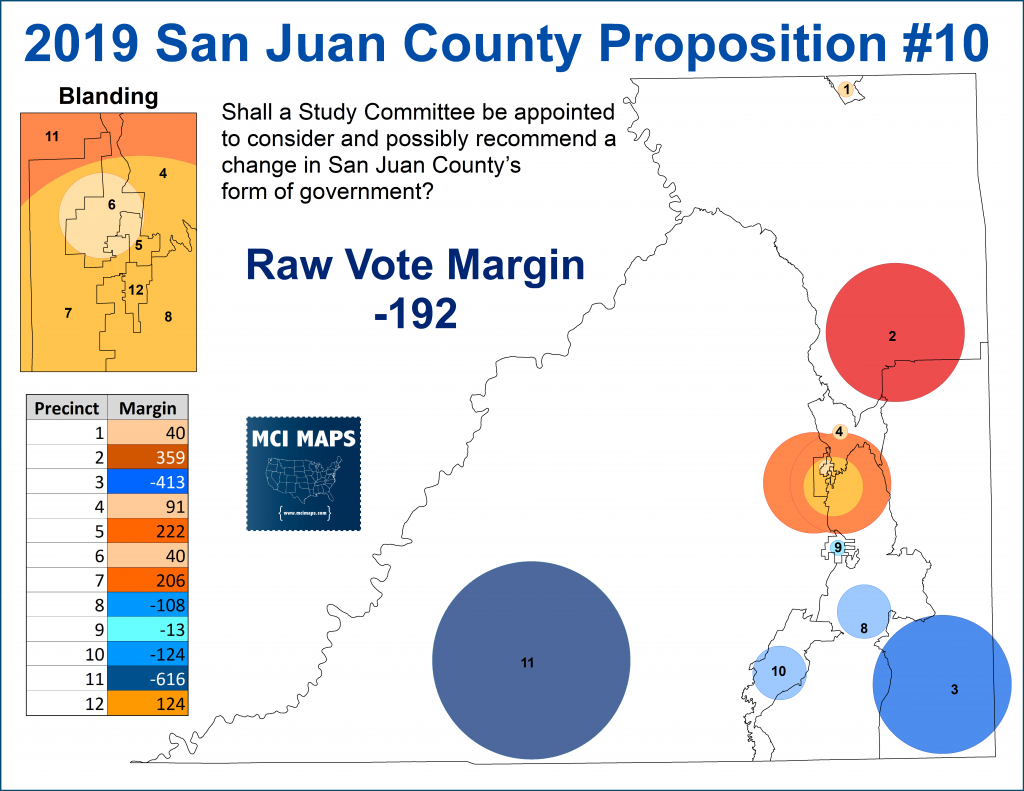

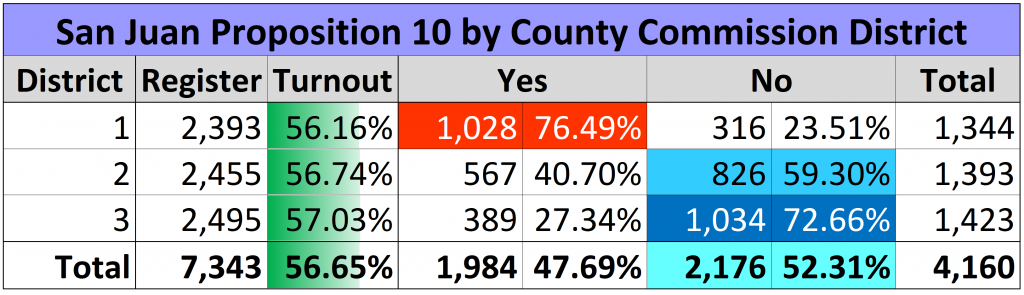

To the shock of many, including myself, the proposition failed with only 47.7% of the vote. The proposal fell just under 200 votes short. The results map has an uncanny mirror to the racial makeup of the precincts. All Navajo precincts heavily rejected the measure, while the white precincts all backed the proposal.

The proposal performed weakest in Navajo mountain, located in the Southwest corner of the county. Meanwhile, it racked up huge margins around Blanding.

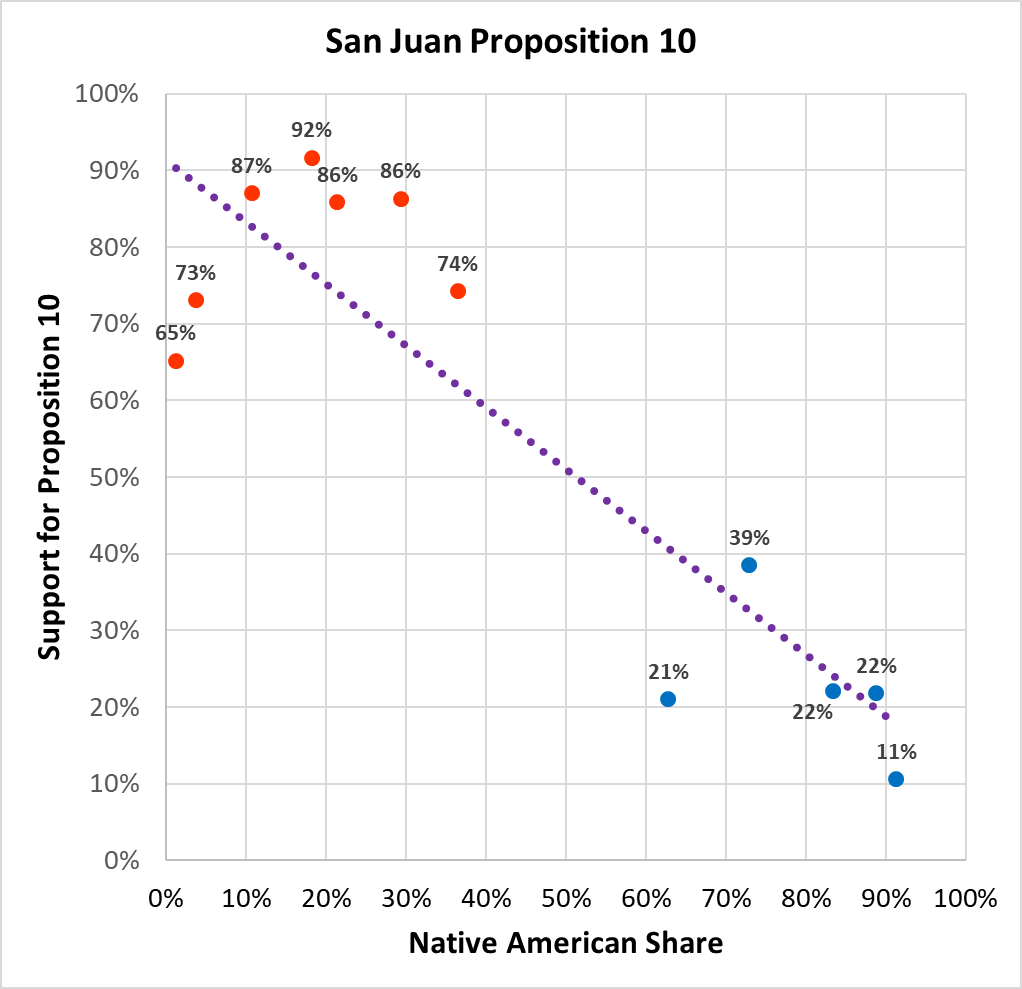

The trend between Navajo share of the vote and support shows a strong statistical correlation. The two precincts where the Yes % really seemed to under-perform the white % were in the far north of the county – around Monticello and up.

San Juan’s large size and empty geography means regular precinct maps can be misleading when it comes to displaying data. I created this map, with each precinct given a circle for the vote margin – with the placement of the circle close to the population density of that precinct.

Navajo Mountain, for example, is located in the southwest end but its precinct goes much further north (despite few living up there). The Navajo population is located largely in the bottom third of the county – and the old precinct maps pre-2018 better reflected that.

The best raw vote margin for the proposition came Monticello, but it did not boast the highest percent support.

Turnout Shocker

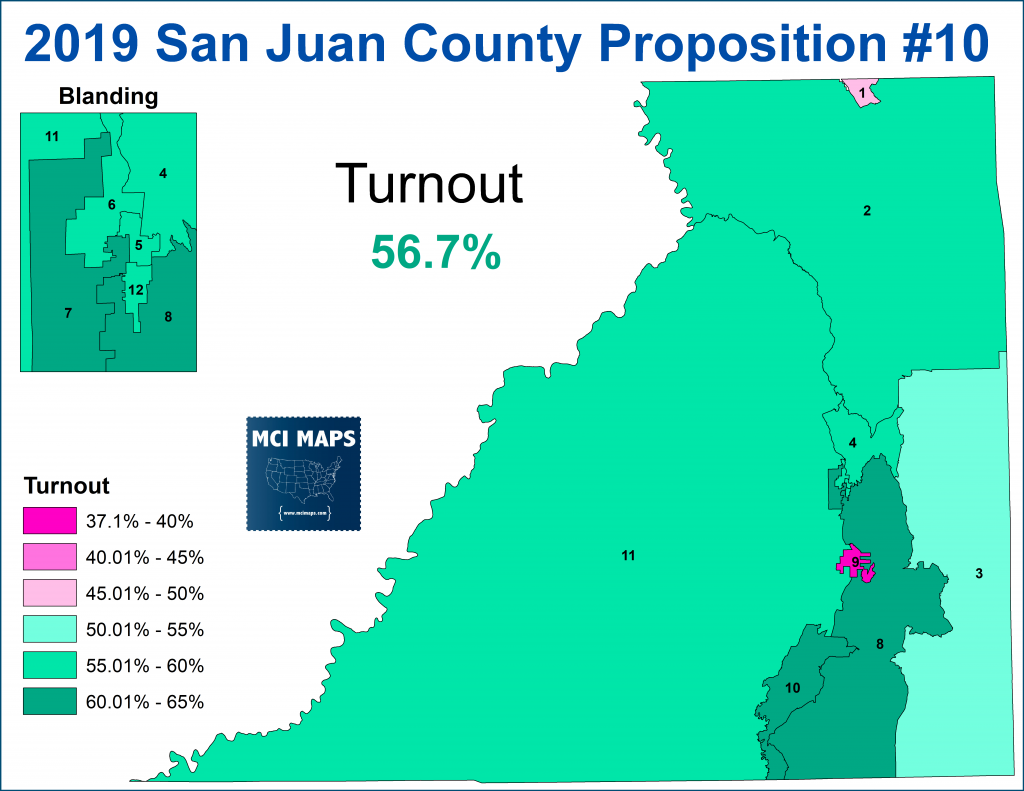

The biggest issue for Navajo voters in this referendum was turnout. Historically, the Navajo have had weaker turnout than their white counterparts – a product of poverty, lack of infrastructure, and the general isolation of the reservation from the rest of the county. For decades, the county was always weak on encouraging tribal participation, and as my previous article showed, pushed election changes that undermined Navajo voting. All of these factors, coupled with a sudden referendum in an off cycle – but the same day Monticello would hold its city elections – convinced me the Navajo could face a serious turnout deficit. However, that did not occur. The tribe and local Democratic party made a major push to inform Navajo voters about the referendum and plan for GOTV efforts on election day and with absentee ballots. The effort worked, as turnout was strong in the reservation – and generally even across the county.

Turnout around the reservation largely matched the northern, white precincts. Only a few precincts really stood out with bad turnout. Precinct 9: A small precinct covering White Mesa; and Precinct 1: covering Spanish Valley.

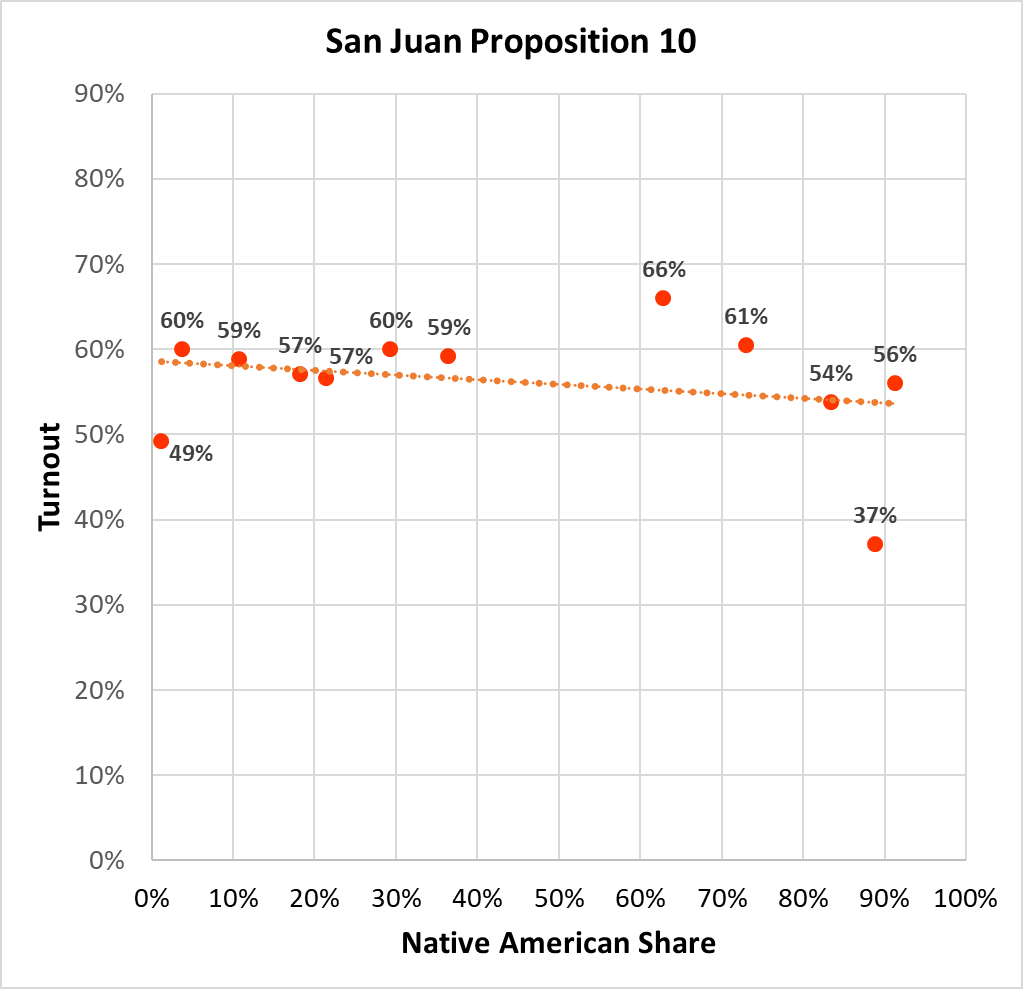

Looking at turnout compared to race, there is no statistically relevant rise or fall based on the precincts share of Navajo voters; a stunning shift from decades of past elections.

Turnout was nearly even across the commission districts as well. Heavy-white district 1 actually saw the weakest turnout!

For decades, despite a near-even population split, the white political establishment of San Juan was able to win countywide due to lopsided turnout dynamics. This was the first real example where the old establishment failed county-wide.

Conclusion

With the defeat, Mayor Lyman said he was done with the issue – saying the voters had spoken. However, history tells us this is unlikely to be wrapped up. 2020 won’t see many heated local races – as county clerk and county 2 aren’t up till 2022. There will be a race for County Assessor, and perhaps the Navajo will try and flex their muscles and field a candidate – time will tell.

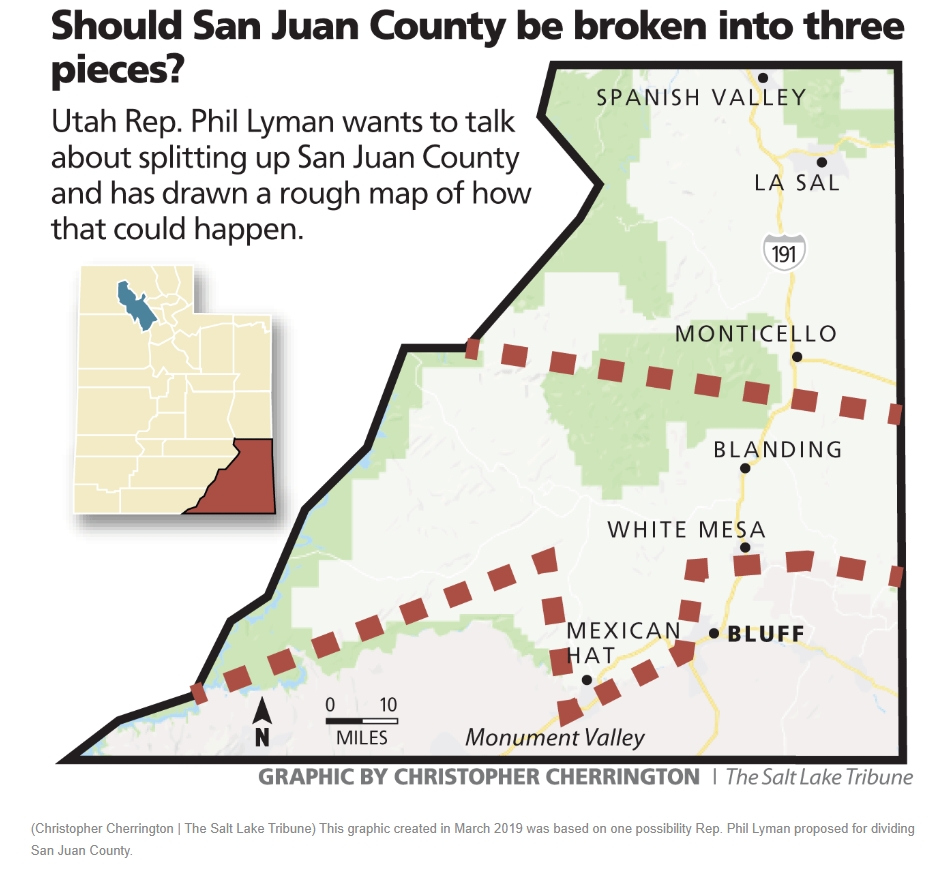

Additionally, a push to make it easier for counties to split is being debated in the legislature. Much of the push revolves around the mammoth Salt Lake County, but State Rep Phil Lyman, a former San Juan Commissioner, is also a supporter. Lyman actually discussed a general idea to split San Juan into 3. The map is from the Salt Lake Tribune.

The last time the issue came up, the bill was narrowed to apply to larger population counties. As one can imagine, most lawmakers in Utah probably don’t follow or care much about the issues of San Juan. However, with Lyman supporting splits, the issue cannot be considered dead.

San Juan has a long and tense history and the last few years have been no better. The victory in 2018 led to an attempt to overturn the results, which has now failed. How things move forward from here is not clear. But one thing is for sure, many of us will be watching.