Backstory

In December of 2016 I was in my car driving from Tallahassee, Florida to Arlington, Virginia for a much-needed vacation. I put on a podcast called “Reveal” and in the episode about voting, I heard the story of San Juan County Utah. I’m sure that for most folks, like myself, they never heard of San Juan County. It is county of only 15,000 people located in the southeast corner of Utah. It has gained much more attention in the last few months for being the site of the Bears Ears National Monument – a designation given by Obama, supported by the Navajo Tribe, opposed by white Utah conservative leaders, and who’s size was shrunk by Donald Trump.

San Juan has unique geography to it. Much of its land is open, controlled by the state or federal government. Its southern sector is part of the Navajo Nation reservation and its white residents largely reside in a few cities. Drive time across the county is upwards of 4 hours, much of it through open space.

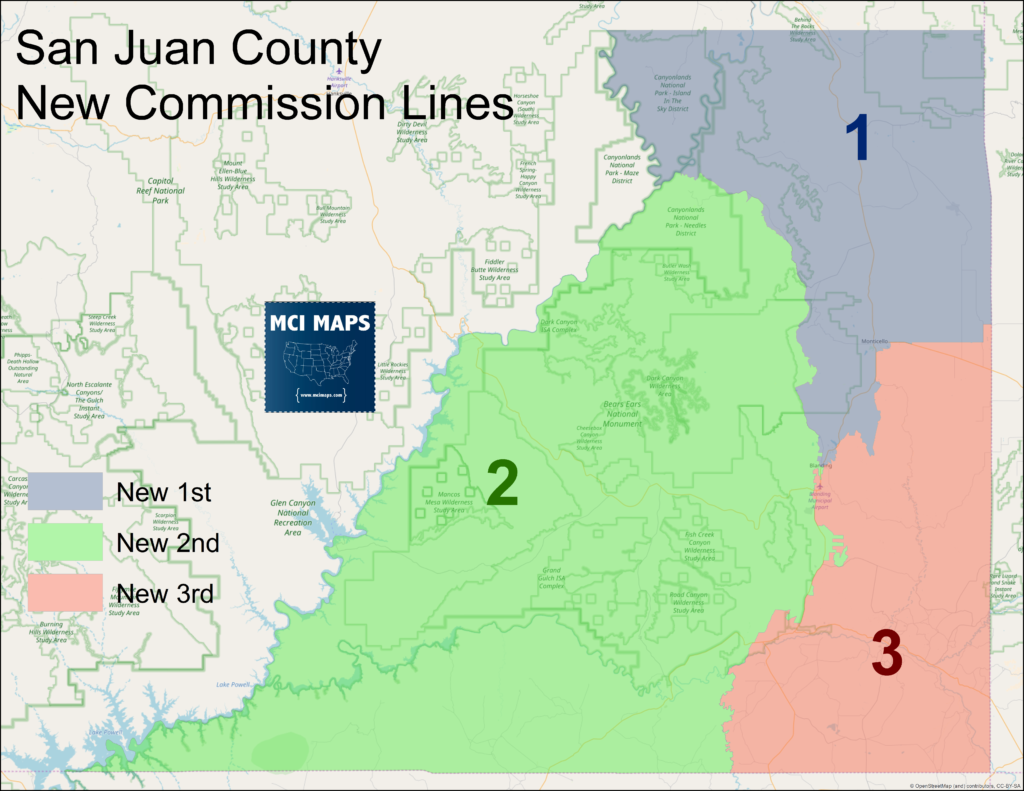

However, this article isn’t about bears ears or San Juan’s open spaces. Rather, it is about these county commission lines.

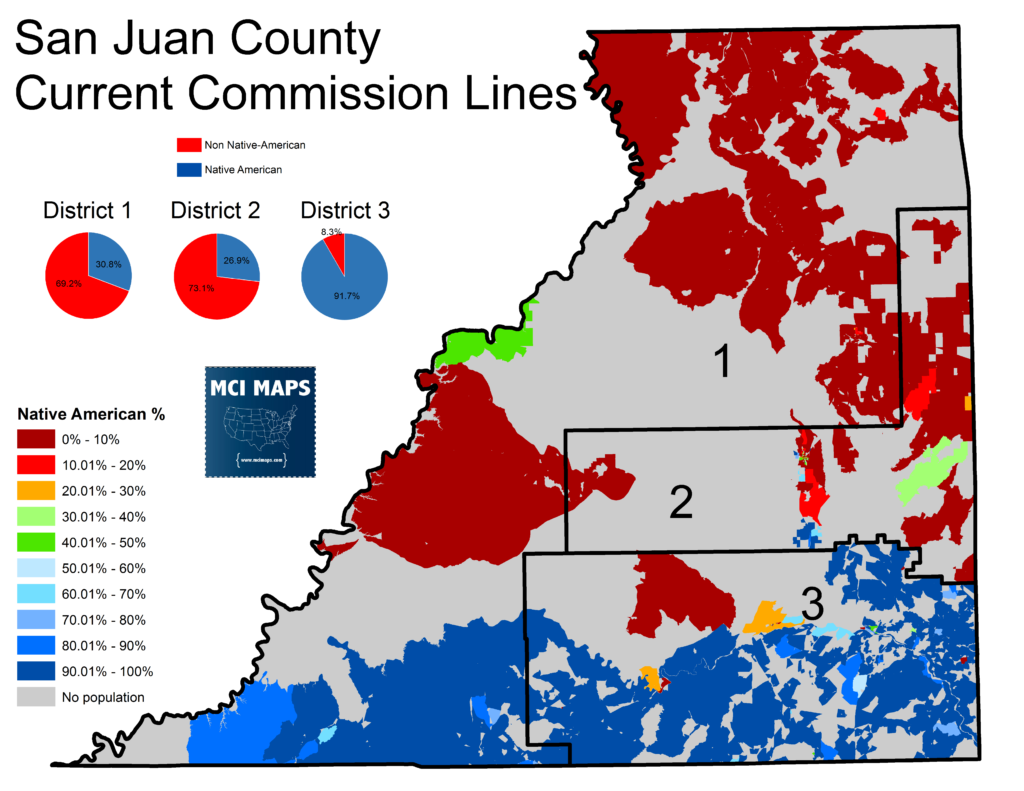

These lines, put into place after the 2010 census, have been struck down by a federal judge for violating the Voting Rights Act. In a county that is half Native American (almost entirely Navajo), these lines were designed to ensure one Navajo commissioner and two white commissioners. But before we understand how we got here, we need to take a look at the backstory of San Juan County.

Politics of San Juan County

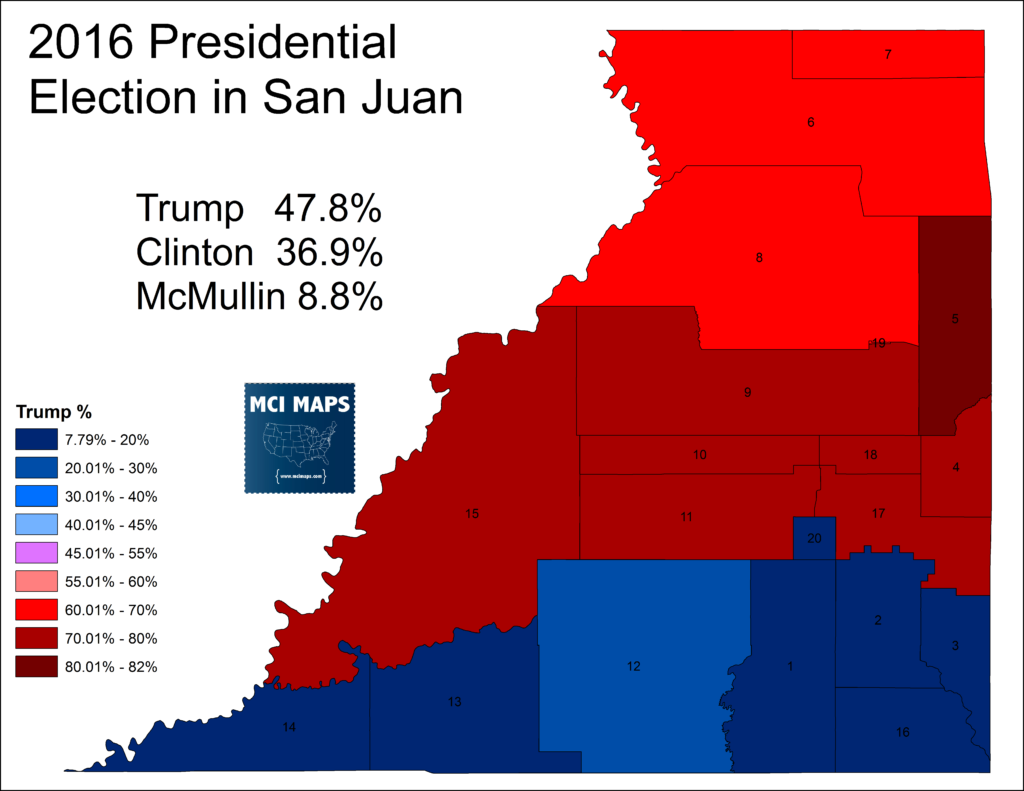

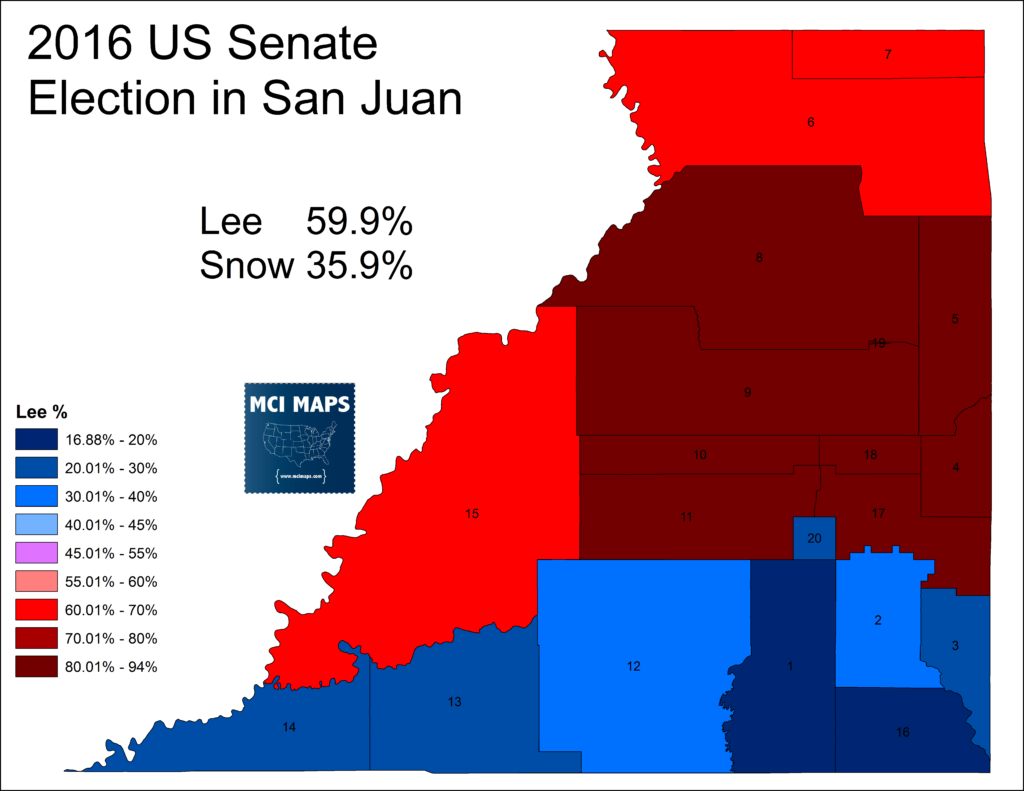

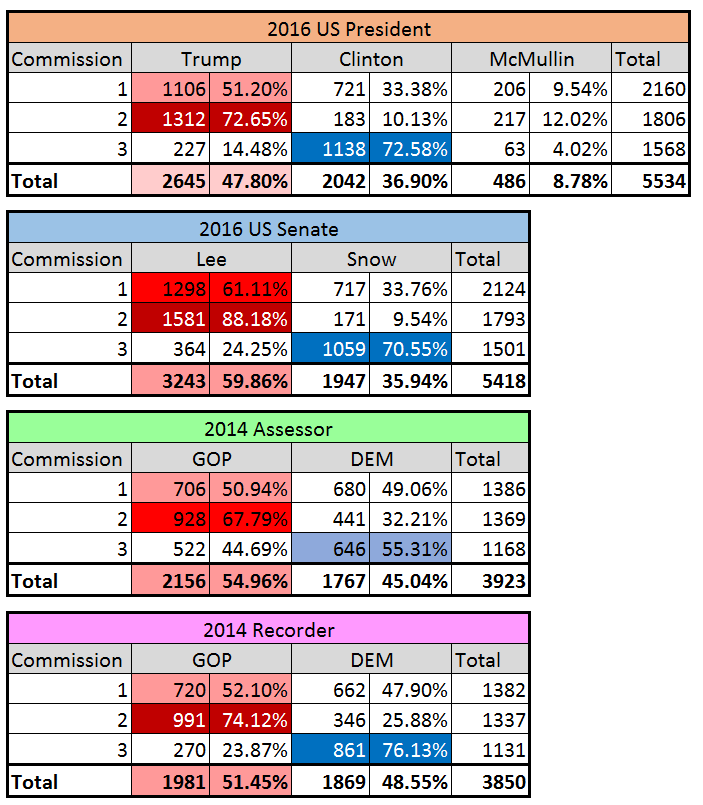

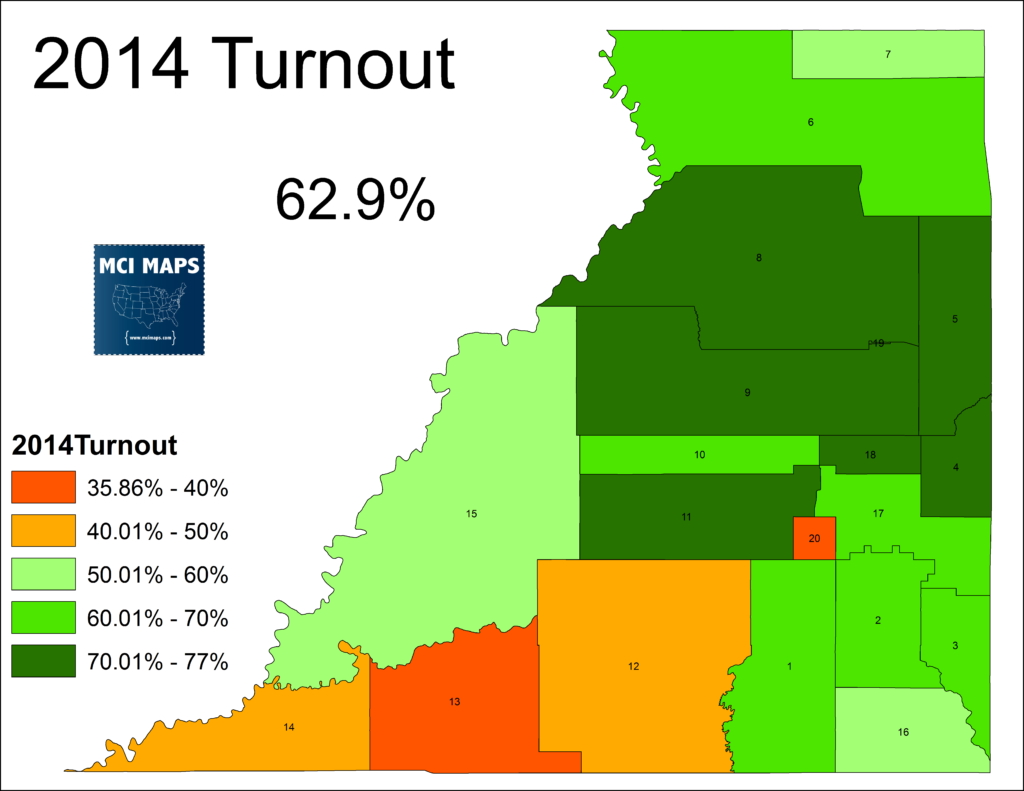

San Juan County is a reliably red county, though its is incredibly polarized in its voting. The Navajo reservation is overwhelmingly Democratic while the rest of the county, heavily white and Mormon, is solidly Republican. While the racial makeup of the county is nearly-even, lower Native American turnout leads to a county-wide electorate that is more white than its census or registration would indicate.

- Precincts making up the Navajo reservation are 46% of the census population and voter registration.

- However, the 2016 turnout only saw those precincts make up 41% of the total vote, and only 39% of the 2014 midterm vote.

Meanwhile, the county’s voting is heavily polarized on political and racial grounds. Whites tend to back top-of-ticket GOP candidates with 70% or more while the Navajo voters are over 70% for Democrats. The result is steady support for GOP candidates but always with modest margins. These political dynamics are not too dissimilar from the white/black dynamic in parts of the deep south.

The prime examples of the racially polarized voting is the 2016 US Senate and 2016 US Presidential elections. Both saw extremely polarized voting inside and outside the reservation.

Both elections saw the Democratic candidate shares coming from the reservation. The only deviation was the presence of Mormon candidate Evan McMullin, who took GOP votes from Trump outside the reservation.

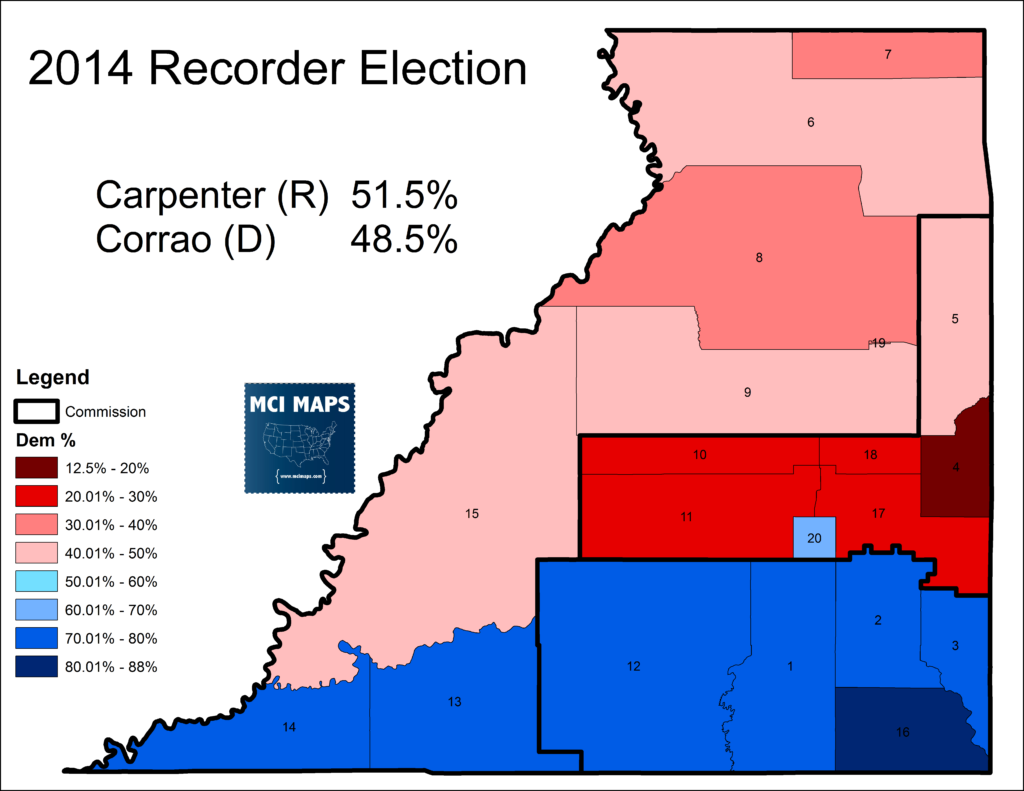

Some races have been closer. The closest race in recent memory was the 2014 race for County Recorder. Both candidates were white but the Democrat came within 1000 votes of taking the position. She did strong in the reservation and kept margins closer in northern precincts. However, the are around Blanding (middle of the county) is deep red.

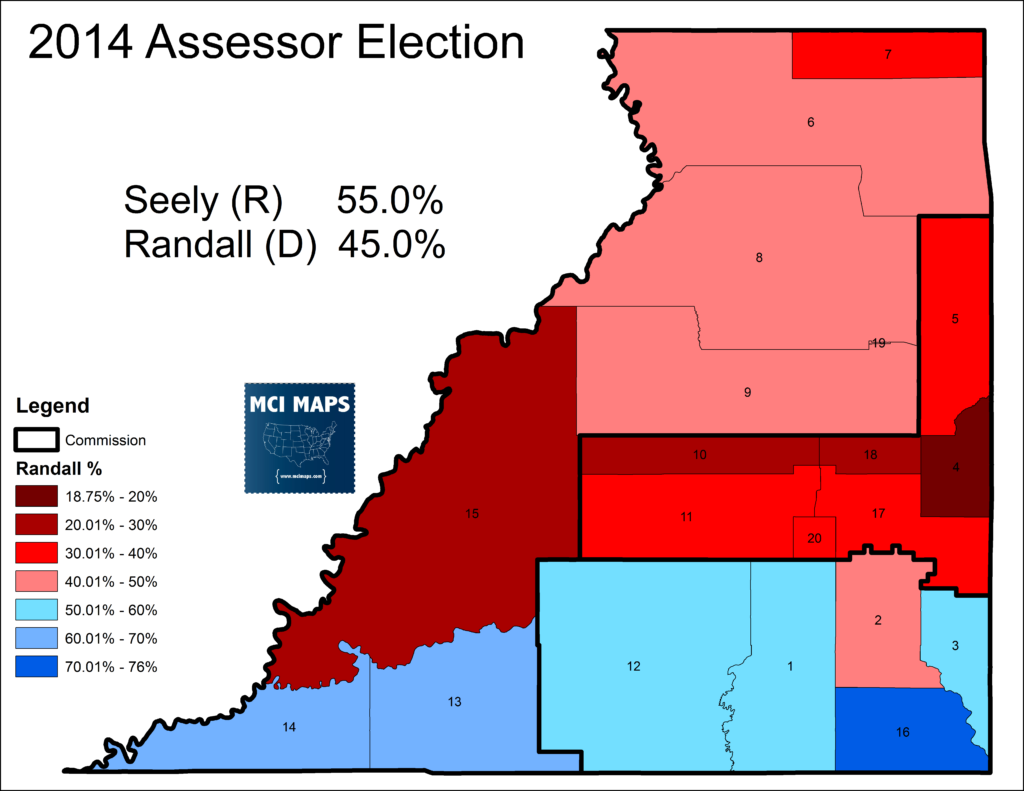

The Assessor race, held in 2014 as well, marked the strongest showing for a Republican in the reservation.

Since the 1980s, no Navajo Nation member has ever won county-wide election in the county. The commission districts vote totals are routinely 2-1 GOP vs DEM.

The 1st district can be seen as a bit more swingish. However, as I will show later, that swing is when the Democratic nominee is white, not when they are part of the Navajo tribe.

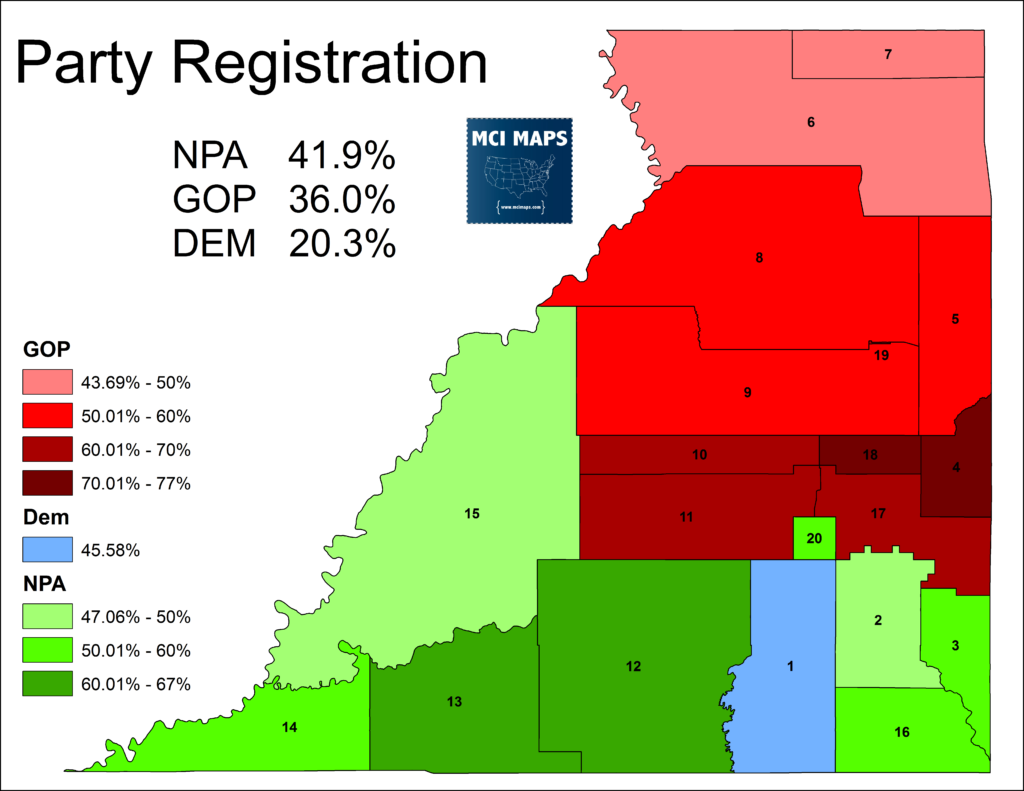

Registration-wise the county is more NPA than GOP. The NPA population is concentrated in the Navajo reservation, as is the Democratic registration. Republicans dominate outside the reservation.

These political leanings and divide are an important backstory. However, the historic tension and discrimination regarding the Navajo natives is the big reason the districts need redrawing.

San Juan County vs The Navajo Reservation

History of Tensions

San Juan has a contentious history when it comes to the Navajo reservation and representation on the county. San Juan originally elected its commissioners and school board members at-large. However, in 1986 the Justice Department successfully sued to have the county commission and school board districts elected to single-member districts. This allowed the creation of a seat within the Navajo reservation; ensuring at least one tribe member on the boards (ended up being 2 on the 5-member school board). Before this suit and after, the Navajo tribe was forced to sue the county over providing many services. Including, but not limited to….

- Ensure schools were built on the reservation

- Ensure utilities and power were supplied to the reservation

- Offer bilingual education options

- Provide school bus routes on the reservation

- Providing an ambulance housed on the reservation (the Navajo Nation finally provided it)

When the county was initially divided into single-member districts, the first Navajo commissioner was Mark Maryboy. Maryboy promptly found himself having to clash with the rest of the commission, especially conservative Calvin Black, over funding for the reservation and providing basic services. Efforts by the Navajo to run a slate of county-wide candidates in 1990 saw all fail to win.

Overall coverage of elections in San Juan show a hostility toward aiding the reservation from the rest of the county. Commission Chairman Bruce Adams has been adamant that the county has limited responsibilities regarding the reservation and that the Navajo Nation and Federal Government should fund those projects more.

Vote by Mail Shift

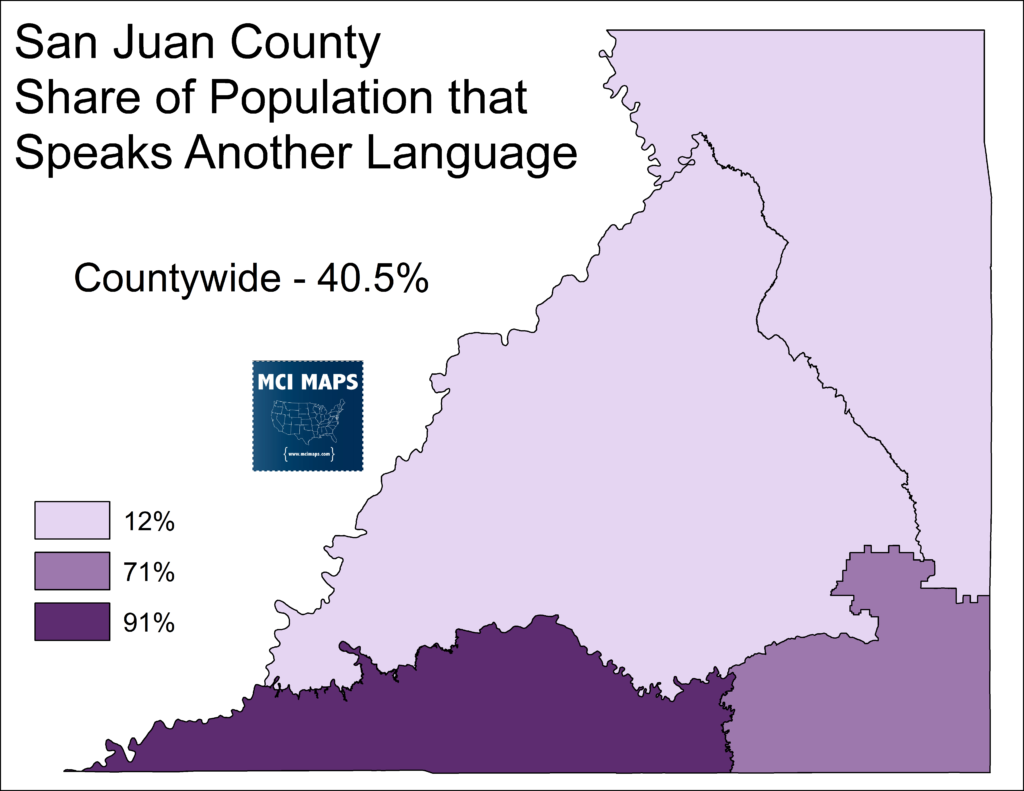

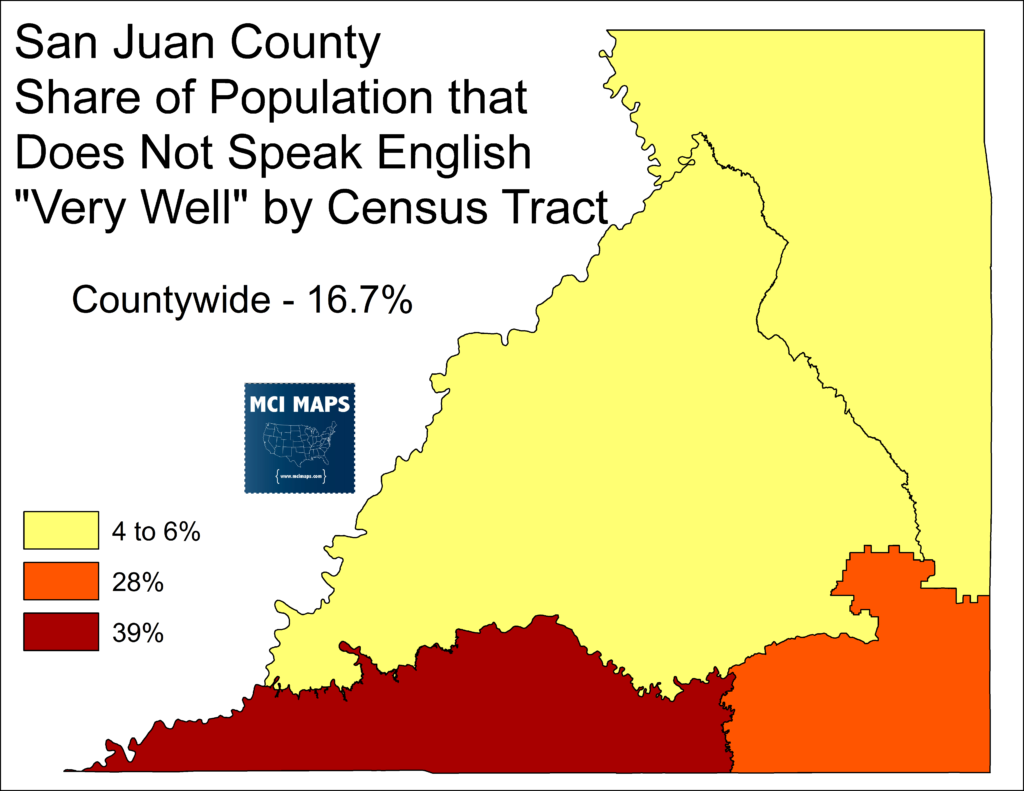

A prime example of county policies being taken without regard for the Navajo Reservation was the county’s 2014 move toward all-mail voting. The county decided to eliminate its 20 voter precincts and instead have all elections done by mail: similar to states like Washington and Oregon. The policy is normally a good one for voting: it can increase turnout and aids folks who cant always take the time to vote due to work. However, in San Juan, this change had many unforeseen, but predictable, problems.

The first was the issue of language. Older Navajo voters do not speak or read English well. Meanwhile, the Navajo language is oral-only. In past elections, the county would have translators at the pooling sites to aid the voters with their ballot. The move to all-mail voting eliminated those translators at each site.

The county only left one translator in the county – at the one remaining voting site – in Monticello, a heavily white city in the middle of the county. Voters would have been forced to drive to the location on election day for translation services. For voters around Red Mesa, it was over an hour drive. For those in Navajo Mountain, the only drive is 4 hours long. People in Navajo Mountain and the surrounding area would have to actually drive into Arizona to then make their way to Monticello.

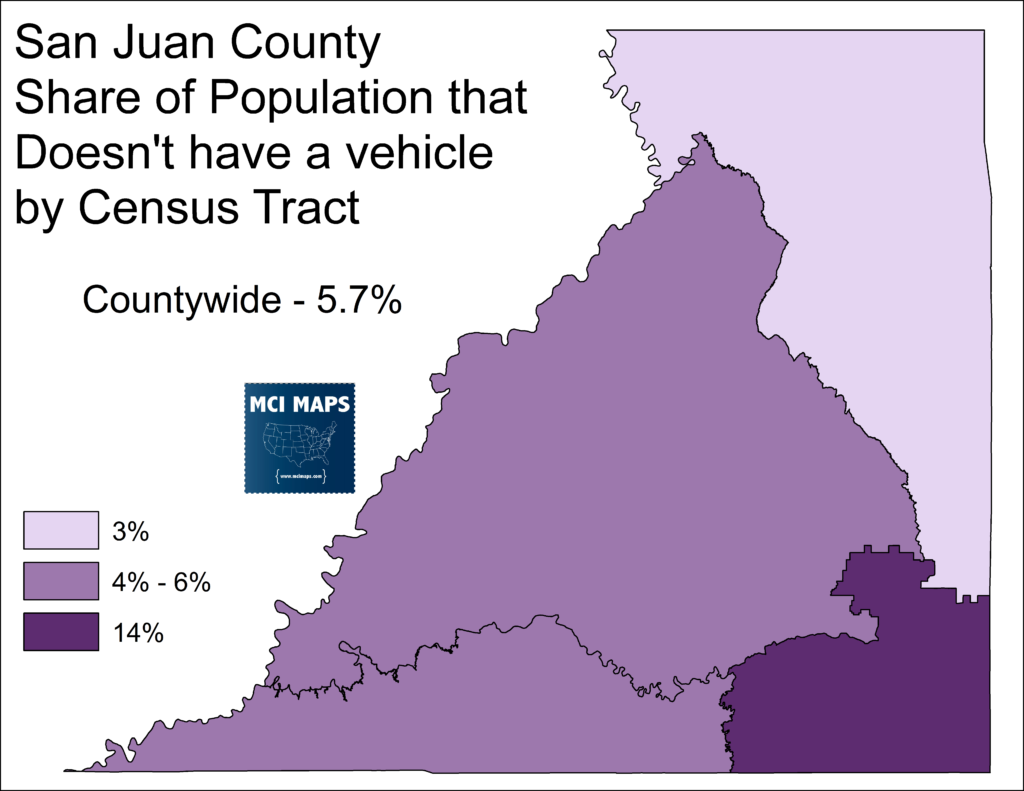

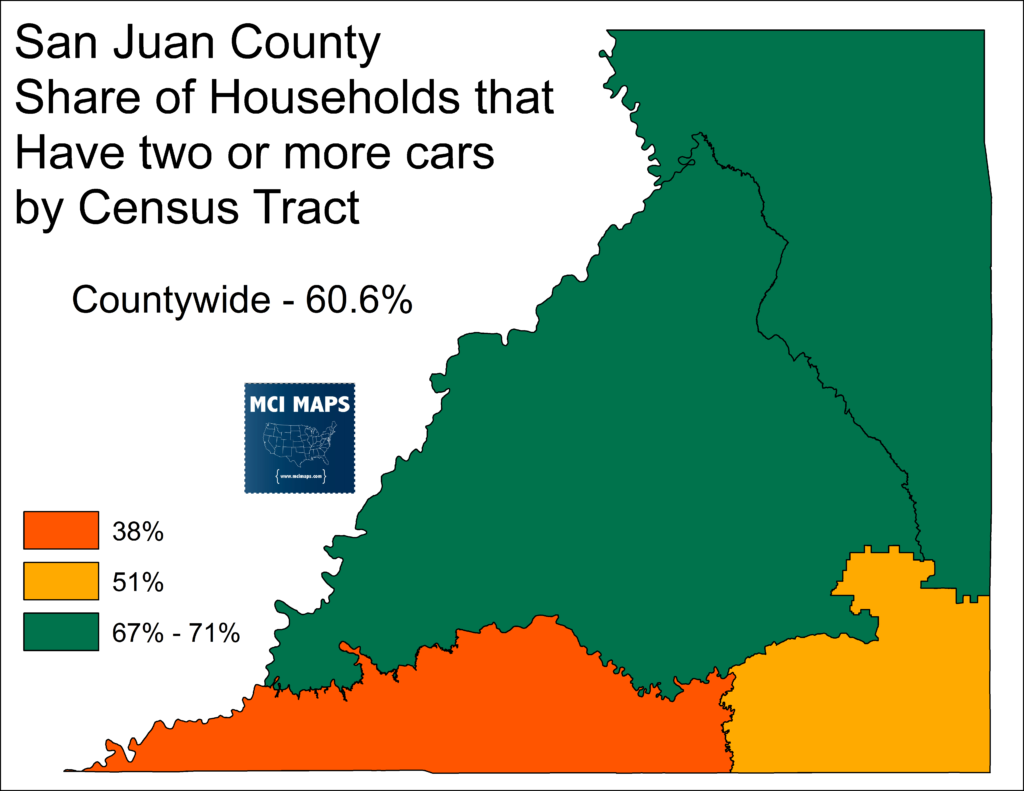

The issue of drive time was compounded by the reservation residents having fewer car options. Around 10% didn’t have cars and around half only have one per household (meaning the issue of picking kids up or going to work for one could impact the plan to drive to Monticello.)

For voters who do know English and could utilize the vote-by-mail process, the other issue was mailboxes. Mail delivery isn’t door-to-door in much of the county, both on and off of the reservation. While cities like Blanding or Monticello had PO Boxes right in the dense towns, the drive to PO Boxes or the post office for some reservation members could be an hour or more drive. Navajo Mountain residents often had PO Boxes in Arizona. The result was Navajo residents sometimes not checking their mail for weeks. In addition, studies of the mail system showed that the delivery time for mail in the reservation taking weeks, while the turn-around in the white cities was one or two days. This discrepancy was thanks to the rough terrain and spread out nature of the reservation and its effects on the US Postal service.

The entire vote by mail program was designed without consulting with the Navajo Reservation leaders. Many showed up to their normal election centers on election day to find out only then about the change. The county argued they used radio ads and sent reminders in the mail; but of course this missed many.

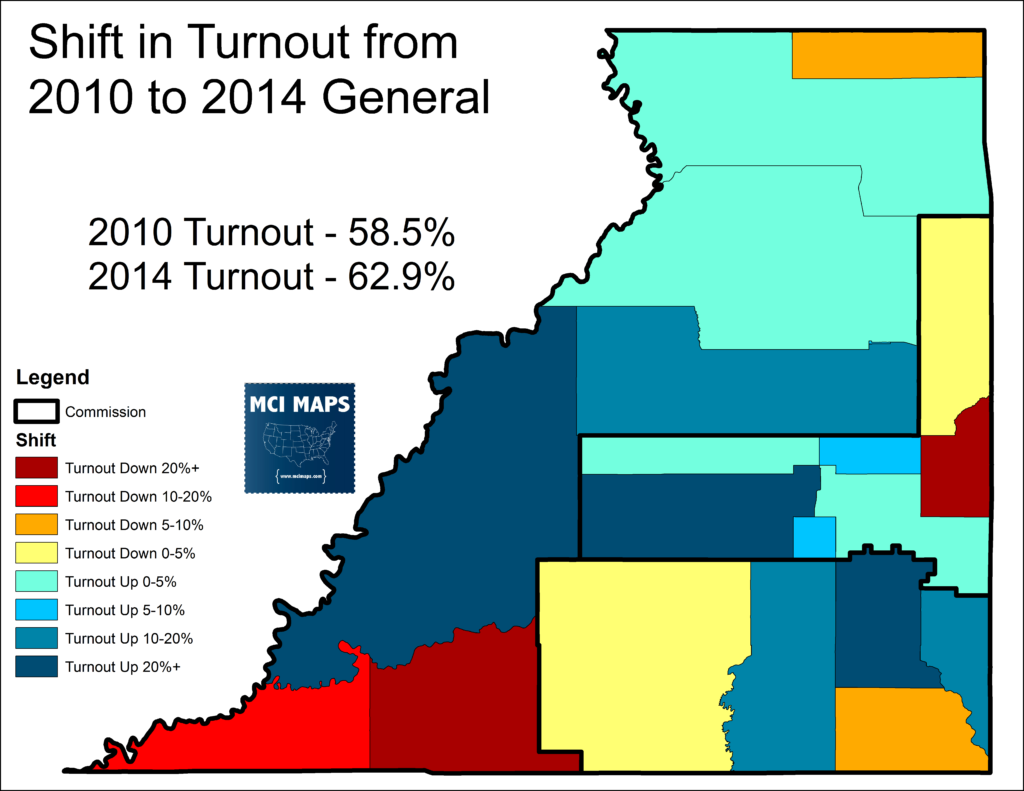

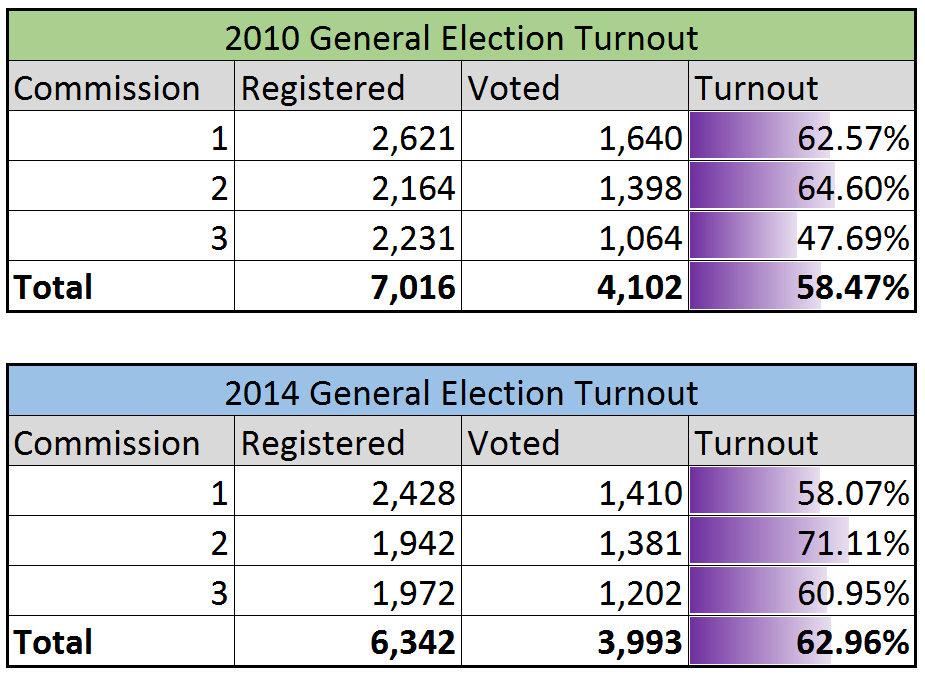

The results of this change were seen in 2014. Turnout was weaker in the reservation counties to the west (outside the third district). Turnout, compared to the 2010 midterms, did go up in a few precincts in the reservation, but collapsed in others around Navajo Mountain.

The county, defending the change, cited the improved turnout in the area around Montezuma Creek (in the east). However, as other experts pointed out, this ignored crucial points.

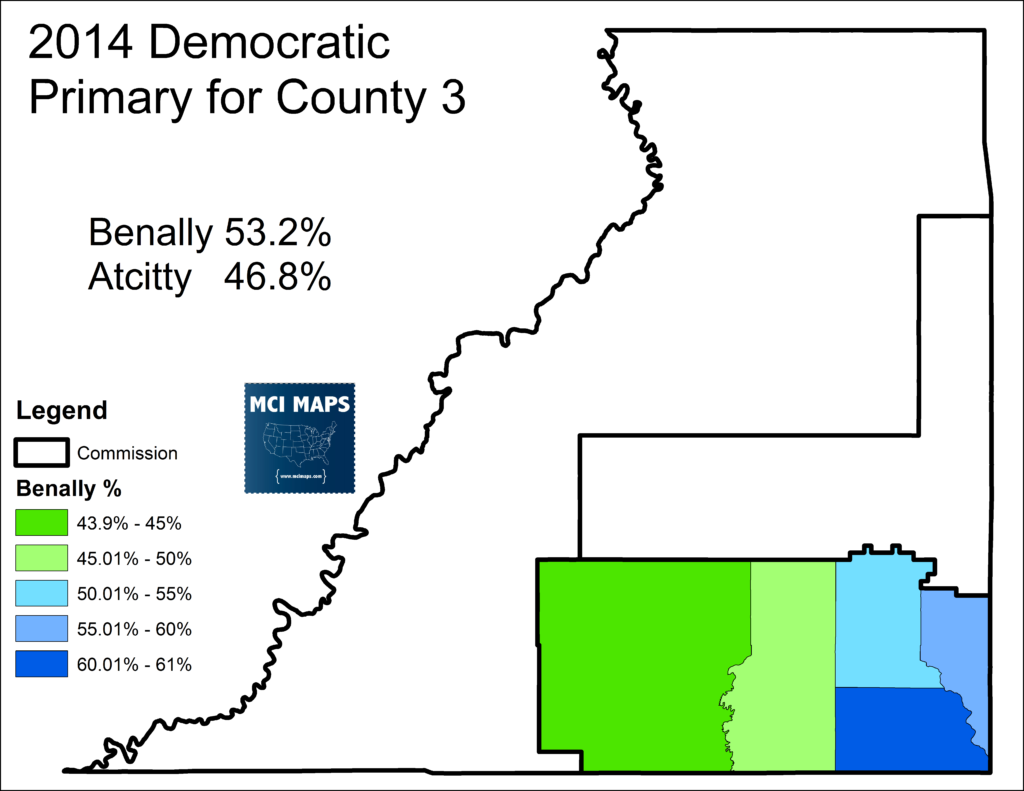

The biggest point was the presence of a major election in the third commission district, which covers Montezuma Creek and the eastern precincts. First up was a major Democratic Primary. Rebecca Benally won a close primary over Roger Atcitty for the Democratic nomination for the district. Incumbent Democrat, Ken Maryboy, part of the Maryboy family that has held the seat for all but a few years, was running for Navajo Nation President at the time.

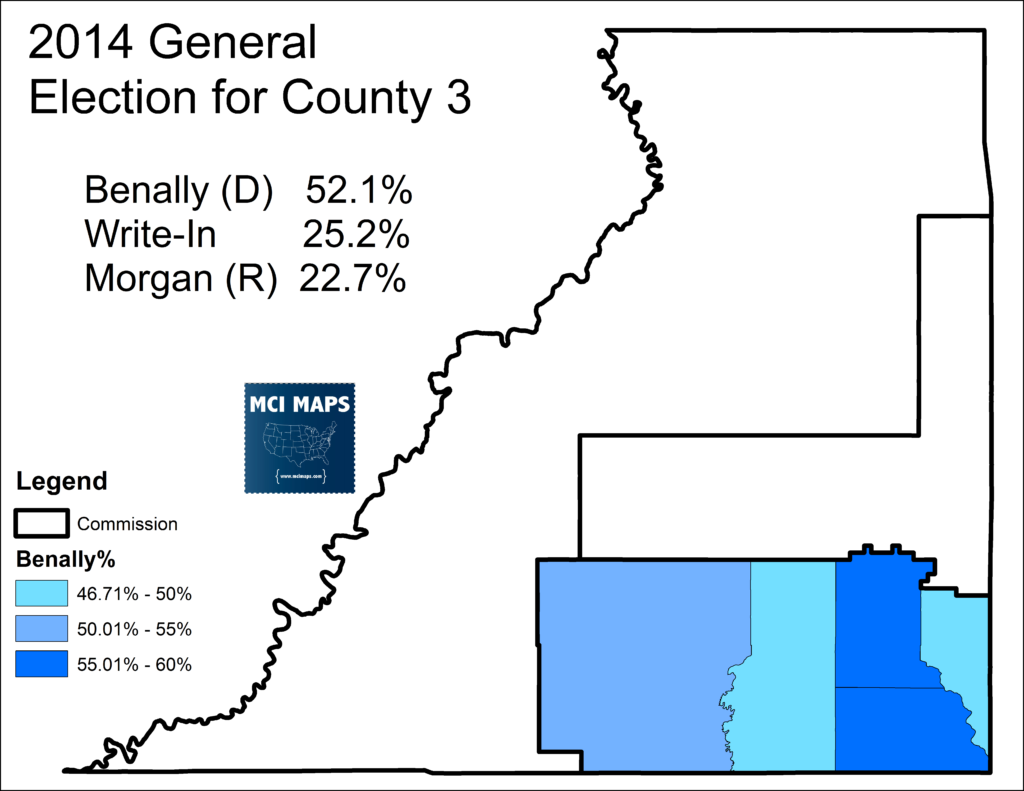

The general election then saw Maryboy run as a write-in for the general. In addition, Manuel Morgan, a former Democratic commissioner, opted to run as a Republican. This meant a tense three-way fight for the general election. Benally went on win the 3-way race.

All candidates were well-known figures in the community as well. The heavy campaigning, led by candidates who knew about the changes, no doubt aided in improving turnout in that region. In addition, these precincts were closer to Monticello and also had mail services with quicker turnaround than in western areas like Navajo Mountain.

The 13th and 14th precinct, representing the areas around Navajo Mountain, had no such competitive election. Hence those precincts saw a collapse in turnout. The collapse in those precincts was so high it drove turnout down in the 1st county commission district, despite its white areas rising in turnout.

Following the 2014 drama, the county agreed to bring back three election sites on the reservation, staffed with interpreters. This was the procedure for the 2016 elections, which still caused much confusion among Navajo voters about which sites to go to. A trial is underway over whether or not the county will be forced to restore all polling locations on the reservation. The changes in 2014 can easily be seen as violating the Voting Rights Act.

The 2017 special election for Utah’s 3rd district proceed with three reservation polling location. The Election Clerks website also included hotline numbers for Navajo voters to call and a recording of the ballot in Navajo.

The vote by mail drama is an important example of the disconnect between the Navajo Reservation and the rest of the county government. The all-mail voting was organized without input from Navajo leaders or frankly, care for their concerns. The tone of the county’s counter-claim against the Navajo in the lawsuit over this issue also highlight the hostility that exists. The county argued the suit was in bad faith, ignoring the obvious problems their proposal had caused, and made the lawsuit out to be political. The counter-claim argued that Benally’s win was thanks to the vote-by-mail system; breaking a chain of control away from Morgan and the Maryboy family (who have controlled the district since its creation). The county argued the Maryboys have traditionally ensured victory by handing out food at polling sites. This claim ignored Ken Maryboy was busy running for another office at the time Benally won, something that had nothing to do with the by-mail system. In addition, the claim, which is hard to quantify or prove, seeks to dismiss the real issues the mail system created and instead reduce the suit to political theater. The judge dismissed the county’s county-claim and the trial is moving forward. The opinion can be read in full.

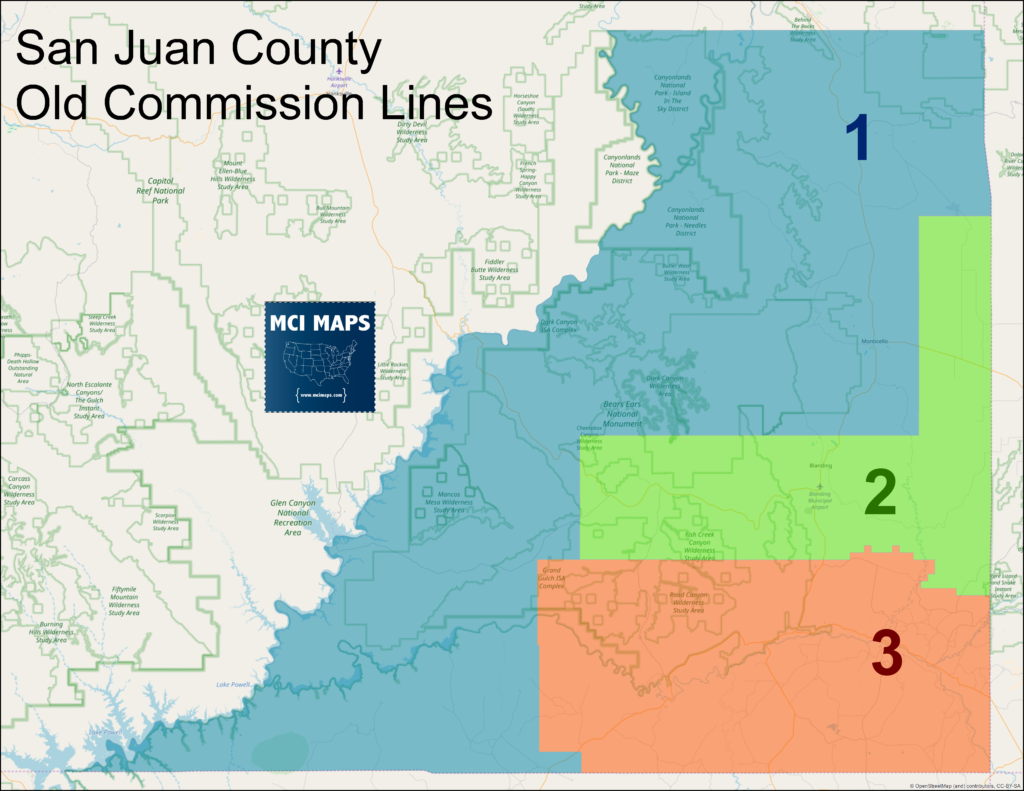

San Juan’s Redistricting Saga

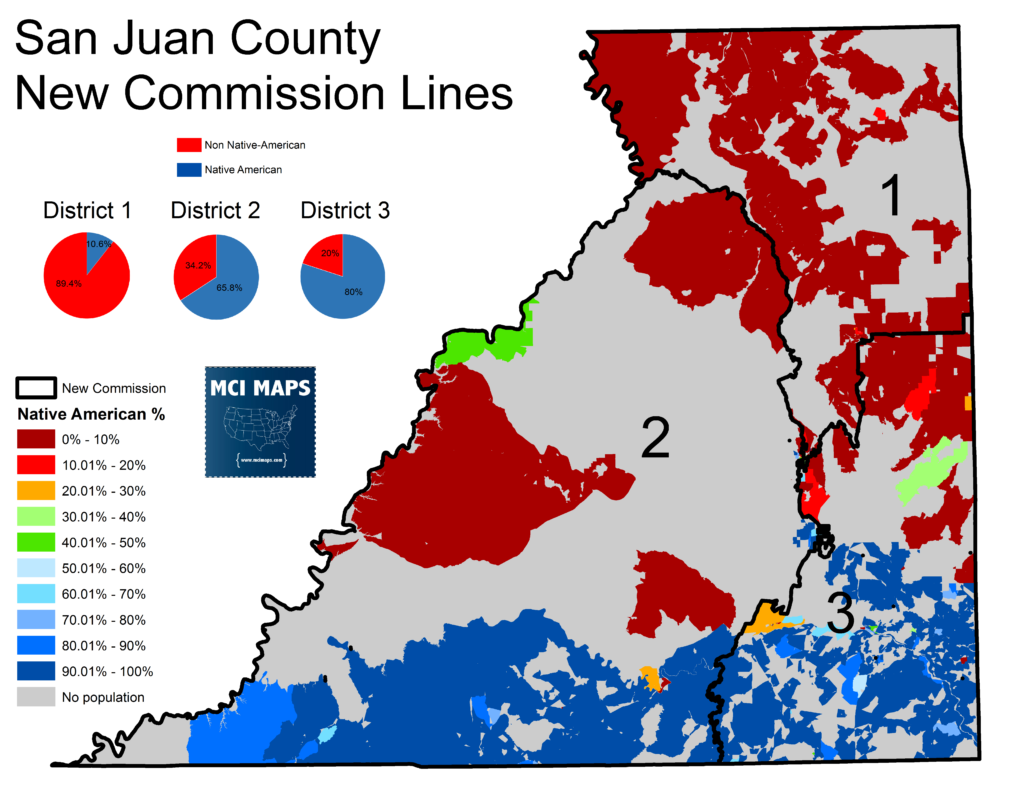

The general hostility between the tribe and non-tribe portions of the county mean representation on the commission and school board is important. While the push for single-member districts finally led seats at the table, votes on the boards have been routinely along racial, and hence partisan, lines. The current lines on the county commission are designed to have one Navajo seat and two white seats. The 3rd district on the commission is over 90% Navajo, while the 1st and 2nd seats are solidly white.

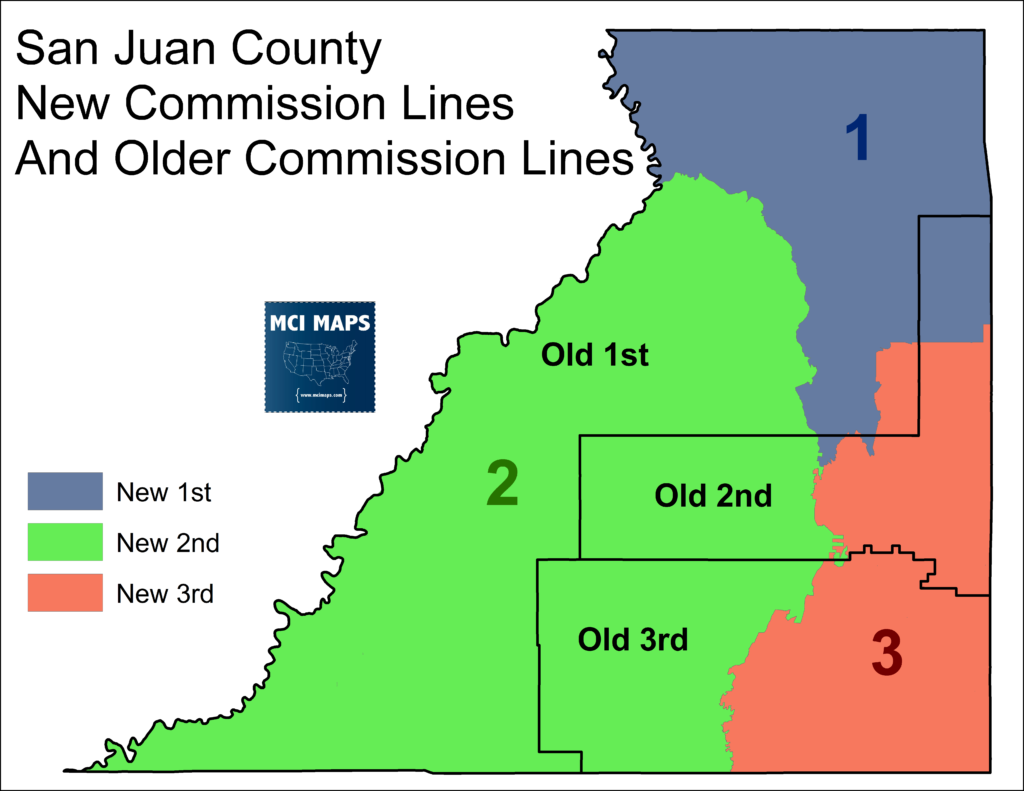

The Navajo Nation sued the county, arguing the districts were racially gerrymandered to pack Native Americans in the 3rd district. The federal judge agreed, and struck down the districts. Judge Shelby sited how the 3rd districts borders never changed and the county’s justification was purely on racial grounds, at the expense of all other redistricting principles. The 1st district was specifically single-out due for connecting the southwest and far north ends of the district. No roads connect those regions and they share no similar interests.

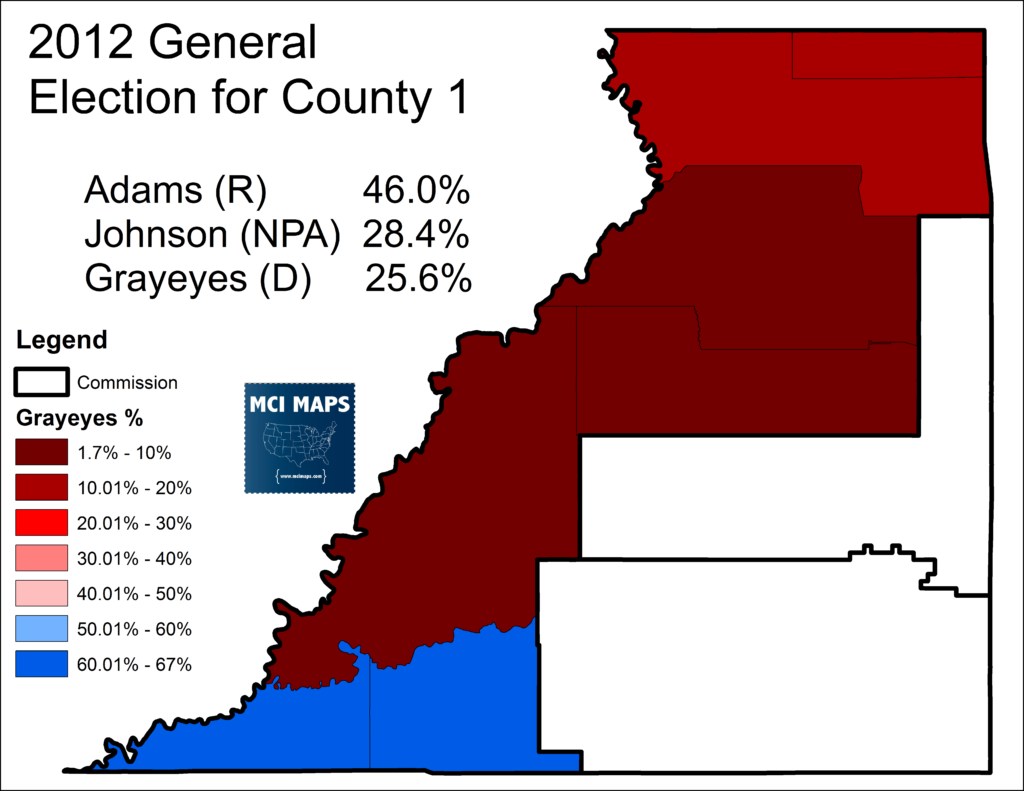

The issues with the 1st district can be seen in the 2012 General Election for the seat. Incumbent Commissioner Bruce Adams faced challengers from Willie Grayeyes of Navajo Mountain and an NPA, former GOP Clerk, Gail Johnson. While Republicans worried about a right-wing split, the district was too Republican for it to matter. Adams won easily. The map below shows Grayeyes support by precinct.

Outside the reservation, Grayeyes got only 7.5% of the vote. This type of racially polarized voting is the exact time of thing the VRA looks at. As the political history section showed, white Democrats have done much better outside the reservation.

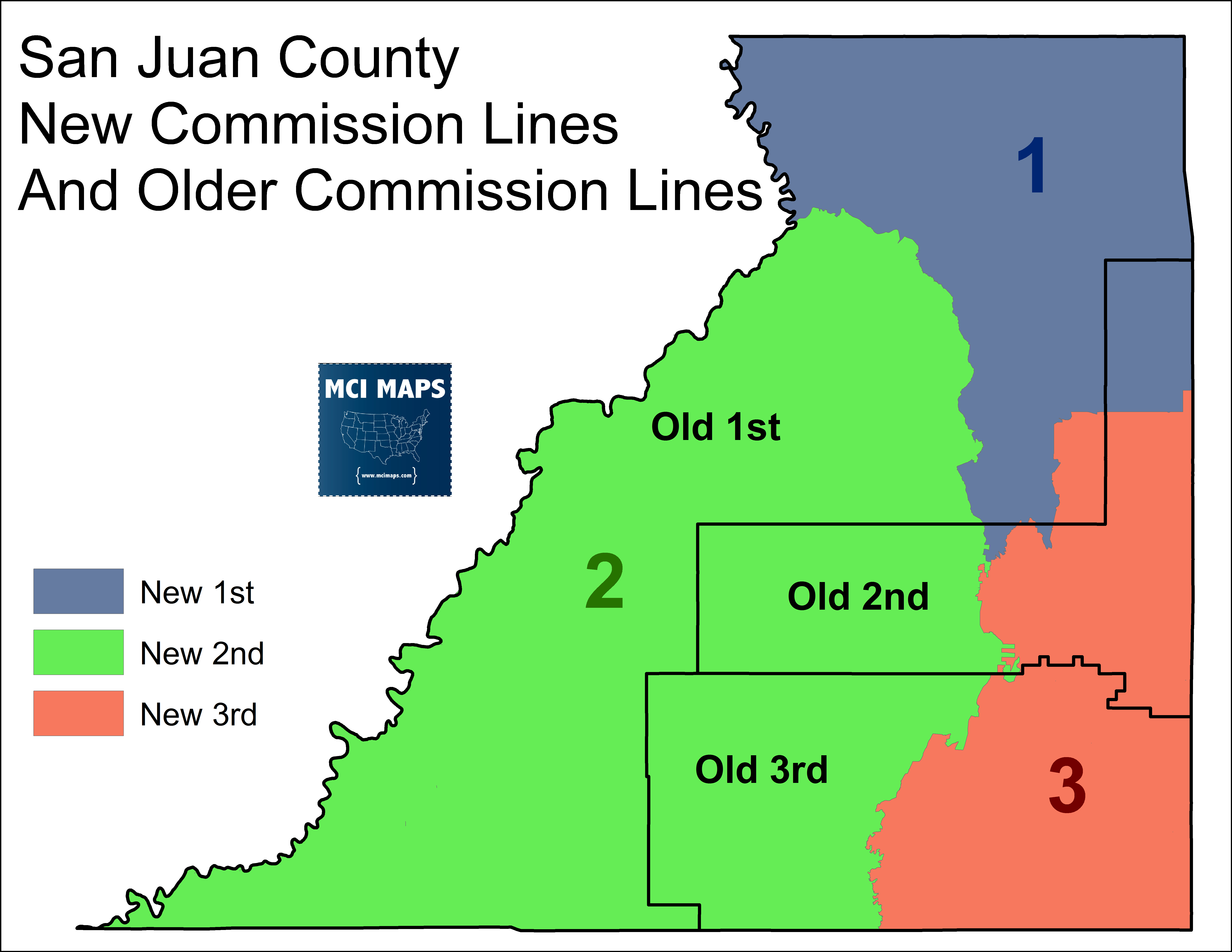

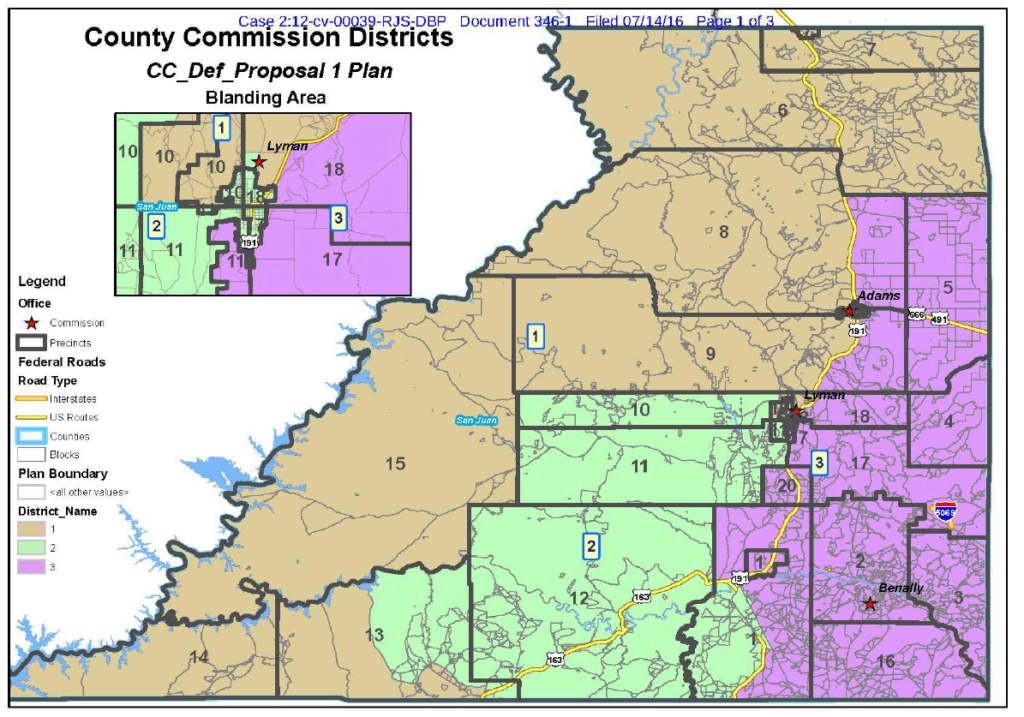

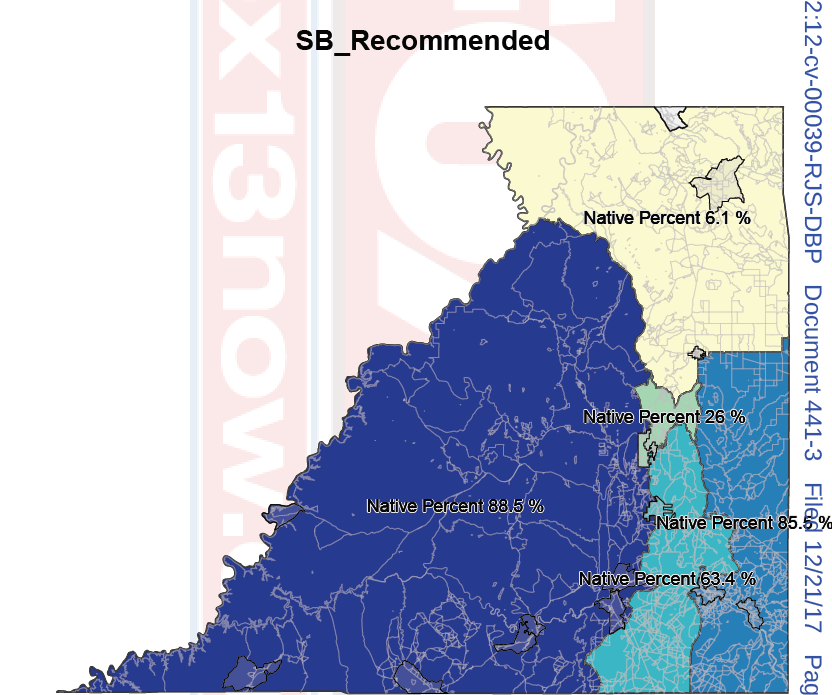

The judge ordered new districts be drawn. The county’s proposal in 2017 was rejected by the judge. The plan is below.

The plan’s racial makeup made the 3rd district 78% Native American and the 2nd was split between whites and Native Americans.

In his decision rejecting the map, Judge Shelby pointed out that county admitted race was the primary consideration in drawing the districts at the expense of other basic redistricting principles (like compactness and using natural and administrative boundaries). Another point against the proposal was the Native Americans in the 14th and 13th precinct (on the southwest) were put in the 1st, hence splitting the reservation three ways.

A special master was assigned by the judge to draw new districts while hearing input from both sides. Judge Shelby subsequently adopted the special masters’ proposal on December 22nd, 2017.

The new commission lines were drawn to balance population, political boundaries where feasible, and natural boundaries. The map has two Native American districts. the 2nd is now 65% Native Americans (63% Voting Age Population Native). It was argued that a higher native population was needed due to lower native turnout overall. While many reporting on the developments mis-characterized the new map has having 2 likely Navajo commissioners, the reality is the 2nd is definitely a swing seat. Most importantly, the districts were designed with race somewhat in mind but not with it being a predominant factor. The split of the reservation is based of natural boundaries (also used by the Navajo Nation districts). The resulting Native-American 2nd district is a natural byproduct of not packing as much of the reservation into one seat.

The new map will create a better balance on the commission by ensuring the 2nd district representative will need to be concerned about residents both on and off the reservation. Otherwise, electoral consequences are much more likely.

How the new lines compare to the old lines can be seen below.

The new school board districts, which used to be 2 Navajo and 3 white seats, were also approved. The new borders created a similar balanced racial approach while balancing political and geographic boundaries at the same time.

The county is pledging to appeal the ruling. Among their claims, they say the new map will cause whites to be discriminated against by the Navajo majority. If that sounds tone def and completely hypocritical, you are not wrong. Judge Shelby as routinely dismissed any claims that whites will be discriminated against and has rather pointed out the history of discrimination by whites as proof of needed changes to the districts. Another amazing claim is the county wanted new districts to conform to current precinct boundaries – a request the judge flatly denied, as precinct boundaries are not fixed administrative borders.

There will be appeals but with any luck the new maps will be implemented for the 2018 midterm elections.

Conclusion

When we talk about issues around redistricting and racial gerrymandering, we are largely thinking of the lines for Congress or State Legislature. However, what the tale of San Juan County shows is that there is a just as many issues with the lines at a local level. San Juan’s case turns out to be much more insidious than other local governments. The historic tension the county leaders have held and still hold toward the reservation and their requests come off incredibly mean-spirited in the research. A general sense that white San Juan would desire the reservation not even be part of their county emanates from the articles on the county government debates. Meanwhile, the Navajo, who make up 50% of the county, have been relegated to one seat for decades thanks to racial packing. One can hope that new maps will restore some proper balance to how the county government relates with its residents.