As states work to wrap up their redistricting maps for the legislatures and Congress, local maps are in the process of being finalized right along with them. Redistricting for city or county councils rarely gets major attention outside of the local communities. However, many municipalities have struggles and fights that mirror some of the heated Congressional line debates we all know well. Taking a break from larger redistricting fights, I want to talk about a small county of San Juan, Utah. Sitting on the northern end of the Navajo Nation, this majority-Native county has been subject to some heated redistricting fights.

Background

Those of you who have followed my writings for years will know I’m fixated on San Juan County, Utah. In 2016, I became aware of the struggles of the Native American population that makes up a slim majority of the county. The Native, largely Navajo, people were engaged in a battle of voting access and redistricting. I began to research and eventually wrote two articles on San Juan. The first was a detailed breakdown of San Juan’s political history and the struggle between the Navajo and White residents. I highly recommend that reading as background; but I will offer a short summary below.

Geography, Race, and the Navajo Nation

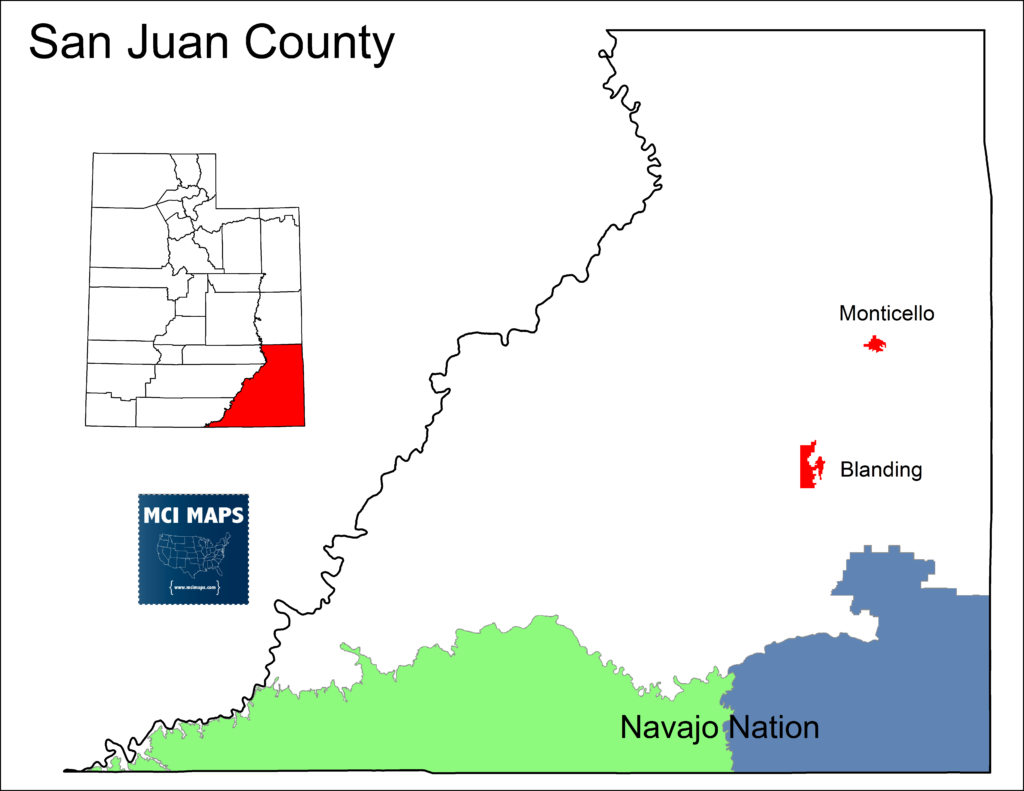

San Juan County, as mentioned, is narrowly majority Native American. The county only has around 15,000 residents – spread out in a very, very, veryyyy rural county. Like much of the west, a good deal of land is protected and not populated. San Juan’s largest cities are Monticello and Blanding. The Navajo Nation reservation sits on the southern end.

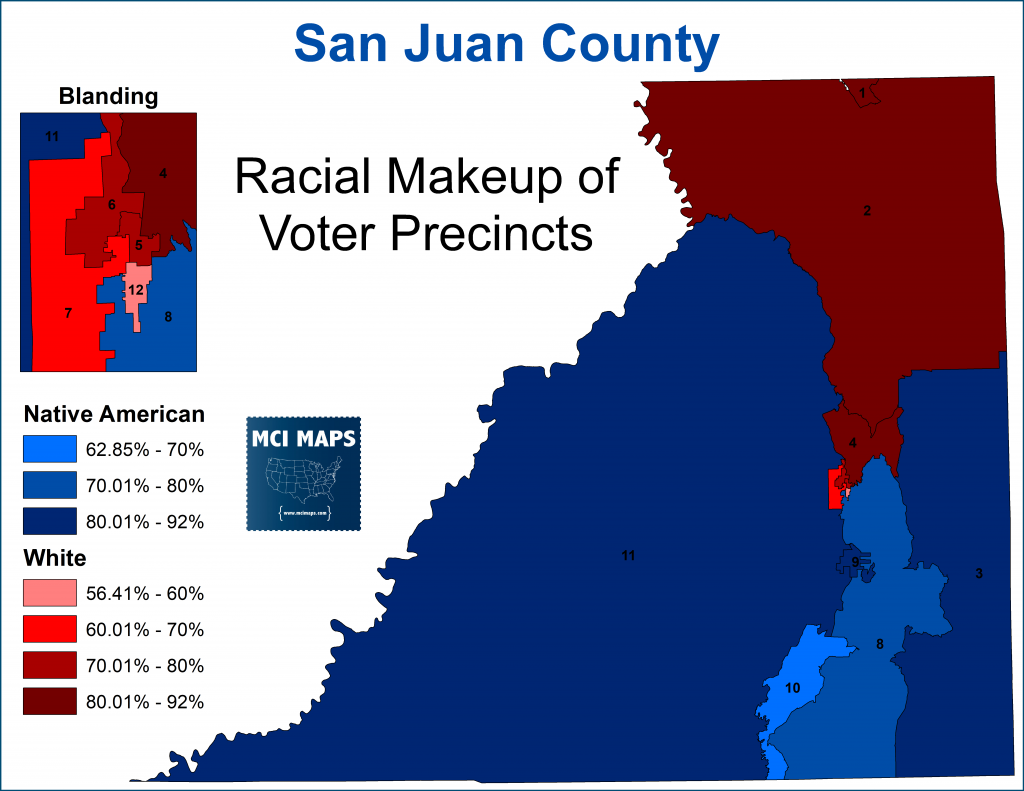

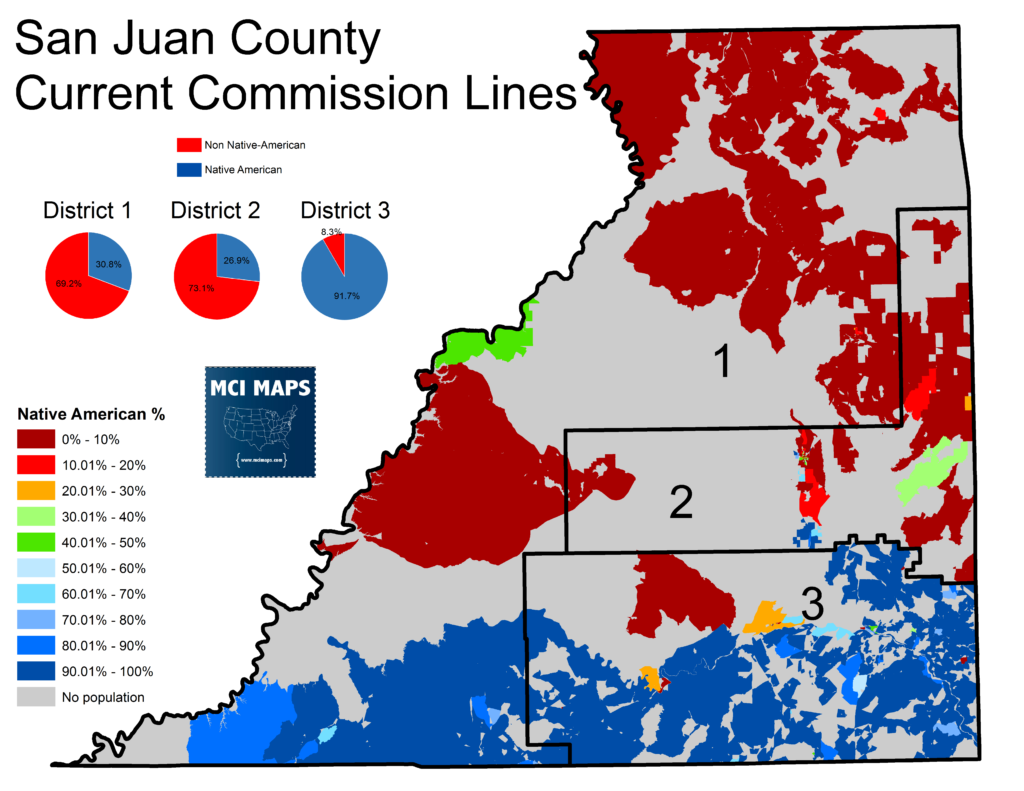

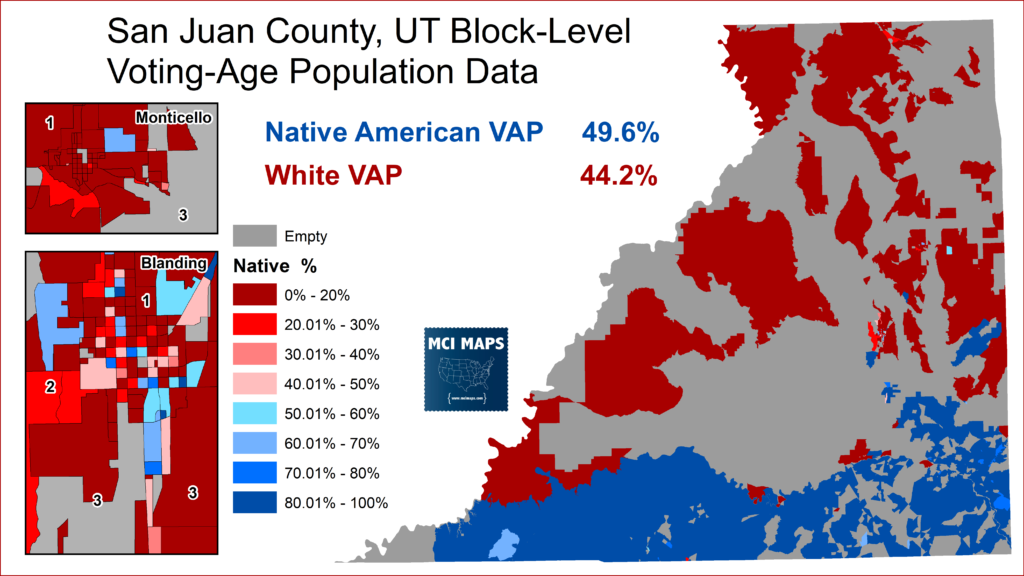

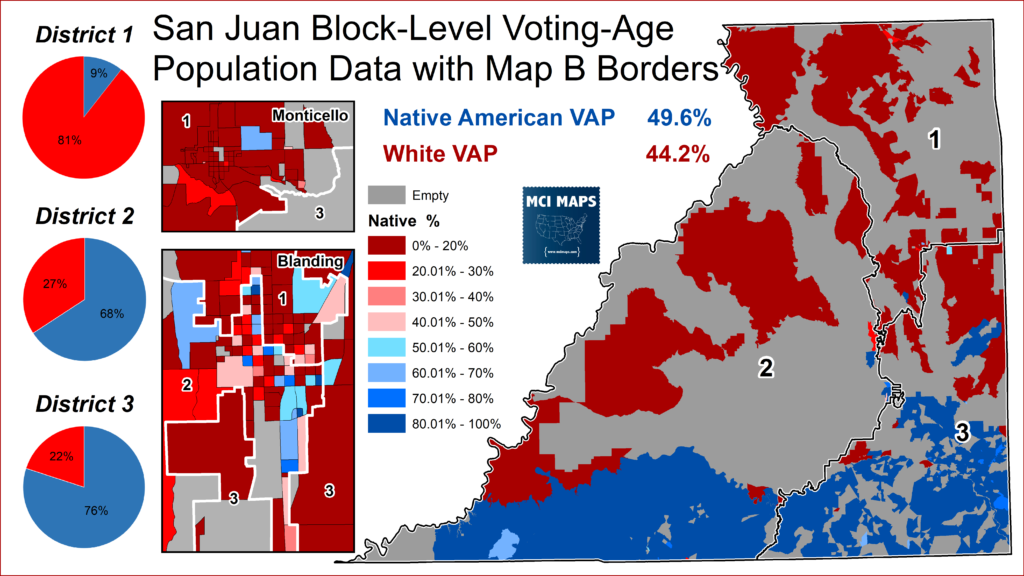

The latest census figures give Native Americans just under 50% of the voting-age population. As the block-level map below highlights, a large number of census blocks are empty. The population is also heavily segregated. Blanding is the most integrated area in the county.

Overall San Juan is Native in the south and white in the North. Most precincts are heavily white or heavily Native.

This segregation led to a great deal of discrimination. As I laid out in my first article, there was a long history of the white-controlled Government not wanting to offer services to the reservation. A tug-of-war between San Juan County, the Navajo Nation, and State of Utah only led to residents of the reservation not getting services they needed. Commissioner Ken Maryboy, a member of the Navajo Nation, summed the situation up below.

The tension only grew in the 2010s.

Court Maps Ordered

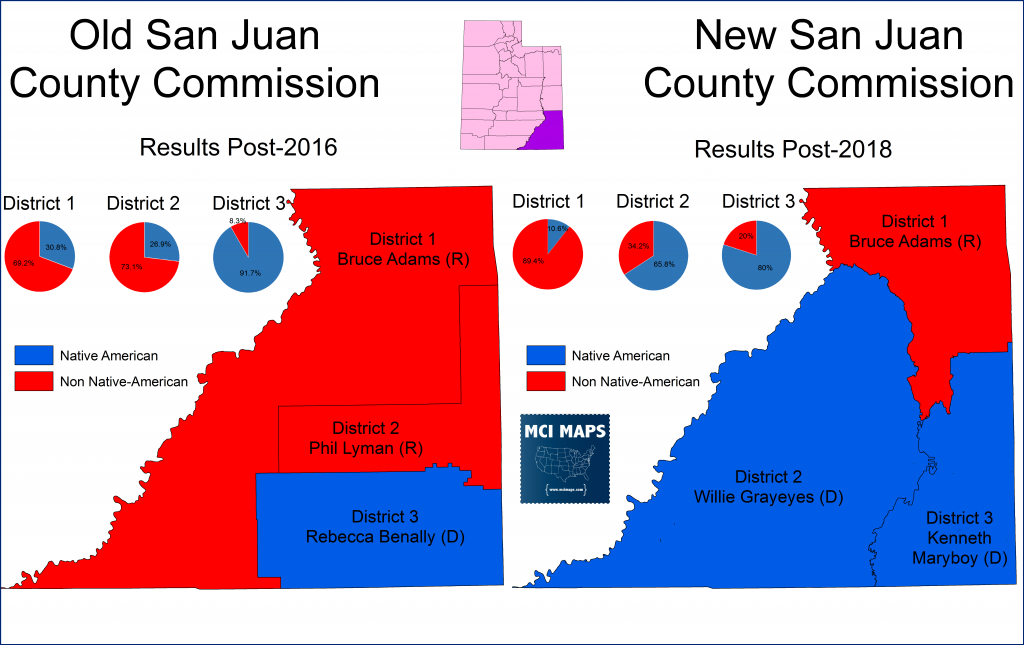

In 2012, the Navajo residents of San Juan asked the commission to undergo redistricting. The 3-member commission used to be elected at-large. A 1984 court case moved the county to single-member districts in order to give the Navajo a chance to elect candidates of their choice. Despite the county being almost equally Native American and White, the stronger white turnout and racially polarized voting ensured white candidates always won. The 1984 court-imposed lines created a heavily Native American district located in the reservation.

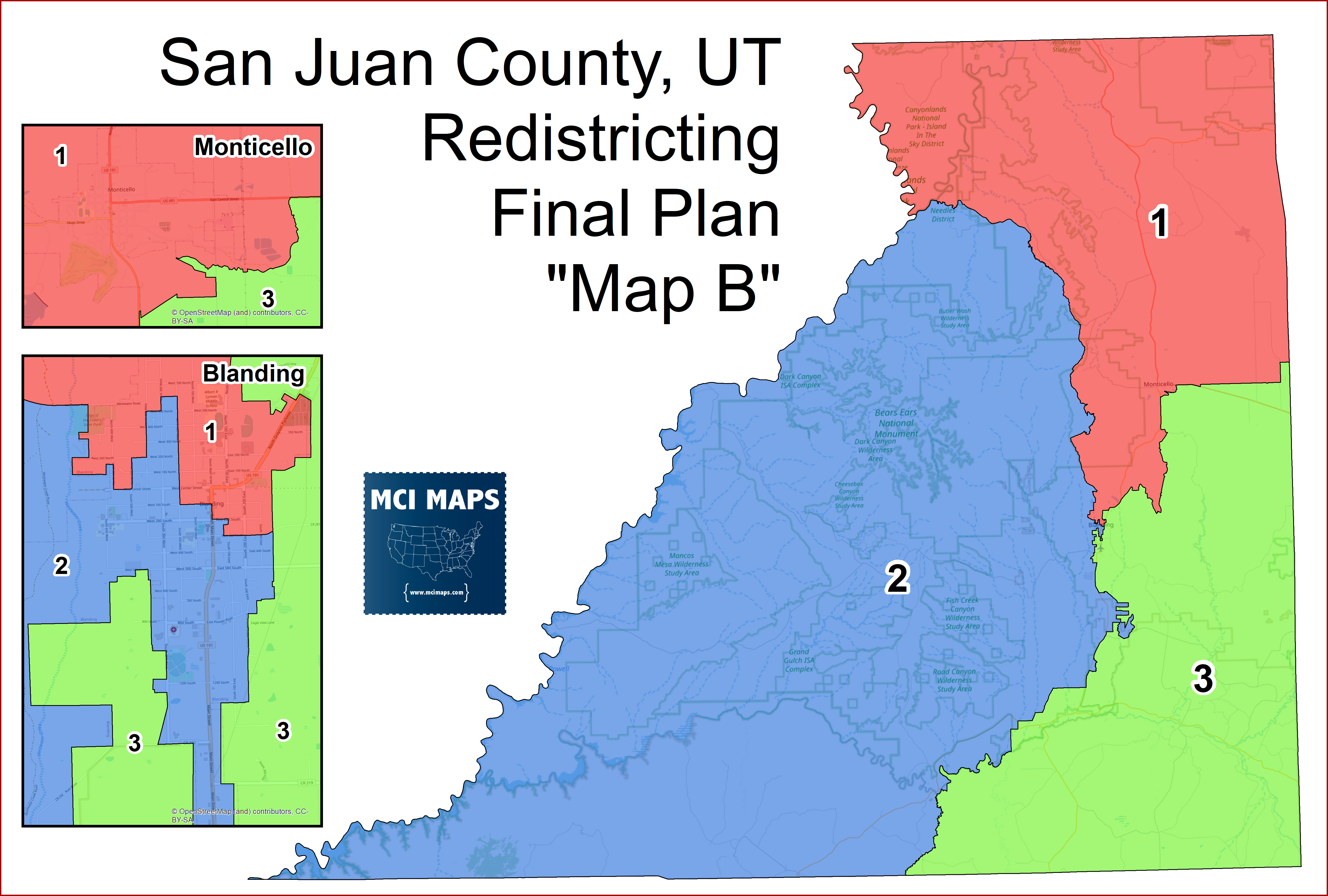

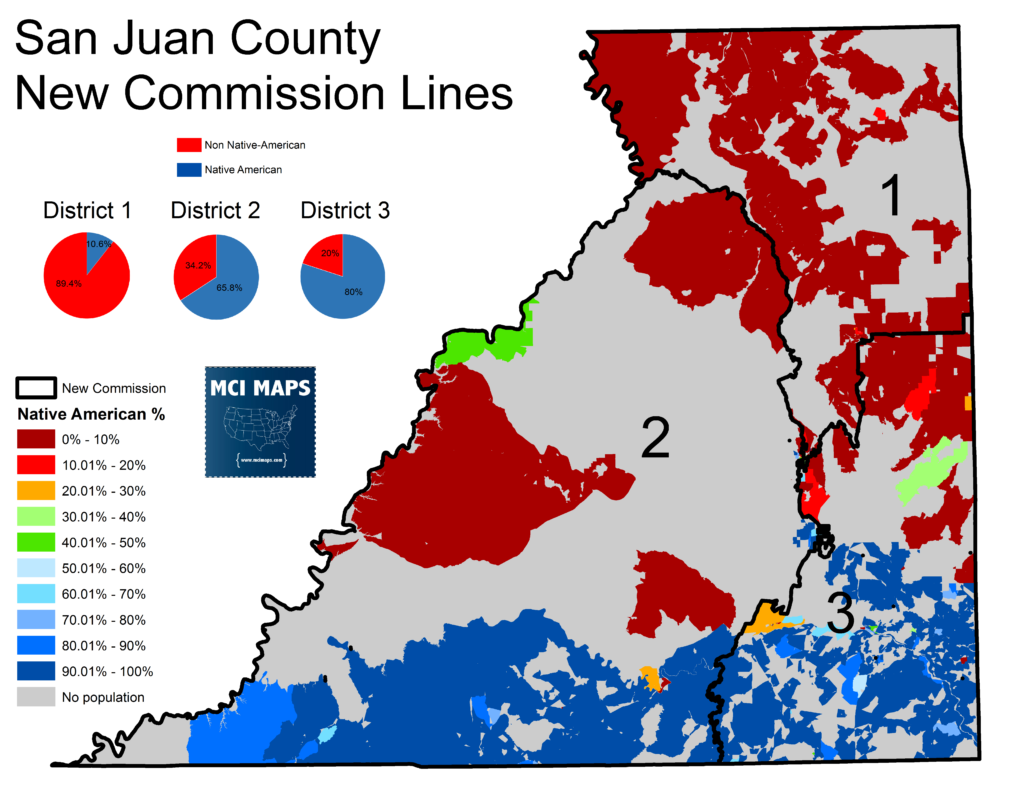

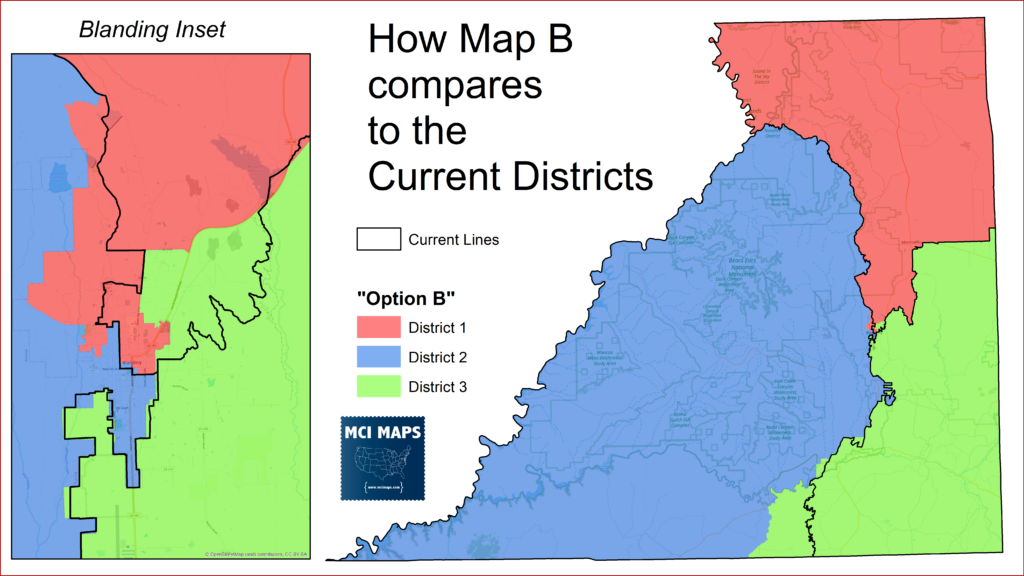

However, as the years went on, these district lines were never changed. The commission claimed they couldn’t make any changes. The Navajo Nation went to court and sued the county. In 2016, Judge Richard Shelby struck down the commission map, arguing district 3 was packed. The county went kicking-and-screaming into redistricting; exhausting appeals. The commission failed to produce any acceptable maps, leading to Judge Shelby assigning a special master to draw the final lines, which are seen below.

The lines, approved at the end of 2017, aimed to create a dynamic commission. District 1 is based in the north and is heavily White. District 3 is heavily Native and based largely out of the reservation. District 2 includes the Navajo Mountain western end of the reservation and parts of the city of Blanding. While its over 60%+ Native American, the turnout dynamics mean the seat is viewed as more split between white and Native voters. (For those who follow my Florida redistricting coverage, this is similar to dynamic with Hispanics in Miami-Dade).

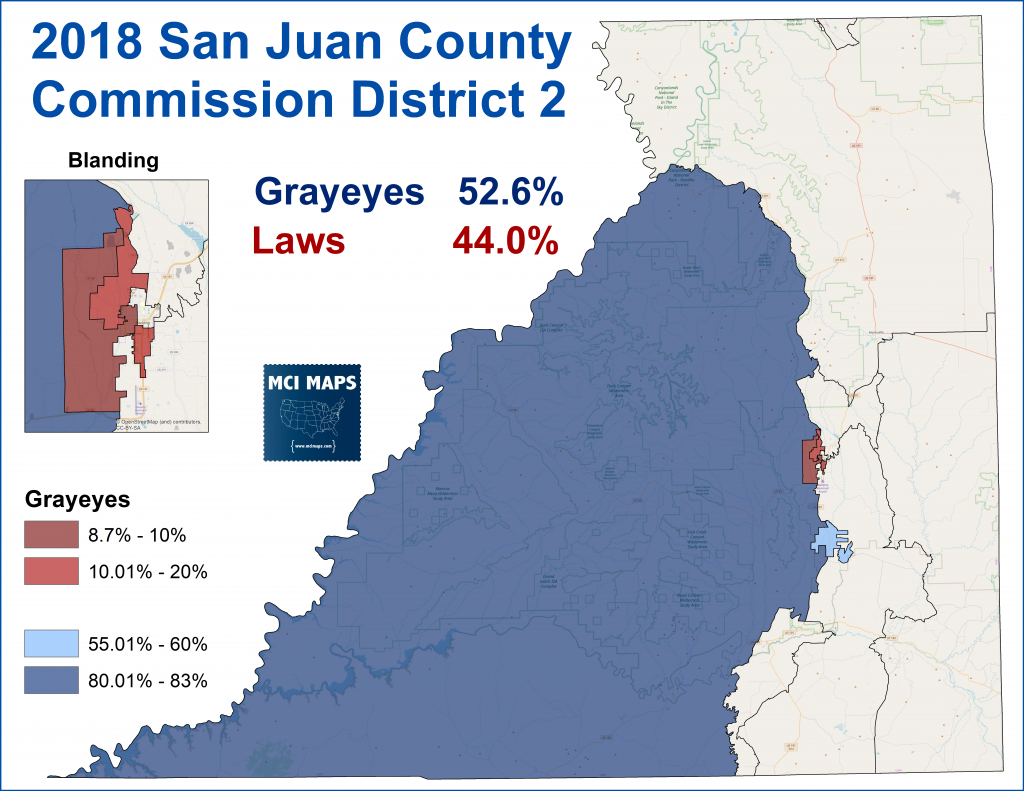

The 2018 midterms featured elections for all three seats. District 2, the new swing seat, was won by Navajo Mountain resident Willie Grayeyes.

This was a monumental win, and gave the Navajo control of the county commission for the first time in modern political history.

That race was filled with drama, including efforts to remove Grayeyes from the ballot before the election. Due to issues with postal delivery on the reservation, Grayeyes, like many reservation residents, got their mail across the border in Arizona PO Boxes. The San Juan County Clerk John David Nielson claimed this meant Grayeyes wasn’t a county resident and kicked him off the ballot. A judge restored Grayeyes to the ballot and admonished the Clerk for his brash actions.

2019 Referendum

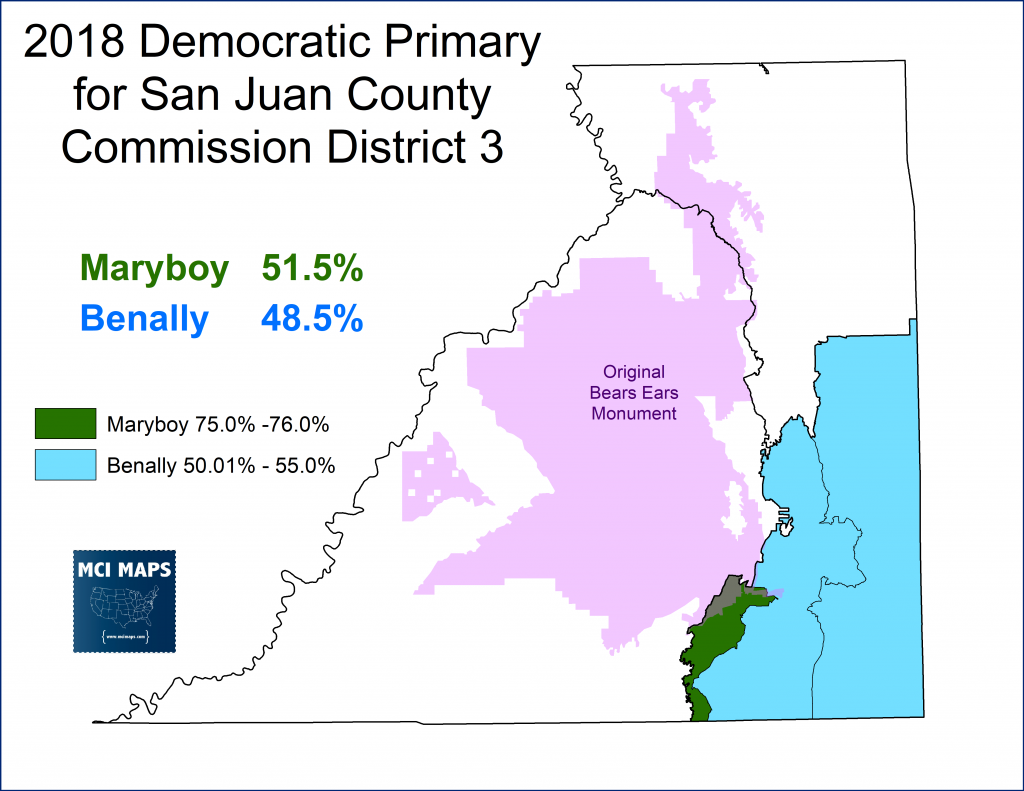

After the election of a Navajo majority board, the white residents of the north tried to find ways to reverse the change. Not only had Grayeyes won in district 2, but Kenneth Maryboy had won in district 3. This was the more safely Navajo seat, but it had been represented by Rebecca Benally, who broke with her Navajo constituents on different issues; especially the Bears Ears Monument. For those who don’t know, Obama added a massive monument designation before he left office: Bears Ears. This was a sacred location for the Navajo. Trump, however, would come in and shrink the size drastically. This angered many Navajo voters and leaders. Benally, however, had sided with the other San Juan commissioners in supporting the reduction. In 2018, she lost her primary to Maryboy.

With both Grayeyes and Maryboy, the county changed its position and wanted the original Obama-era designation restored. This was just one issue, but it represented a major sea-change for politics in the county; something the white residents came to viscerally hate. Commission meetings became increasingly nasty with complaints from the white residents of Blanding and Monticello.

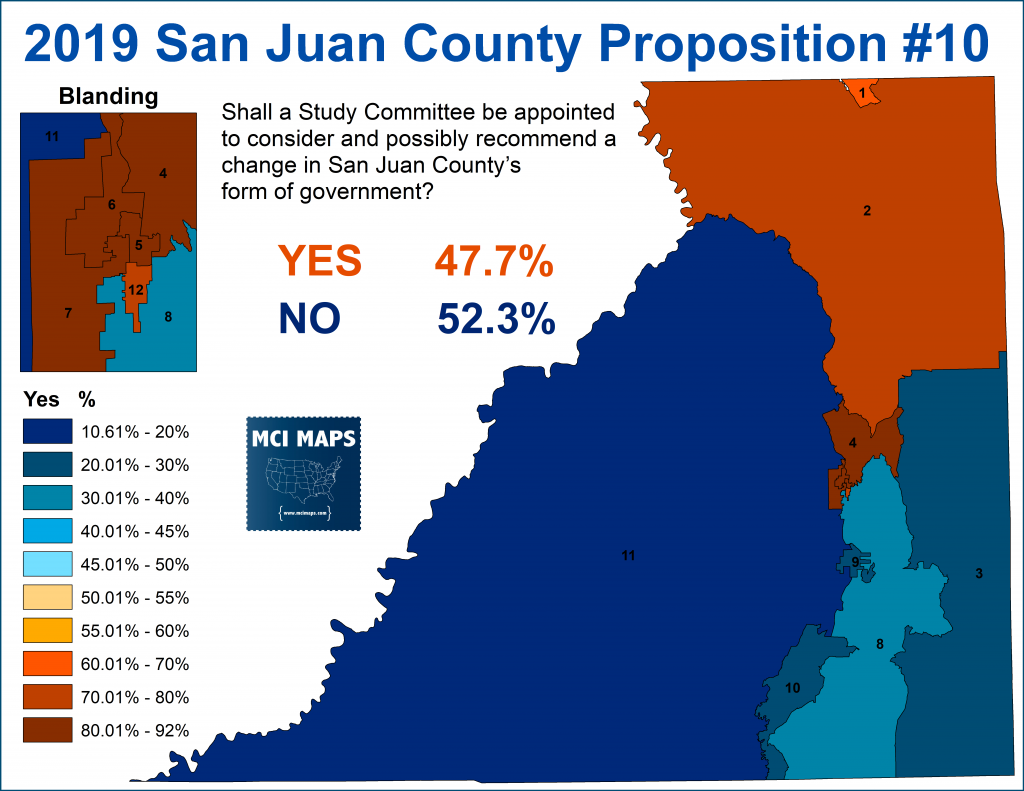

Later in 2019, Blanding Mayor Joe Lyman began to push petitions for a county proposition. Lyman complained about the city being split, and wanted a referendum to consider changing the San Juan form of government. This was a clear effort to alter the commission. The referendum was scheduled for November: Proposition 10.

The Navajo rallied against the measure. Meanwhile, the same Clerk of Court who’d removed Grayeyes from the ballot a year ago was caught electioneering by putting Pro-10 editorials at polling sites.

I wrote about the Proposition 10 campaign in my second San Juan article. The proposition would fail by 5% points. This was a major victory for the Navajo, as it represented one of their few county-wide wins.

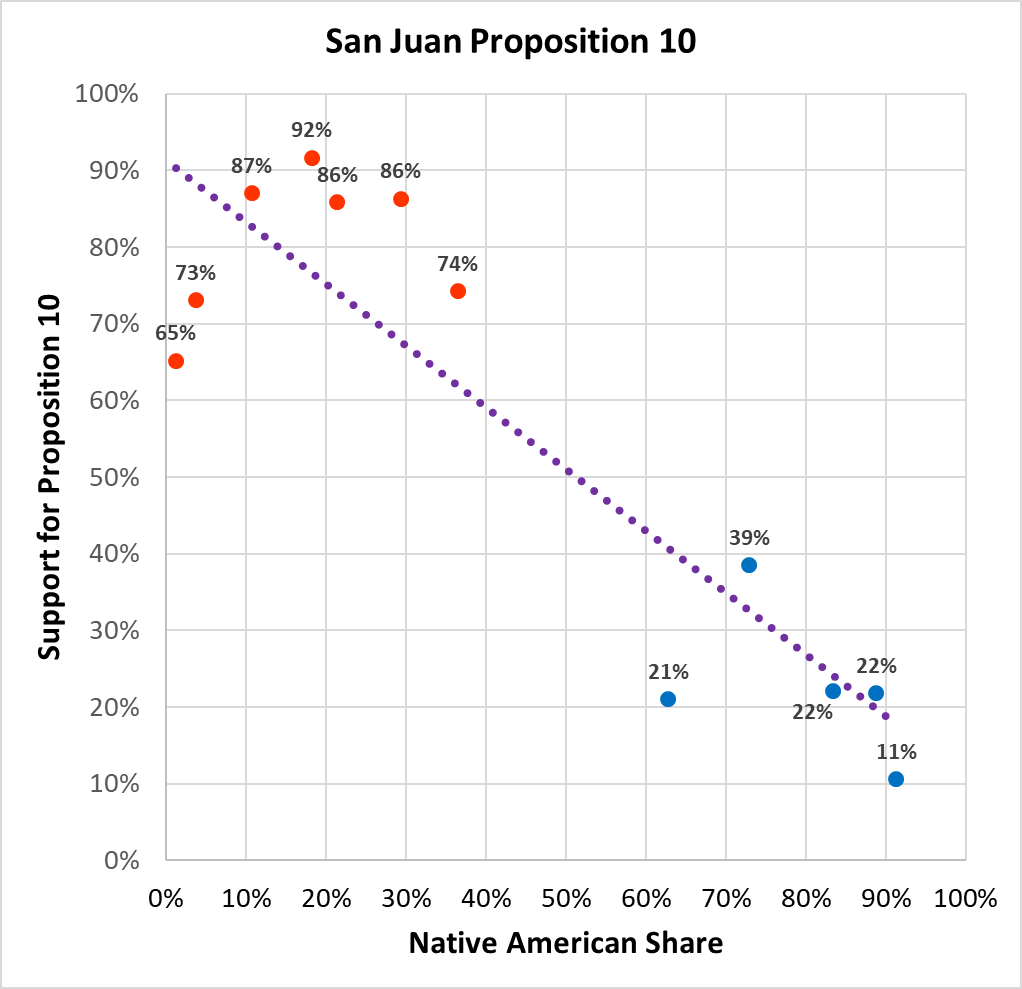

The vote was very racially polarized. All of the heavily white precincts backed the measure by large margins. Native-heavy precincts, meanwhile, overwhelmingly rejected the measure.

The victory was fueled by record-breaking Navajo turnout. It was a great moment, but it further poisoned relations within the county.

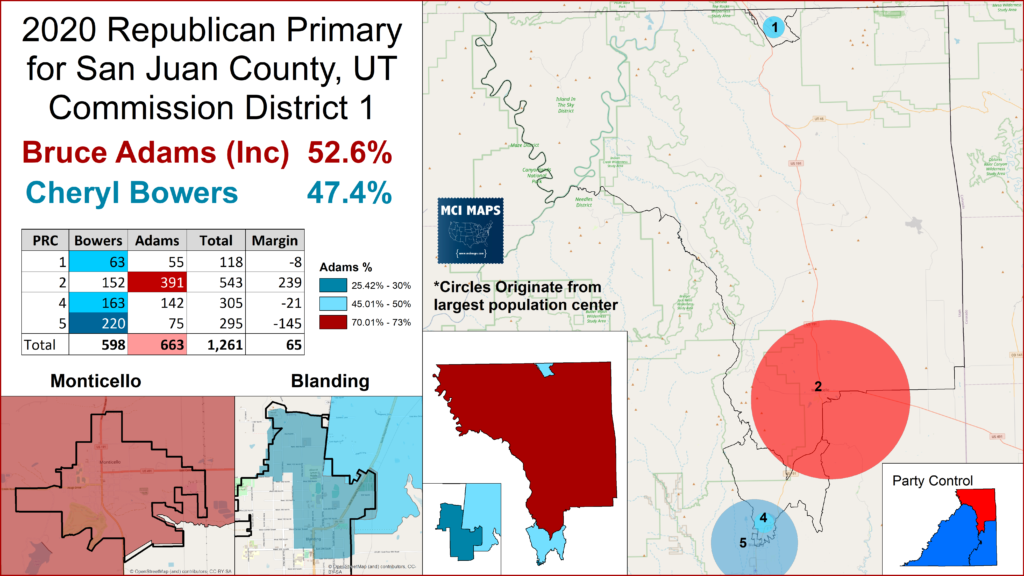

The 2020 elections saw no change to the board, as only seats 1 and 3 were up. District 1’s commissioner, Bruce Adams, narrowly won re-nomination for the Republicans; which is all that matters in such a red seat.

Adam’s margin of victory came from his base in Monticello. His opponent, Cheryl Bowers, was a Blanding city commissioner. This loss further fueled Blanding anger at its split. It was now on the losing side for District 2 in 2018 and District 1 in 2020.

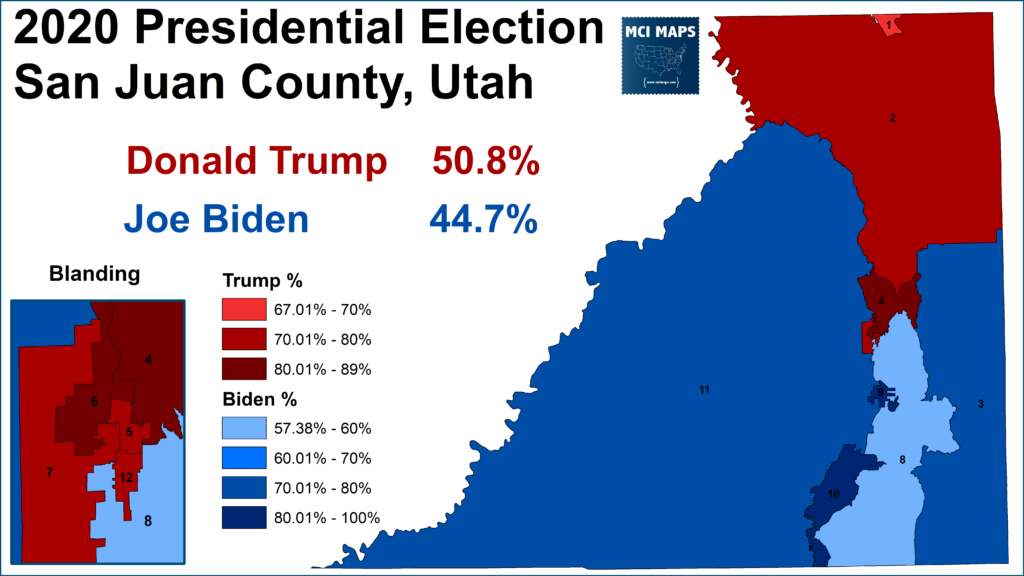

In the Presidential election, Donald Trump won the county by 6%. This was actually a notable Democratic improvement in the county. Trump won the county by 11% in 2016.

Navajo turnout was stronger than past Presidential cycles – a reflection of the activation that took place in 2019.

Redistricting for 2022

Considering everything that came before, redistricting for 2021/2022 was a fairly smooth process. The goal of the majority of the board, Commissions Grayeyes and Maryboy, was to create a least-change map. A least-change plan would be as close to the court-drawn plan as possible and continue to give Navajo members a chance to win a majority of the board. Once the census data became available, maps representing different interests began to be submitted.

The Different Plans Offered

To handle redistricting for 2022, San Juan County hired redistricting expert Bill Cooper to draft maps and guide the county through the process. This is very important, as Bill Cooper worked as an advisor for the Navajo Nation when they sued the commission over redistricting years back. This hire ensured an expert who would work to maintain the court-ordered status quo. Maryboy and Grayeyes voted to hire Cooper, while Adams voted no. Adam’s statement during the meeting sums up the acrimony already at play in redistricting – “I don’t support the whole concept. I’m not going to be a part of it.”

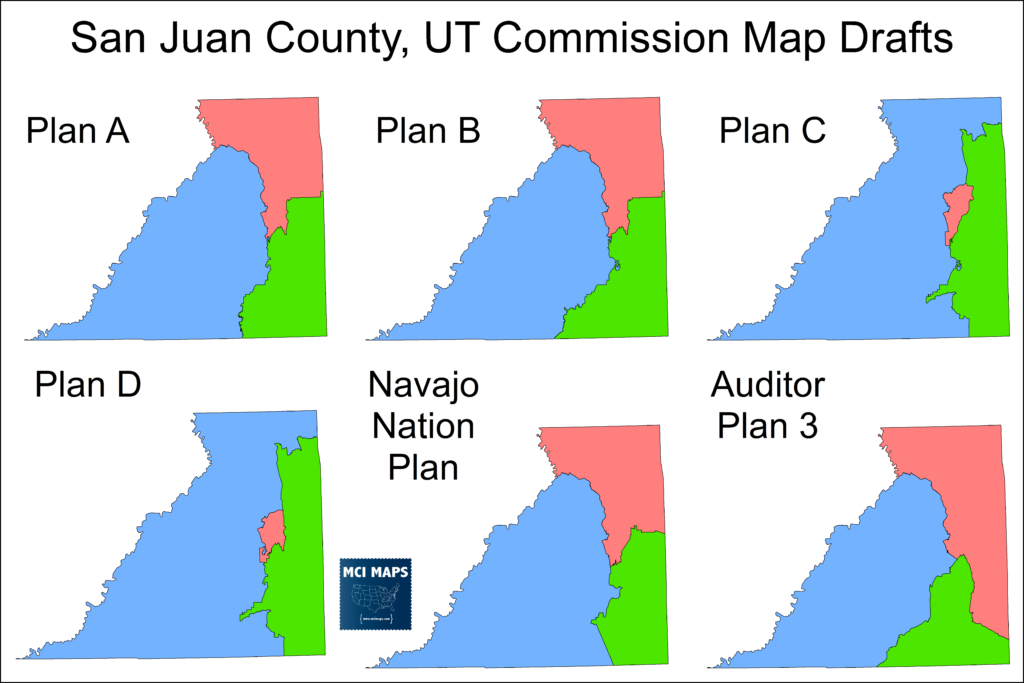

In total, five different plans were drafted for the Utah County Commission. All plans can be viewed here. A summary is as follows.

- Commission Plan A: The first least-change map drafted, which maintains the current racial dynamic

- Commission Plan B: A least-change map with different trade-offs from Plan A

- Commission Plan C: Keeps more of the City of Blanding whole

- Commission Plan D: Alternative plan that keeps Blanding whole, splits Monticello

- Commission Plan – Navajo Nation: The plan submitted by the Navajo Nation, similar to A/B.

- Commission Plan – Auditor 3: A plan submitted by the county auditor office staffer James Francom.

A visual of all plans is below. The links above have more details.

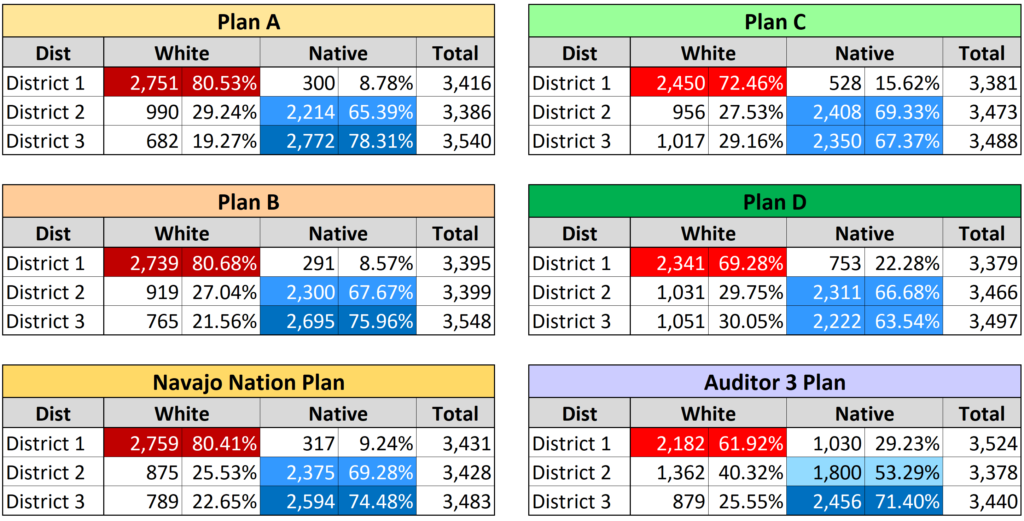

The racial data for all plans is seen below

The first plan presented by Cooper was Plan A. This plan aimed to make minimal changes and get the map to within the proper population deviation. Plan B, likewise, had a similar layout, but offered different micro changes. Both plans A and B aimed to keep the status quo. The Navajo Nation Plan also retained the status quo with its won take on shifts. One goal of the plan was to increase the Navajo population in District 2 to bring it close to District 3’s figures.

Plans C and D were a response to concerns from the city of Blanding. In the last redistricting round, residents of the city were upset their town was split. The town split is unavoidable when trying to maintain the minority thresholds for the seats. What hurts Blanding is that it is the center of the county and a large population hub. Blanding’s split was a major fuel for the 2019 ballot measure previously discussed. As a result of Blanding concerns, Cooper release plans to try and avoid the splits. Plan C kept most of Blanding whole. Plan D kept Blanding whole, but had to then split Monticello.

The final plan came from Deputy County Auditor James Francom. This plan aimed to reduce city and community splits. While it did this, it results in the 2nd Navajo seat only being 54% Native. As the courts cited in the original redistricting suits, a higher Native percent is needed due to turnout dynamics.

Debate and Final Plan

On December 21st, commissioners met again to decide on a final redistricting plan. Citizens were able to offer their opinions on maps via submission or in-person at the meeting. Many comments were legitimate discussion about the borders. Other comments were filled with… questionable…. comments about “ignoring race” and “we should just vote at-large.” It didn’t matter though, as it was never in doubt that the final map would be a least change option.

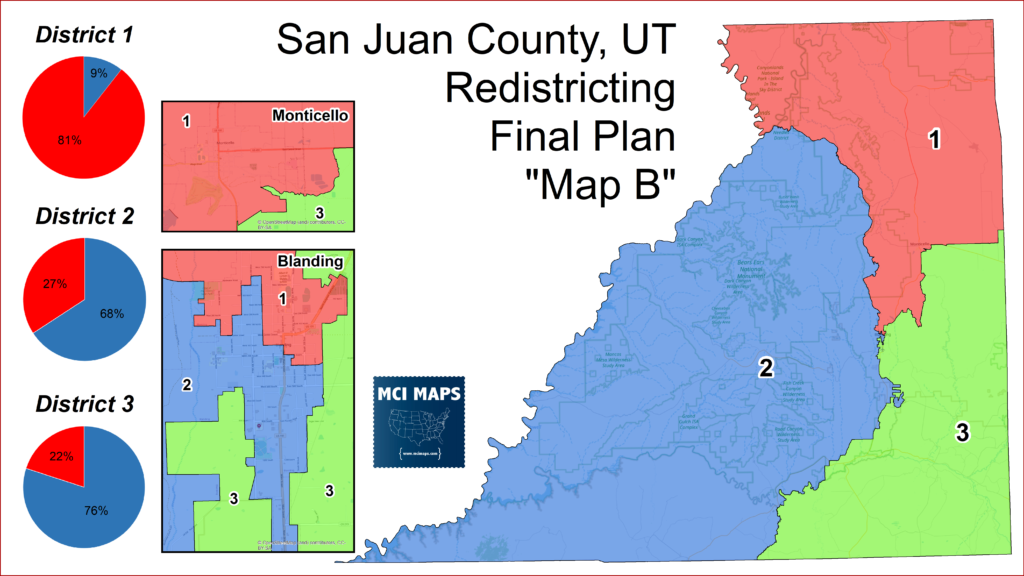

The commissioners opted for Plan B. Commissioners Grayeyes and Maryboy voted in favor, while Commissioner Adams voted against.

Similar to Plan A, the borders maintain the racial balance of the current map.

The plan passed only moves several hundred voters between commission districts. The exact breakdown of how many people are moved can be found here.

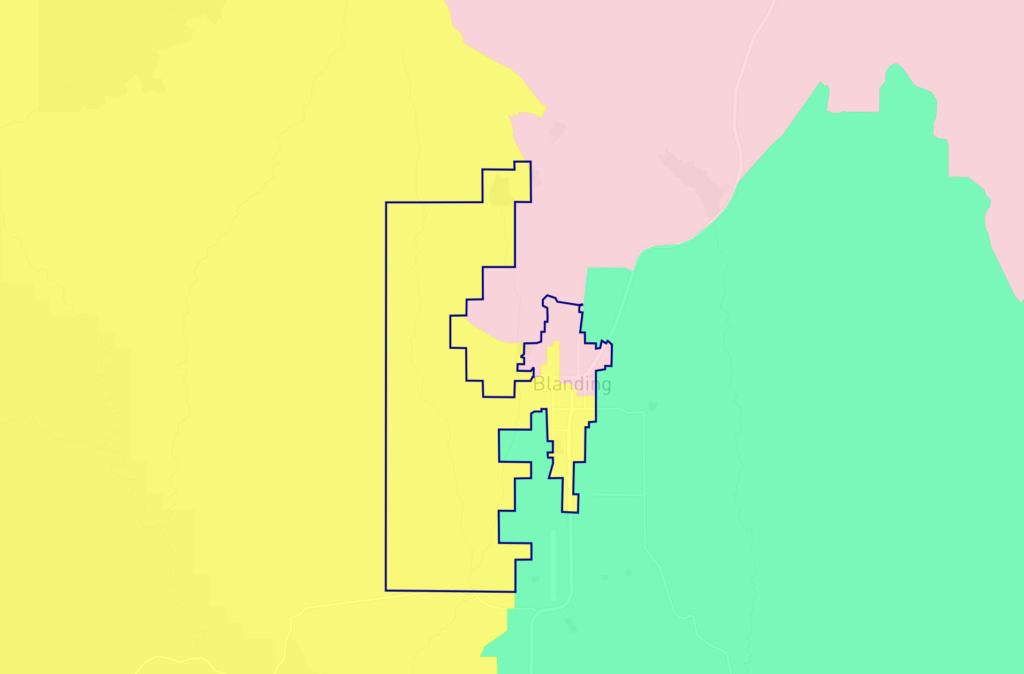

The City of Blanding remains split between the 1st and 2nd commission districts. The split was one of the major debating points of the maps. However, as previously said, keeping the city whole and balancing mandates from the court was not feasible.

The commission has actually gone back and forth on a few school board district proposals. Final ordinances passed on January 18th of 2022. With that, redistricting for San Juan County came to an end.

What’s Next?

With redistricting finished, the 2022 elections will be a major moment in San Juan political history. District 2 will be a major fight, and multiple countywide posts are up. After the 2019 victory, it stands to reason Navajo voters will try to test their hand at countywide offices, like Clerk or Attorney, that they never had a chance at before. The Navajo could instead focus on the District 2 defense if the cycle looks to go bad (its still a light red county overall). We will have to see. One thing is clear, however. The Navajo majority successfully defended their hard-won opportunity to have a say in government.