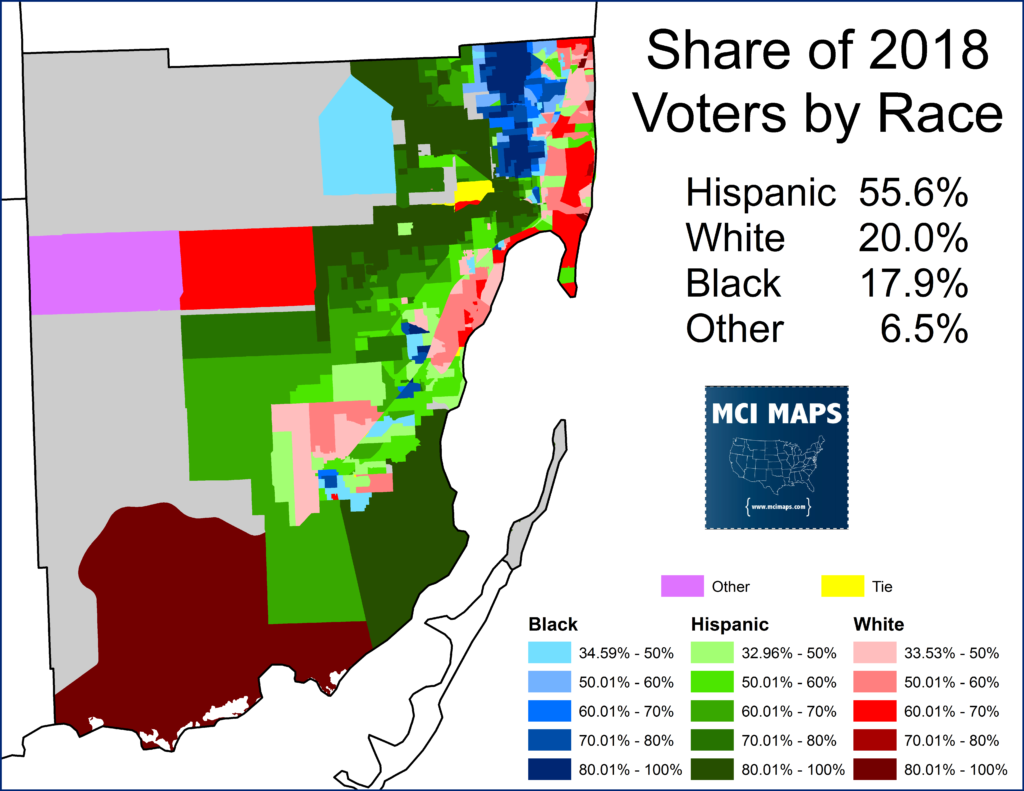

Earlier this year, I wrote about Miami-Dade’s performance in the 2018 elections. I touched on how unique Dade was compared with the rest of Florida and much of the nation when it came to race-based voting. Dade’s large Cuban population makes it a county where Hispanics lean more R than D; while its white voters are much more democratic. The area has always prided itself on its unique culture and it has no problem defying political norms.

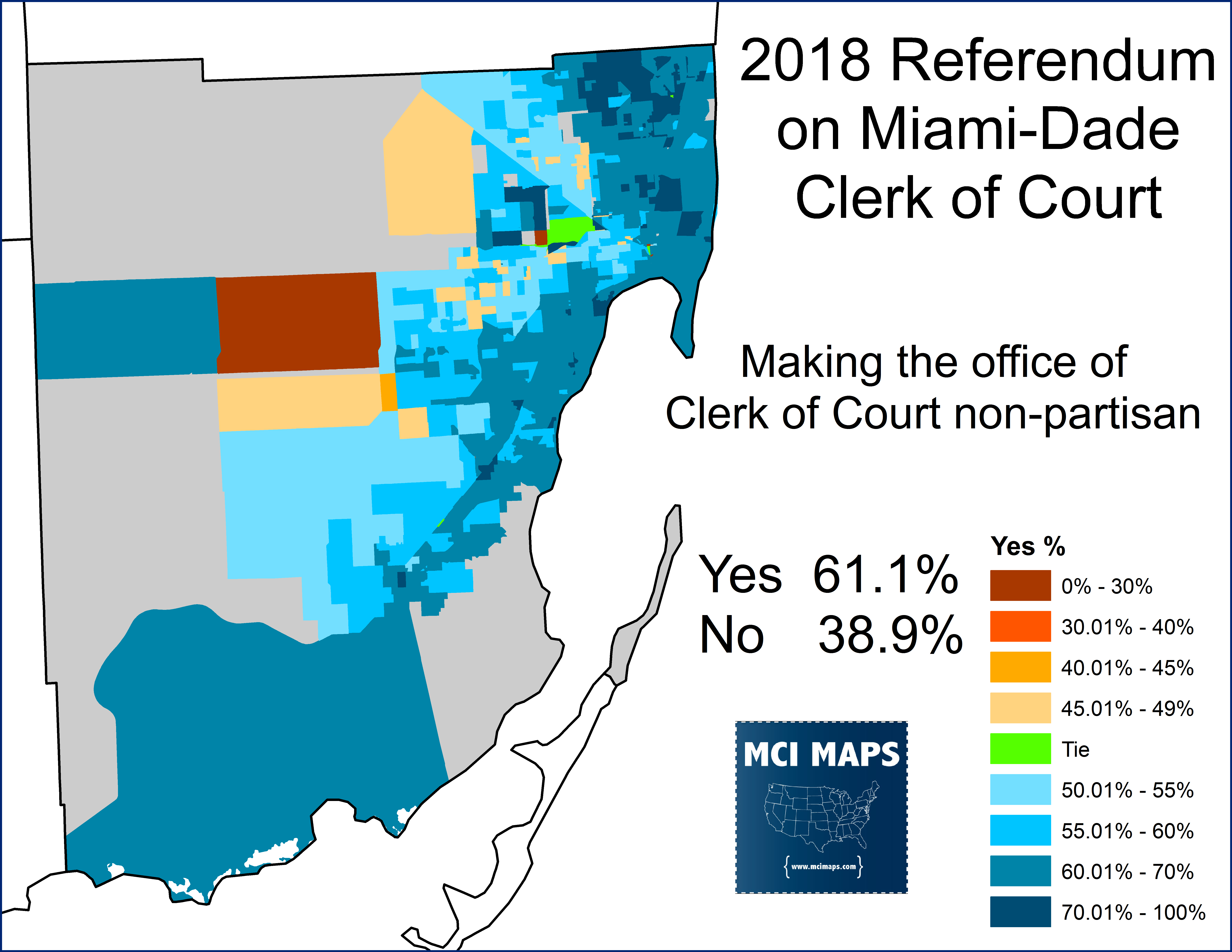

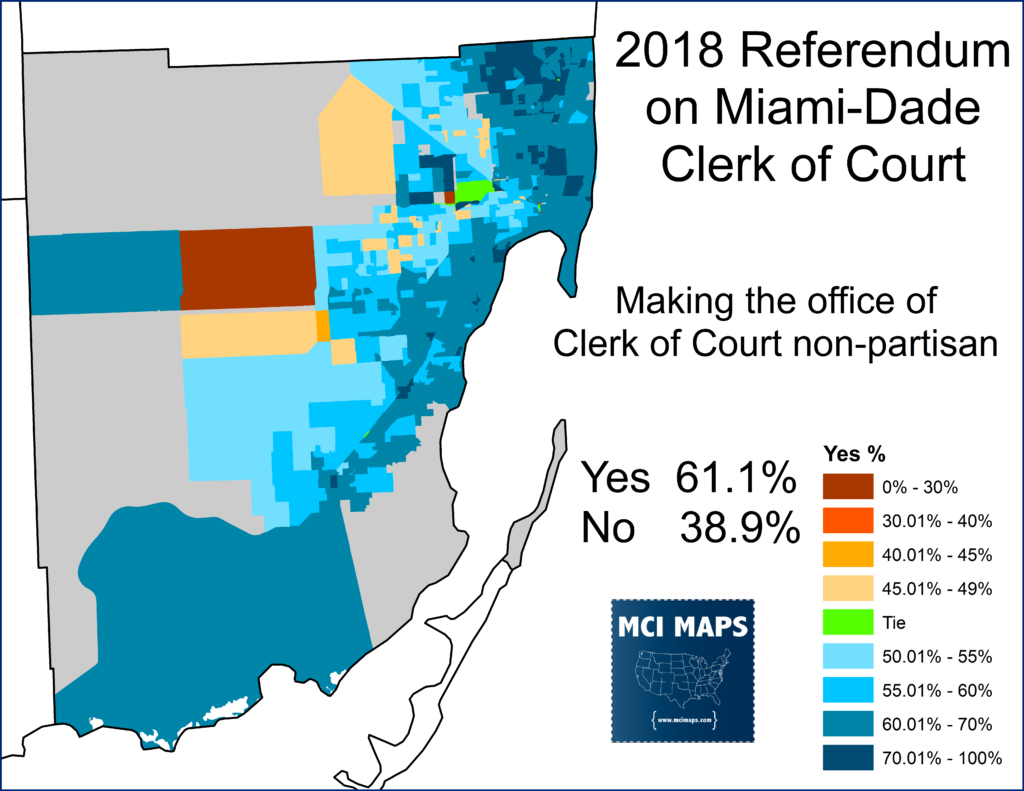

Buried in the pages and pages of election results from November in Miami-Dade County was a county referendum that did not get much attention. The ballot proposal, put forward by the County Charter Review board, aimed to change elections for the County’s Clerk of Court position from partisan to non-partisan. Even after the results were announced, it wasn’t until I delved into the precinct data that I really became intrigued.

The Partisan Fight Over Non-Partisan Elections

Lets clear one thing up right now. A large amount of the push for non-partisan elections in Florida is backed by political parties. Yes there are groups who support these measures who have no political agenda in mind. However, the reason politicians or boards support these proposals can often be political in nature. When it comes to county-level offices, you see the push for partisan or non-partisan elections often emerge from the political party that normally has trouble winning. Republicans tried to push non-partisan elections for county officers in Hillsborough just last year. Meanwhile, Democrats were all the more willing to support a similar push in Wakulla a few years before that. These issues can get especially heated when race is considered. A proposal for non-partisan officers in Leon County would have diminished African-American voting power, something I wrote about here, and opposition from the local NAACP killed the momentum for that change.

When referendums to make county offices non-partisan appear on the ballot, its generally popular. To voters it sounds good. Sure. Who doesn’t want to get politics out of local offices? I delved into some issues with this logic in my Leon article, but that is not the purpose of this write-up. In general, voters like it. Even if a measure is pushed by one party (the politicians or consultants in this case) or the other, voters don’t often see that backstory and to them it just sounds like a good proposal.

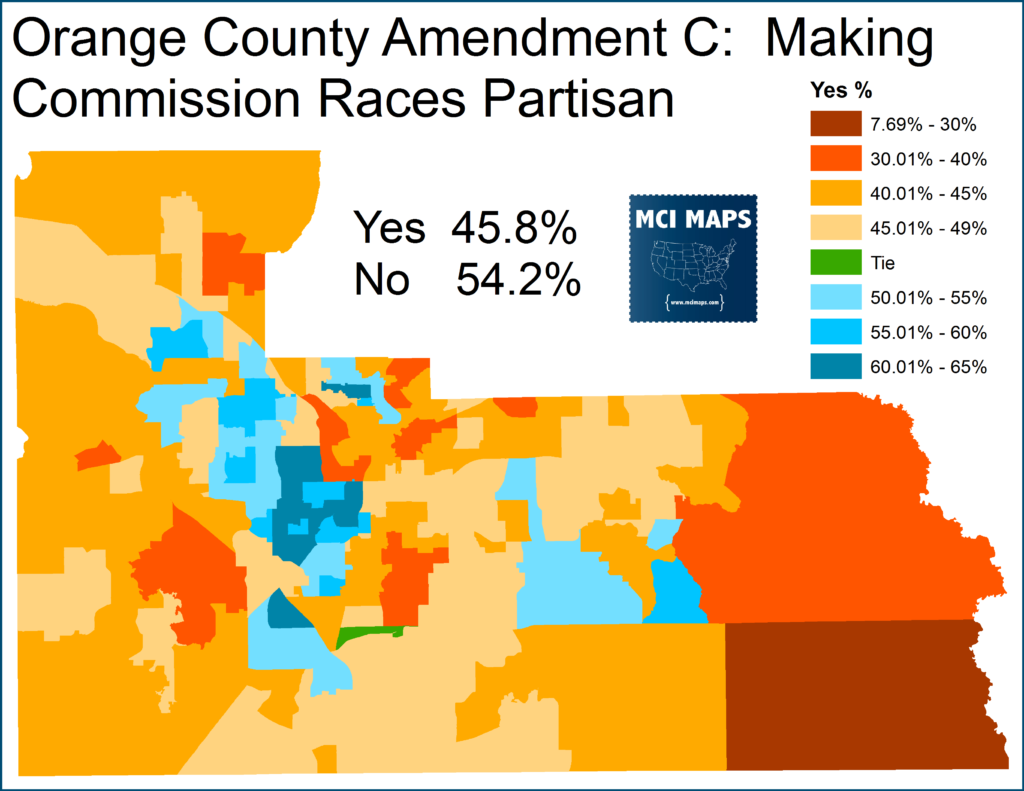

Orange County

Now while voters generally support these proposals, there are still some electoral trends visible when these referendums are held. Orange County is the most recent example – with referendums in 2014 and 2016 over the issue of races being non-partisan. In 2014, they held a referendum on whether to make the already-nonpartisan county commission a partisan chamber. Democrats pushed this and Republicans opposed it. Why? Because Orange County is a very democratic area at this point but at the time still had a Republican-majority county commission thanks to candidates not having to run with a party label next to their name.

The referendum failed. It did win in several areas but overall fell short.

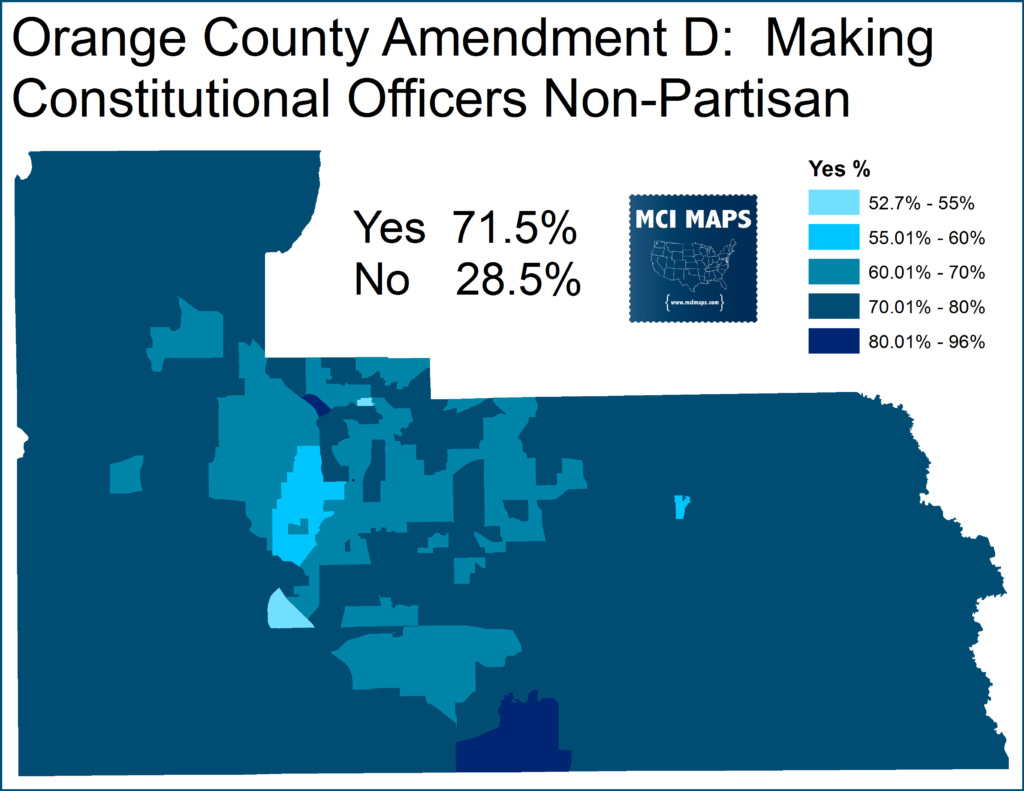

That same day, a referendum was held, this one backed by Republicans, that would make the Constitutional Officers (Tax Collector, Sheriff, and so on) non-partisan. This easily passed. Voters are especially supportive of making these types of offices non-partisan. “How can being Tax Collector be partisan.” Well, as I argue here, it can, but that’s not the point. Voters supported it everywhere, but there were some areas were it had less support.

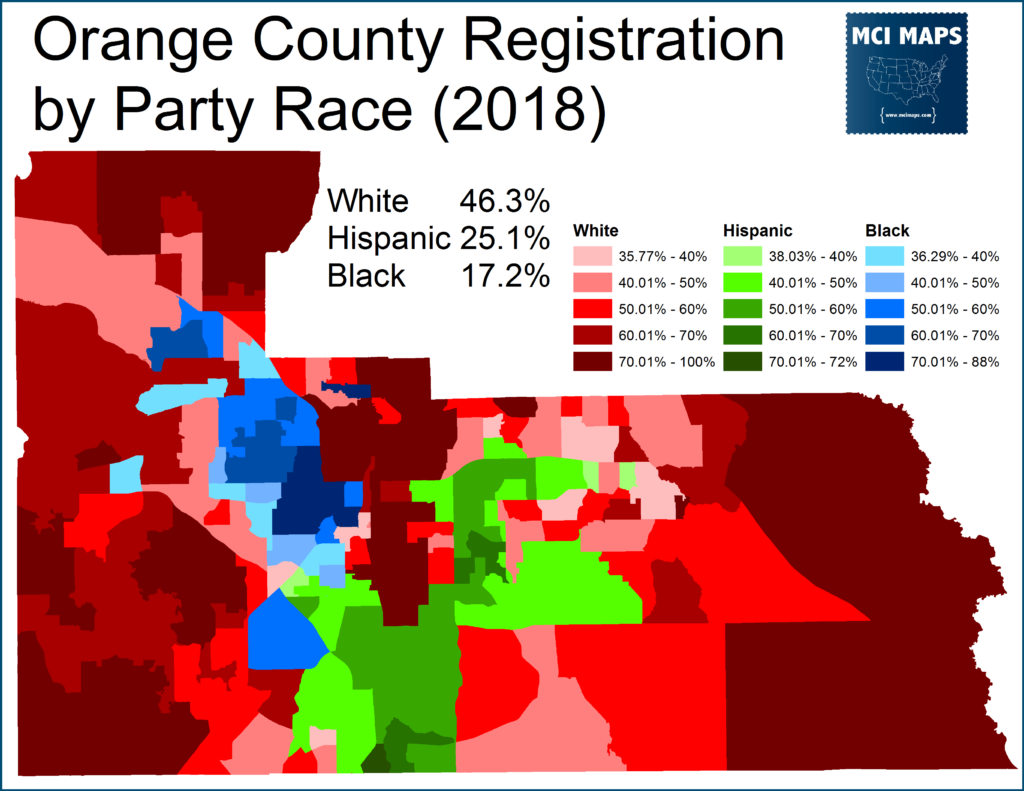

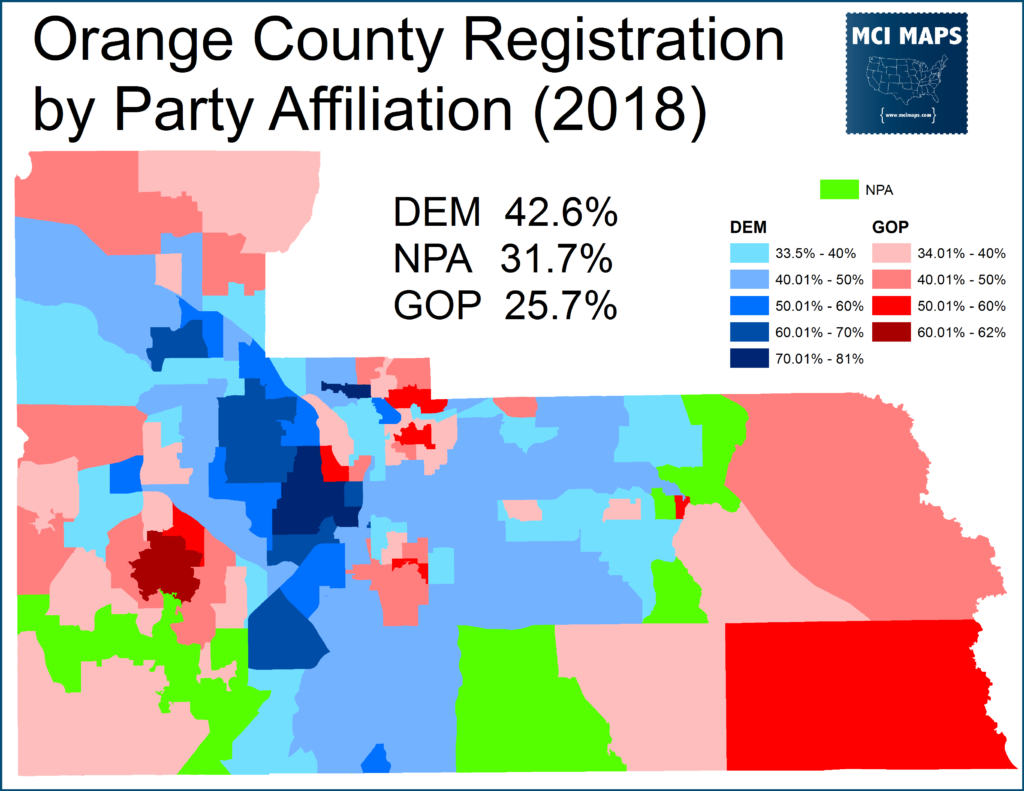

Now, with those precinct maps in mind, here are the race and partisan makeup of Orange County.

What you see if the results match with racial and partisan lines to a general degree. African-Americans were supportive of making the commission partisan and more iffy on making the constitutional offices non-partisan. Democrats were more iffy in general and Republicans were much more on the non-partisan bandwagon.

Miami-Dade’s Unique County Government

Miami-Dade has a different county government from much of the state. Most counties operate with a county commission and several constitutional officers. Most counties elect a Tax Collector, Clerk of Court, Sheriff, Supervisor of Elections, and Property Appraiser (which I am referring to as the “Big 5”). Several also elect School Superintendent. Miami-Dade, however, only elects Clerk of Court and Property Appraiser. It then elects a 13 member county commission and a county Mayor. The other positions (like Sheriff, Elections) are appointed by the county government.

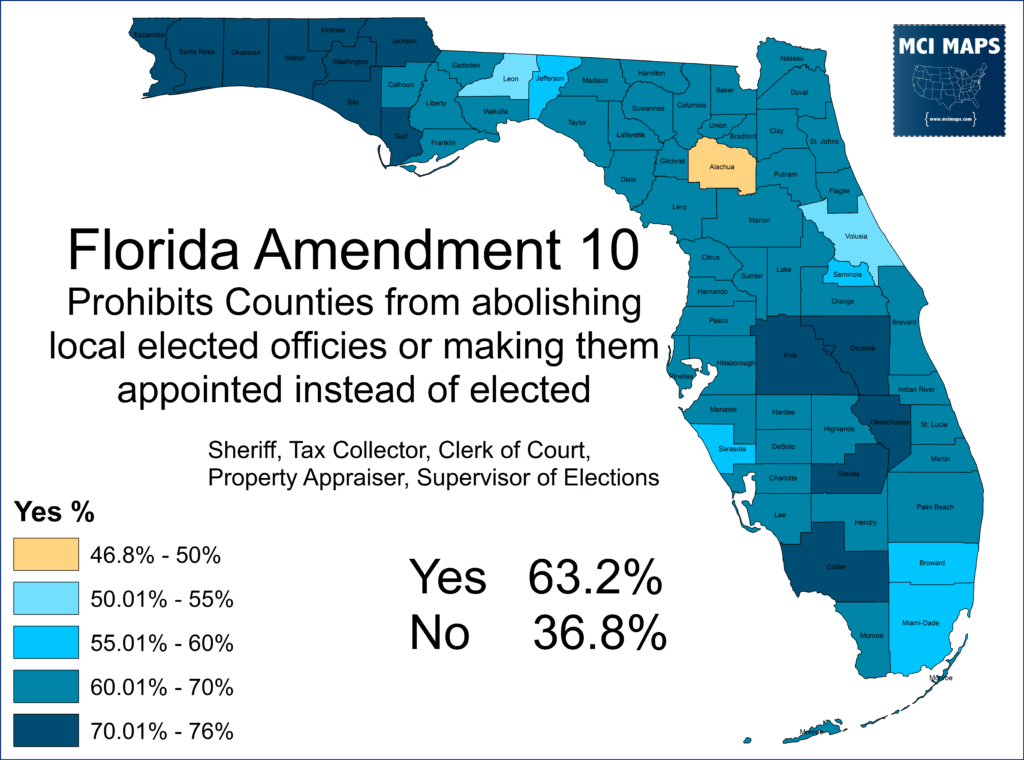

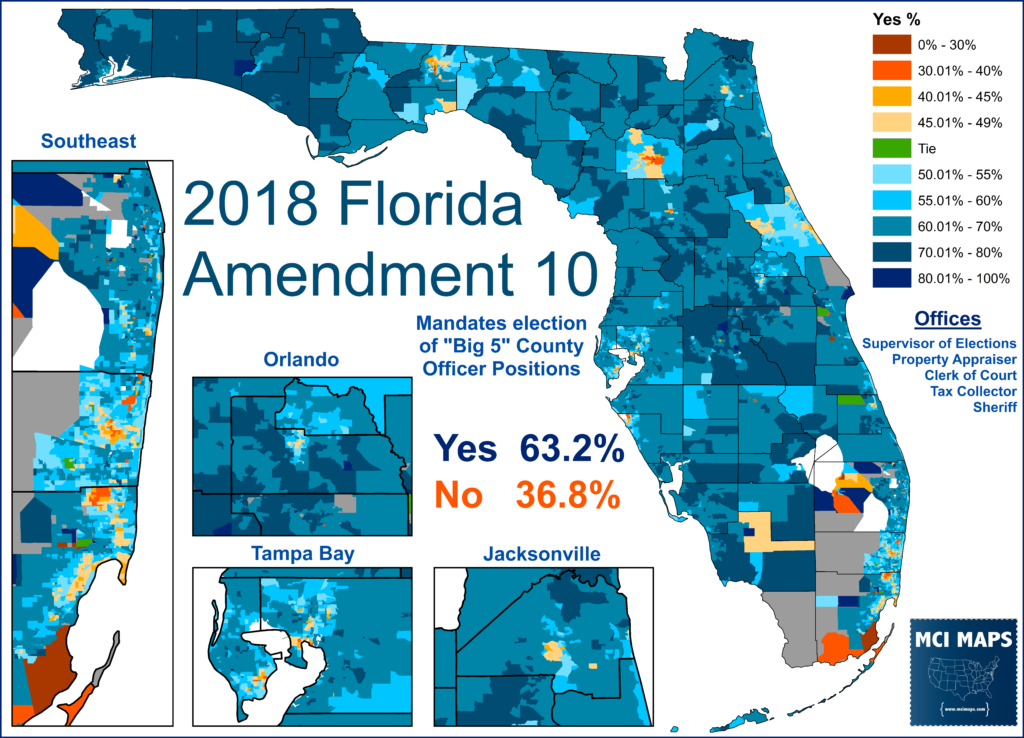

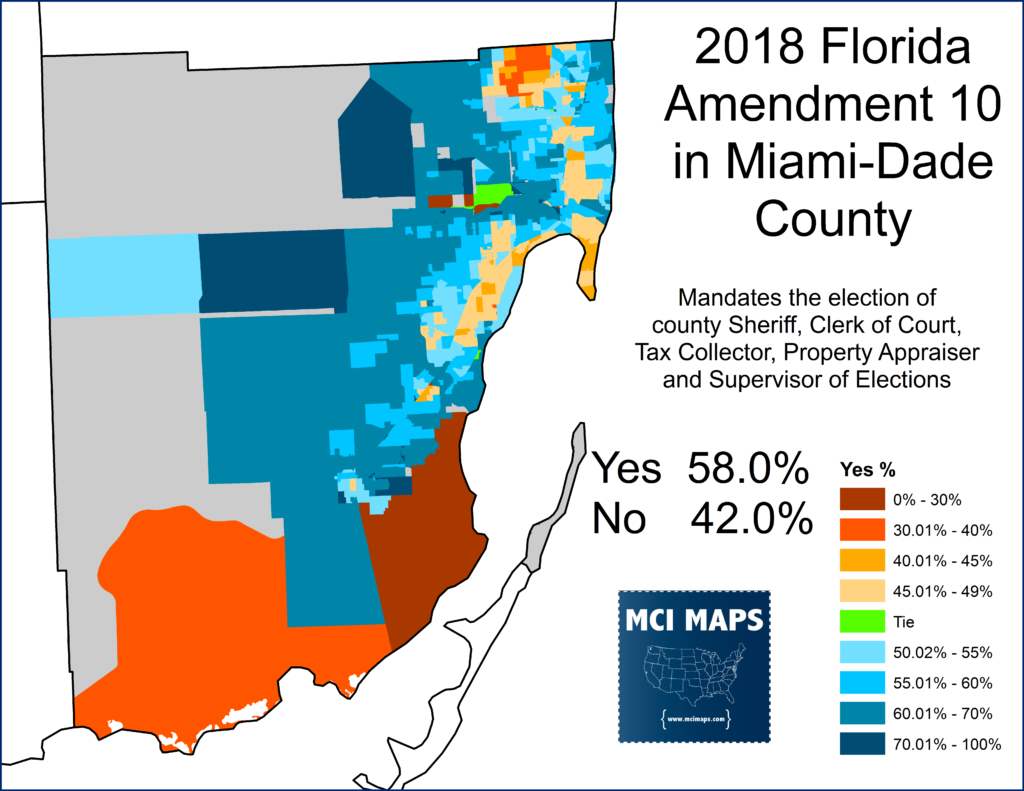

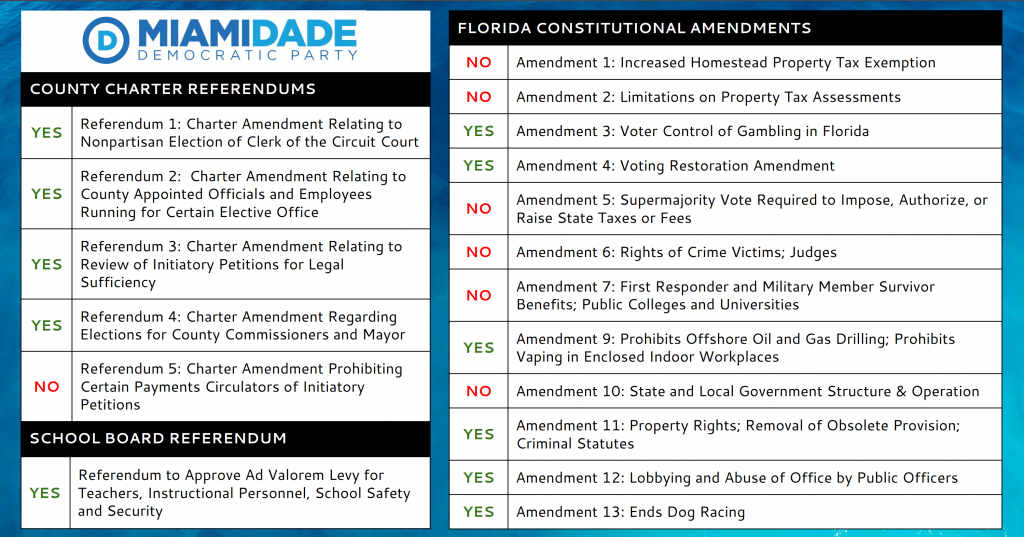

A few counties, like Broward and Volusia, eliminated their elected Tax Collectors years ago, but no county elected just two of the ‘Big 5’ officers. Then, in 2018, Amendment 10 passed, which mandated each county elect the ‘Big 5’ offices. Miami-Dade politicians attacked the proposal, arguing it violated their Home Rule. However, the measure easily passed statewide and in Miami-Dade.

The measure secured 58% in Miami-Dade. It’s weakest areas were African-American heavy Miami Gardens (on the northern border) as well as several white communities along the coast. Other black communities backed the measure as well as most Hispanics.

The law will go into effect in 2024 and will lead to the election of three more offices in Miami-Dade. What is notable is how more Democrats than Republicans seemed to oppose to the measure – despite the fact the county will likely elect Democrats to the positions. Cuban Republicans, meanwhile, were broadly supportive of the measure; even though they have a better chance getting officials from their community via the appointment method than they do countywide elections.

The Non-Partisan Clerk Referendum

The same day the measure passed, the county hadits own referendum on making Clerk of Court, a position it already elected, non-partisan. Before this, Clerk was elected on a partisan ballot and Property Appraiser elected on a non-partisan ballot. Longtime Incumbent, Democrat Harvey Ruvin, hasn’t faced a real threat in years.

The proposal was put on the ballot via the county’s charter review board. The proposal was backed by major groups and Ruvin himself. Meanwhile, in a county becoming more blue overall, the Miami-Dade Democratic party supported the measure.

The measure was strongest in Democratic areas of the county – doing well with whites and African-Americans.

The Miami-Dade Democratic Party actually recommended a YES vote for this proposal – despite the obvious lack of strategy in such a decision. They also opposed the statewide Amendment 10, which we already discussed.

Meanwhile, Cubans were modestly supportive with several Cuban precincts voting no. Again this is the opposite result than should be expected IF voters were thinking strategically (obviously they weren’t). Cuban Republicans would absolutely want this office non-partisan to give them a better shot at winning an office. Meanwhile, Democrats should have wanted the D to remain next to the name. This result has a near opposite trend from what was seen in Orange County, where more Democratic voters were opposed or iffy on making offices non-partisan.

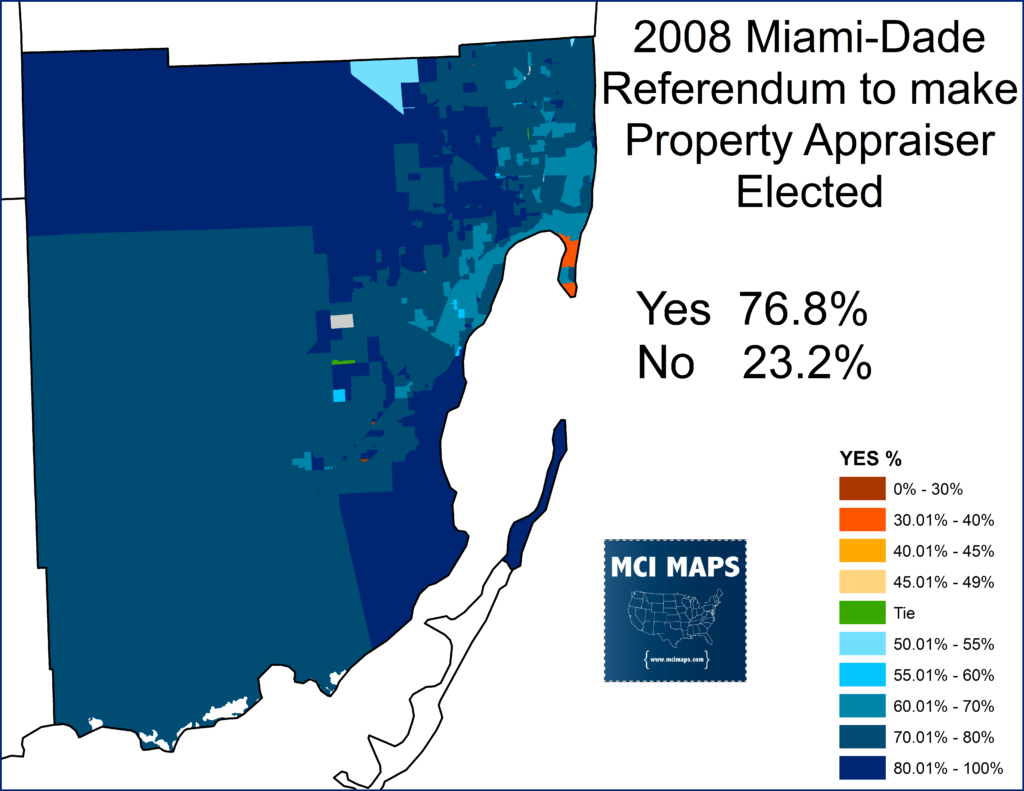

The 2008 Dade Property Appraiser Election

Before 2008, only one office in Miami-Dade was elected: Clerk of Court. In January of that year, the voters approved a proposal to make Property Appraiser elected. It passed overwhelmingly with 77% of the vote.

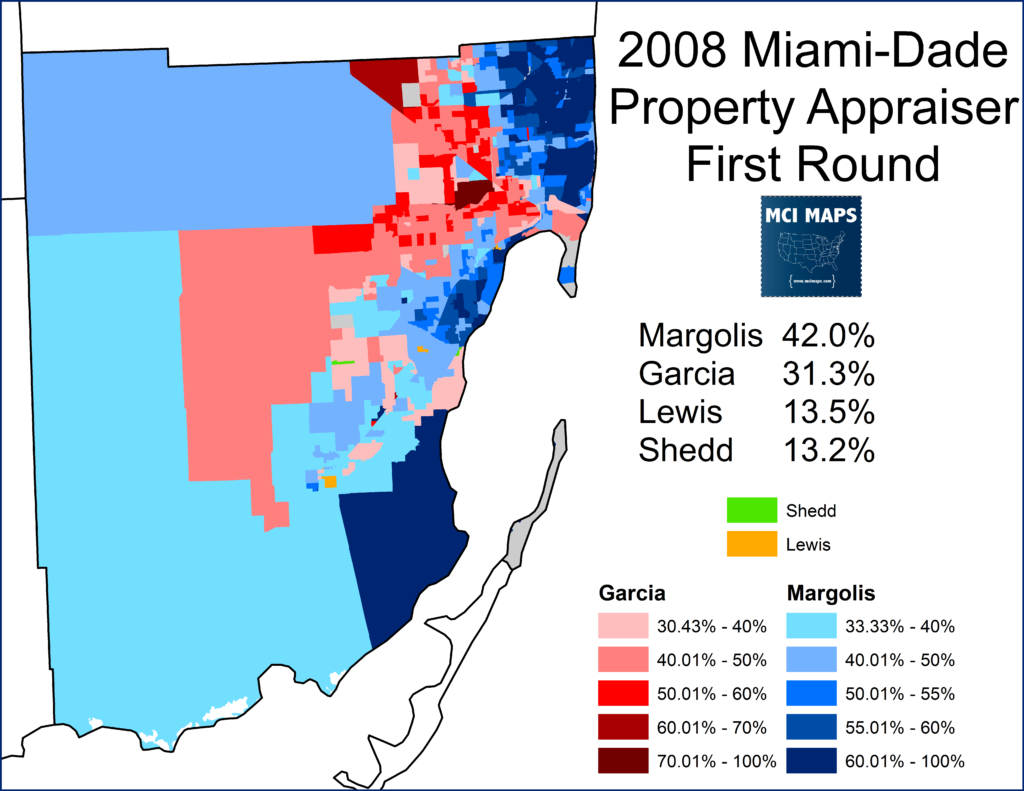

The front-runner for much of the race was State Senator Gwen Margolis; a white democrat. Margolis was an institution in Dade, serving as state senate President in the early 1990s, a county commissioner afterward, and then state senator again. Margolis’ opposition rallied around Pedro Garcia, a Cuban Republican veteran property appraiser. The first round of voting was held in November of 2008; with Margolis winning easily. The race fell along similar party lines – with Margolis dominating with African-Americans and whites, while Garcia won with Cuban Hispanics. All this happened on a non-partisan ballot.

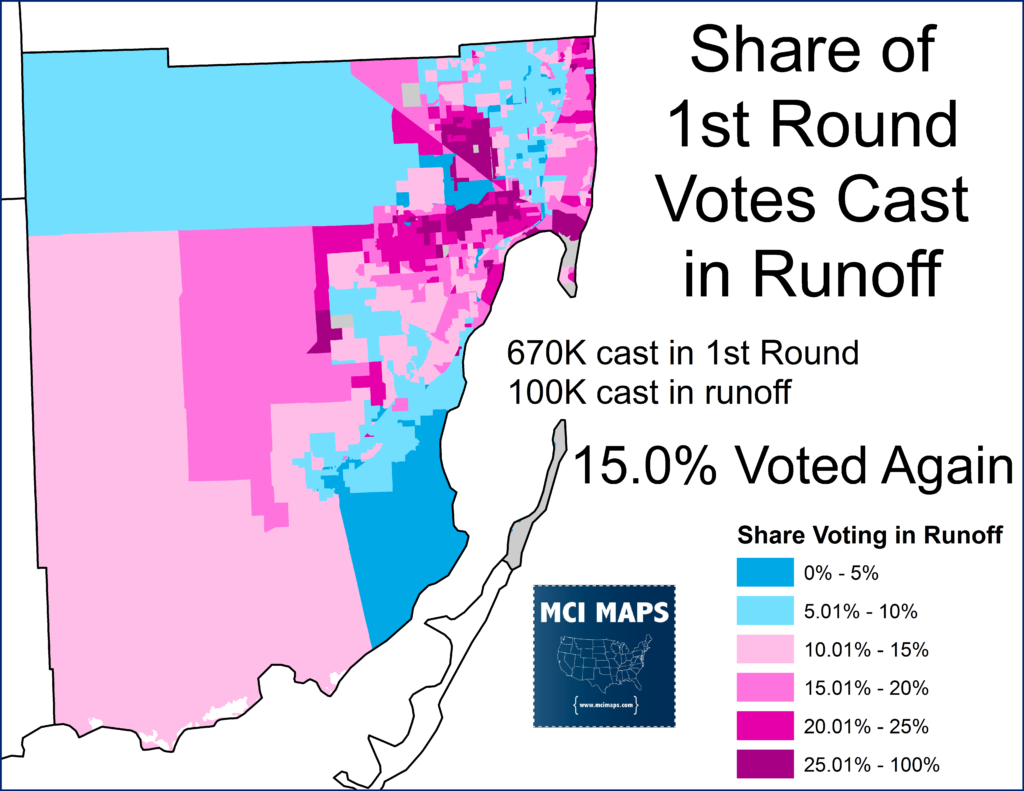

However, since no one got 50%, a runoff as needed. When most counties do these non-partisan races, they hold the first round during the August primaries and the runoffs in the November general. Dade, however, was holding its runoff in December. Turnout was expected to collapse.

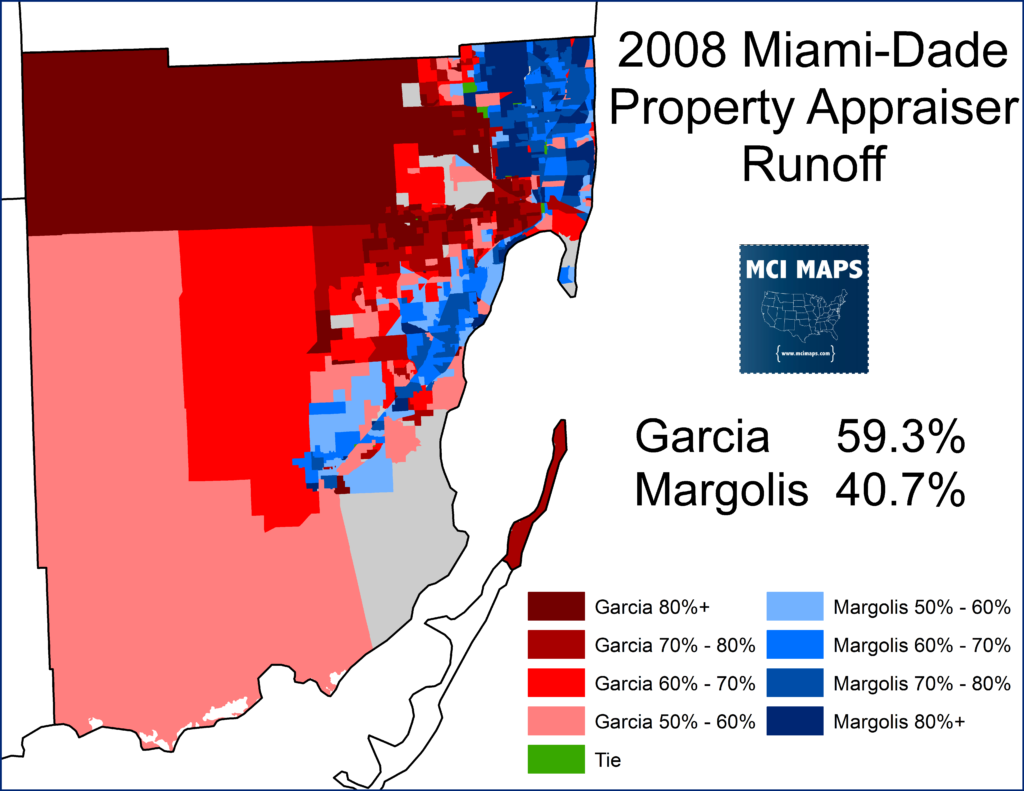

Margolis sued to stop a runoff from happening, arguing that since partisan constitutional offices had no runoffs, this shouldn’t either. She lost the ruling and lost the runoff in a 20 point landslide.

The lawsuit likely did not help Margolis’ standing with voters, but there is a clear reason she was suing – she knew a runoff would be trouble for her. The turnout drop between November and December was going to hit hardest in Democratic areas. In Dade, one of the groups with the best turnout history is older Cuban voters; a group that heavily leans GOP and backed Garcia in both rounds. Cuban voters vote heavily absentee and overall turnout well in low-turnout affairs. Sure enough, when you compare the turnout between the first and second rounds, we see that Cuban areas and the coast had the best retention rate.

Only 15% of voters from November cast ballots again. It didn’t even reach 10% in African-American precincts, but did top 20% in dense Cuban precincts. This dynamic allowed Garcia to win.

Democrats have never been able to make a serious play for Miami-Dade Property Appraiser sense. Considering this tale, one would think the Democratic Party of the county would have opposed the Clerk move to non-partisan.

Conclusion

Miami-Dade is a unique county. The largest in Florida, it has moved from swingish to a solid Democratic vote block. However, as this article, and my earlier examination of 2018 showed, the county defies many political trends. What this article especially highlights is how voters and parties operate differently in this county than one might expect. The Clerk of Court referendum and Amendment 10 debate both highlight this.

In fact, for folks who follow politics and Youtube’s popular “Crash Course: World History” series – it becomes very clear that Miami-Dade is, indeed, The Mongols.