Wisconsin’s April elections were an absolute mess. No one can deny this. April 7th, which served as the General Election for a State Supreme Court race, a litany of municipal general elections, and the Presidential Primary, took place amid the Coronavirus, or COVID-19, pandemic. As states and countries across the world were locking their economies down stop spread of the virus, the issue of Democracy and Pandemics came up. When do you delay an election?

Wisconsin’s Moves Forward

The issue of delaying an election is something multiple states have grappled with. Most states that didn’t get their elections in by mid March opted to move their primaries till later in the year. The last big batch of states to hold in-person voting was on March 17th; when Florida, Arizona, and Illinois held their primaries. Ohio was scheduled to vote that day as well, but Governor Mike DeWine postponed the vote the day before it was to begin. Several other states, like Alaska and Wyoming, moved their Democratic primaries to entirely by-mail.

For weeks, however, it looked like Wisconsin was aiming to move forward with its races. One issue pointed out was that many of the municipalities with elections in April were going to see the terms of their current office holders expire in the same month. Through the entire month of March, Governor Tony Evers remained opposed to postponing the election; even as localities reported they would have serious shortfalls in staffing on election day. Reports of poll worker shortages began to come up in March. It was anticipated many polling locations would need to be consolidated. Many cities saw reductions in their voting locations, but none seemed to be worse than the city of Milwaukee, which in the end only had 5 of its 180 still operating by the end.

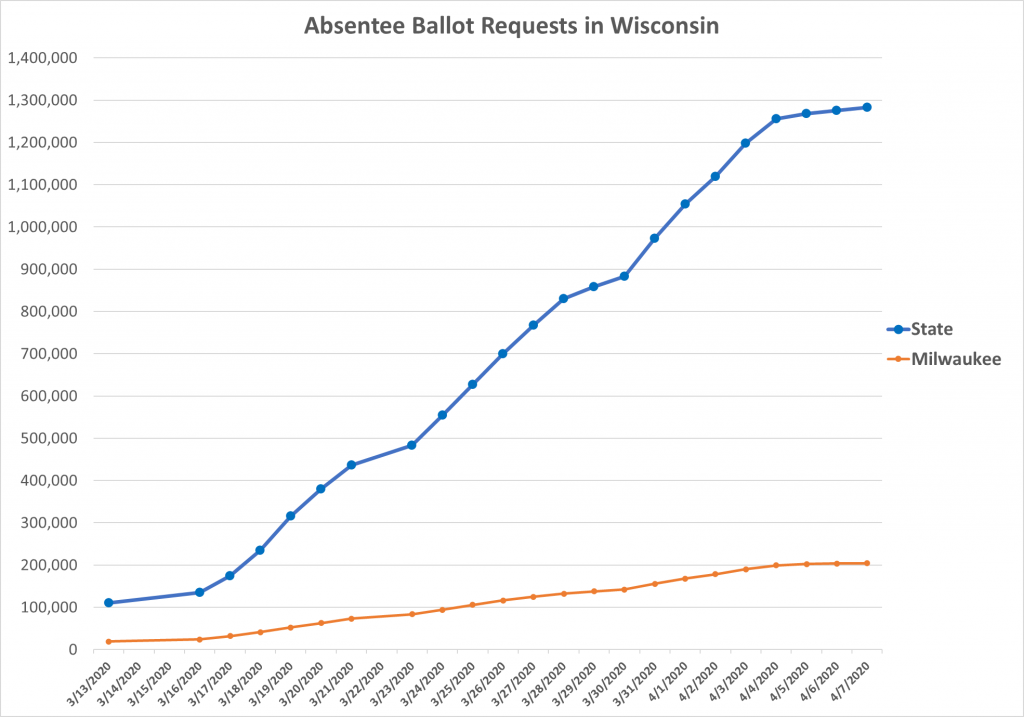

Meanwhile, the month of March saw a steady increase of absentee ballot requests – breaking all past records. In mid March, the requests stood at just over 100,000. But the end, over 1.2 million were requested.

The just under 1.3 million requests topped the 600,000 requests in the 2016 Presidential election. Never before had so many people requested an absentee ballot in the state.

Evers, meanwhile, did get flack from members of his own party for not pushing early to delay the election itself. He finally made a push to delay the election, ordering the legislature into special session the weekend before the April 7th vote, but they refused his proposal. It should be noted that this position from Evers came just days after he insisted April 7th would go ahead. On Monday, after the legislature refused to act, Evers ordered the primary be delayed by Executive Order. The move was rejected by the State Supreme Court and the election went ahead.

Why Didn’t the State Delay?

What didn’t help matters was the partisan split in Government for Wisconsin. The GOP-led legislature showed no interest in delaying the election or moving it to entirely mail-in. Democratic Governor Evers pushed the legislature to authorize sending every voter an absentee ballot, but they balked.

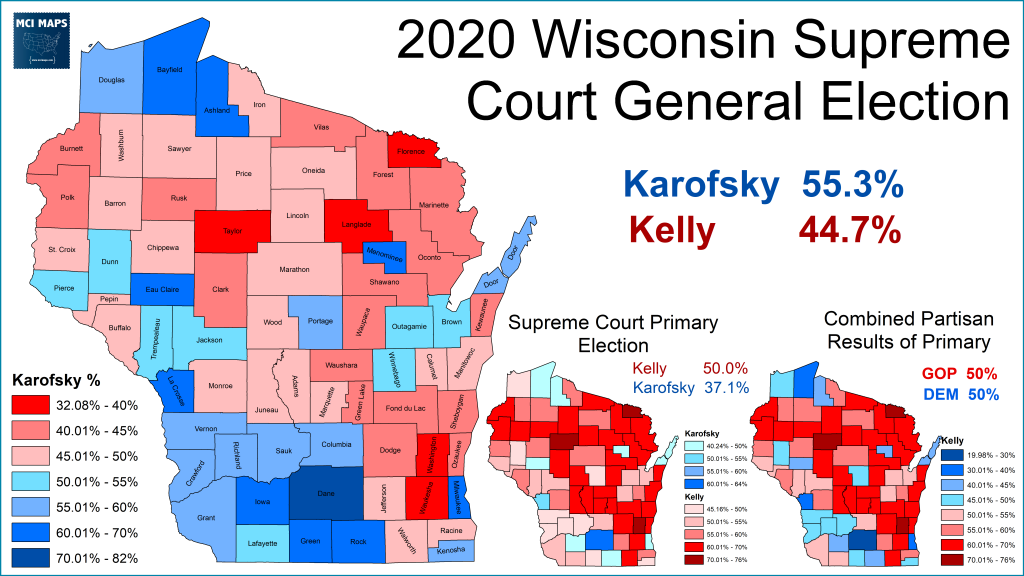

The issue of delaying the election or expanding vote-by-mail was being poisoned by the partisan nature of the April vote; which was going to feature a state Supreme Court race that was being heavily contested by both parties. Scott Walker appointee Daniel Kelly was the GOP-aligned candidate and Dane County Circuit Judge Jill Karofsky was the DEM-aligned candidate. While the race was non-partisan, these elections often become bitter partisan fights due to the cases the Wisconsin Supreme Court must decide. A Democratic win would reduce the GOP majority on the court to 4-3. The race put a partisan lens on any decision regarding voting. The Republicans saw the problems democratic cities were having and figured an April vote would have turnout better aligned for a GOP win. Democrats, meanwhile, were worried that the Supreme Court race could be, in practical effect, be stolen away.

Of course in this instance delaying the election would also have been the public-safety thing to do. But lets not pretend partisanship wasn’t shaping alot of this.

The voting went ahead Tuesday, but absentee ballots were allowed to be returned up until the next Monday (the 13th). They did have to be postmarked by Tuesday, however. Reports from election day showed long lines of people trying to vote. Images of people in masks, trying to maintain distances from other people, dominated the news media.

The election was seen as a tragedy in that it had to carry on as it did. Many cities had seen reductions in voting sites and the images of people risking their health to vote resulted in a great deal of anger. However, the issue faded as the week went on and did not resurface until the 13th, when votes started getting announced.

The Election Results

Counties began counting their results on Monday, April 13th. As counts began to finish, it became clear that Karofsky had a good chance to win the race. As more counties announced, it became clear Kelly had lost and Karofsky had won – and by a solid margin of 10 points.

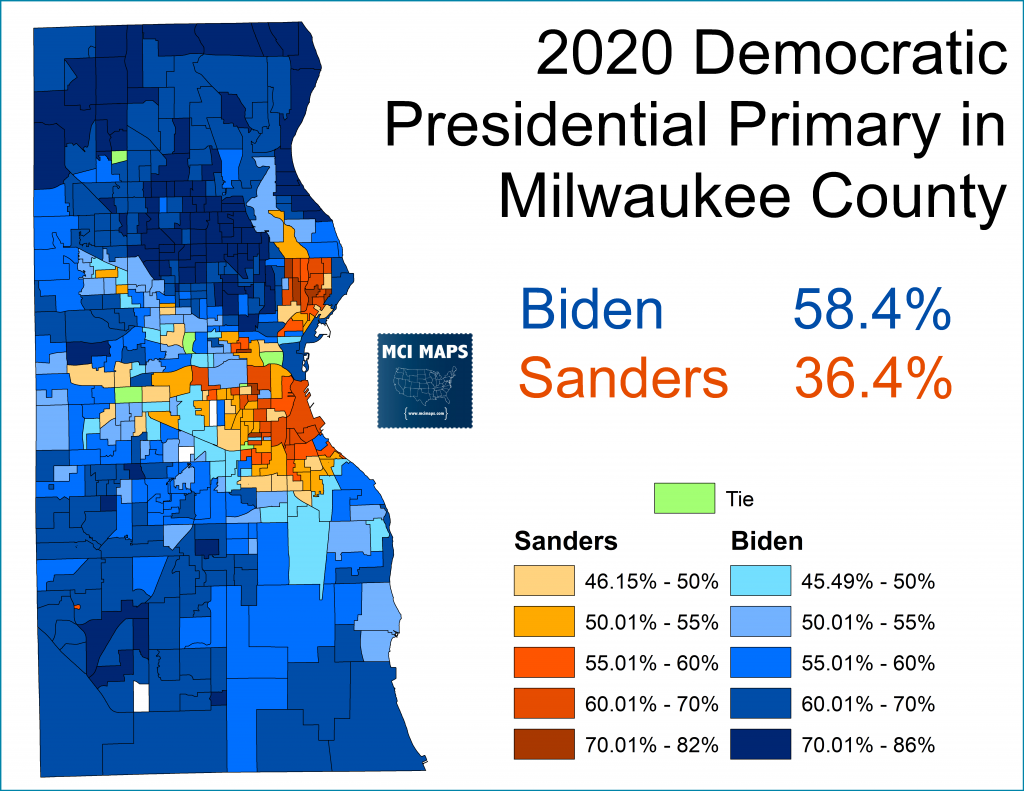

The Democratic Primary received much less attention due to Sanders’ withdraw from the race. It is worth pointing out that all ballots were mailed before the withdraw, so in effect this race took place while there still was a contested Democratic primary. The results of that contest do show that the primary contest was effectively over; as Joe Biden won every county and secured a 30 point margin in the state.

The Effect of the Democratic Primary

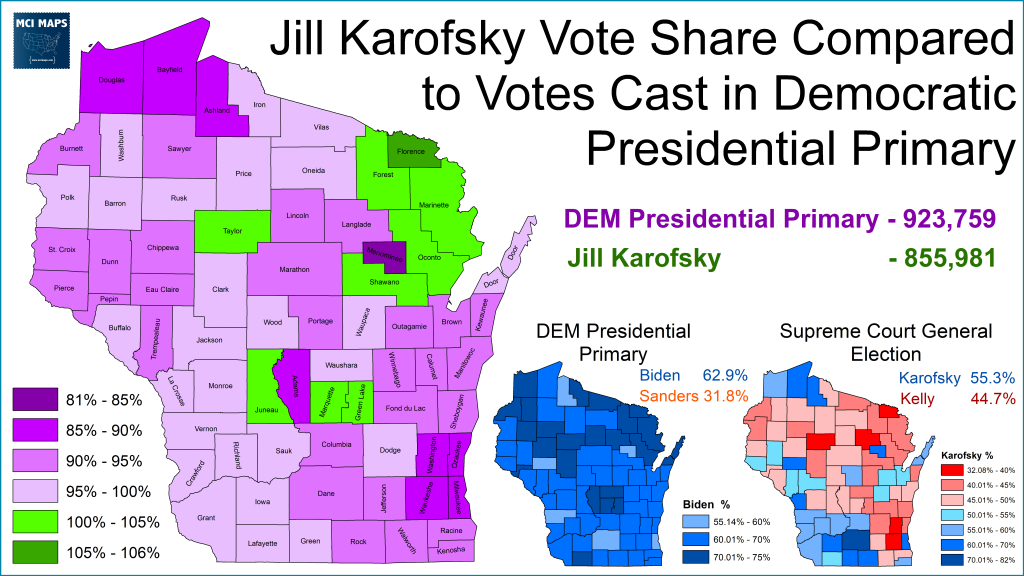

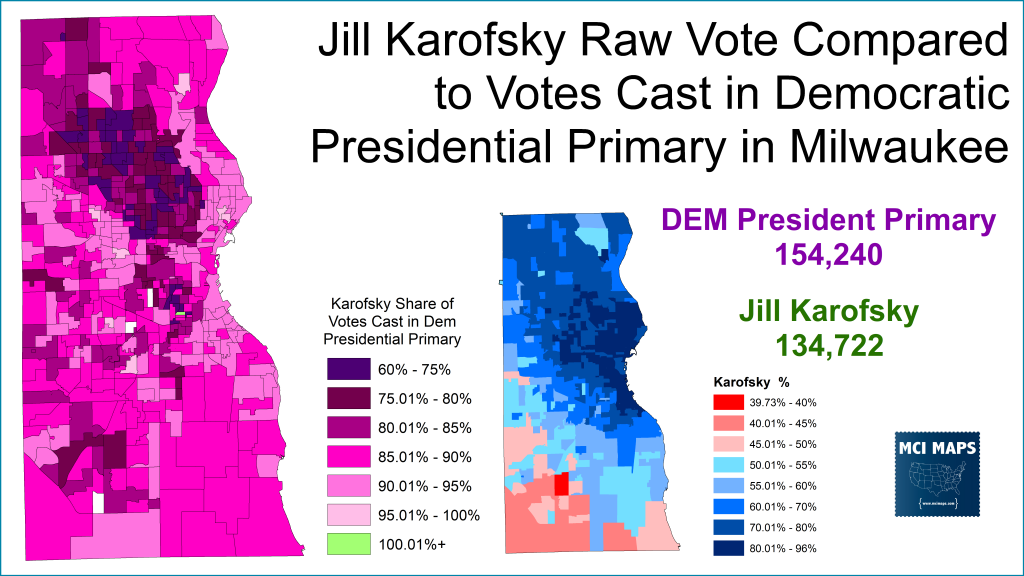

The Democratic primaries presence on the ballot was always believed to be an aid to Karofsky by boosting Democratic turnout. However, the non-partisan nature of the contest makes correlations imperfect – as voters may show up for the primary and skip the Supreme Court race. Karofsky got 70,000 fewer votes than those cast in the Democratic primary. Part of this could be undervotes, while part could be GOP-aligned voters opting to cast ballots in the Democratic primary, which was open to all voters.

There is clear evidence Democratic aligned voters came to vote in the Democratic Primary and either left the Court race blank or didn’t realize Karofsky was the Democratic candidate. The precinct map from Milwaukee County shows Karofsky under-performing the Democratic Primary vote most in the heavily-black precincts in the nort-central portion of the county.

These overwhelmingly black precincts were also some of Biden’s best votes in the Democratic Primary.

It is not uncommon for candidates aligned with a party, but officially on a non-partisan ballot, to under-perform their party metrics in reliable blue or red area. Despite the attention the Supreme Court race got, there will always be partisans who show up for other races and no not know who is who without a D or R listed next to the name.

Turnout Between February and April

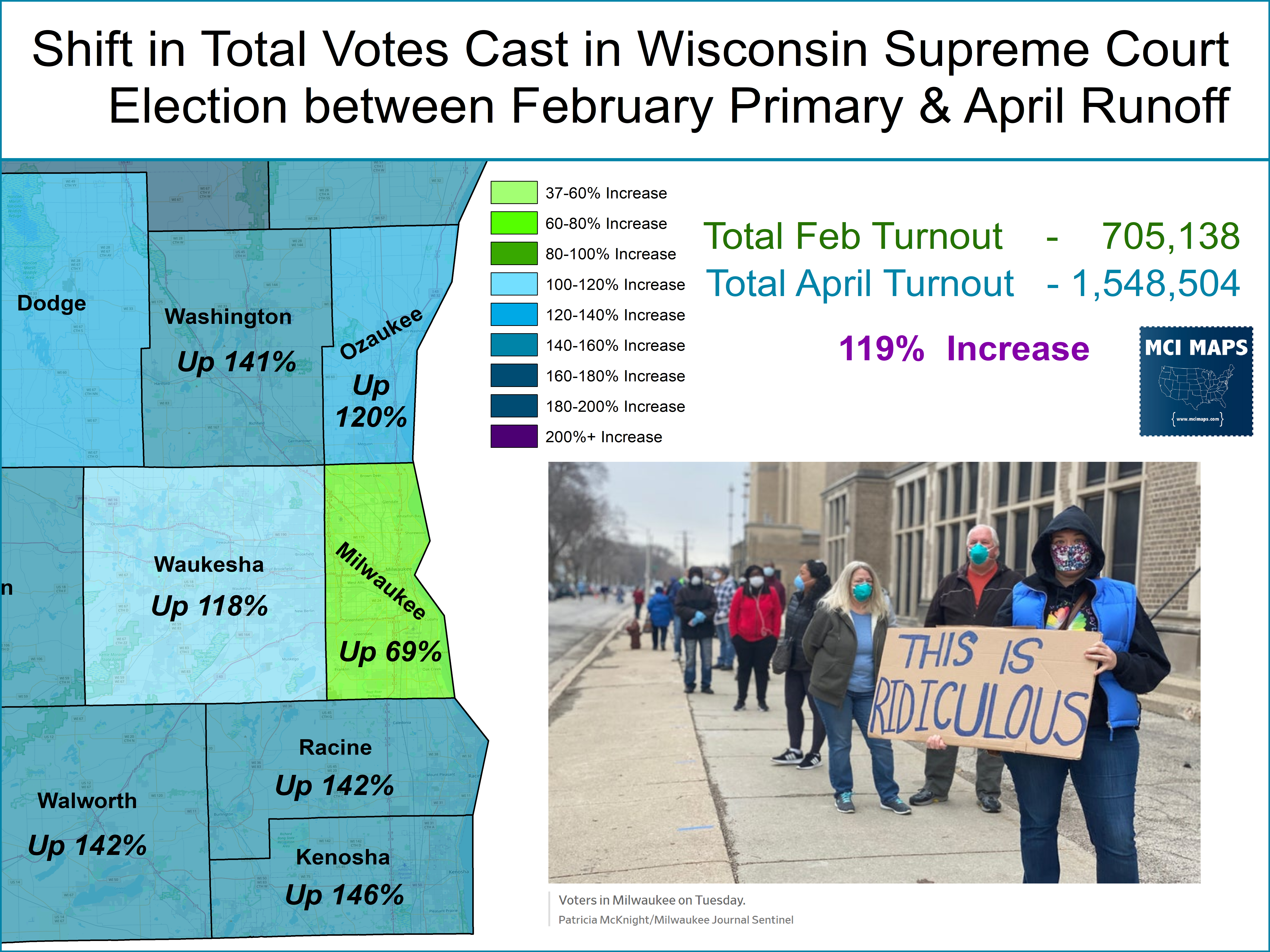

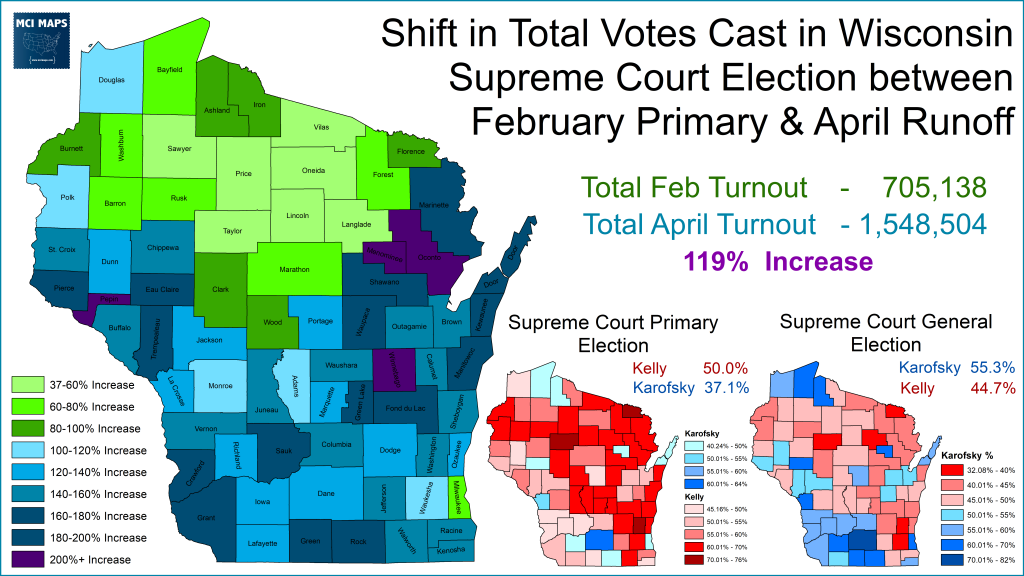

We have an easy way to measure how the COVID-19 chaos effected turnout in Wisconsin. We can look at how turnout shifted between the February spring primaries and the April general/runoffs. Both elections had the supreme court race on the ballot, as well as the scattered municipal elections. February was used to narrow races down to the top-2, while April was used to decide the final winners.

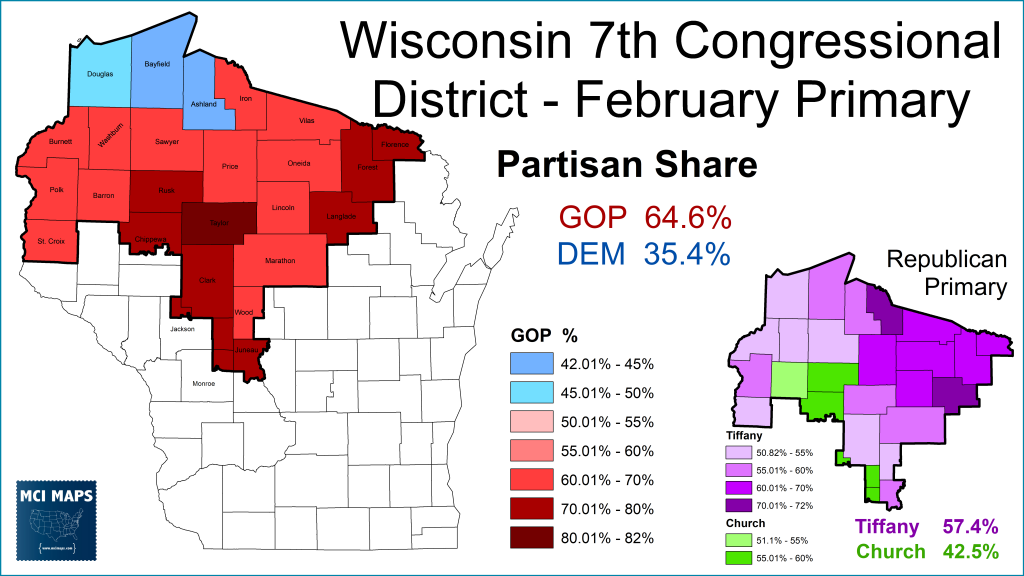

Turnout increased, as expected, by a great deal as the Presidential primary and Supreme Court runoff became the prime movers on the ballot. One big change was that in February, the northern counties had the primaries for the 7th Congressional special election. That race boosted turnout in the Northern counties of the state.

All of the top-turnout counties in February came from the 7th district. However, the district won’t have its general until May. The presence of the 7th district primaries inflated turnout in February for these northern counties; resulting in them having the weakest gains in April.

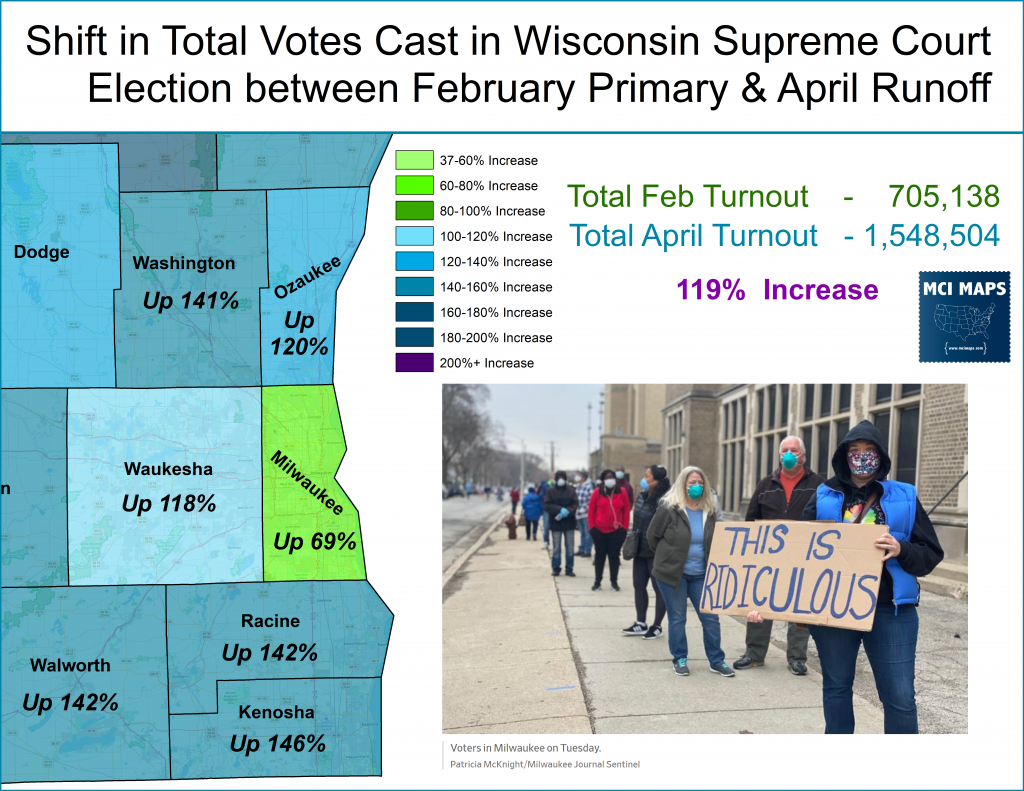

Between February and April, raw votes increased by 119%. The smallest gains largely came from the 7th district – with Milwaukee County being the major exception.

Milwaukee county was the only district not touched by the 7th District to not see at least a doubling in its turnout.

A close look at Milwaukee

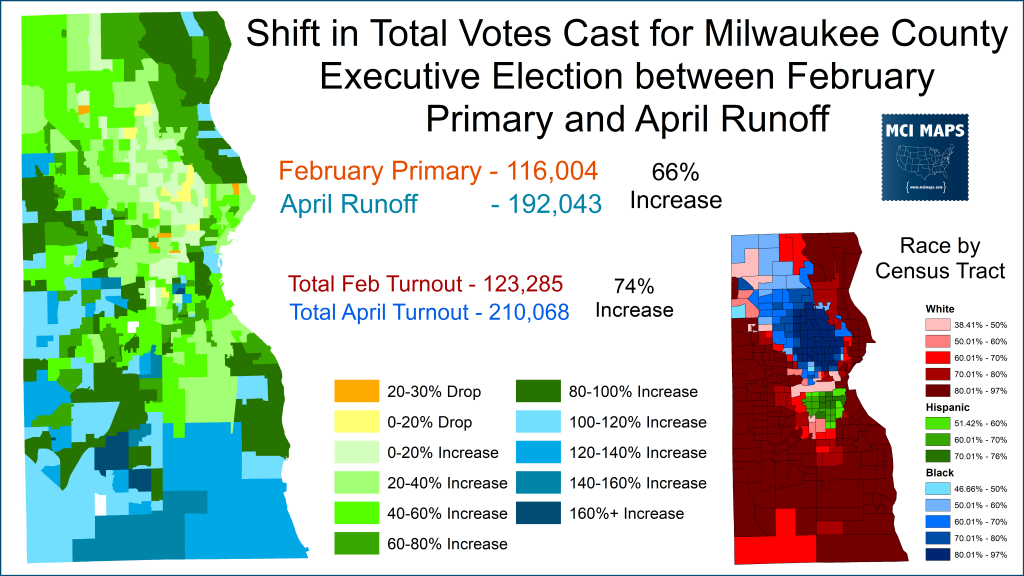

Milwaukee’s weaker gains between February and April shouldn’t be too surprising considering the problems the city and county had in staffing for election day. It appears clear that the closure of polling locations had a serious effect on turnout in the county. Looking at the precinct results reveals more.

Turnout shifts were not equal across the county. The precincts in the heavily-black communities often saw gains under 40%, well below the county’s weak gains overall. This happened amid reports of African-American communities being hit worse by the virus and the fact that Milwaukee City only had 5 voting precincts open on election day.

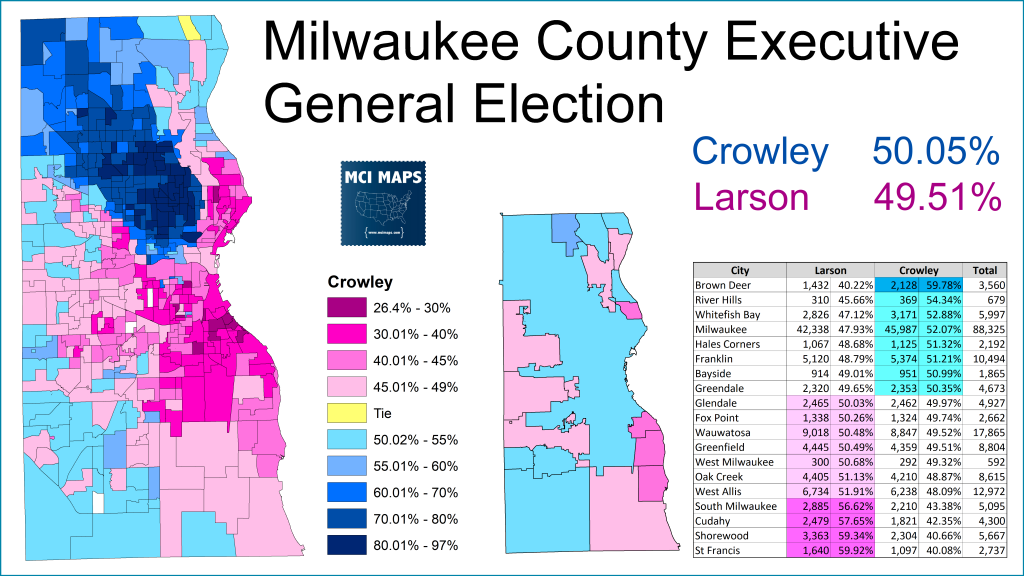

It also cannot be argued that this was due to African-Americans not having a reason to show up – or that they weren’t motivated by any race. The County Executive runoff was a major contest between Democratic State Senator Chris Larson, who represented the white coastal precincts, and State House member David Crowley, who represented part of the African-American communities of Milwaukee. Crowley’s narrow win of just over 1,000 votes makes him the first African-American elected to the position.

Crowley was very strong in the black community, proving they had a candidate to show up for. However, the precinct data shows the black community had the weakest turnout gains between February and April.

In fact, when we look at where voting sites were open (red star), we see that the turnout gains were weakest in the precincts in the gap where no voting sites were close.

Closure of sites was linked to workers indicating they did not feel comfortable working due to virus concerns. Their was a clear disproportionate effect in the Milwaukee City area and it led to a desert of voting locations – which in turn led much weaker turnout gains in some of the most democratic regions of the county and state.

Turnout Comparisons

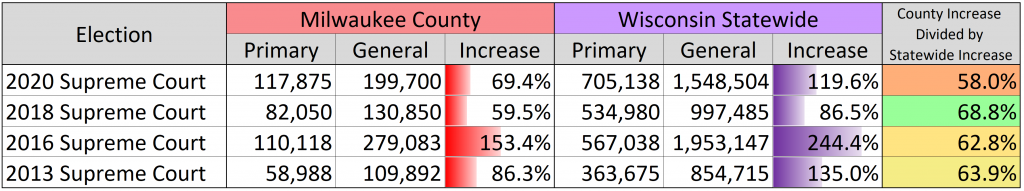

The February to April turnout shows Milwaukee’s gains were weaker than the state overall. To be sure this was COVID-19 driven, I looked at past elections to be sure this wasn’t just the norm. I looked at the last several Supreme Court elections that featured a February primary and April runoff. Each year showed Milwaukee lag the state in turnout increases, however, 2020 was the worst offender.

2020 was not abnormal in respect to Milwaukee having weaker gains than the state, but it did feature the weakest of all – at least since 2013. The other years saw Milwaukee’s turnout increase top 60% of the statewide increase. This time it was only 58%.

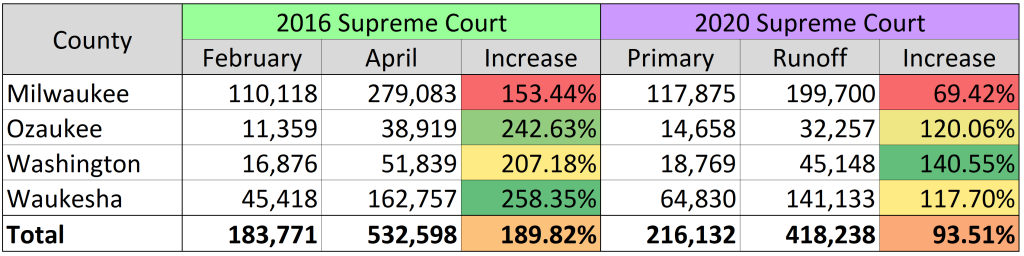

Regionally, the turnout gains were weaker than its surrounding counties. Every county around Milwaukee saw more than a doubling of turnout.

The WOW counties around Milwaukee ranged from 117% to 140% gains. Waukesha saw the weakest increase, and that reflects that fact that the city of Waukesha only had 1 voting location, instead of its normal 13.

Comparing 2016 and 2020 shows Milwaukee always had weaker turnout gains than the WOW counties. However, it was only in the April runoff that Milwaukee managed to not make up over 50% of the votes cast between the combined counties.

What appears clear to me is while Milwaukee always under-performs in the runoffs, it did worse this time; and the culprit is almost surely the voting issues.

Conclusions

Wisconsin’s April election will be remember for the chaos around it. But I fear some of the bigger points about it may be lost. The polling closures did have an effect on turnout – especially in Milwaukee; where closures were the most extreme. Democratic anger over the situation largely evaporated when the Supreme Court race was won. However, the concern about access to voting and safety cannot be forgotten. The precinct data shows not everyone was able to exercise their vote in Wisconsin. Its imperative that not be repeated in upcoming elections.