Today marks the 175th anniversary of Florida’s first elections as a state. Having achieved statehood on March 3rd, 1845; Florida had a short two month campaign for its legislature, Governor, and Congressman. In honor of this anniversary, I want take a brief look at Florida’s push for statehood and the elections that followed.

Editors Note: I have been doing research for a much more expansive analysis of Florida’s territorial politics and statehood debate. Unfortunately, COVID-related shutdowns limited my research capabilities. In the meantime, you can read my look at the very early days of the Florida as part of the US and the story of the first elections to take place in the territory.

The Path to Statehood

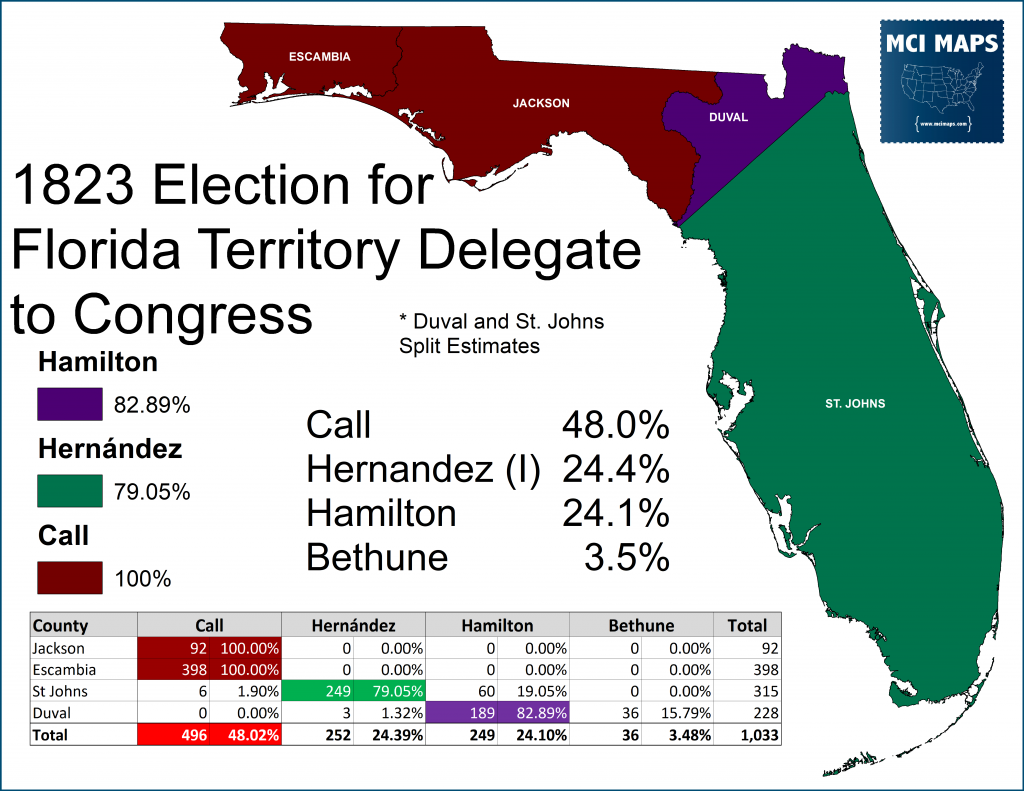

The story of Florida’s path to statehood and the internal debate on the matter is more long and complex than is normally covered. The issue of statehood loomed in the Florida territory for some time in the 1830s. But sectional and national political issues effected opinion on the matter. Eastern Florida was beginning to grow in population size, but most of its residents resented the political power that was concentrated around Middle Florida. Since the territory was established, political power had grown in middle and west Florida via plantations, the land office, and port cities. In 1837, Richard Keith Call was Territorial Governor (a position appointed by the President). Call was based out of Tallahassee and part of the original batch of politicians who arrived with Andrew Jackson in 1822. Early Florida politicians often arose out of the Tallahassee and Pensacola region and where know as “The Nucleus.” The divide in the territory was evident in the first election for Delegate to Congress; where East v West Florida was the theme.

Elections often fell on personality and sectional issues. As a result, East Florida was very much against the push for statehood, as they desired to perhaps break away – something much less likely once statehood was finalized.

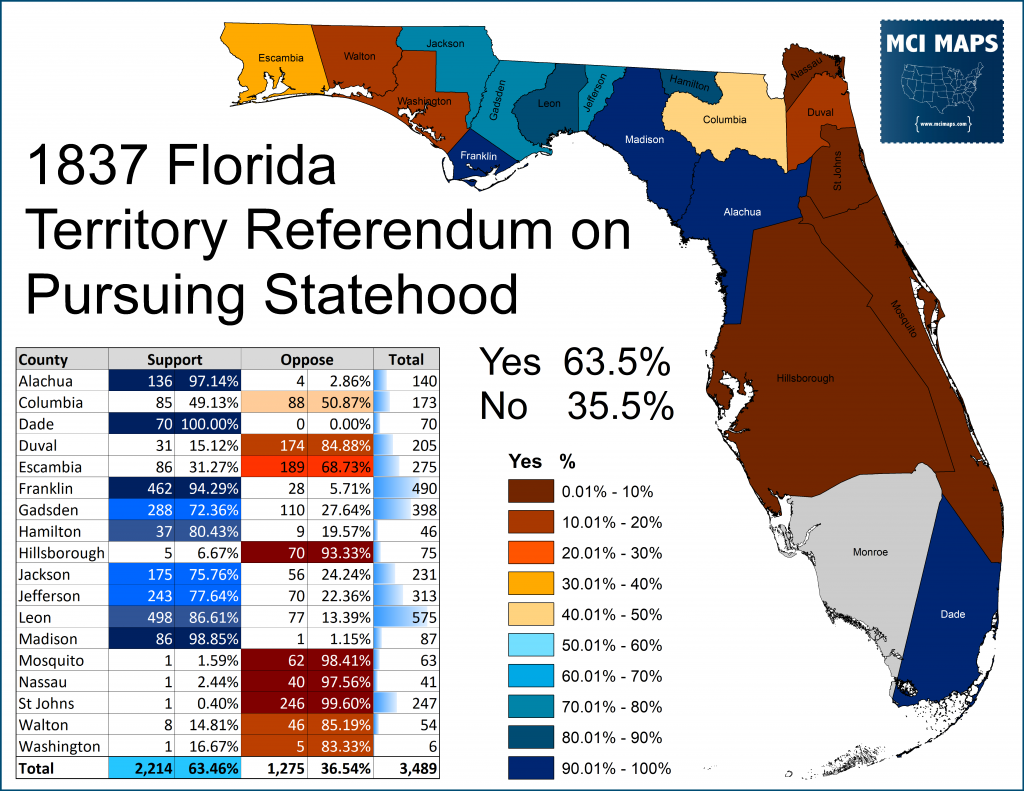

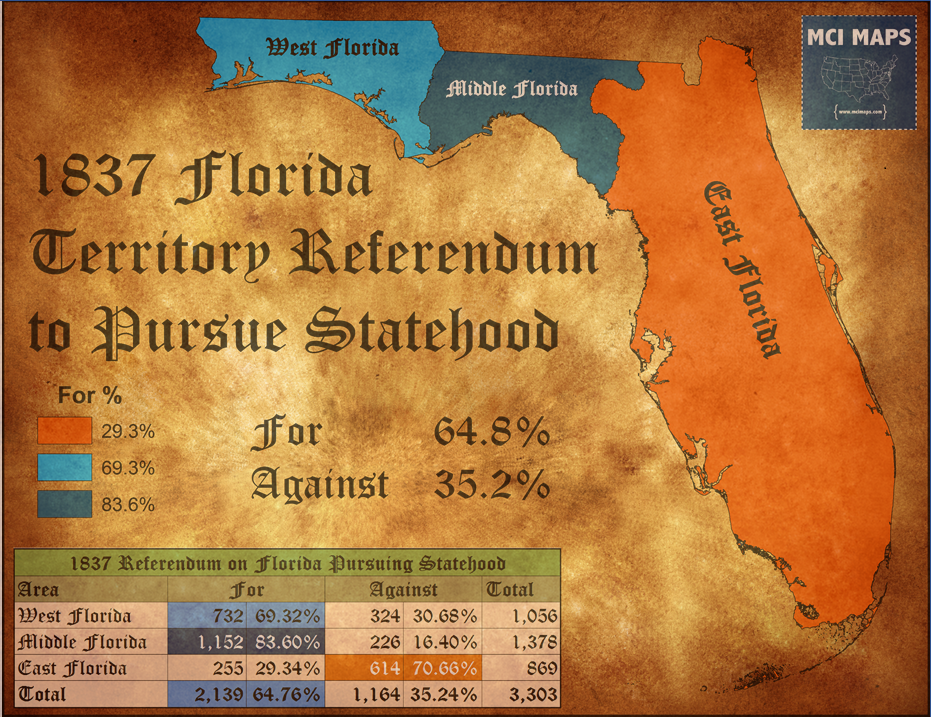

Call pushed for an advisory referendum on the territory perusing statehood in its 1837 elections. The measure passed with a solid 63%, but lost in most East Florida counties.

Middle Florida was overwhelmingly in favor of the push, and while the farthest west end was skeptical, Jackson County favored it.

When the results are broken down by Florida’s three distinct regions, which are divided by the Apalachicola and Suwanee River, both West and Middle Florida backed statehood, but East Florida didn’t.

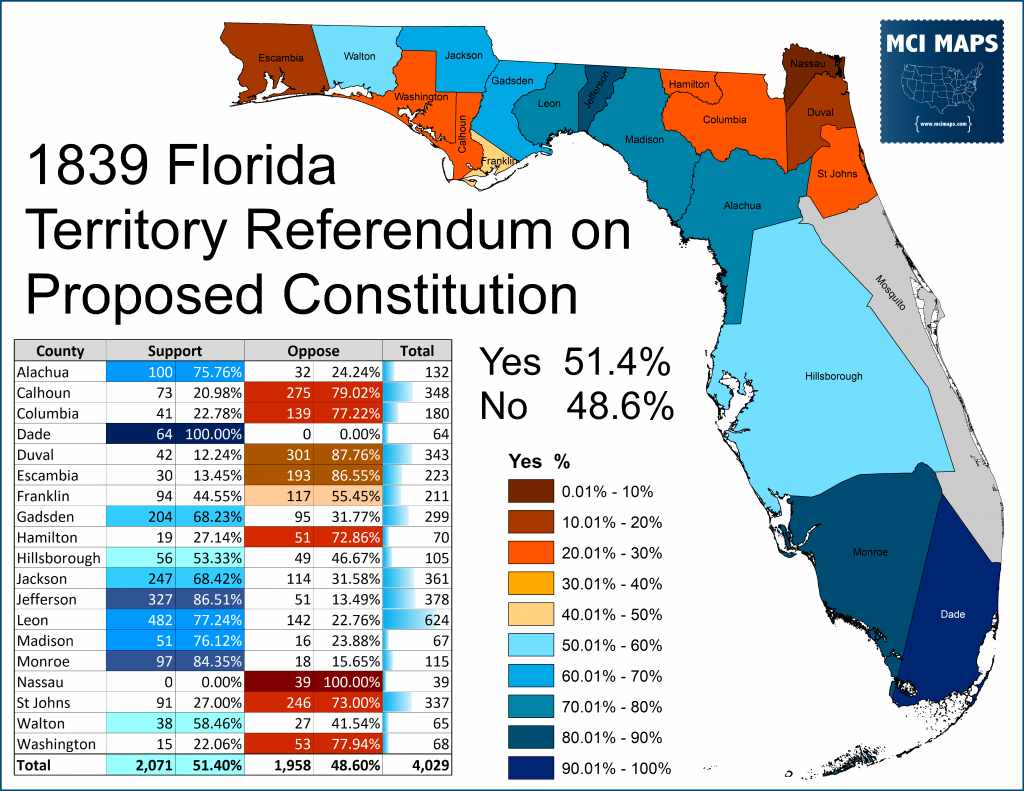

With the passage of the referendum, a convention was called to draft a proposed state constitution. The meeting was held in 1838 at St Joseph, which is now the site of Port St Joe in Gulf County. The convention is widely seen as the site where party politics began to take stronger shape in Florida. Amid the financial Panic of 1837, delegate elections sent an anti-bank majority to the convention. These delegates sought to limit the powers of banks, an institution that most of the longtime Middle Florida politicians were closely tied with. If this reminds you of the battles between Andrew Jackson and the 2nd Bank of the United States, you are not wrong. The convention is where St Augustine politician David Levy broke out on the seen. Levy and other anti-bank delegates elected the Chair and put bank restrictions into the proposed constitution. After the convention, Levy, James Westcott, and Robert Reid would be the major players in a emerging Florida Democratic Party. They won control of the Florida Territorial Council and in 1839 they secured narrow passage of the proposed constitution. Levy represented a small but growing batch of pro-statehood Eastern politicians.

The approval of the constitution put Florida on the path to statehood, but it was not instant. The effects of the Panic of 1837 still loomed large, and Florida’s constitution made it clear it would enter as a slave state. At this point Congress was still in the habit of pairing slave and free state admissions to maintain the “balance of power” in the Senate. In addition, Florida elected Charles Downing in 1839 to be the delegate to Congress for the territory. Downing had been iffy on statehood in the campaign, though the main issues of the campaign focused around the Panic of 37, banking regulations and apportionment debates during the constitutional convention. Downing made no effort to aid Florida’s statehood push in DC and became strongly anti-statehood after his election.

In the meantime, Call was removed as territorial Governor by President Van Buren, and replaced with Reid. Democrats didn’t hold the office for long, however, as William Henry Harrison, who’d been elected as a Whig, reinstated Call during the brief time he was President in 1841. Politicians from the Call-wing of Florida politics began to form what would be the Florida Whig Party, though Call himself tried to stay above party politics – even though his politics put him much more in the Whig camp.

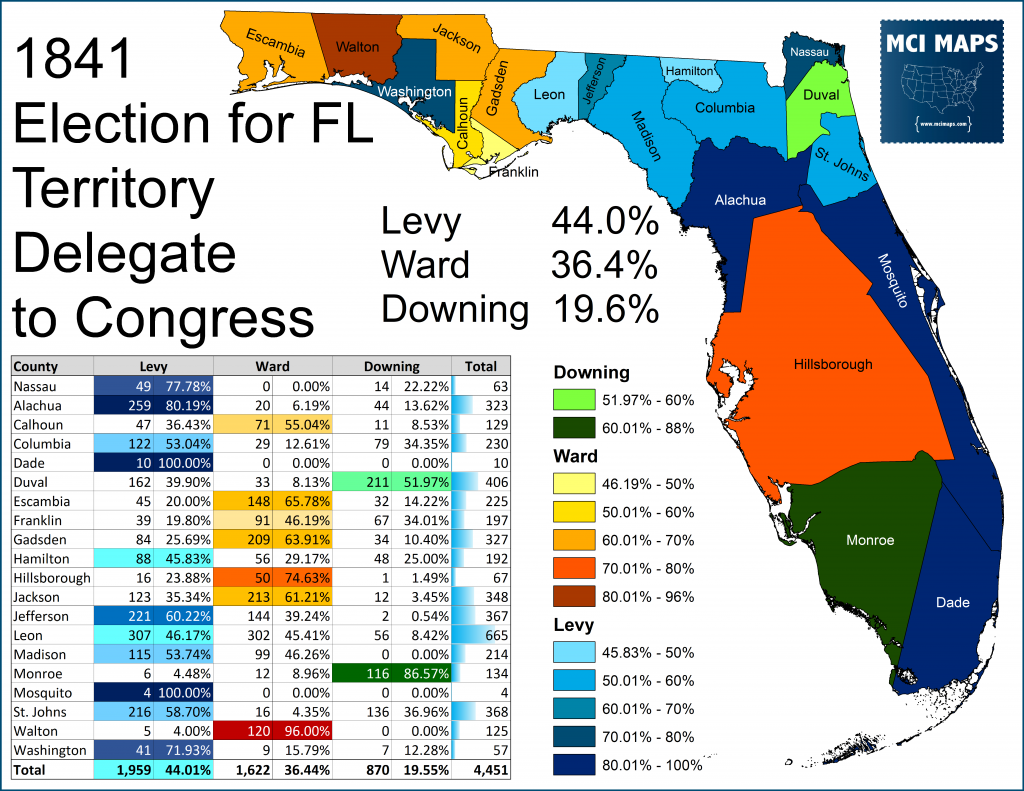

The Territorial Delegate election of 1841 was instrumental in Florida’s continued path to statehood. Downing, having alienated almost everyone by this point, lost in a landslide in his re-election. Whigs wanted a fresh candidate and picked George Ward, a pro-bank politician. Downing, who was closer to the Whigs on issues than the Democrats, refused to bow out and stayed in the race. The split in the Whig-aligned vote allowed David Levy to win the delegate race.

Levy would go to DC and be a major advocate for Florida statehood.

Politics in the territory got more chaotic. As the anti-bank, Democrat-controlled territorial legislature saw its reforms do little to improve the economic situation in the territory (really nothing was going to, this was a major financial crisis like the Great Depression) – Whigs saw an opening and began to soften their stance on bank issues. Whigs also began to better organize and their slate of candidates won control of the territorial legislature in 1842.

In addition to electing a Whig legislature in 1842 (with more wins in 1843), the voters also elected (possibly without knowing) an anti-statehood legislature. Many members expressed concern about the burden of statehood during the economically uncertain times and east Florida Whigs pushed for division of the territory. In 1823, the council passed a resolution calling for voters to again approve the St Joseph Constitution in a new referendum, or a new constitution be drafted. In 1844, the council passed a resolution asking Congress to divide the state along the Suwanee River. Nothing came of either push from Governor Call or Congress

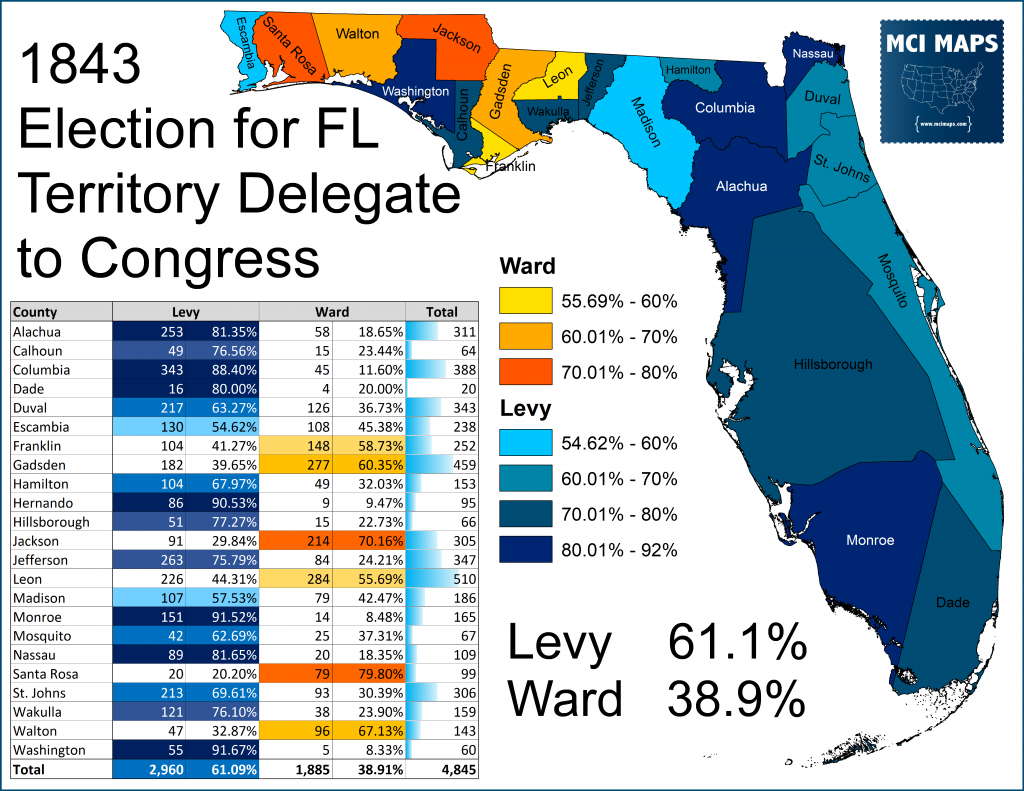

Meanwhile, David Levy ramped up the push for statehood, which was aided by the Iowa territory appearing near ready as well. Iowa coming in as a free state would necessitate a slave state coming in to maintain the balance. Levy latched onto this and won re-election as delegate in in 1843.

Levy also campaigned to get a pro-statehood democratic majority in the legislative council in the 1844 elections, which succeeded. Levy and the Democrats made statehood a major push and brought East Florida more around on the issue. Call’s term as Governor expired in July of 1844 and President Tyler replaced him with Democrat John Branch.

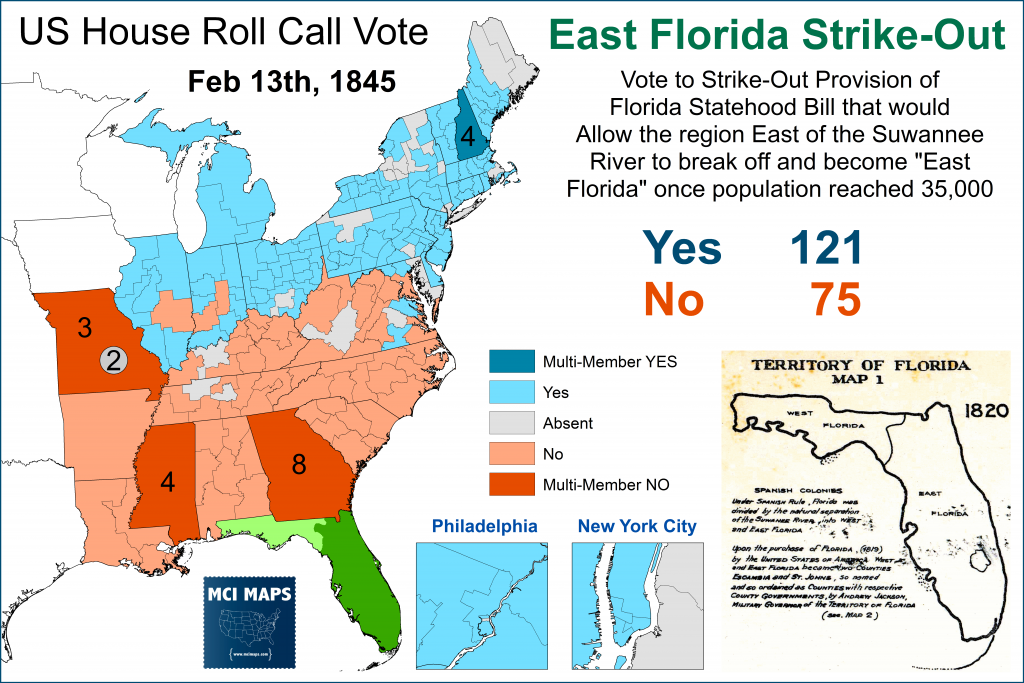

The push for Florida statehood took on a fever pitch in Congress in January of 1845. Both Iowa and Florida were expressing statehood desires and pairing the two together was a must. Weeks of back and forth fights by abolitionists and pro-slavery members of Congress began. Northern members of Congress took exception to the 1838 Constitution’s provision that forbade the legislature from emancipating slaves, and gave the legislature the authority to restrict the emigration of freed blacks into the state. Levy fiercely defended the provisions. Levy was an ardent defender of slavery and would go on to be one of the pro-slavery radical “Fire Eaters” during the 1850s. Levy also supported a provision in the original statehood bill to split the territory into East and West. This was not only due to Levy’s position as an East Floridian, but a pro-slavery gambit to create two slave states – with four senators. This proposal was eventually stripped from the statehood bill, falling on sectional lines.

Statehood would come on March 3rd, when Iowa and Florida were paired together in the same bill; which was signed by President Tyler. With the admission, elections for state organization were set for May 26th, 1845.

The 1845 Elections

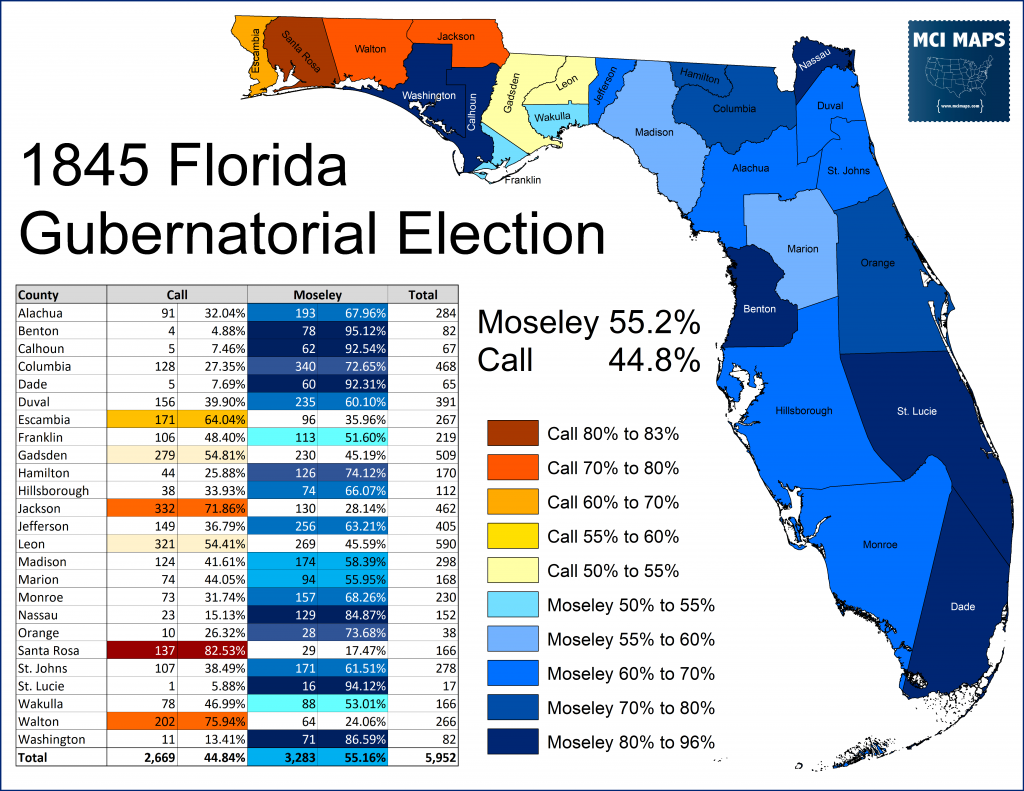

Statehood hit fast in Florida, something the Democrats were ready for but the Whigs were not. Elections were to be held on May 26th for Governor, legislature, and Congress.

Democrats met on April 14th in Madison to elect their statewide slate. Levy ran for the Congressional seat, but he made it clear he desired to be a Senator if the legislature went into Democratic hands. The Democrats selected William Moseley of Leon County to be the nominee for Governor. Moseley had been politically involved as a member of the territorial council and active Democrat, but his unanimous win at the party meeting is somewhat striking; as it would seem reasonable many Democrats would have liked the job. The implication I get is that this was heavily influenced by Levy, which controlled much of the party and would be the main campaigner in 1845. Moseley was a non-controversial pick who could slide into office from straight-ticket voting Democrats. Levy would lead the charge in the election.

The Whigs struggled to organize. They originally approached a planter from Jefferson County, William Bailey, to be their nominee; but Bailey rejected the offer. The Whig members of the territorial council then pushed Joseph Lancaster of Duval County to be the Congressional candidate, but other eastern county committees insisted on Benjamin Putnam of St Johns. The disorganization continued after the Democrats held their meeting and in a desperate move to get on the same page, the Leon, Gadsden, and Whig committees met to try and form a compromise ticket. The gathering met in Leon County and selected Richard Keith Call for Governor; relying on his years in the state and strong name ID. They then agreed on Putnam as the nominee for Congress to placate the east.

The compromise Whig ticket worked and the campaign began. Whigs stood at a tremendous disadvantage, however, as Democrats were better organized and more Florida papers were pro-Democrat than pro-Whig by this point. Call and Levy were the main campaigners for each side; as neither Putnam or Moseley were well known. Call and Levy had been clashing for years, and went after each-other on the campaign trail. Call resented Levy’s fierce adherence to party politics and Levy saw Call as a representative from the old Middle Florida “Nucleus.” It should be noted, though, that for all the attacks on Call, he wasn’t as much of a partisan as Levy was. When Call had been territorial Governor, he did not use the office to build up the Whig Party, but Levy and the Democrats used the the times that Reid and Branch were Governors to build the party. Call likewise campaigned on the idea of being above party politics and guiding the new state. Levy and the Democrats, however, campaigned much more partisan and went after the Whigs for old ties to banks and the upper-class planters.

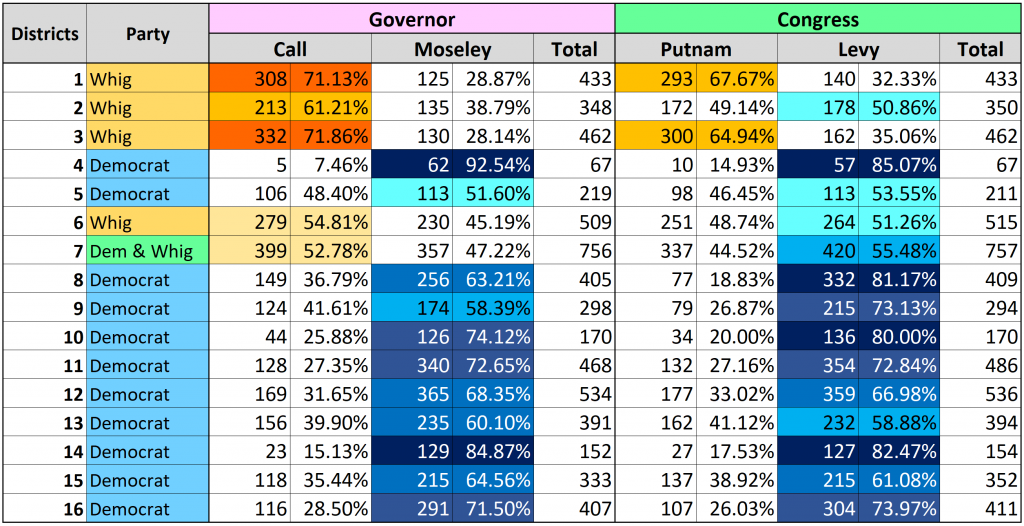

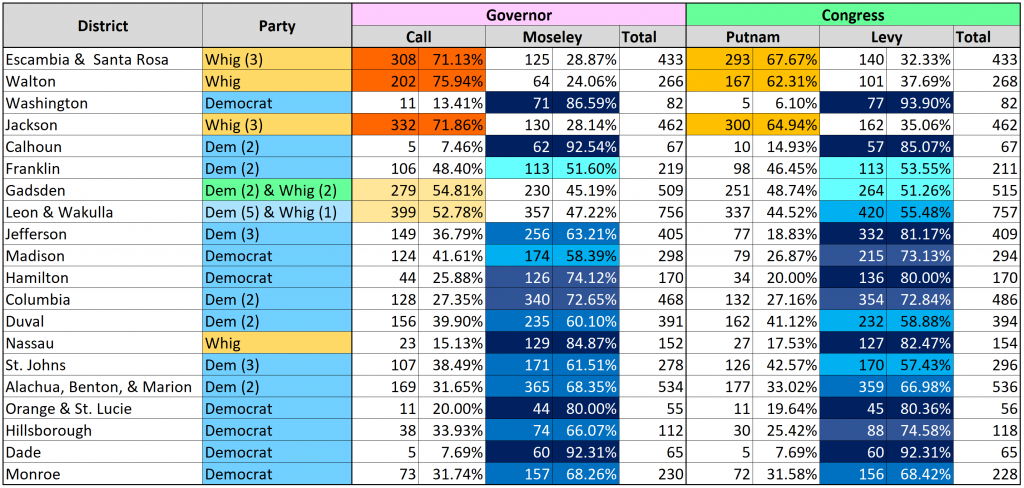

In the end, the Democratic campaign and infrastructure won it for them. Moseley bested Call by 10%.

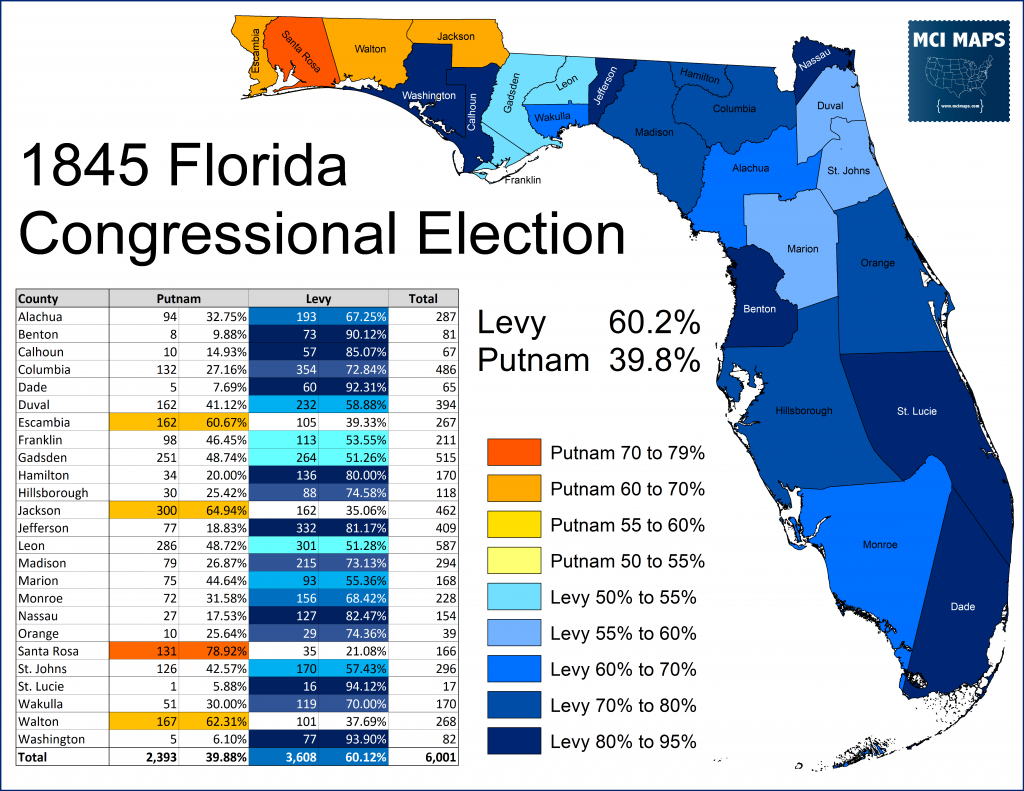

Levy won by 20%, taking Gadsden and Leon Counties as well, leaving only the far west counties for the Whigs.

Levy readily took credit for the wins.

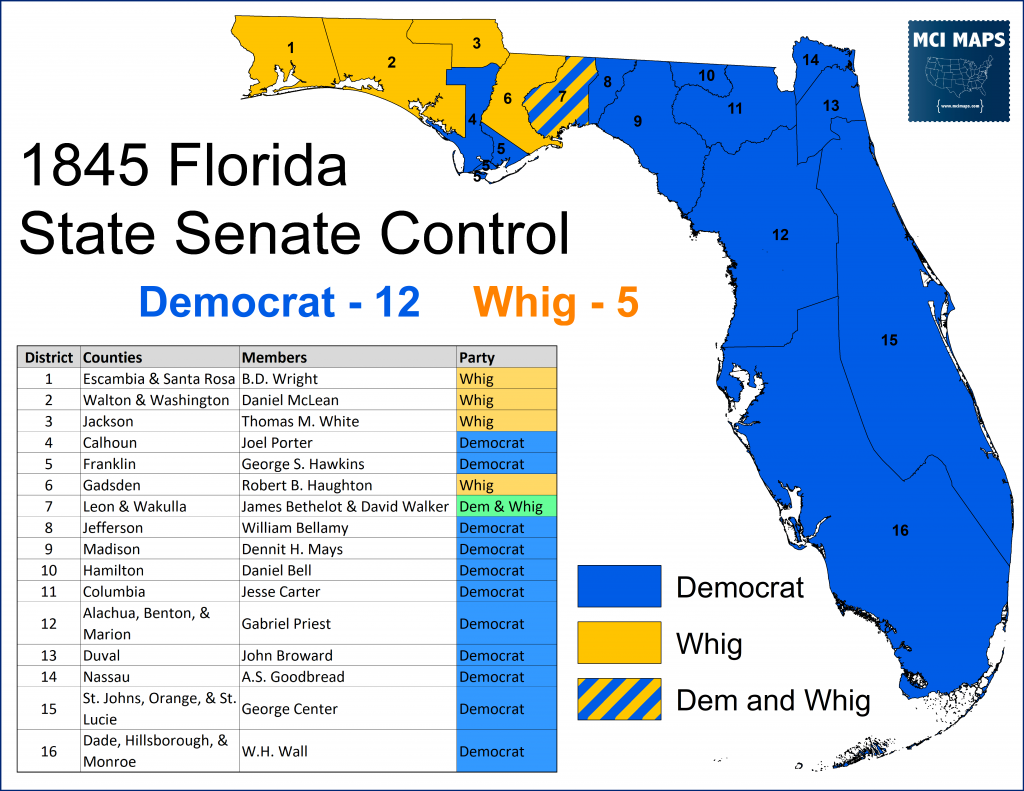

The elections for state legislature saw solid Democratic majorities elected. The State Senate elections broke down to 12 Democrats and just 5 Whigs. Most district elected just one member, but the Leon/Wakulla district was apportioned two Senators, which were split between the Whigs and Democrats.

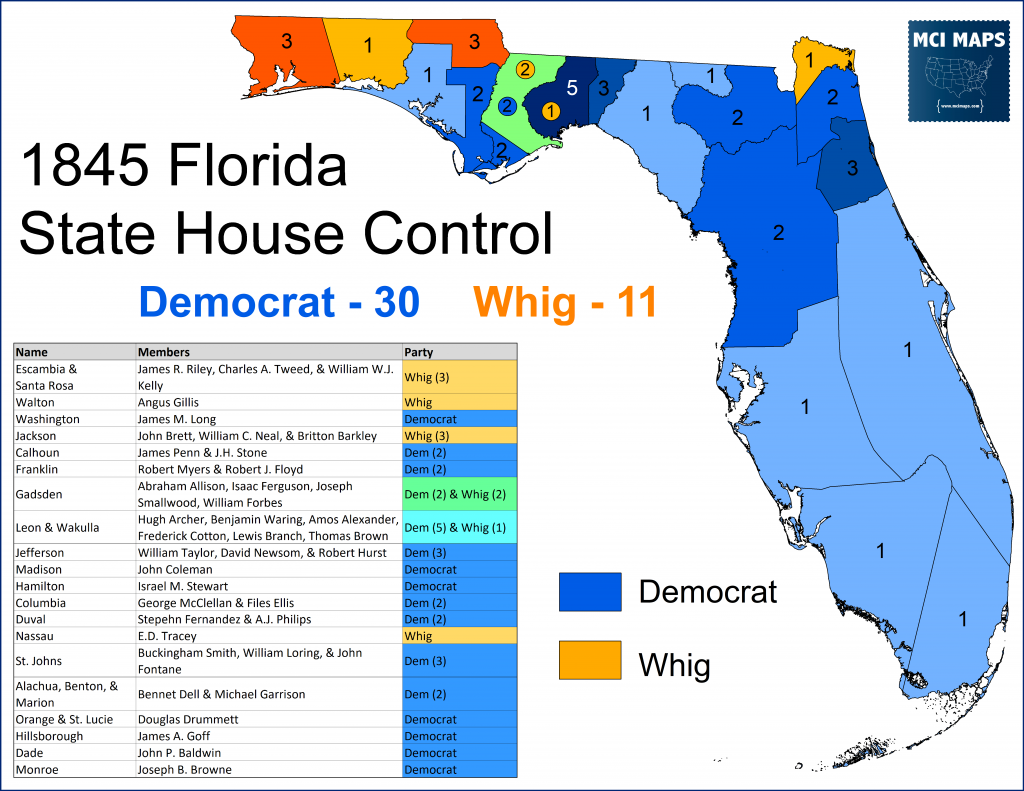

The state house districts featured many more multi-member districts. Most seats elected straight-ticket delegations, but the Gadsden/Leon/Wakulla area split its tickets. Gadsden sent 2 Whigs and 2 Democrats, while Leon sent 5 Democrats and just 1 Whig. The totals were 30 Democrats to just 11 Whigs.

Looking at how the statewide races broke down by legislative district reveal voters largely voted straight tickets. Seats won by Whig State Senators were the more Whig-friendly seats for Congress and Governor.

The same straight-ticket voting happened in the lower chamber. Even Gadsden’s split delegation reflects the fact the county voted for Call but also for Levy.

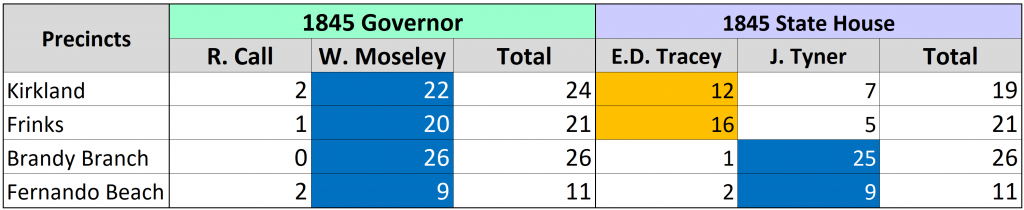

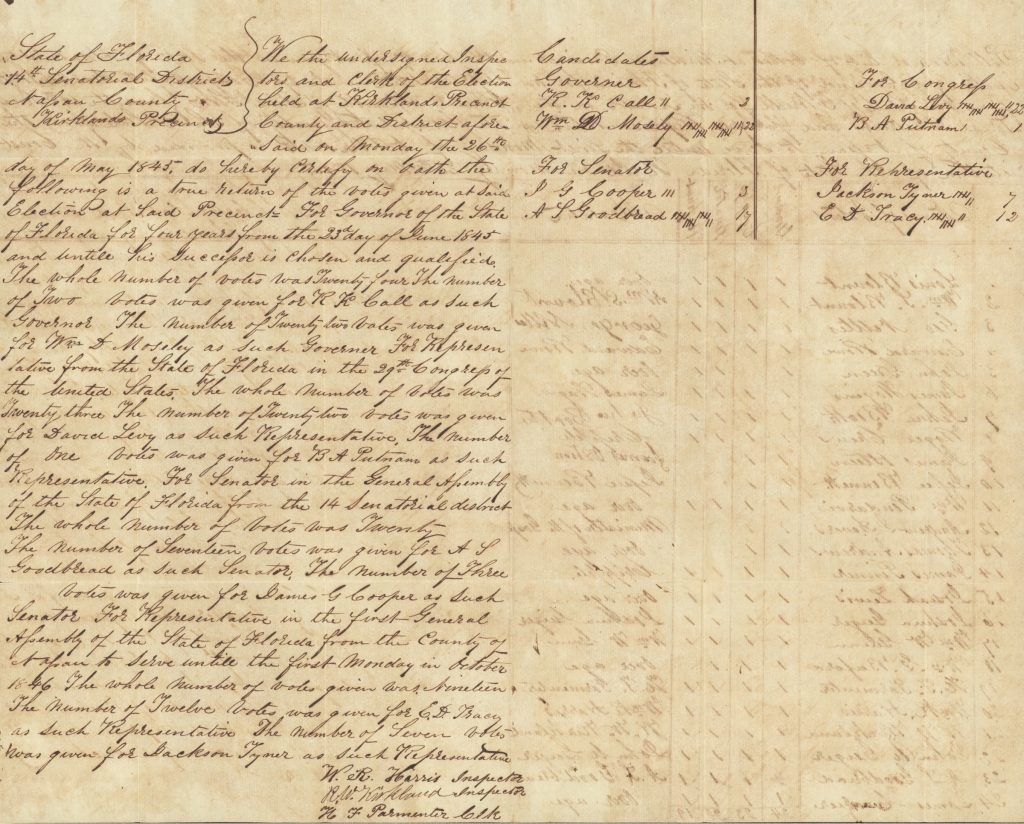

The must stunning example of ticket splitting was in the Nassau county house seat. Whig Erasmus Darwin Tracey won the seat despite it voting over 80% for the Democratic candidates for Congress and Governor; as well as electing a Democratic State Senator. We don’t have complete precinct data, but the few available show some precincts voting straight-ticket, while others saw massive splits.

Tracey would be a major figure in Nassau and Florida politics. He’d eventually be elected to the State Senate and becoming Senate President when Whigs took control of the chamber in the 1848 elections.

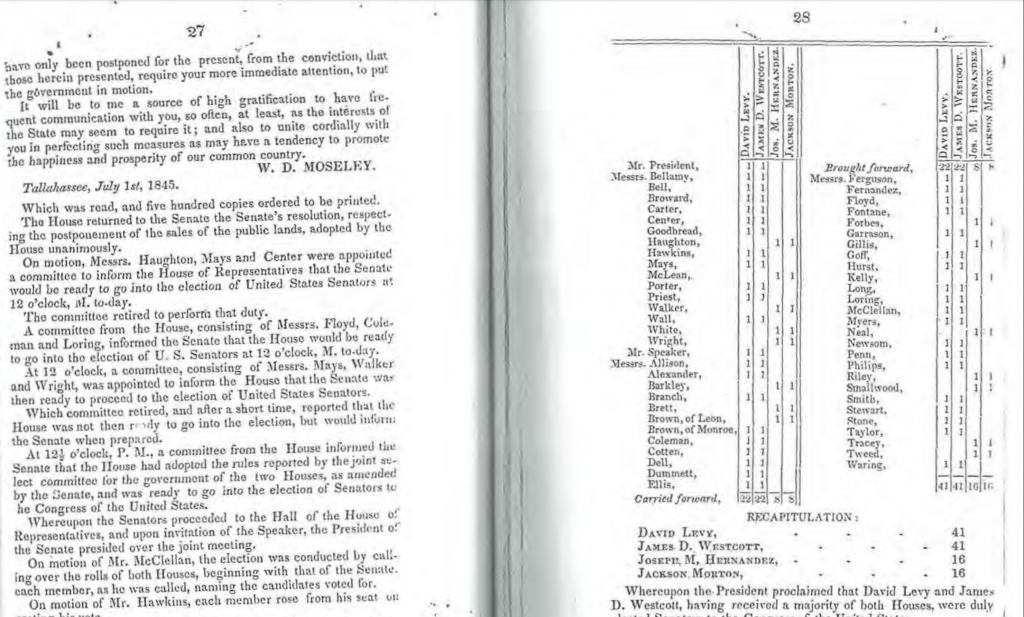

When the legislature convened to elect its US Senators, the results fell directly on party loyalty lines. Democrats David Levy and James Westcott, both original founders of the Florida Democratic Party, were elected as Senators with 41 votes each; all Democrats except Dade’s member, who was absent. Levy’s elevation made him the first Jewish person elected to the United States Senate.

Levy’s election to the US Senate would trigger a special election for his Congressional Seat. The race would be scheduled for October and would feature the first of many, many, many controversial elections and recounts in the state.

The Chaotic Special Election

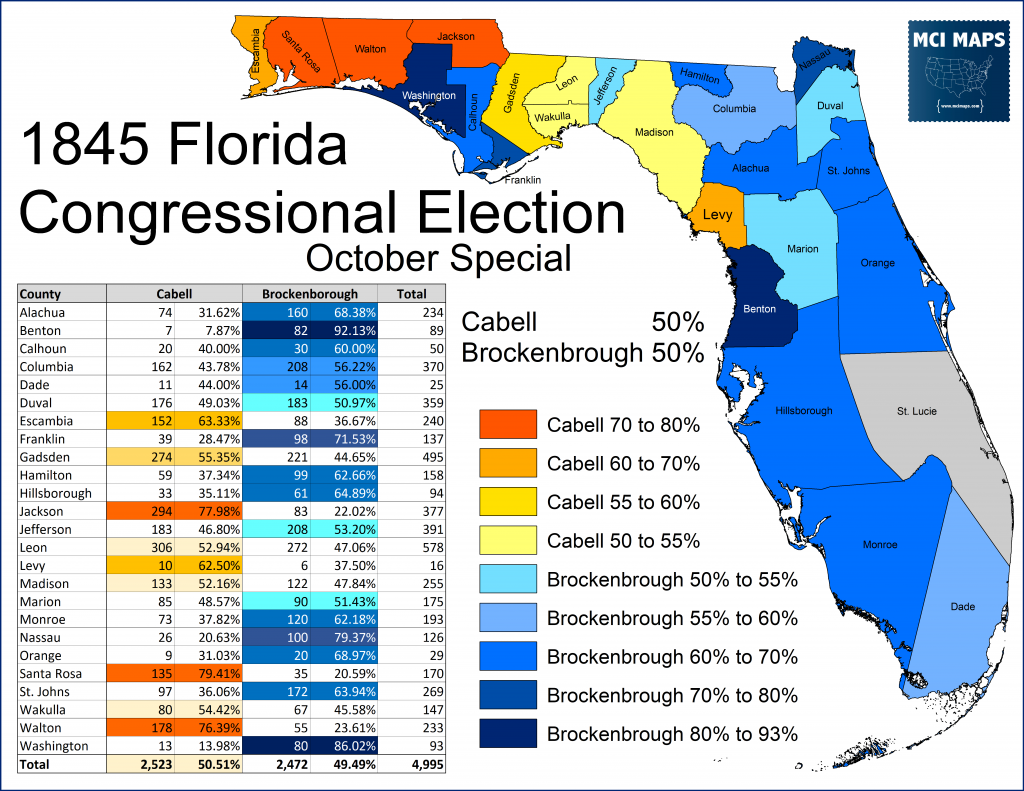

The electoral landslide of May gave the Whig Party little hope for the special election to follow. A sentiment emerged that the Whigs might just sit the race out. However, Edward Cabell, a 29 year old lawyer, opted to make the challenge. Cabell was actually a member of the St Joseph convention and had a reputation as a dynamic speaker. His selection was perfect for the Whigs, as it would be impossible to tie him to old bank controversies or the old “Nucleus” guard. The Democrats nominated William Brockenbrough, a former member of the Territorial Legislature and District Attorney. Brockenbrough also had past ties to Whigs, which caused some tension with party regulars but was also aimed to be bipartisan.

Cabell is widely credited with rejuvenating the Whig Party, running a strong campaign and giving impassioned speeches. Brockenbrough was considered to be a poor campaigner. When returns began to come in, the race was extremely close. It wasn’t until the 30 day deadline for returns came and went that Cabell was declared the winner by the slimmest of margins.

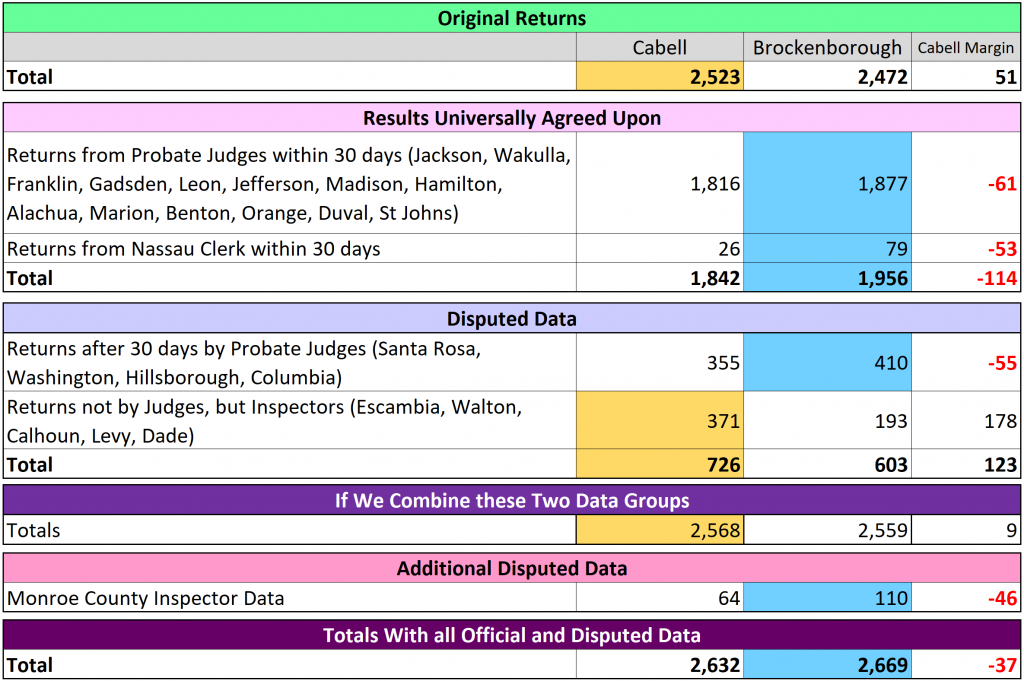

Cabell’s will was approved by Governor Moseley and he took his seat in Congress, but Brockenbrough and his backers insisted the wrong man had won. Their argument hinged on which returns should have been accepted and included in the vote totals. Indeed in a young state, covering huge swaths of land, the vote returns could take great deals of time. There was also apparently confusion over who would oversee elections in each county; clerks, probate judges, or inspectors. Election returns also arrived after the 30 day deadline. The case was heard by the US House Committee on Elections, and the arguments and findings are in this link. To summarize a very complex situation, the vote totals could break down the following ways.

The Brockenbrough argument was that if all returns were counted, he’d have won. He did have a point, in that Cabell only won if the “Disputed Data” column was included. But including those returns meant Monroe’s should be included as well (as the circumstances were similar). That would have left Brockenbrough with a 37 vote lead. Notice that the original returns are slightly different, and also don’t match the county returns from the map. Nothing adds up right. While fraud or manipulation is always the quick answer (and we can’t rule anything out) – another common theme from this time is error. Results were often written in cursive long-form and mistakes in totaling is not uncommon.

Like any election, these small errors mean little when a race isn’t close. However, when its neck-and-neck, suddenly its a big deal.

The US House voted to seat Brockenbrough and remove Cabell. The vote largely fell on party lines, and Democrats controlled the chamber. There is an argument Brockenbrough may have been right; but the many variables mean its hard to know who really won that vote. The seat went to the Democrat in January of 1846, just three months into Cabell’s term.

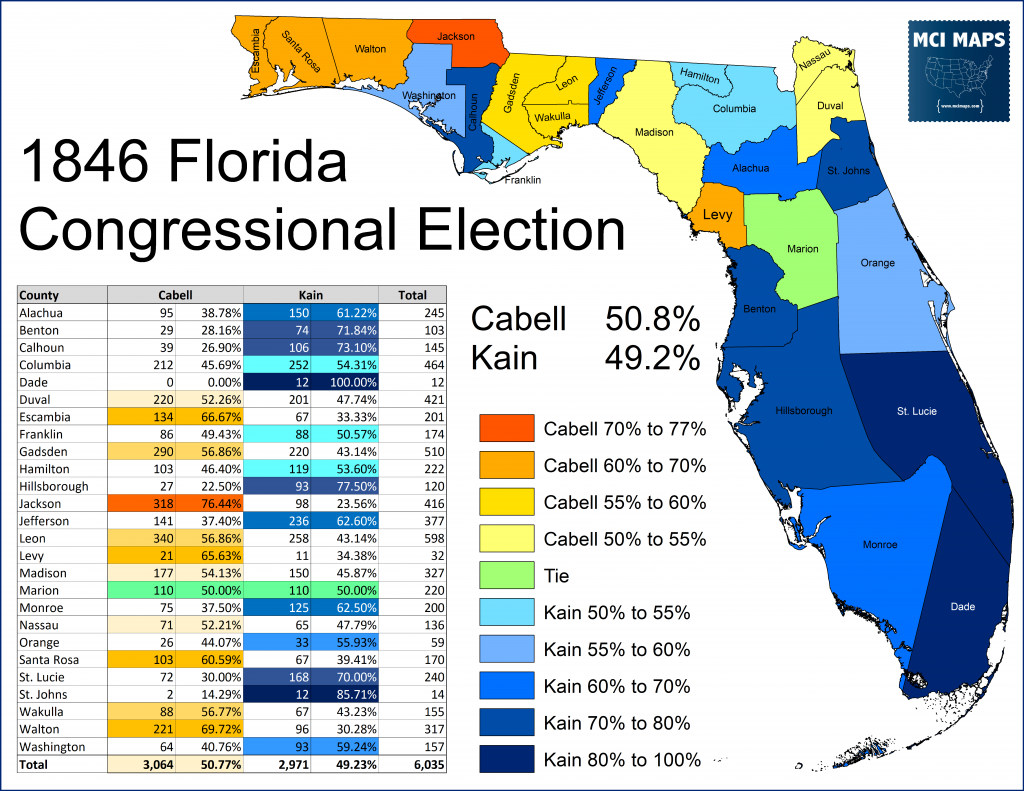

The bait and switch did wonders for the Whigs and Cabell. The situation made Cabell a martyr and gave his party something to rally around in the 1846 elections. Cabell made it clear he would seek a rematch with Brockenbrough. Democrats didn’t want to risk the issue and denied Brockenbrough renomination at their convention. They instead nominated State Senator William Kain, of Apalachicola. Cabell would go on to secure a narrow, but more solid win.

Cabell’s win also came with Whigs picking up seats in the state legislature and put the party on a path to flip the chambers in 1848. The chaos of the special election and the energy of the young Cabell had helped turn Whig fortunes around, and set Florida up to be a two-party state for the next several years.