The Curious Case of Utah

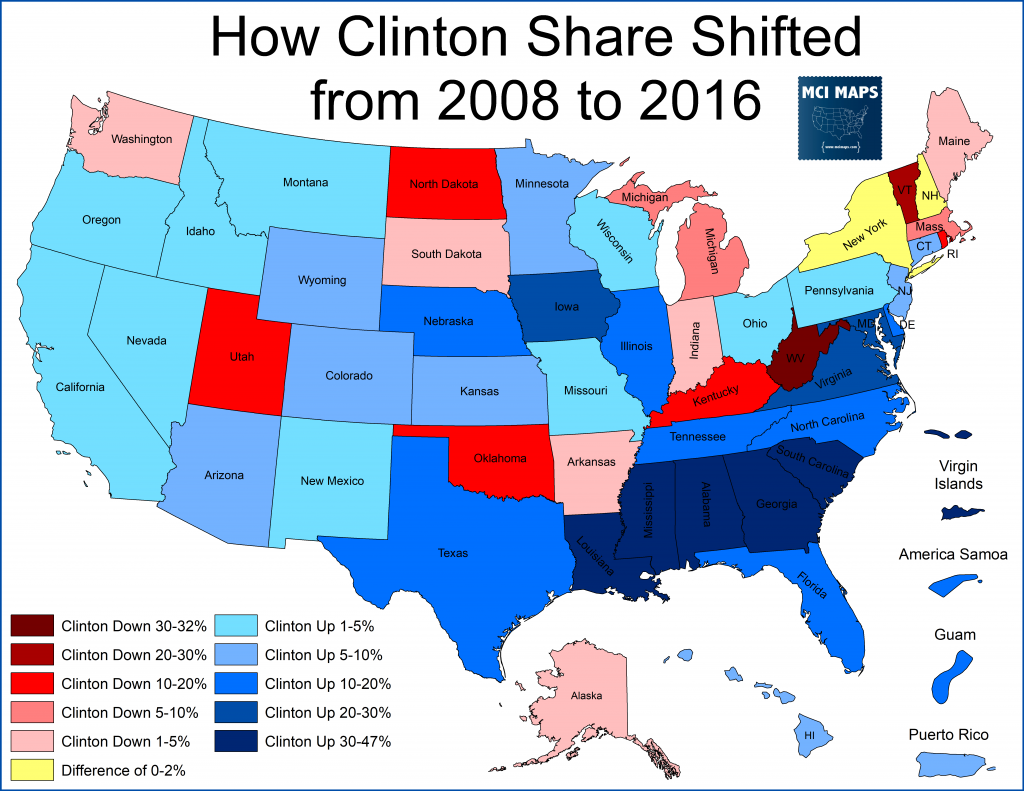

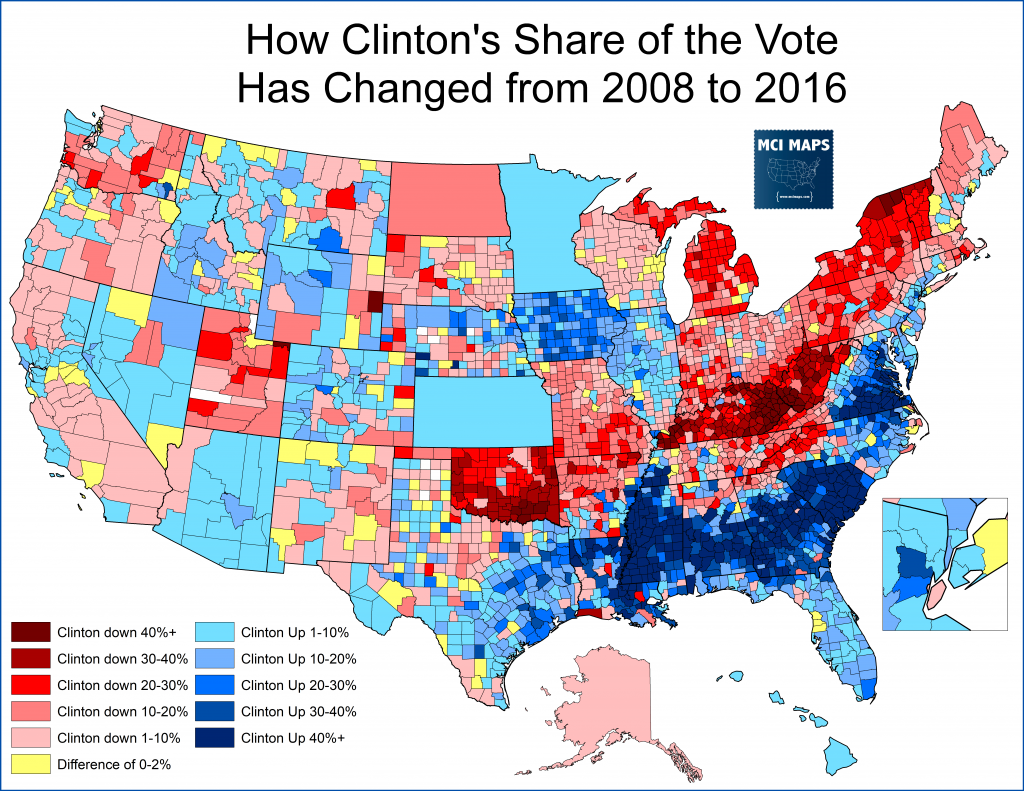

With the 2020 Democratic Presidential primaries and caucuses around the corner, I have been looking at data from past years. One map I produced was one showing Hillary Clinton’s support shift from her 2008 loss to Barack Obama to her 2016 win against Bernie Sanders. The results showed Clinton overall improving in most states; with a few key exceptions. One state that really stood out to me, however, was Utah. In the middle of the mountain west, Utah is a major Clinton drop despite being surrounded by gains.

The results are the same at the county level. Clinton fell in most Utah counties, but largely gained in counties on the Utah border.

So what happened? Well my opinion quickly turned to a key culprit. Utah was a primary in 2008, but a caucus in 2016.

Caucuses vs Primaries

You’ve no doubt heard of both primaries and caucuses when discussion has come up about the Democratic nomination process. The “New Hampshire Primary” and the “Iowa Caucuses.” Well these aren’t just words, they mean drastically different procedures.

Primaries are the normal elections you are used to. You show up when the polls are open, cast your ballot, and leave. Depending on your state, you can vote by mail or early, and the state runs the process.

Caucuses are run by parties and often involve a designated time of day for people to meet. Your caucus might be at 3pm. You show up, vote either with a ballot or by going to the side of a room, and may be there for an hour or more. Every state caucus is a bit different and some processes last longer than others. Caucuses often mean having to arrive at a specific time. What this universally means is caucuses have lower turnout – as not everyone can commit themselves to a specific time of day. Caucuses therefor favor candidates with stronger ground games and those with fan-bases that are very energetic.

During the 2008 and 2016 nomination fights, Hillary Clinton was always weak in the caucuses. Her campaign never focused heavily on them, instead fighting more for major primaries. Meanwhile, Obama and Sanders both had loyal and energetic fanbases that would show up and swing the low-turnout caucuses in their candidate’s favor. Clinton only won the Nevada caucuses in 2008 and barely won Iowa in 2016. Every other caucus voted for one of her opponents.

One interesting data point emerged when looking at the past nominations. A few states have actually held caucuses that are binding for delegates, but then also had non-binding primaries later in the year. Looking at these differences would provided an opportunity to examine the effect of the election type on candidate preference.

The 2008 Democratic Nomination

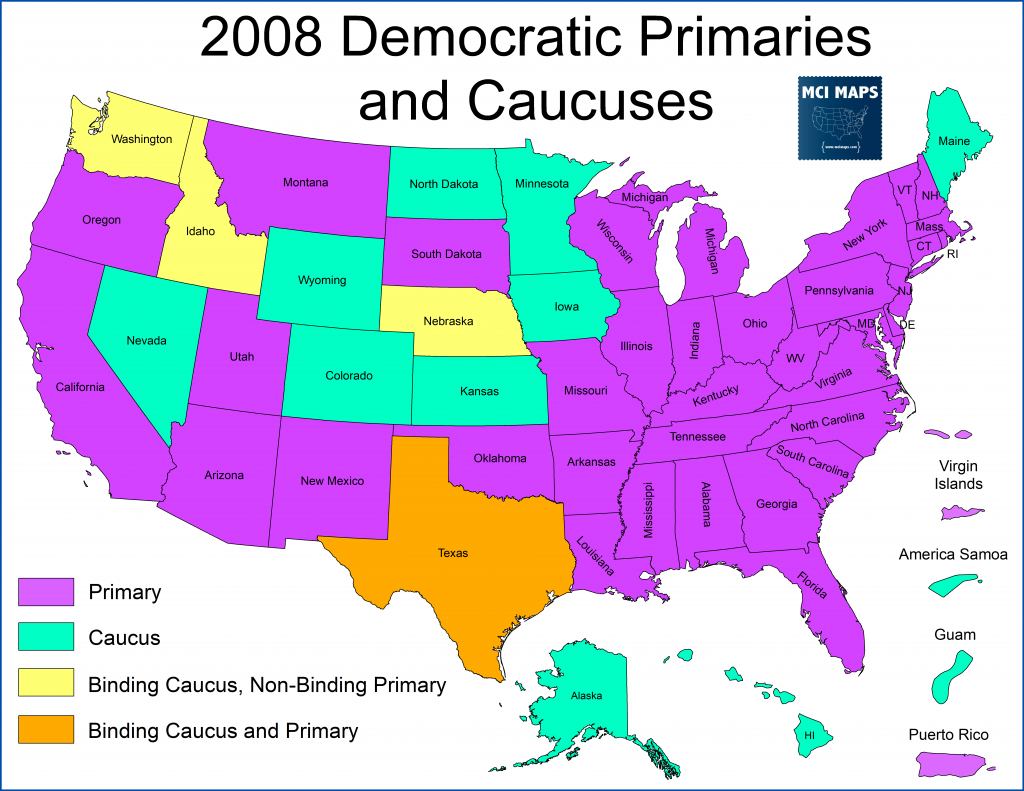

In the 2008 Democratic nomination process, 14 states held caucuses. Of these states; Idaho, Washington, and Nebraska also held non-binding primaries. Texas had a unique system called the “Texas Two-Step”; which saw a delegates picked from both a primary and caucuses system.

Caucuses were a very lucrative avenue for Obama to get delegates. The Clinton campaign did not invest much in caucus states while Obama’s campaign invested heavily in ground game operations to maximize delegate allocations. Caucuses were well-suited for Obama’s field organization and his energized fan-base.

Idaho

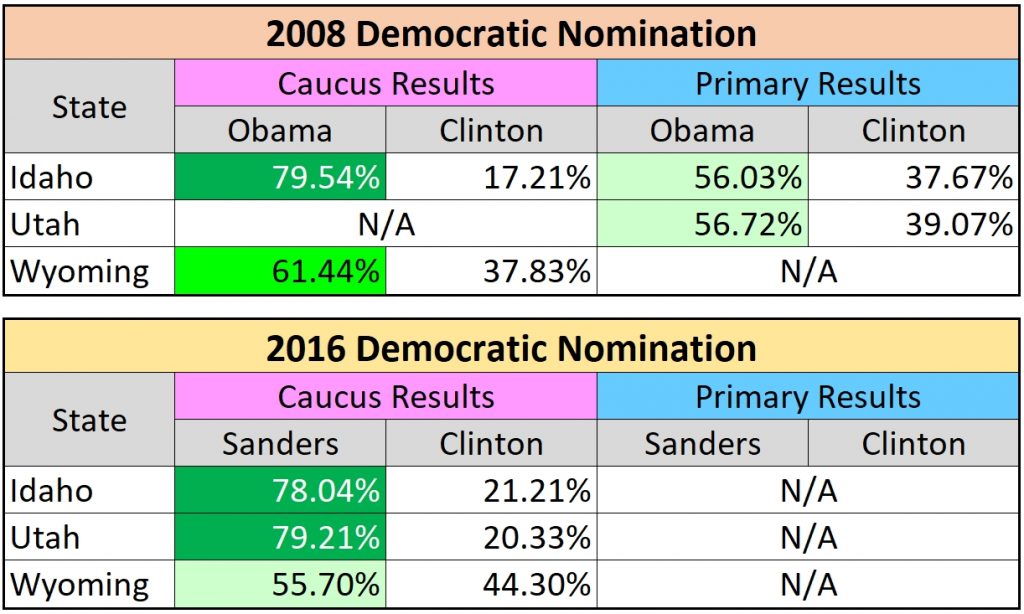

Idaho’s primary was part of super Tuesday and was largely overlooked by national press at the time. Like many caucuses, Obama racked up a large win; taking nearly 80%. A primary was held in May, close to the end of the nomination fight, which saw Obama win; but with a smaller margin.

The Idaho primary, held to coincide with regular primary elections, saw double the turnout as the caucus.

Washington

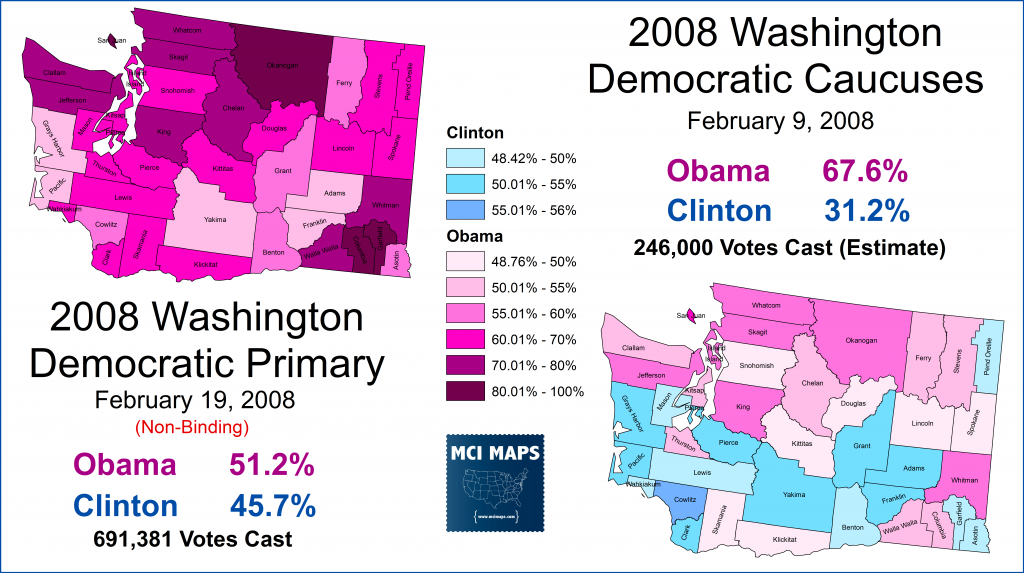

The Washington primary got the most attention during the 2008 nomination process. The Washington caucuses came just days after Super Tuesday, with the non-binding primary just ten days later. The Clinton campaign, sensing its problems in caucuses were going to lead to a delegate deficit, made an issue of the causes – pointing out its limitation on voting by requiring people to come at a specific time of day. Obama went on to win the caucus, as expected, by a 2-1 margin. The primary held 10 days later, was much closer, with Obama securing a 6 point win.

Washington caucus turnout is never official and an estimate given by the party, which said the total was around 246,000. This was a record, but it still fell far bellow the the near 700,000 who voted in the primary.

Nebraska

The Nebraska caucuses were the same day as Washington. Like the others, they saw a major Obama victory. The primary that emerged in mid-May saw a 3 point Obama plurality win.

Like the contests before, the primary saw far stronger turnout.

The Texas-two step saw Clinton win the primary, but the lose the caucus that took place 15 minutes after primary polls close.

In the end, all caucuses except for Nevada went to Obama. The campaigns superior ground game, dedicated supports, and Clinton campaign’s focus on just primaries all contributed to massive delegate hauls. These were instrumental in helping Obama secure the nomination.

The 2016 Democratic Nomination

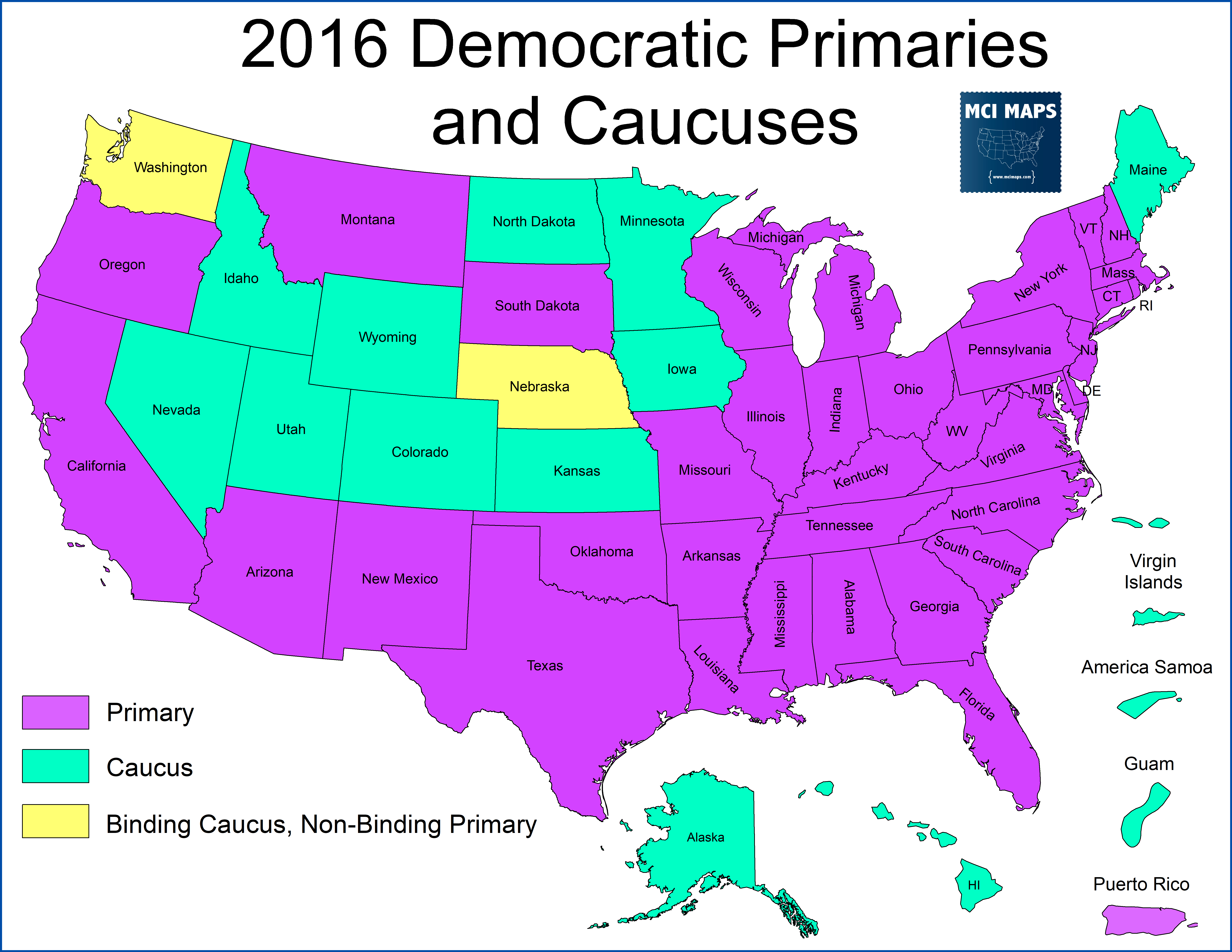

The 2016 primaries again saw 14 states hold caucuses – but with a few differences. Texas abandoned the two-step system and went entirely to a primary. Meanwhile, after funding was cut from the state, Utah was switched from a primary to a caucus.

Idaho also removed the non-binding primary from its schedule. This time non-binding primaries would only take place in Nebraska and Washington.

Nebraska

Nebraska’s caucuses were held a few days after Super Tuesday and like most caucuses, saw an easy Sanders win. The margin was as wide as it was against Obama, but still a double-digit showing. The surprise came in May, when it was reported Clinton had won the non-binding primary with 53%.

Turnout was double that of of the caucus. This marked the first time (beside the Texas two-step) that the caucus and primary yielded different winners

Washington

Later in March, Sanders, reeling from losses in FL, OH, NC, MO, and NC, won several western caucuses. One of his biggest was Washington, where he took 73% of the vote. Two months later, Clinton would win the Washington primary 52-47. An amazing swing.

Primary turnout was triple that in the caucuses. The margin difference also brought new spotlight on the caucus vs primary issue.

2016 Conclusions

Clinton’s caucus troubles from 2008 continued into 2016. In the mountain west, she did just as bad in Idaho has she had in 2008. She did improve in the Wyoming caucus, with the state being against her but by a smaller margin than Idaho. This is likely due to the fact that Wyoming has a closed caucus, where only registered democrats can vote. Closed caucuses were often better for Clinton than those that allowed non-democrats to vote.

Meanwhile, her modest loss in Utah’s 2008 primary turned into a landslide in the 2016 Utah caucuses.

I wanted to look at these three states because they are notably similar. All three are heavily white and share borders. Notice that in 2008, the Utah and Idaho primaries showed similar results. The states voted in near lock-stop – all the while the binding Idaho caucus was an Obama landslide. Move over to 2016 and the Idaho and Utah results are again in lock-step, but this time on the caucus side. These similar results shouldn’t be surprising, as the democratic makeup of the states is similar. This reinforces my hypothesis that the reason for Utah’s massive swing away from Clinton was due to the move from a primary to a caucus.

Clinton’s weakness in caucuses was mitigated this time by her strong wins in the south, where she racked up large margins in states with large African-American populations. This allowed her to secure a comfortable win despite her caucus troubles.

The 2020 Democratic Nomination

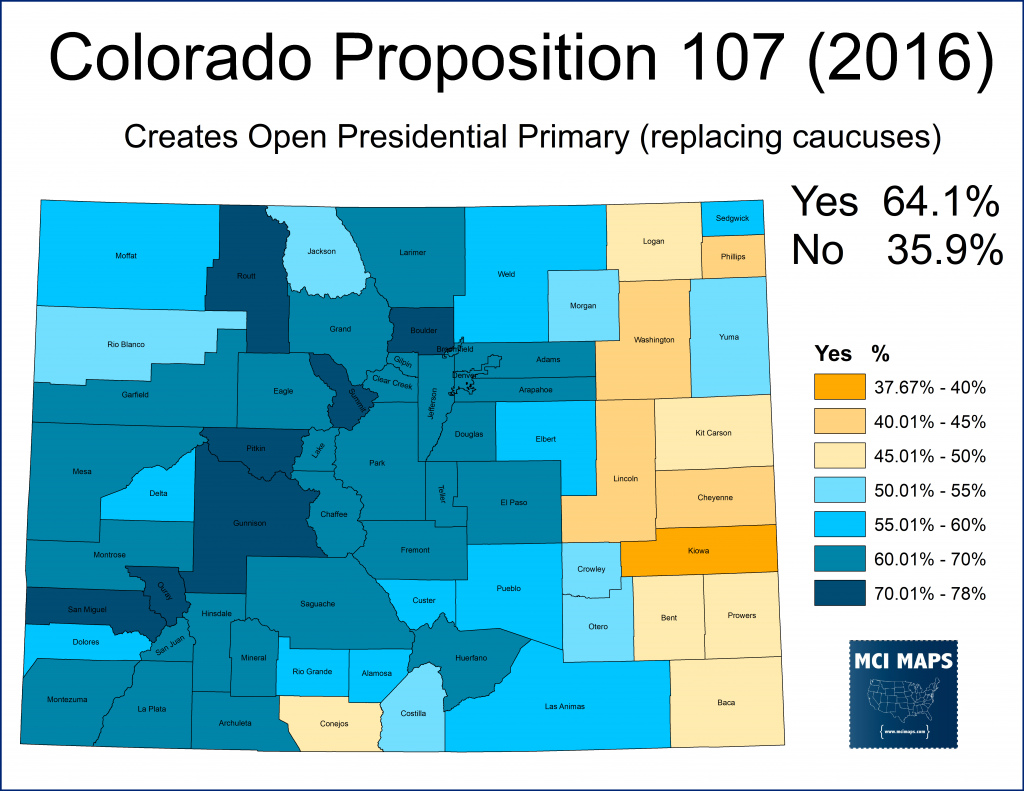

The scrutiny of the caucus system reached fever pitch after the 2016 contest. Different results and the issues with participation caused many states and local parties to move away from caucuses. State parties either made decisions, or states enacted legislation. Colorado made their change via a ballot measure.

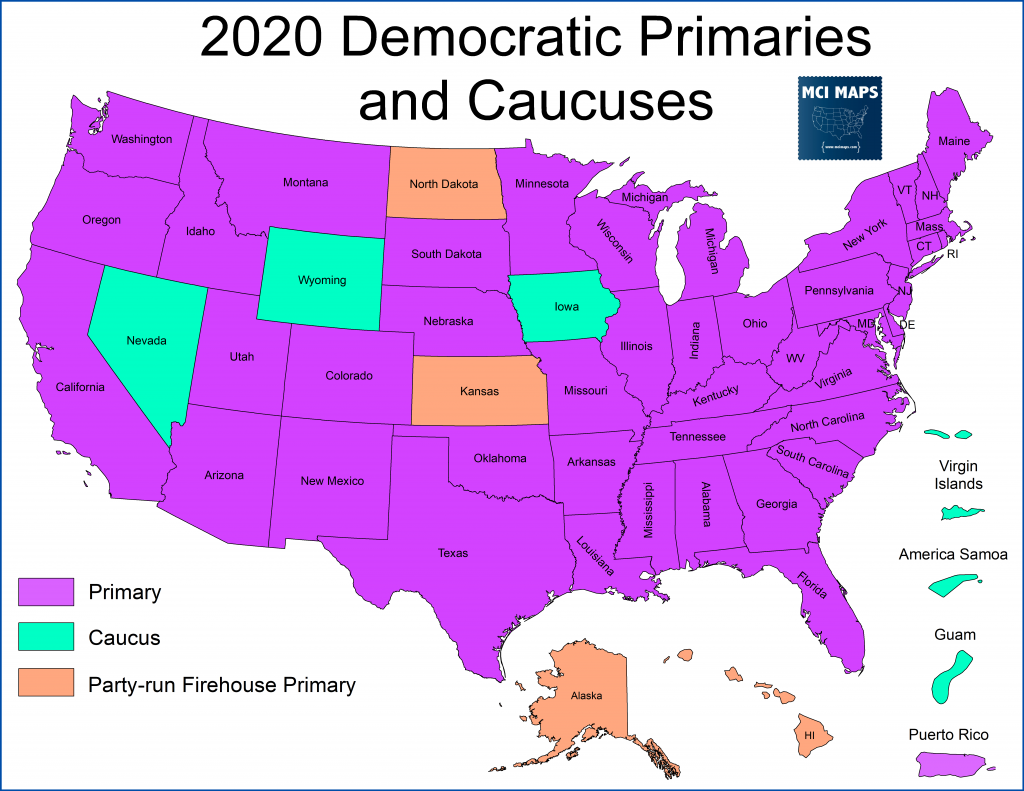

In the end, a vast majority of caucus states voted to move to primaries. As of now, only three caucuses remain in states: Iowa, Nevada, and Colorado. In addition, several territories will use caucuses. North Dakota, Kansas, Alaska, and Hawaii have moved to party-run primaries; known as firehouse primaries. These will feature polling sites run by the party and open for several hours during the day, but often not as long as a state-funded primary. These are still expected to attract better turnout.

As 2008 and 2016 show, the different electoral system can yield different results. The elimination of many caucuses is no doubt a blow to Sanders, who’s dedicated supporters could have no doubt swung many caucuses to his favor. However, the move is not a death blow to the candidate either. The additional primaries are sure to generate stronger turnout in many of these states. Who benefits from that remains to be seen.