On October 21st, Canada held its federal elections. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his Liberal Party were facing a tough campaign. Polls showed them narrowly trailing the Conservative Party and scandals regarding corruption and Trudeau’s past were hurting the party. The Liberals countered by focusing on the prospect of Conservative rule and working to consolidate left wing voters that were defecting to the Greens, NDP, and the Bloc.

Looming Shadows

Many local elections in 2018 and 2019 seemed to point to trouble for the Liberal Government. Conservatives gained control in Montreal and Quebec in 2018 – before the bigger scandals hit Trudeau. 2019’s provincial government resulted showed a steady string of good results for Conservatives and bad results for Liberals.

It should of course be noted that local results don’t always predict federal results. As many places in the United States demonstrate, local parties and local issues can differ from the national conversation. Many local Conservative Parties in Canada are more liberal than their national equivalent. Local dynamics and differing turnout also can make predictability of upcoming federal results flawed. That said, it cannot be denied the major parties were watching the 2019 provincial elections to gauge some levels of party support.

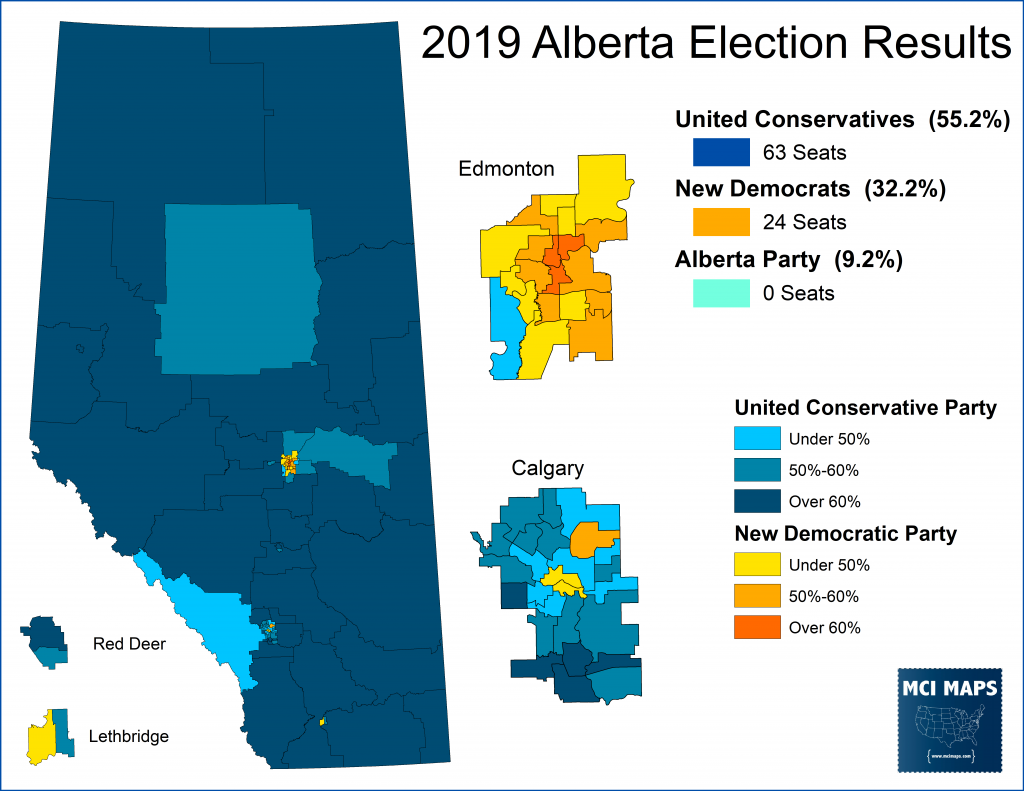

April 16th was the Alberta provincial election. The campaign saw the Conservatives, who had lost control to the left-leaning NDP in 2015 due to a split in the right-wing movement, unite and easily take back control.

2015 had seen the Progressive Conservative and Wildrose Party compete for right-of-center votes, allowing an NDP win (the Liberals don’t even seriously compete here). This time, hatred for Trudeau and the Liberal Government united the two factions into the United Conservatives – who blew past the NDP.

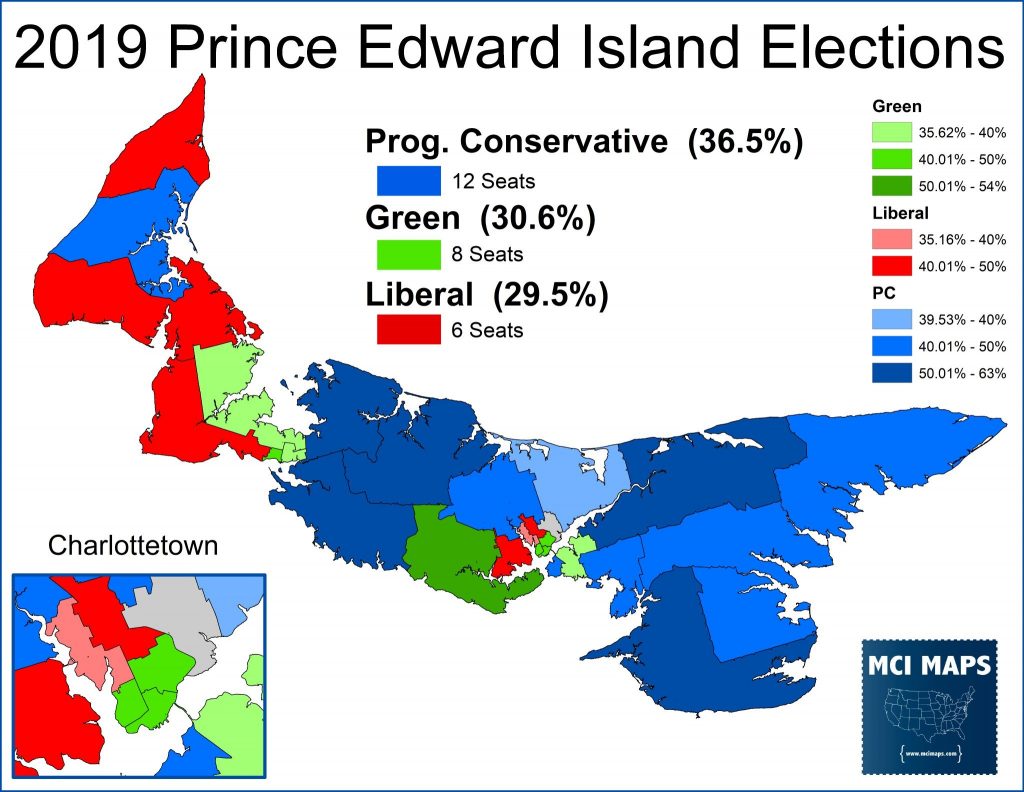

April 23rd was the Prince Edward Island provincial elections. The Liberals had a majority on the provincial council and held all the provinces federal seats. However, the local liberal government was unpopular and fell into third place, losing out to the Conservatives and the Greens.

Polls had indicated a Green government was possible, but they also underestimated the Progressive Conservative support.

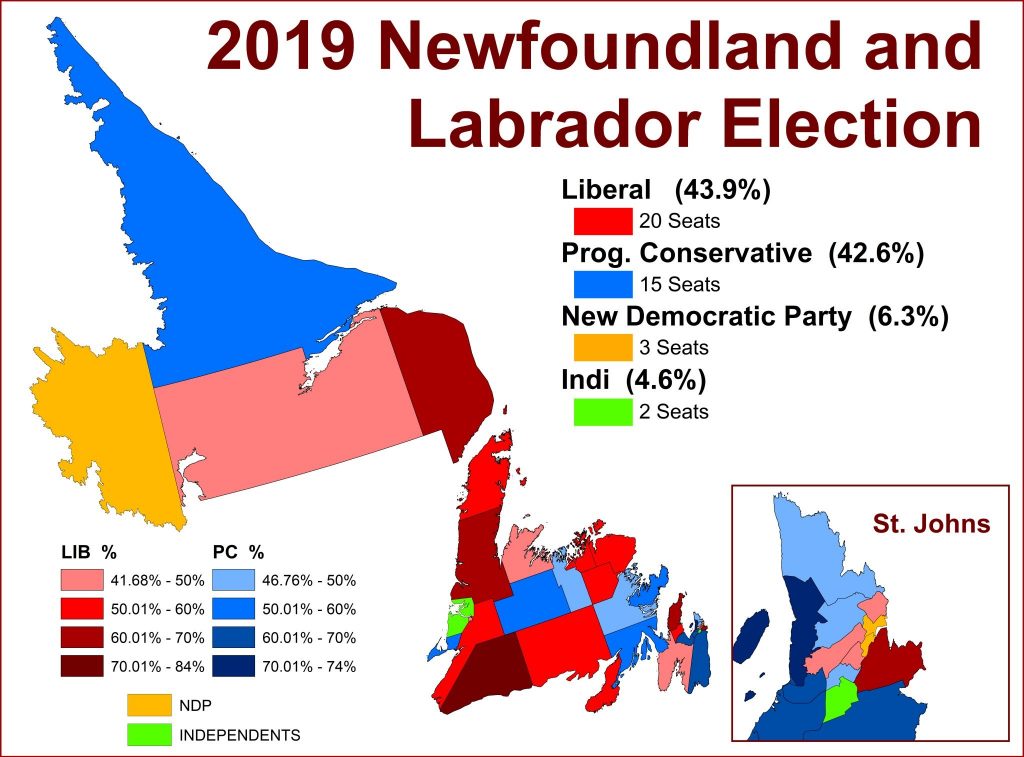

May 16th was the Newfoundland and Labrador provincial election. Like PEI, this was a solidly liberal local government and the national Liberals held all its parliament seats. The local party lost 7 seats, allowing them to held 20/40 – hence forming a minority government.

Perhaps the only halfway decent result for the left was in Manitoba, which voted on September 10th – a time when the federal elections were looming on the horizon. The incumbent Conservative Government lost 2 seats, Liberals lost 1, and the NDP gained 6.

This was a slightly better left wing result, but only provided minor comfort.

Once all provincial elections were done, the Center-right held control of most provinces in the Country (map from Wiki).

Conservatives were touting the gains over the last few years while Liberals tried to downplay their significance.

The Results

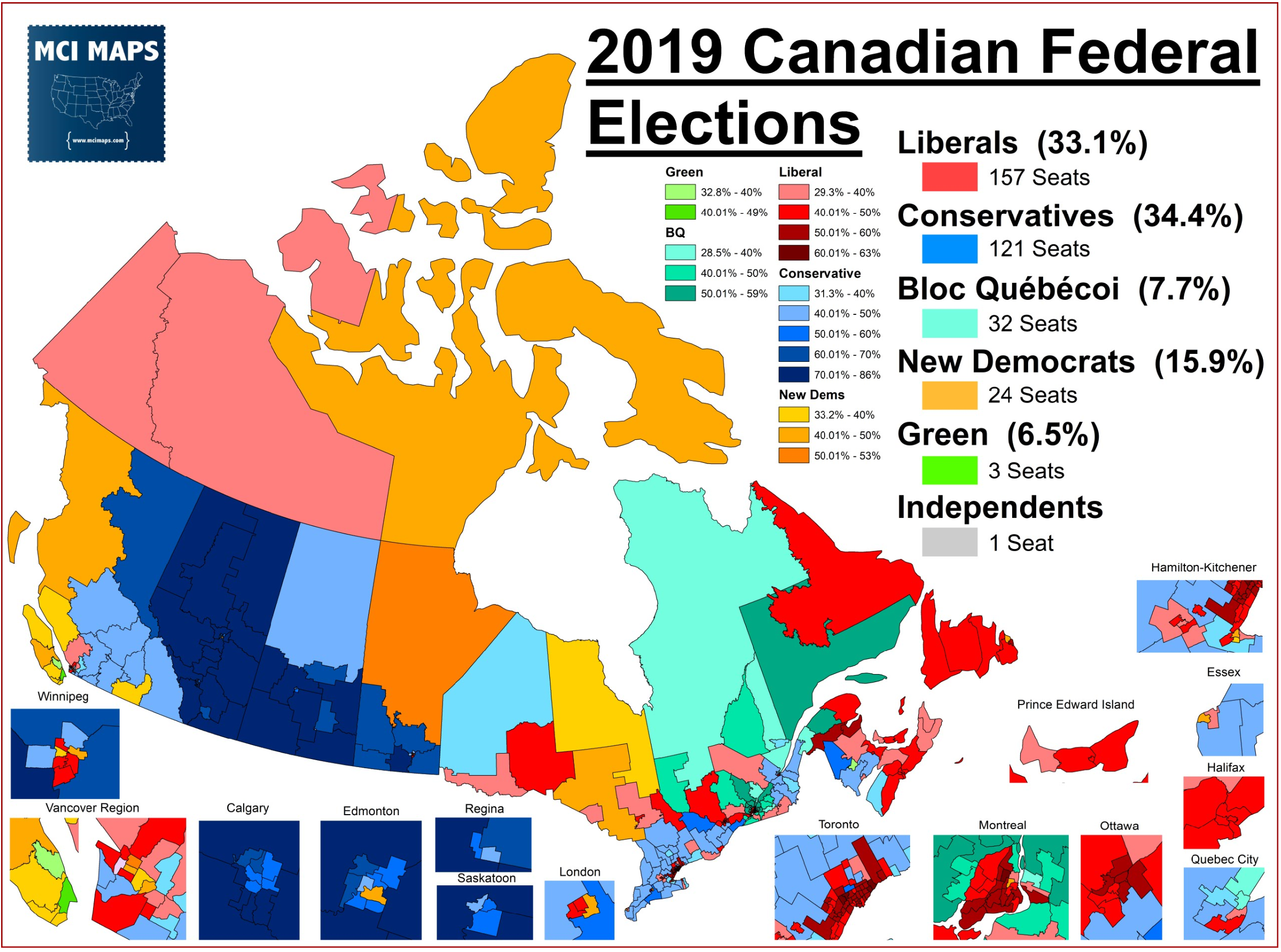

Polls were consistently close in the general election – with many believing the Liberals had a shot to hold on but knowing the Conservatives could pull away in the end. When all the votes were counted, the Liberal’s remained the largest party in the parliament. They did lose their majority; taking 157 seats (with 170 being needed for a majority) – but were well ahead of the 121 held by the Conservatives.

The Bloc Quebecoi Party, a secessionist party out of French-speaking Quebec that overall is left of center, gained 22 seats and surged to 3rd largest in the parliament. The NDP, also left of center, lost 15 seats, but still holds 22 seats in the chamber. It is expected the Liberals will work with these parties to try and advance legislation – though no formal coalition will be formed.

The results were a relief for Liberals, but still represented a major drop from 2015. In those elections, the Liberals had surged to a strong majority government and placed well ahead of the Conservatives in the popular vote.

Liberals built their win by retaining 150 of their seats and making 7 gains, two from conservatives and five from the NDP. They lost 8 of their seats to the bloc in Montreal and 21 to the Conservatives. A full breakdown of how ridings moved between the two elections can be seen in the map below.

In terms of popular vote, the liberals lost ground across most of the country. However, they did gain in parts of Montreal and Toronto and other urban ridings.

Conservatives gained support across most of the nation but their biggest gains were in the western provinces. However, they lost lots of ground in the major cities – something analysts were quick to point out on election night. Some conservative commentators worried about the party becoming too reliant on less urban voters.

The NDP’s shift fluctuated across the nation – they made notable gains around Manitoba and the Atlantic provinces, but were absolutely routed in Quebec – losing much of those votes to the bloc. They also made gains in cities, taking advantage of conservative drops there but also voters’ unease with the Liberal Party.

The Green’s also gained across most of the nation, but did so the most in the Atlantic provinces and the British Columbia region.

The Popular Vote vs Seats Won

One story that quickly emerged after the votes were counted was that the Conservatives finished 1% higher in the popular vote, yet came up short on seats. This was discussed as a possibility before the election as well. The Conservatives got huge margins in the right-wing western provinces like Alberta, but their showing in big provinces like Ontario and Quebec were much weaker than the party had hoped.

Liberals also lost popular vote ground to the Conservatives and Greens in the Atlantic provinces, but this resulted in only a few seat changes.

It is also worth noting the Conservatives were on the cusp of taking many additional Liberal-held seats. 17 ridings/seats saw the Liberals outpace Conservatives by just 5%, which another 16 being between 5-10%.

The province-level vote is really critical for understanding how the popular vote vs seat allocation phenominon could occure. The table below shows the vote by province for both 2015 and 2016. As the data shows, the conservatives gained and liberals lost in western provinces and Atlantic provinces.

The 2015 and 2019 result maps are below.

The results were solidly blue provinces like Alberta and Saskatchewan getting bluer, and the red Atlantic getting less red. The problem for the Conservatives was all these provinces are smaller in population and therefore, have fewer seats. In addition, the blue western provinces already had solid Conservative seat leads – leaving only so many gains to be had.

The shift in popular vote and seat swings can be seen in the table below.

The small shifts in Ontario and Quebec were critical for Liberals holding onto their seat lead. Conservative jumps in the Atlantic and West combined to allow them to lead the popular vote – but the seat change was minimal.

In essence, the conservatives gained votes in areas where they already controlled most of the seats and Liberals lost ground in areas where they controlled few seats to begin with, or had such large margins they only lost a few as a result of popular vote drops. Most importantly, Ontario and Quebec, the largest provinces, saw only modest popular vote shifts between the two largest parties.

I took a detailed look at all these provinces.

The Western Prairie Provinces

Alberta is the capital of opposition to Trudeau and the Liberal Party. This manifested itself with the Liberals losing 11 points in their popular vote there and the Conservative’s gaining 10 points. However, this only resulted in flipping four seats; shutting the liberal party out of Alberta.

Saskatchewan, right next to Alberta, was the same. Conservatives gained 16 points while the Liberals lost 12. However, conservatives already dominated the seats in the province. The result was the last held liberal seat falling to the Conservatives. The right-wingers also gained 3 NDP held seats. But for such major popular vote switches, these are still just a handful of seats.

Manitoba saw the Liberals lose 18%, but due to their low seat-holdings anyway, they only lost 3 seats (2 to liberals and 1 to the NDP). The Liberals did hold on to three seats in Winnipeg – highlighting conservative problems in cities we already discussed.

Quebec and Ontario – The Seat Kingdoms

The largest province, Ontario, is where conservatives really needed to make gains. However, the relatively small popular vote shifts led to only a handful of seats changing hands. Conservatives gained four liberal seats, but then lost two back. An extra pickup from the NDP left them with a net gain of just 3. This was a lower gain in Alberta – despite Ontario having 4x the number of seats.

Quebec was a similar story for Conservatives. This was a province they needed to make gains in, but instead they left with fewer seats they came in with. They only took 1 liberal seat and lost 3 to the Bloc. The re-emergence of the Bloc is the big story of the election – as they had fallen into low party status after 2015. The Bloc’s rise really came at the expense of the NDP as well as the Liberals.

For those unfamiliar with the Bloc, here is the quickest summary in history. Quebec Province is unique in Canada for being majority French speaking and much more ingrained in French-inspired culture. This stems from colonization and French presence in the area hundreds of years ago. Canada is overall much more English influenced, with Quebec standing out as the lone French province. The native language map of Canada is below.

Native French speakers are actually outpaced by “other” language groups – notably Inuit and other First Nation languages (which dominate in Nunavut). The Bloc is a party that advocates Quebec becoming its own country, something that game within 1% of passing in a 1995 referendum. The Bloc continues to advocate sovereignty, but secession pushes have never reached the same fever pitch they did in 1995. Canada has worked to integrate French culture into its overall society, and the Country maintains two official languages – English and French – despite few outside Quebec even speaking French. The Bloc is overall a left-wing party, though some cultural issues make them more conservative. The Bloc fell drastically in recent years, but this election saw them re-rise to majority-party status – with many of its winners being younger candidates.

Francophone voters clearly backed the Bloc, which in addition to its Quebec secession roots, still is a fierce advocate for Quebec and French culture interests. Only Montreal, which is more diverse and less French, withstood the Bloc’s rise.

Pacific Coast

British Columbia is perhaps the one province were vote shifts really maximized in the Conservative’s favor. A 9 point drop for the Liberals resulted in them losing 5 seats to the Conservatives – who also took 2 NDP seats.

Independent Jody Wilson-Raybould, who had been the Liberal Attorney General before resigning, won her seat in Vancover. Her resignation was what set off a one of the scandals for Trudeau over him trying to influence an investigation.

The Atlantic Provinces

The Atlantic provinces saw major liberal drops but few liberal seat losses. These stand out as perfect examples of the anti-Liberal vote being too split and not concentrated. In all these provinces, the Liberals were still the largest party in terms of votes, but their drops were dramatic from 2015

In Nova Scotia, the Liberals dropped 21%, but the Conservatives and Greens each only gained 8% each. The split in the opposition allowed the Liberals to only lose one seat while retaining 11 of the 12.

In New Brunswick the liberals dropped 14%, but the Conservatives only gained 8%. Green’s were the biggest gainers here and as a result picked up a seat. the Conservatives, meanwhile, gained 4 seats. The Liberals did retain 6 of their seats.

Newfoundland saw the Liberals drop 20 points and the Conservatives gain 18. However, the 2015 margin was so wide this still resulted in Liberals being well ahead of Conservative in the vote (45% to 28%). The conservative rise from Liberals actually just weakened them enough to lose a seat in St Johns to the NDP.

Finally, in Prince Edward Island, a 15 point Liberal drop resulted in no seat changes. The NDP’s 8 point fall combined with the Green’s 15 point rise resulted in an opposition so split that the Liberals still led in the province by more than 10 points. As such, no seats changed.

The Atlantic results were truly stunning for how few seats changed despite the Liberal popular vote drops. Split opposition saved the Liberals in the Atlantic.

Looking Ahead

Trudeau’s government will forge ahead and hope to avoid needing to call a snap election in a year or two (minority government’s rarely last their full term). In the meantime, electoral reform may re-emerge as a major issue. Canada’s First-Past-The-Post system is struggling to deal with so many different parties with different regional strengths. However, its not clear reform has popular support (though maybe these results will change it). More representative results always polls well, but when voters are given options, they sometimes balk. This was seen earlier this year in Prince Edward Island, where a referendum to go to proportional representation narrowly failed.

This referendum failed the same time voters were electing three different parties to their local government.

Whether or not electoral reform advances in Canada remains to be seen. In the meantime, Liberals hold on to power thanks to bruising campaign and a little electoral luck.