As Americans continue to speak out, march, and protest against racism in society; a movement sparked by the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, we are seeing a new round of statues and monuments dedicated to the Confederacy and Jim Crow coming down in America. Across the south, statues of confederate heroes are being taken down as local and state governments acknowledge the pain they represent. Many state and localities have been warm to removal while others have resisted. The next fight over symbols may be brewing in Mississippi; where the states flag is the source of scrutiny.

Over the last few days, the NCAA and the SEC have warned the state of Mississippi that their state flag could put them at risk to lose out on hosting championship events. This is the most direct economic threat that the state has faced. Mississippi remains the last state in the nation to have such prominent symbolism of the Confederacy and Jim Crow on their flag.

Race in Mississippi

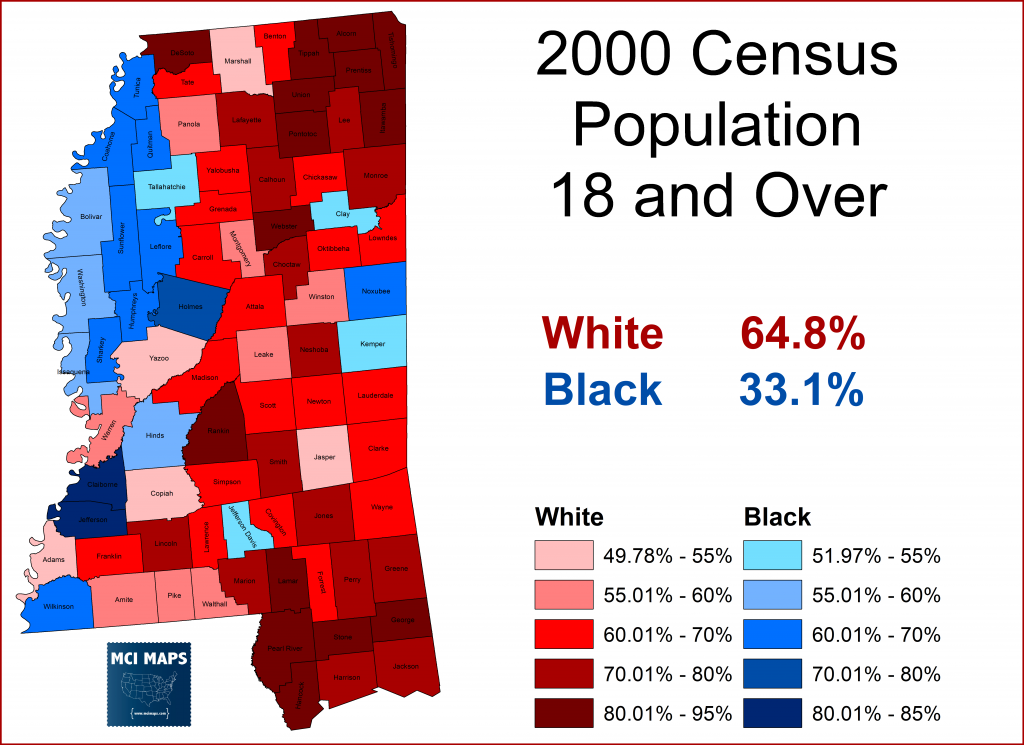

Mississippi’s African-American population hovers right around 37%. However, for the purposes of this article, we are going to focus on the population over 18. As a share of voters over 18, the state breaks down to 65% white and 33% African-American.

Mississippi’s racial history in America is infamous. In 1964 it was decreed the most segregated state in the nation, and in the election that year it gave Barry Goldwater over 87% of the vote – a violent rejection of LBJ’s Civil Rights program. To this day Mississippi still has some of the most racially polarized voting in the country.

So, in 2001, when Mississippi held a referendum on its state flag, everyone knew race was going to be a major factor.

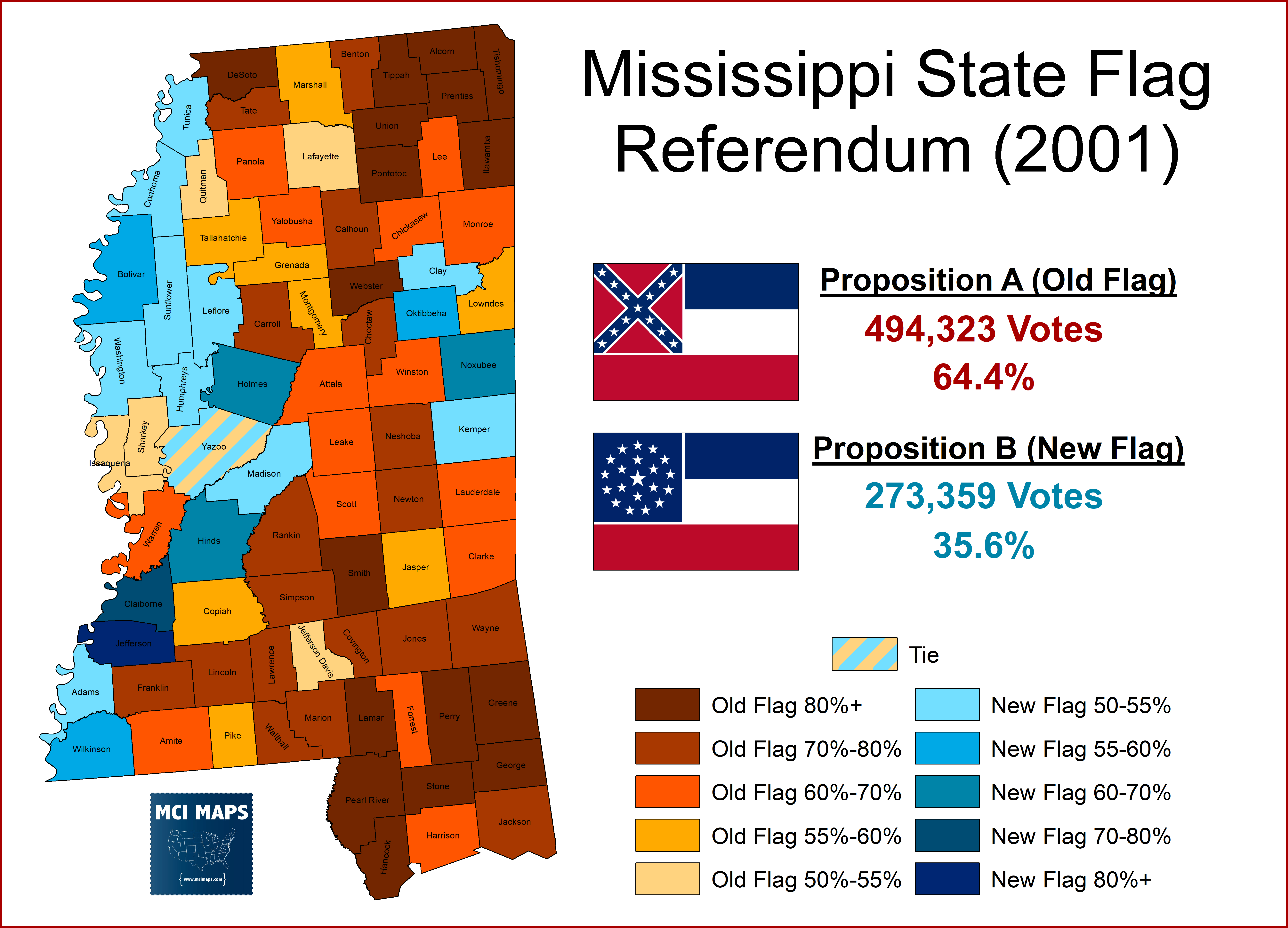

The 2001 Referendum

Mississippi’s flag had been a sore subject for a good deal of time. However, the referendum came about thanks to a legal technicality. An NAACP lawsuit argued the flag was invalid because when Mississippi updated their legal code in 1906, it forgot to include provisions for the state flag. The Supreme Court of Mississippi agreed and ruled in 2000 that the state had no official flag. This was a technicality that could have been fixed by a new legislative vote to affirm the flag. However, Democratic Governor Ronnie Musgrove, who favored a change, opted to form a committee to study the issue and consider a new flag as a possibility.

Eventually a new flag design was considered and it was decided a referendum would be help in April of 2001 to decide on the old flag or the new. The referendum was going to be a tough hill to climb, but proponents of a new flag preferred it to the legislature; where it was believed the old flag would prevail. Governor Musgrove, former Governor Winter, the NAACP, and the Mississippi Economic Council (think Chamber of Commerce) all favored the change. New flag proponents spent $600,000 on the measure, compared with the $125,000 from backers of the old flag.

Throughout the campaign, a victory for the new flag was an uphill climb. Proponents hoped the campaign would generate support, but it did not materialize. There were two major issues. First, old flag backers weren’t convinced the state would be economically harmed by retaining the old flag (indeed no business threatened the state). Second, many younger voters and African-Americans were pessimistic they could win, and hence getting them galvanized to vote at all became a real issue.

The enthusiasm was going in the wrong direction. Many old flag supporters were riled up and angry about the proposed change and railed against “outsiders” dictating to them. Meanwhile, the NAACP noted pessimism among the African-American population and their likely weaker voter turnout.

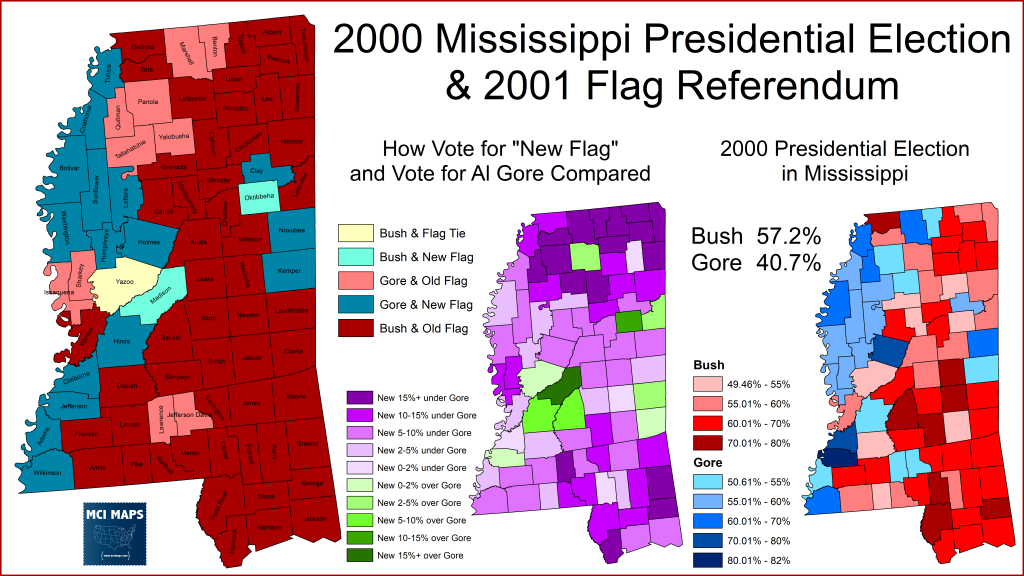

The results came in as an expected loss for the new flag. By a near 2-1 margin, the old flag had won. County-level results closely mirrored the racial makeup of the state – with the delta voting for the new flag and most of the rest of the state voting for the old.

The old flag won several counties that Al Gore had won in the 2000 Presidential contest. Meanwhile, Oktibbeha (MSU) and Madison (Jackson suburbs) voted Bush and then for a new flag.

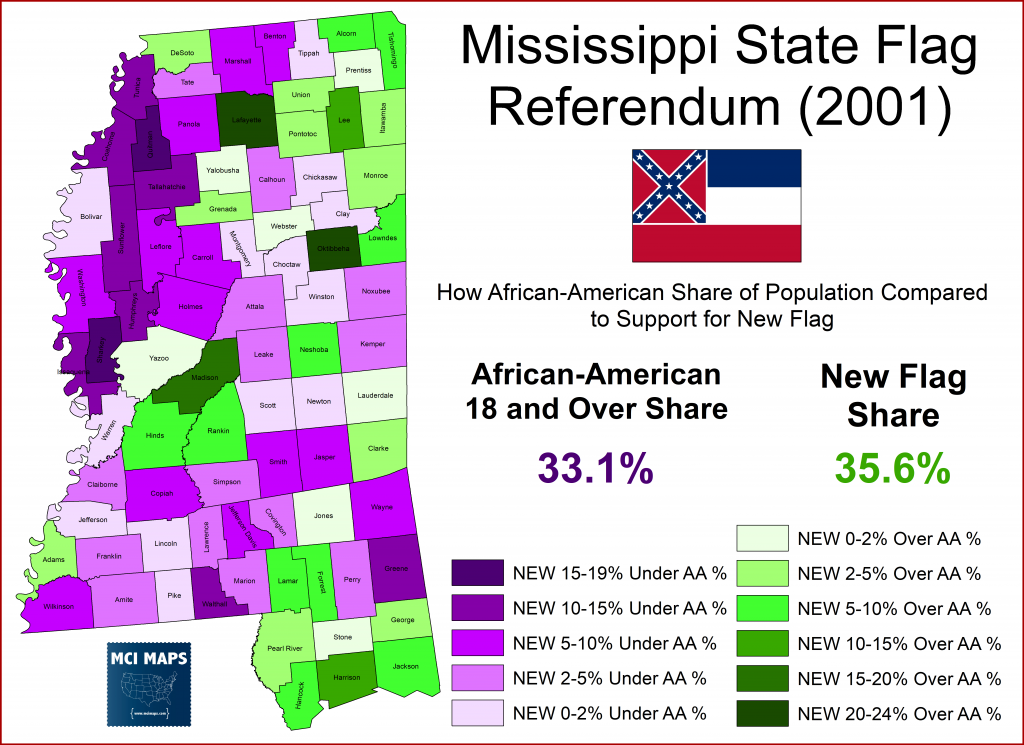

Racial census data and the referendum’s votes don’t perfectly line up. In fact, the new flag under-performed the African-American share of the population across the delta. Meanwhile, it over-performed in parts of the Northeast foothills and along the gulf coast.

The biggest over-performing counties were

- Madison – an suburb of Jackson, MS

- Lafayette – home to the University of Mississippi

- Oktibbeha – home to Mississippi State University

Despite under and over performances, the vote on the flag referendum heavily correlates with race. The African-American share of a county correlated with the vote for a new flag with a score of 0.84. This was higher than the correlation between Gore and race, which came in at 0.8.

The county data conforms with precinct analysis that researchers at the time performed. Jere Nash and Andy Andy Taggart, who wrote “Mississippi Politics: The Struggle for Power, 1976-2006,”, used precinct data to argue 95% of African-American voters supported the new design while 90% of white voters backed the old design. The found that of the 1,300 majority-white precincts in the state, only 43 backed the new flag – most in the Jackson suburbs and college towns.

Turnout Issues

Turnout was a major issue in the delta and helps explain the drop in support for the new flag. Proponents of the change noted during the campaign that there was an apathy from many African-American voters on the referendum; with many not believing it could be won. Turnout did appear to be an issue in the delta. Whether looking at votes cast as a share of the 18+ population, or turnout as a share of the votes cast for President, turnout was weakest in the west.

This apathy among African-American and younger voters ran counter to some fierce loyalty to the old flag from white residents. This quote from a white resident in the delta really stood out as an example of the toxic nature of race relations in the region.

The white resentment over the flag debate (something I personally find completely asinine) likely fueled higher white turnout in the delta, and thus the electorate that showed up was more white than the census figures. There is plenty of historic data showing white residents in heavily African-American portions of the south having more hardened and negative racial attitudes than those in more homogeneous white areas. An electorate where white voters in the delta surged out to “defend their flag” and African-American voters remained apathetic is a very plausible scenario.

Looking Ahead

The general consensus is many in the business committee and many politicians want Mississippi’s flag to change; as it serves as an embarrassment to the state and makes it look stuck in the past. However, the racial divide over the issue makes it a third rail in much of the state. However, there are signs that public opinion has been moving on the issue. A 2017 poll found just 49% support the current flag and found that whites under 55 favor a change. 2019 even saw many businesses and organizations stop showing the flag whenever possible.

The threats of the NAACP and the SEC will likely cause Mississippi to revisit the flag issue. Of course the threat from “outsiders” could also spark a backlash. We will have to wait and see what this latest development brings.

Legislative Update

When I wrote the above article, I assumed discussions about Mississippi’s flag would occur over many weeks and months. I was shocked to see how quickly things began to move over the last week. With the legislature close to the end of its legislative session, statewide elected officials began to come out for changing the flag one-by-one. The general message was the same: the flag was divisive and caused pain. Rumblings that most elected officials wanted the flag changed proved accurate, as the Speaker of the House and many top Republicans began to work with the united Democratic caucus toward pushing through a change before the legislative session ended. Any move would require a 2/3 vote to suspend the roles and avoid the normal legislative process. By Wednesday and Thursday the plans were in motion. Legislative leaders were whipping votes and it was expected to be a close call if they had the 2/3 needed. The details finally emerged on Saturday, when HCR79 was introduced. It did the following

- Repealed the current flag

- Set up a committee to design a new flag

- Flag would be voted on for approval in November

- If the new flag was rejected, then a new design would be put before voters

- The old flag would NOT be an option

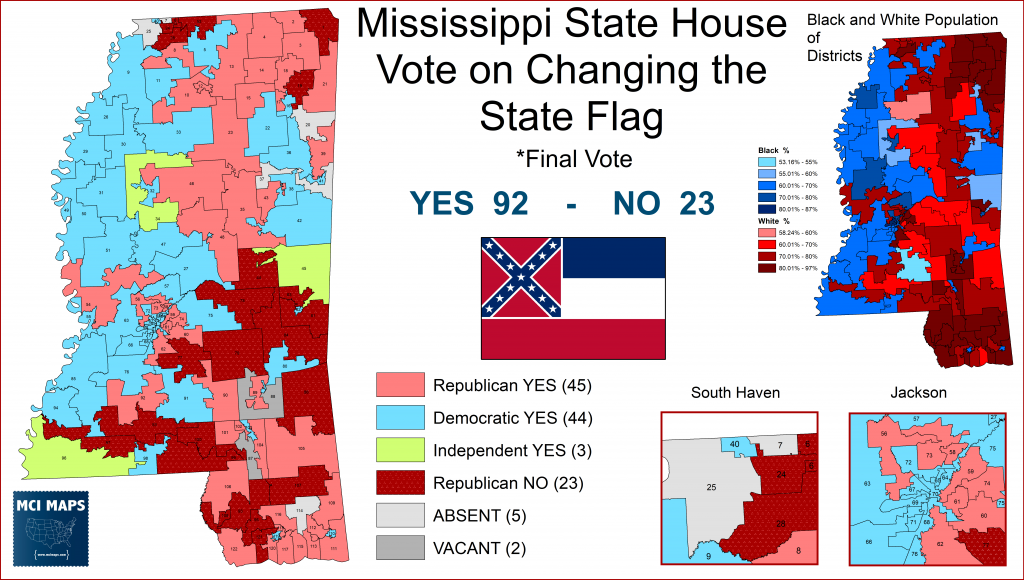

The house was first to take up the resolution. The measure cleared the 2/3 needed, scoring 84 yes votes. It received unanimous Democratic backing (including three former Dems who were not Independents) and a narrow majority of the GOP caucus.

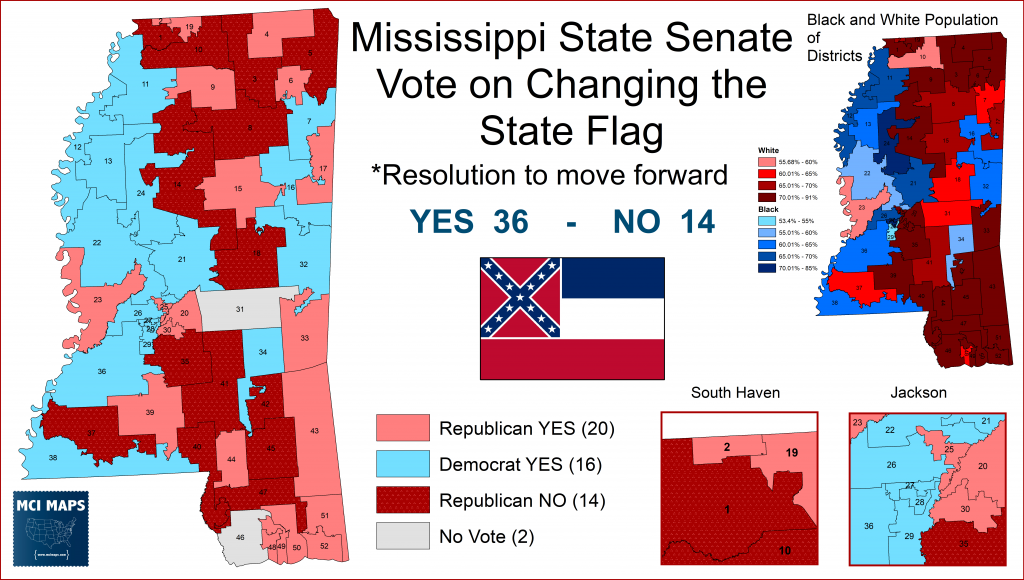

The measure went on to the state senate, where it narrowly passed the 2/3rd threshhold.

With those procedural votes out of the way, passage was a sure thing. The resolution then would need final approval, but with only majority support. On Sunday those votes came, and the House actually saw several more Republican get on board with changing the flag – boosting the measure to 92 votes.

The State Senate vote shortly fired. Two additional Republicans flipped their votes, while one flipped to NO.

Governor Tate Reeves, originally iffy on changing the flag without a public vote, has since indicated he will sign the measure.

The old flag is on its way out.