Last week, the Republic of North Macedonia had its parliamentary elections. For a vast majority of folks not fully vetted in southern European events, figuring out where North Macedonia is on a map is not always an easy task. After all, the country has only existed since the breakup of Yugoslavia, and in that conflict places like Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia got far more (negative) attention. The Republic, originally just called “Macedonia,” sits north of Greece and south of Serbia/Kosovo.

This region, referred to as the Balkans, has been the site of many kingdoms, empires, wars, and ethnic conflicts. The Youtube Channel “Geography Now” gives the Balkans the perfect name: “Europe’s most dysfunctional family.” The region is rich in historic and ethnic tensions; despite many groups having close historic and genealogical ties. In just the last 100 years, the region has been involved in the

- 1st Balkan War (good video summary)

- 2nd Balkan War (good video summary)

- WWI

- The Greco-Turkish war and its ethnic cleansing (good video)

- Yugoslavia ethnic fighting (good video on post WWI)

- WWII

- Post-war border battles, military coups through cold war

- Yugoslav Civil War and its ethnic cleansing (good summary)

As a result of all of this plus another couple centuries of history, the ethnic identity of peoples can matter a great deal in this region. With that comes names and history and modern people’s connecting to their ancestors – especially when it comes to that history giving them rights to occupy the land they now sit on. As a result, Macedonia and Greece found themselves in embroiled in a 20 year despite over nothing more than a name.

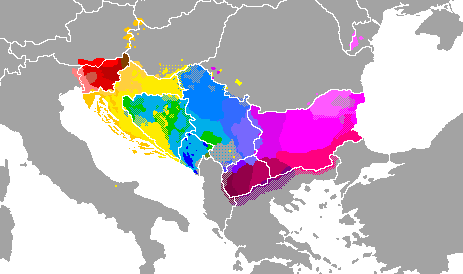

The Slavic People and Yugoslavia

Since WWII, much of the Balkans was made up of Yugoslavia; which was divided into 6 regional states, all of which with unique ethnic profiles; many of whom are broadly considered part of the Slavic ethnicity. Southern Slaves cover all parts of former Yugoslavia as well as Bulgaria to the east.

The six districts of Yugoslavia were

- Slovenia – largely made Slovenian ethnic peoples

- Croatia – largely made up of Croats but had a health Serbian minority

- Serbia – largely Serbian but Kosovo was largely Albanian Muslim

- Bosnia – mixed with makeups of Serbs, Croats, and Bosniacs

- Montenegro – Montenegrin/Serbian with Albanian/Bosniac minority

- Macedonia – Largely Macedonian, with sizable Albanian minority

Religion-wise; Croats and Slovenians are Catholic, Serbians, Montenegrins, and Macedonians are Orthodox Christians, and Albanians and Bosniacs are Muslim.

The collective began to fracture in the 1990s, the state of Macedonia was able to easily break away with little issue. Serbia and Croatia were in the middle of a budding ethnic war and since Macedonia didn’t have many Serb or Croat ethnic people’s, no one bothered to care when it opted to leave.

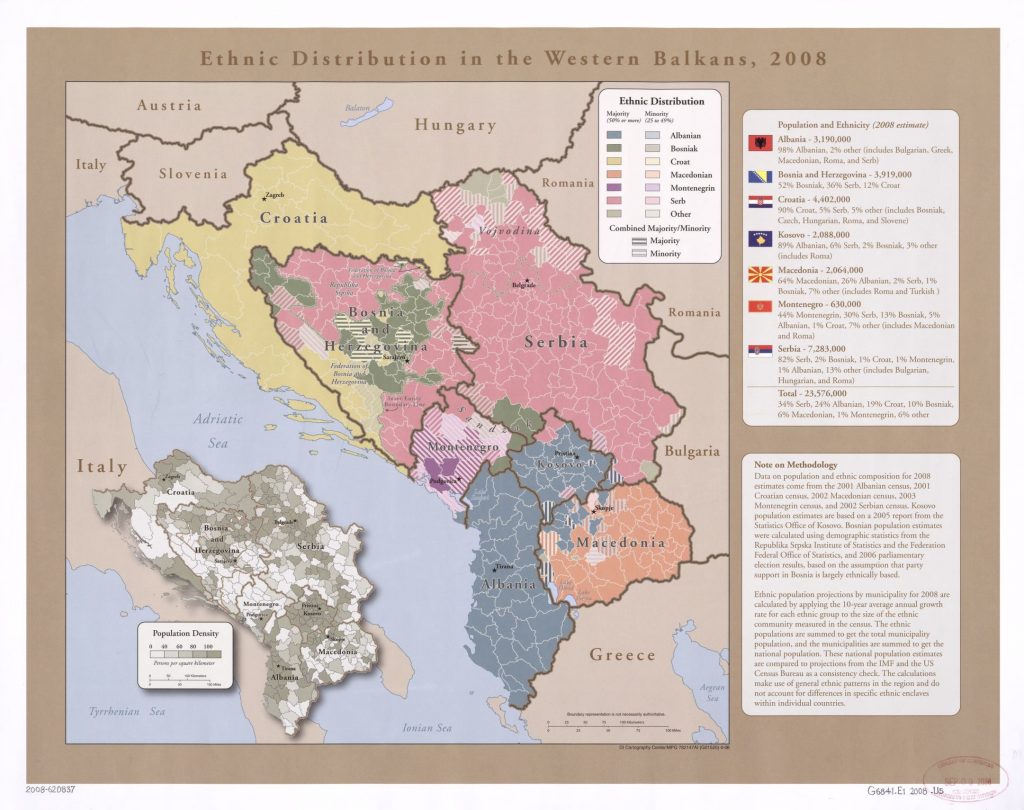

Macedonia escaped the major violence and ethnic conflict of the war, which saw ethnic cleanings, NATO intervention, and eventually millions of ethnic refugees fleeing to be on different sides of the border once the new nations were established. Below is an ethnic map of the region from 2008.

Macedonia itself is largely Slavic – with 64% of its population considering itself Macedonian (as an ethnic group). Ethnic Macedonians are largely Orthodox Christian. The next largest group is Albanian’s, who are 25% of the population are largely Muslim. The nation has seem some ethnic conflict since independence but by and large things are now relatively peaceful. Albanians are part of the political process and often play kingmaker in elections that are dominated by the left-wing and right-wing Macedonian parties.

With the area’s successful break-off from Yugoslavia in 1991, there was a new nation on the board; the “Republic of Macedonia.” This instantly became a problem for Greece.

Greece vs “Macedonia”

Greece was very much opposed to Macedonia’s name. Greece already had a region in northern provinces that it called Macedonia, and the Greeks by and large consider themselves descendant from Alexander the Great and the ancient Macedonian kingdoms. There is a great deal of history in this region; with the Macedonia name coming up multiple times.

This region all has lingeage to the Macedonian name and the borders of different kingdoms and regions (as defined by the Romans, Ottomans, or other Kingdoms). Macedonia overall as a “region” includes not only Northern Greece, but the country of Macedonia.

For the Greeks, the cocern over the name of Macedonia (the country) was that it would aid them in laying claim to the northern territory of Greece. After all, in an era where ethnicity and history could be seen as a justification for war, the concern isn’t entirely without understanding. There has been broad talk of a “United Macedonia” that would include the county of Macedonia and the Northern Greek regions, but this is not a serious plan by any government.

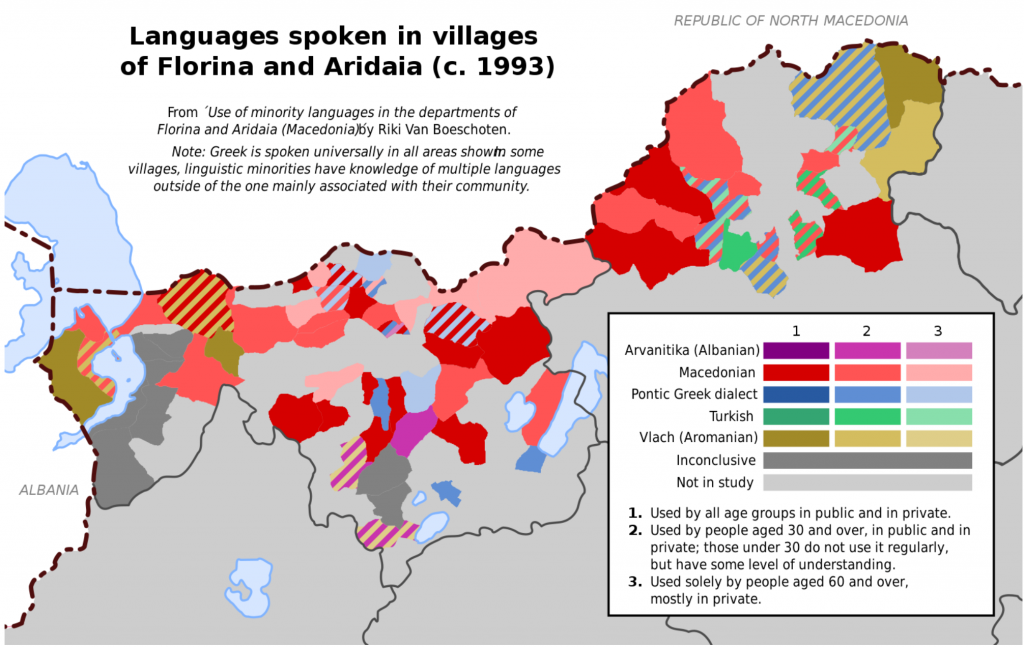

Greece does not break its census down by ethnicity, so we have less data to work with. However, the Macedonia region of Greece, which shares the border, is largely made up of people who consider themselves Greek (whether in an ethnic or national sense). However, the Macedonian language is prevalent in many of the regions villages.

In general, Macedonia the Region can likely be divided as follows

- The Republic of (now North) Macedonia; who’s ethnic majority is a “Macedonian” Slavic ethnic group

- The Northern Greek provinces, who’s residents largely view themselves as Greek, but there is language diversity

Because of Greece’s issues with the name of their country to the north, Macedonia was unable to get into NATO or the European Union; as Greece blocked their way. The name issue continued for three decades until 2018 finally saw an agreement reached.

The Prespa Agreement

In June 2018, a deal was reached between the Governments of Greece and Macedonia. Both nations were controlled at the time by left-wing governments who’s right-wing opposed the deal.

Known as the Prespa Agreement, the plan called for Macedonia to change its name to “The Republic of North Macedonia” and laid out specific clarifications noting a distinction between Macedonia the county and the ancient Macedonian people. The deal acknowledged “Macedonian” to a language that is part of the southern Slavik dialect – again denoting a difference from the historic Macedonian peoples.

The deal was widely celebrated by most in the international community and would set the stage for Macedonia to enter NATO and the European Union. The proposal, however, was widely unpopular Greece and lukewarm in Macedonia. Polls found over 65% of Greek voters disapproved of the agreement and the main opposition parties expressed anger at the proposal. Arguments against it centered on allowing their northern neighbor to retain any claim to the Macedonian name and recognition of the Macedonian language and people as something other than Hellenistic ancient Greeks.

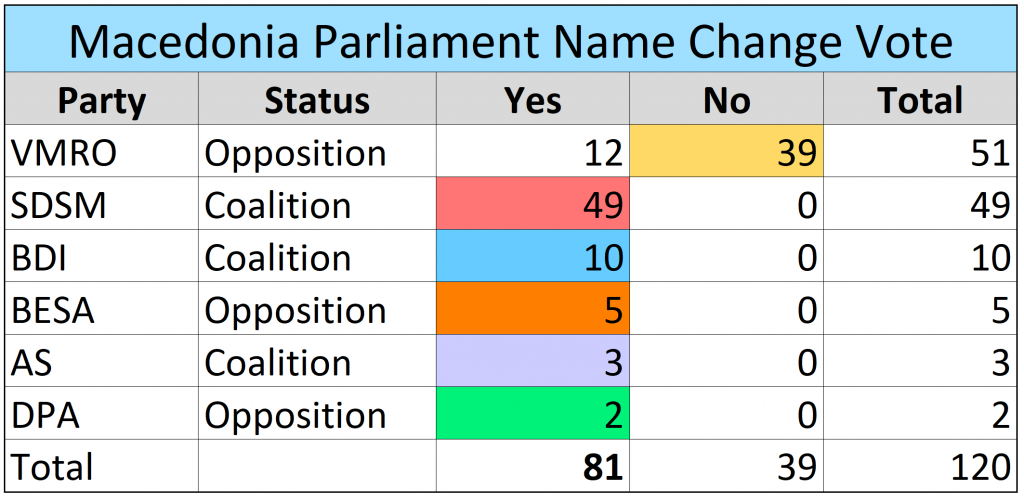

Polls in Macedonia showed a fairly even split, but the President (not as powerful as the Prime Minster) pledged not to support the agreement. Both countries saw their opposition parties oppose the deal. Later in June, Macedonia’s parliament approved the agreement with 69/120 votes. The main opposition, VMRO-DPMNE, claimed the agreement was a “genocide of the entire nation.” It should be stated at this point that the debate that would follow would be filled with widely fiery rhetoric that borders on the insane.

Macedonian President Gjorge Ivanov threatened to arrest members of parliament who supported the deal; accusing them of treason. This never happened. Macedonia set up a non-binding referendum on the proposal to be held in September of 2018. The referendum was boycotted by opposition; a strategic move since 50% turnout to be declared successful. Final turnout was 37%, with 91% voting in favor. The results could not be seen legit because of the poor turnout.

The referendum setback did not stop the government from moving forward. After months of working out the finer details and negotiating with the Albanian parties, the ruling coalition had a deal in place. To get unified support from the Albanian Parties, language was included to make it clear that while citizens of the country would be considered “Macedonian” – that was a national phrase and not just an ethnic phrase – asserting that the Albanian, Turk, and Romani minorities would be recognized. The final vote saw all parties except the main opposition conservatives support the measure – though they saw defections as well. Defectors were promptly expelled from the party.

The measure passed with just 1 more vote than was needed. The measure needed 2/3 support to get past the opposition from the President.

Following the passage in North Macedonia, a final vote would be required in Greece. Before the vote, Greece’s Defense Minister, a member of the small Independent Greeks Party (a coalition partner with SYRIZA) resigned. This forced a no-confidence vote in the Greek Parliament to see if Prime Minster Alexis Tsipras still had a working majority. Tsipras won the vote by a narrow 151-148 margin. Greece, which has been seeing protests for months over the deal, continued to have clashes. Protesters and police clashed. Russia, opposing the deal as it would lead to another NATO state, pumped propaganda into the region to stoke fears. The biggest source of Greek opposition was a fear that allowing North Macedonia to keep the name would allow it to later claim it had to the right to the Northern Greece region of Macedonia (despite the agreement specifically ruling that out).

The Greek parliament went on to approve the deal 153-146 on January 25th. Of the votes, 145 came from SYRIZA and the other 8 came from Independent Greek defections and some independent members. With this, the deal was done! Just two weeks later, in February, North Macedonia was admitted into NATO. EU talks are in the works.

The State of North Macedonia Politics

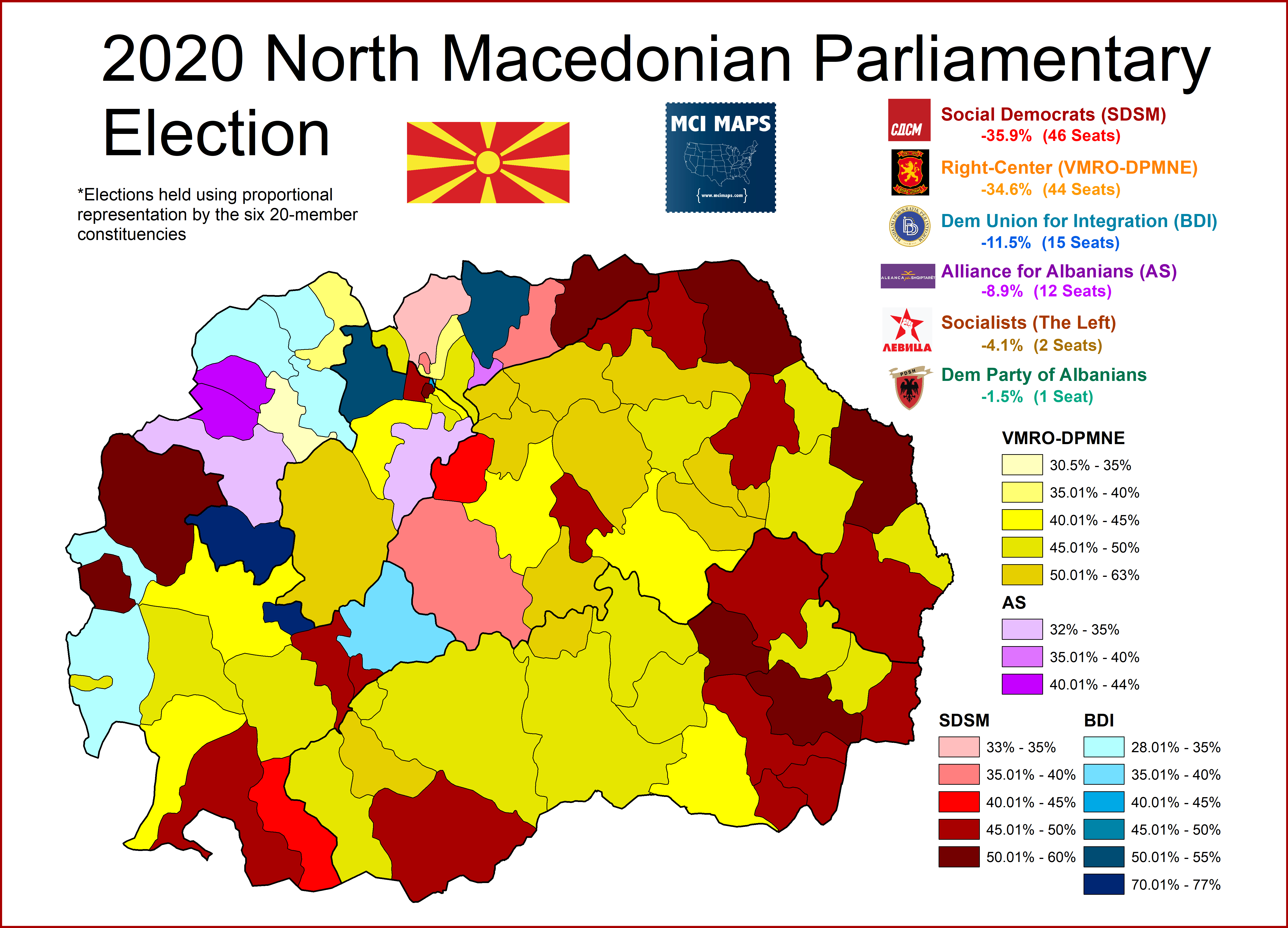

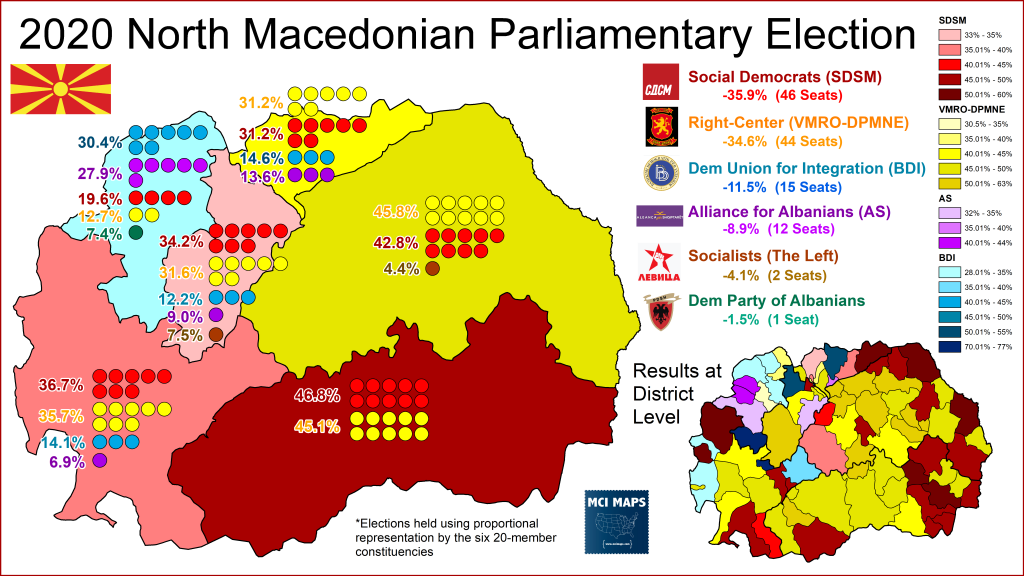

Macedonian politics is dominated by the fight between the Social democratic SDSM Party and the right-wing VMRO-DPMNE party. These parties fight for the majority ethnic Macedonian voters; while Albanian parties compete for ethnic Albanians. The Albanian Parties often play kingmaker when governing coalitions are needed. The country holds elections using proportional representation in six electoral districts.

As mentioned before, VMRO was hard-line against the name change agreement. Supporters are overall much more nationalistic and anti-Greece.

The 2019 Presidential election became a quasi-referendum on the name change. As mentioned, the outgoing President was strongly against the agreement. The VMRO candidate pledged a new referendum and to work to change the name. The SDSM wound up winning with 53% in the runoff. Since then, VMRO has softened their approach, still ranting about national dignity but not outright pledging to reverse the name change.

A few years ago, North Macedonia went through a political crisis that saw its conservative Prime Minister resign and subsequently fled to Hungary after being convicted of corruption. Fresh elections in 2016 saw VMRO narrowly win the most seats, but after months of negotiation, SDSM was able to form a coalition with several of the Albanian parties. The Albanian parties have their own right and left leanings but those do not always dictate which side they take. Rather, they fight for the interests of their community; which can often cross right vs left lines. The BDI (or DUI depending on who is writing the article) actually switched sides in 2016, siding with the left after supporting an older right-wing coalition.

2020 North Macedonian Election

Polls heading into the 2020 campaign showed a close race. Plenty of press coverage focused on if the name issue would cost the ruling coalition. Before the election, the BESA Party, which held 5 seats in the parliament, joined with the SDSM for the election. This move angered BDI/DUI, who argued for Albanian parties uniting. The election appeared to go smooth, though once polls closed a cyber attack did crash the elections website for several hours. When all votes came in, the left of center had narrowly won the most seats.

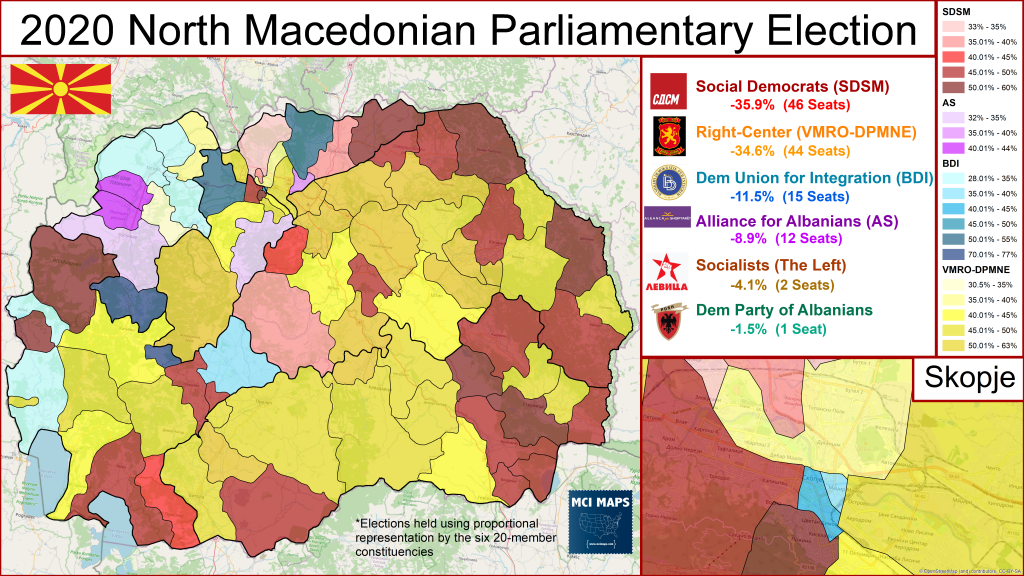

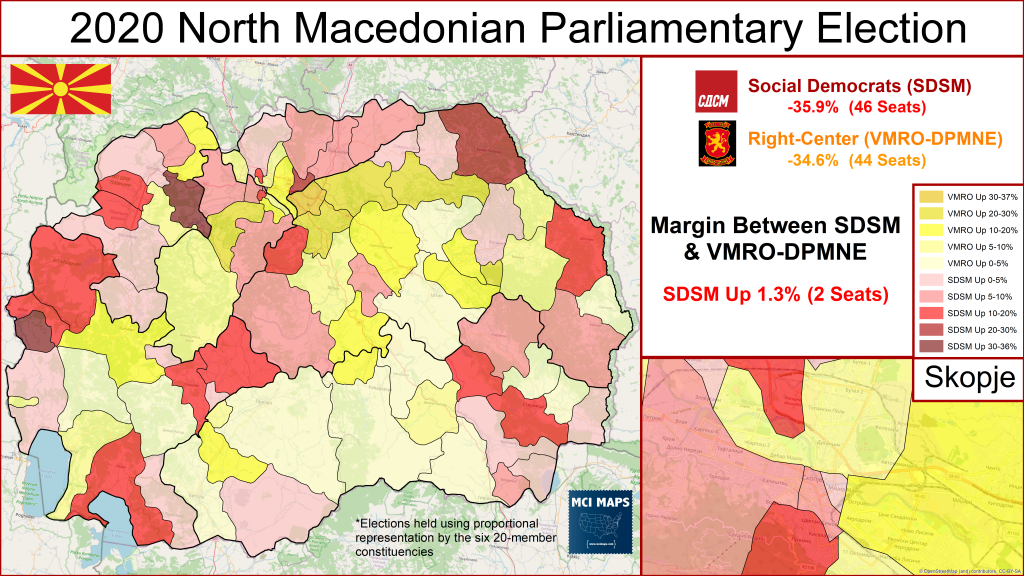

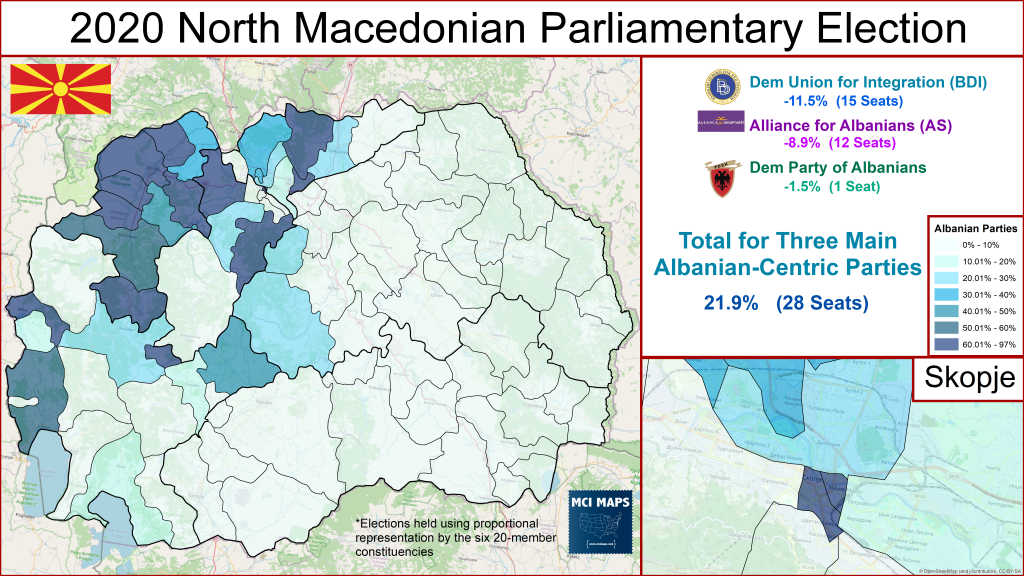

Both major parties lost seats. SDSM lost 8 and VMRO lost 7. The big gainers were the Alliance for Albanian’s (+9), the DUI/BDI (+5), and the Socialists entered the parliament with 2. Municipal-level results (which have no bearing on seat allocation) show the Albanian parties clustered in the north and west while VMRO does very well in rural areas in the middle and south. One key for SDSM was that they were ahead of VMRO in the Albanian areas, allowing them to net 3 seats over VMRO.

A map jut of SDSM vs VMRO better shows the center-lefts strength. Many areas that voted for Albanian parties saw the left outpace the right.

The breakdown of the three main Albanian parties by municipality shows the ethnic segregation in the county. Albanian’s are heavily clustered in the north and west. Outside of these areas, there vote share was non-existant.

With the elections over, coalition talks will begin. We could get a deal soon, or we could see it drag on for some time. It seems unlikely the name will be changed again regardless of the outcome, especially since it seems unlikely Albanian parties would back a move. But nothing can be ruled out. The results though are some vindication for the agreement. But forming a governing coalition will be a whole different matter.

Update – Coalition Formed!

A governing coalition has been formed. The Social Democrats have aligned with the Albanian-linked Dem Union for Integration and Dem Party of Albanians to form a narrow coalition government. This will allow Social Democrat Zoran Zaev to become Prime Minster again, and agrees to consider an Albanian Prime Minister in the last year of the coalition’s governing mandate.