As countries and local authorities rapidly work to contain the coronavirus pandemic, one outcome has been the delaying of several primary elections in the United States. Several Presidential primaries and congressional runoffs have been pushed to later in the summer as authorities work to keep people indoors. This has led to a debate about when elections should be moved and when they must move forward. While I will not try to offer my opinion on that complicated and tough issue, the debate did me of a time in history when a virus outbreak resulted in the delaying of election – Florida in 1822. The culprit: yellow fever.

Establishing the Territory of Florida

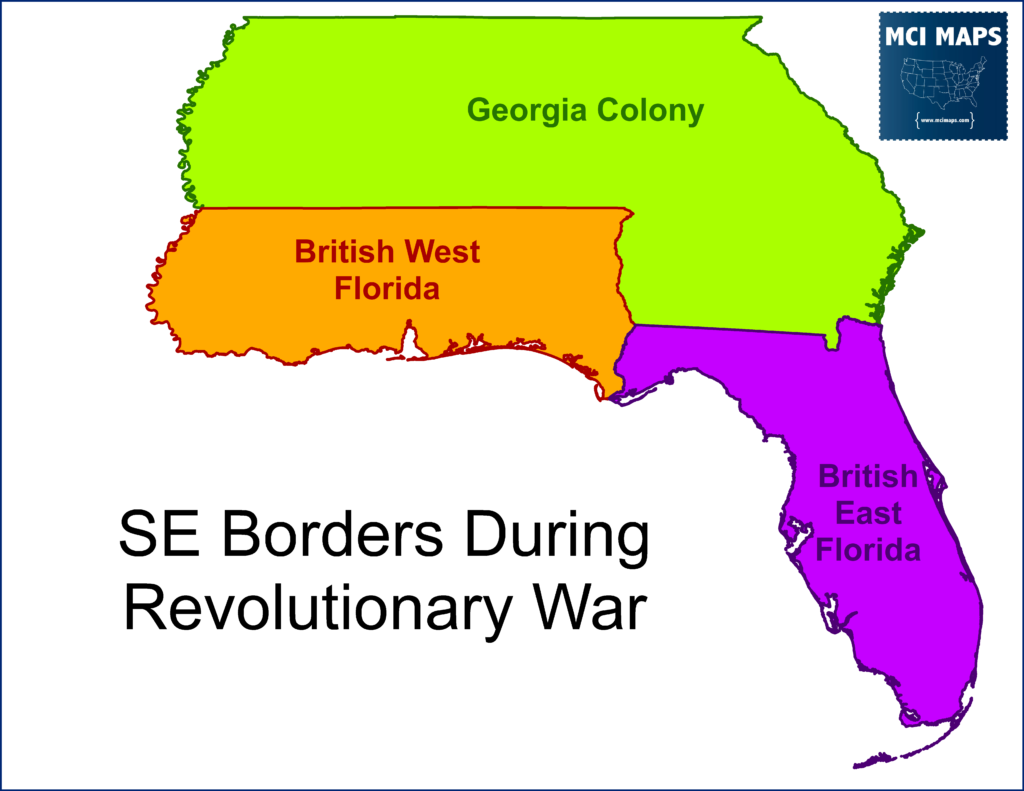

What we now know as Florida become a Territory of the United States in 1822. The land had traded control between the Spanish and British empires before this, with borders shifting further west and north at different points. During the Revolutionary War, Britain controlled what it then called the territories of East Florida and West Florida.

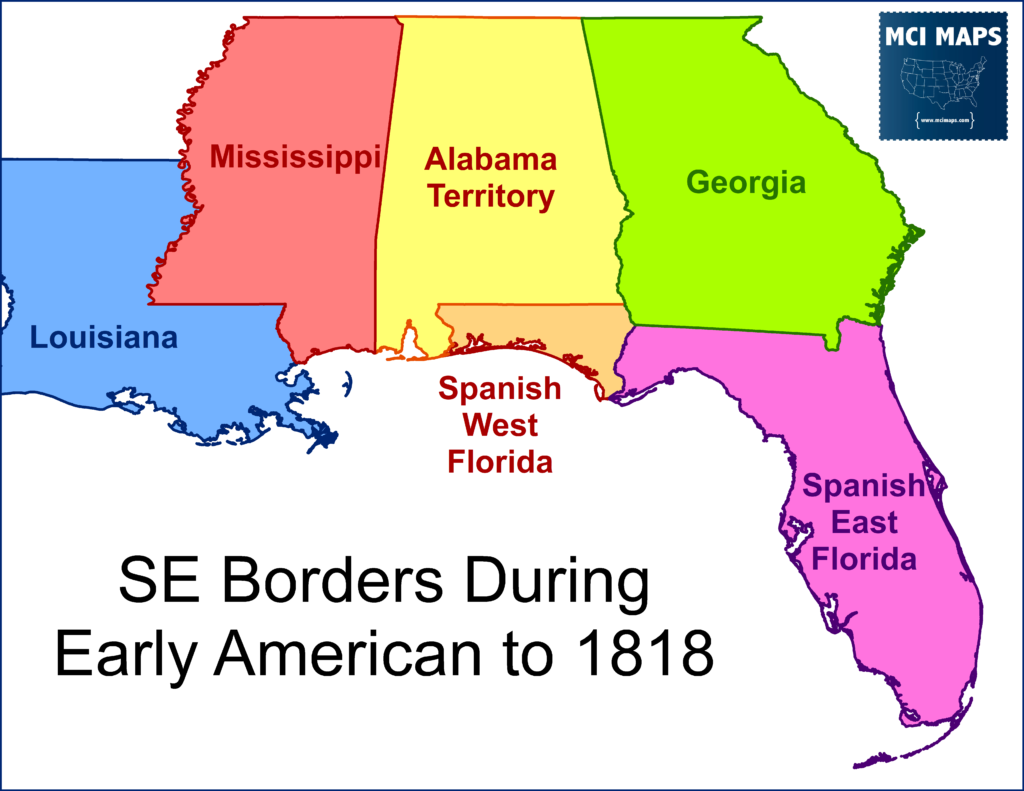

After several border changes and land being ceded to Spain, which you can read more about in a 2019 article I wrote, the borders looked like what is seen below.

While the Spanish controlled the land, they did little to administer it. Then, in 1816, the First Seminole War broke out. The conflict revolved around escaped slaves fleeing into the Florida territory and joining the native tribes that lived in the land. Raiding parties into southern Georgia gave the US the excuse it needed to engage in warfare. Andrew Jackson, already famous for the War of 1812, led campaigns into Florida. Jackson’s forces captured the city of Pensacola and the are became a major political base for Jackson and his political allies. His brutality during the campaign divided the administration of President James Monroe. Nevertheless, many hoped the troubles of the campaign would convince Spain to just cut its ties with the large and unruly swampland and sell it to the US, which it did. Jackson then became military governor.

The territory originally remained divided between east and west. Each territory had a base of population; Pensacola for the West and St Augustine for the East. In 1822 Congress established the “Florida Territory” with East and West United.

The Territorial Government

The establishment of a formal territorial Government meant the end of Jackson’s rule there – something he was more than fine with. The government was appointed by President Monroe.

- Governor William Pope Duval

- East and West Court Systems

- A thirteen member territorial council

The first meeting of Government would be in Pensacola, with the plan to hold a meeting in St Augustine the next year. At this time, the travel between cities could take more than a month and both sides would eventually call for finding a middle city to to make the capital – which would eventually become Tallahassee.

While Jackson no longer ruled the land, his influence in the territory remained long after he left. When he had initially arrived in Florida, several allies of his from the army, many of whom had political aspirations, came with him and subsequently stayed after he departed. Jackson was able to help the aspirations of his friends and through his efforts, 5 of the 13 members of the territorial council were his allies. These allies were….

- Richard Keith Call

- James Bronaugh

- H.M. Brackenridge

- Edgar Mason

- John Miller

In addition, the newly created Commission on Land Claims had several Jackson allies on it. This board sorted out which longtime residents had land rights and which lands would be open for sale. The commission was a good way to build alliances and gain wealth. The land office would become a major driver in territorial politics. Anti-Jackson politicians would often decry the land office and those associated with as the “Tennessee Speculators” and “The Nucleus.”

Divide in the Jackson Camp

It didn’t take long for a divide to emerge between the Jackson allies in the territory. The split was between Richard Keith Call and James Bronaugh – and it rested entirely on their respective ambitions. Both wanted to become the Delegate to Congress for the territory. The government was empowered to either chose a delegate via the legislature or by a popular elections. The agreement was that an election would happen and both Call and Bronaugh wanted the position.

Both Call and Bronaugh were Jackson men but they had different bases of support. Call was most popular with longtime residents of the territory, folks who lived there during Spanish rule. Bronaugh, meanwhile, was more popular with soldiers station in the ports and people flocking to the new territory.

These different bases of popular support resulted in the first session of the Territorial Legislature being dominated by setting the suffrage for who could vote in the delegate election. Call was at a disadvantage due to the fact Bronaugh had the broad support of the members to become President of the Council. The council was almost evenly divided on the suffrage issues and when session began in July of 1823, only 9 of the 13 members had arrived. Call was able to get a bill offering broad suffrage to longtime inhabitants passed by a 5-4 margin. Bronaugh and his most loyal backers opposed it. The key vote was Joseph White, who sided with Call on this issue but opposed all of Call’s efforts to restrict votes from military members and those just entering the territory. The vote to restrict military voting would fail by a 4-5 margin, with White being the switch. White would become Delegate to Congress years later and be a major political foe of Richard Keith Call for nearly two decades.

Back in Tennessee, Jackson made it clear he preferred Bronaugh for the position of delegate. He was close with both men, but advised the younger Call that he should spend his youth making money, getting married, and establishing himself. He felt Bronaugh could hold the western vote and stop any candidate running out of the east (where Jackson’s influence was limited) from winning. The east and west divide in Florida was a staple of the territory. The long distances between population centers, and the fact the land had been divided initially, meant the two sides had little communication or commonality with each-other. In the early days, the Jackson men were much more powerful in the west than the east. A divide in the Jackson camp meant a divide in the west, and vice-versa. Jackson’s letters show he disliked that Call and Bronaugh were feuding and wished for them to unite as one force.

As the session wore on, it appeared Bronaugh had the advantage. The suffrage bills included soldier and new resident votes, likely enough to stave off Call’s support with the longtime locals. Call was also under pressure from Jackson to unite around Bronaugh. But then…..

Yellow Fever Infects Pensacola

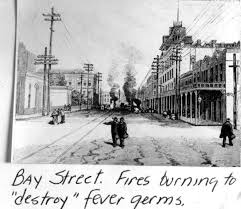

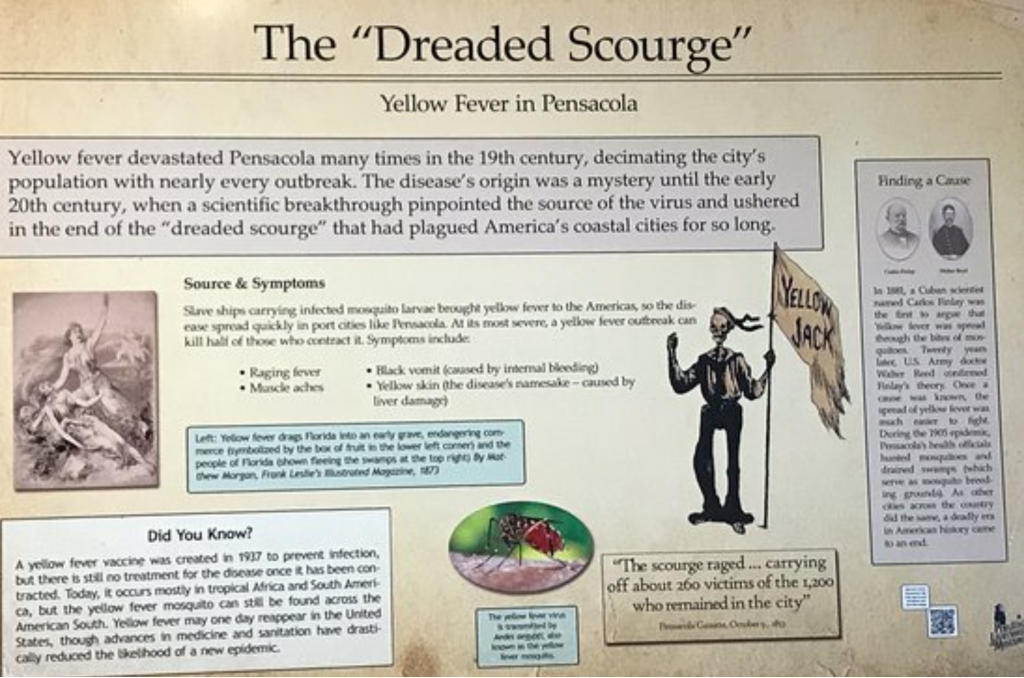

In the week of August 10th, 1822, Yellow Fever broke out in Pensacola. At first the warning came from medical professionals that the fever was beginning. However, calls for folks to leave the dense city saw push-back by the local papers and business owners who did not want the city to be labeled unsafe. Fires were lit in the town to “kill the germs in the air” – a common tactic at the time. Many argued that would be enough and no evacuation was needed.

These protests eventually did not matter when the rate of infection rapidly increased and the death toll began to rise. It ravaged the city, causing its population to fall by more than half. Hundreds fled the city and most of those who stayed died. Estimates of the population before the fever hit vary from 1,400 to 4,000 – but most agree that by the time it was over, only 400 or so remained in the city alive. Most fled, but hundreds died; civilian and military alike. The accounts of the fever are those of horror. Surviving correspondence show a town decimated by the disease. The outbreak killed many local political leaders and forced the legislative council to retreat to a barn 15 miles north of the city. The fever did not spare the council however. Joseph Conner, the Clerk of the Council passed; as did James Bronaugh himself. Jackson wrote to friends that he was dismayed by the loss of friends in a “dreadful calamity.”

Yellow Fever would ravage Pensacola many times before a Vaccine was discovered in 1937.

Image courtesy of TripAdvisor.

Aftermath

The terror of the fever resulted in all plans for an election in 1822 to be scrapped. Instead, the council appointed Joseph Hernandez of St Augustine to the post; with plans to hold an election in 1823.

Their was political calculus in this pick. Hernandez was a respected general who was born in St Augustine when the land was ruled by the Spanish and he had subsequently pledged his loyalty to the United States. He was a member of the Minorcan community in the city – a community made up of Greek, Italian, and Minorcan immigrants who had been brought to the Florida territory decades earlier and staged a revolt for their rights. He became the first Hispanic American to serve in Congress. The western political forces knew this appointment would be a nice political favor thrown to East Florida to make it happy; while at the same time give the West Florida forces time to regroup and settle on a candidate of their own.

The death of Bronaugh put Call in the strongest position to the western candidate in the election of 1823. He asserted the mantle of leader of the West Florida faction and faced little challenge. Thus, heading into the 1823 election, Call had the united support of the West.

The 1823 Delegate Election

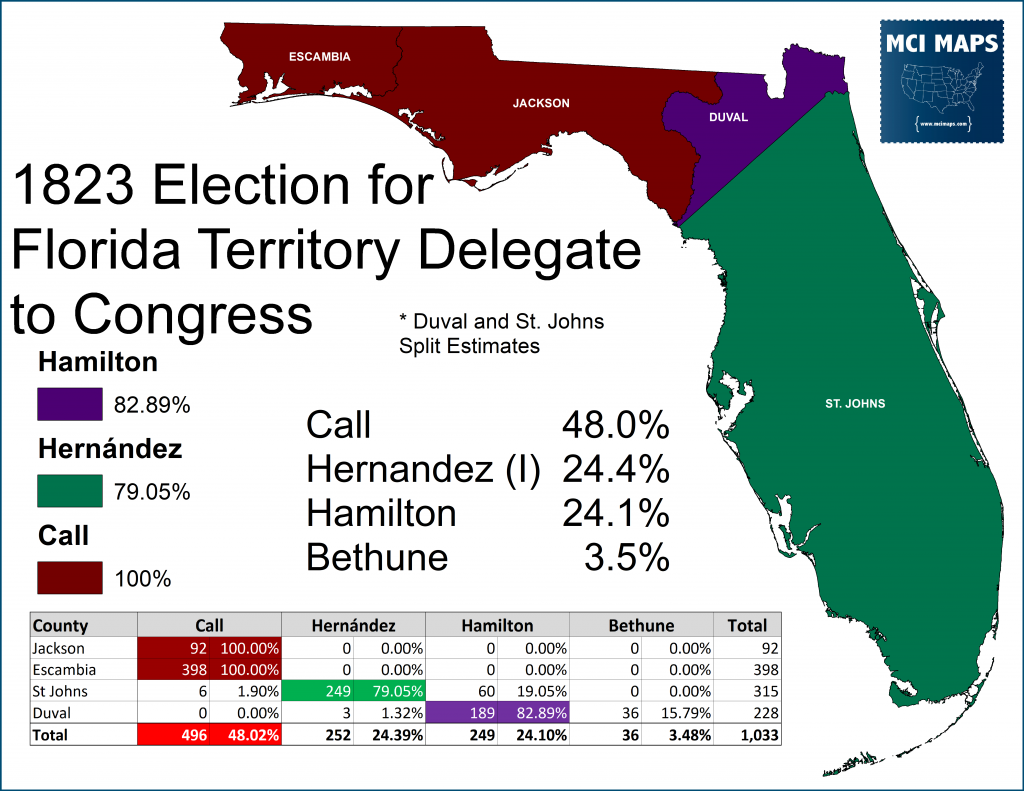

Things went perfectly for Call in 1823. Not only did he keep the west united around himself, but the east was bitterly divided. Despite being the incumbent, Joseph Hernandez still faced another candidate from the east; Alexander Hamilton Jr.

Hamilton, the son of the late founding father, was already a fixture in Florida politics. His tenure included service on the Land Commission and as District Attorney in the state. His role as DA, however, caused much ill will in the city of St Augustine. Hamilton offered his opinion as DA that all land owned by the Catholic Church in the area had really been property of the Spanish Crown under their rule, and thus the land now belonged to the United States. This led to a fear among the Minorcan population (many of whom were Catholic) that their local parishes could be confiscated. As a result, Hamilton was bitterly opposed in St John’s County – which was dominated by St. Augustine.

The election saw a united west go up against a divided east. Call secured 100% of the vote in Escambia and Jackson, while receiving just 6 votes west of the Suwanee River.

His 48% of the vote was more than enough to secure his spot as delegate. Runoffs never became a requirement in territorial Florida.

What If?

Call would only serve one term as delegate but would become a longtime political force in territorial politics all the way up until the civil war. He’d be seen as the head of the Jackson wing of the Florida political spectrum through the 1830s. The question that Florida historians have to wonder is… what if Bronaugh instead became the first delegate out of Florida and the leader of the Jackson. Would Call and Bronaugh have united? Would Call retreat from politics? Or would the Jackson men divide the west and allow East Florida to take a more dominant role in the early territory? We will never know.