Florida’s Proposed Amendment 3

This November, Amendment 3, also known as “All Voters Vote”, will appear on the Florida ballot. The backers of this amendment are phrasing it as a proposal for “open primaries.” However, this proposal does not propose an open primary in the classical sense; a system where voters pick which primary ballot they want to vote in, regardless of their partisan registration. No, this proposal would create a California-style “Top Two” system; where candidates for office appear on one ballot line, regardless of party, and the top two candidates advance to the runoff/general election. This would apply to all offices for state house, state senate, the cabinet, and governor. The advancing candidates could be from different parties or the same party. A state house race might see two democrats or two republicans advance depending on how the candidate split goes. Unlike Louisiana’s similar “jungle primary,” if someone gets over 50% in the first round, the top two still go to a runoff.

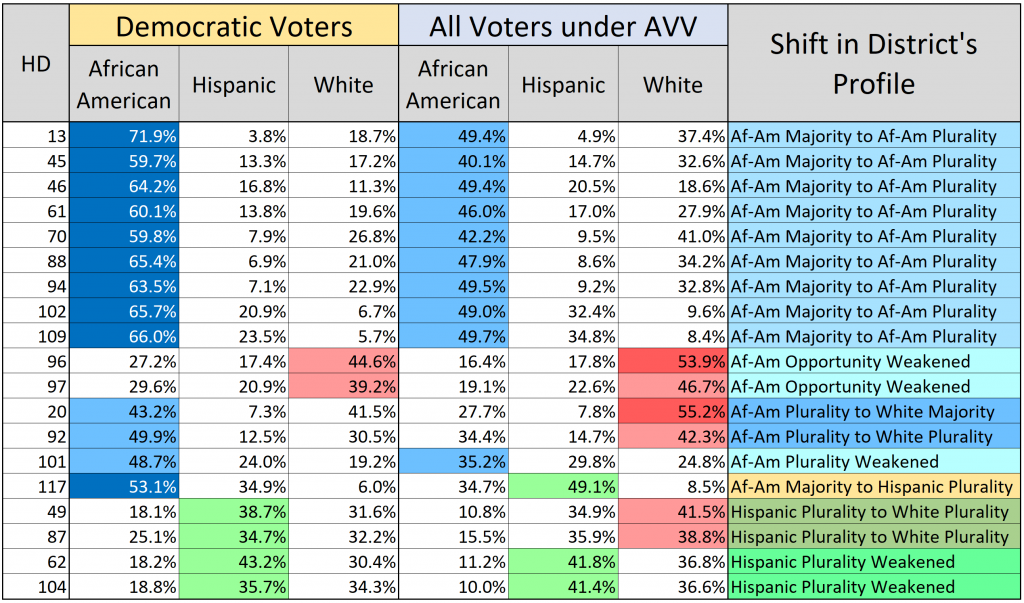

One unforeseen outcome of the system being passed is what it will do to the majority-minority and minority-access districts in Florida. My research finds that such a top-two system would severely impact the minority voting strength in many Florida districts and could have severe Voting Rights Act implications going forward. I dug into the numbers in Florida’s minority districts and the effect that “All Voters Vote” would have.

“All Voters Vote” Effects on Minority Districts

Amendment 3 will have a major impact on the makeup of minority districts in Florida. Florida’s House and Senate districts have been drawn to be both compact and equal in population; but also, to ensure the ability of minorities to elect candidates of their choosing. There are several metrics to determine if a district is likely to be controlled by a minority group. The voting-age-population is one metric. However, another is the political performance of the district. If a seat that is overwhelmingly likely to back one party, then the racial makeup of that party’s primary can and has been used in redistricting. This political performance profile is called a “Functional Analysis” and is a principle used in Florida’s redistricting process.

A functional analysis looks at the political history of a district, including its registration by party and race. In Florida, white voters on average have the highest turnout of any racial group. African-Americans often are 2nd in turnout, with Hispanic voters and other racial minorities much further back. As such, any breakdown of a district must consider these factors. For this study I use registration across the board and discuss past turnout as well. Turnout in primaries can be influenced by candidates and the contested nature of district; but a general rule of thumb is that turnout can easily wind up whiter than the registration figures indicate.

Effects in the State Senate

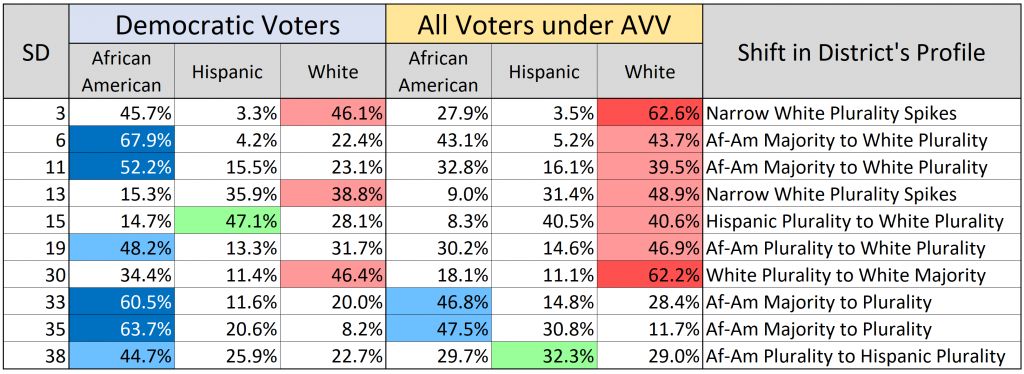

The data shows that if Amendment 3 were to go in effect, the results would be a severe reduction in the ability of African-Americans to control the outcome of several districts where they currently have members. Currently, six state senate districts are considered safe for the democratic party and have African-Americans as the largest voting bloc in the districts: 6, 11, 19, 33, 35, & 38. Five of these districts have an African-American state Senator, with 38 being the lone not to. Meanwhile, district 30, which has a 35% African-American share among democrats, also as an African-American Senator.

If Amendment 3 were to be implemented, the inclusion of the over-whelming white Republican voters would “bleach” these and several additional districts. While the African-American districts do not feature enough Republicans to swing the partisan balance of the seats; their overwhelmingly white makeup would cause many districts to lose their African-American voting edge. Primaries and runoffs could these Republicans swing races to white, moderate democrats over more liberal African-Americans.

State Senate Changes

Up to 10 Seats will see serious reduction in the political power of non-whites. All these seats are lean heavily Democratic and rely on primaries to advance the interests and power of African-Americans and Hispanics.

Under Amendment 3, no district is majority-African-American in registration. Districts 6 & 11 go from Majority-African-American to white plurality. Not a single district is African-American majority under this proposal. Hispanics lose control of the 15th, and a three-way even split emerges in the 38th. The situation in the 38th, however, highlights turnout dynamics. Despite Hispanics leading in and white voters being 3rd in registration; white voters made up the largest voting block in the 2018 general election.

Three other districts also see major changes that effect minority voter strength. The 3rd is close to having an African-American plurality, but it jolts to a solid white Majority under Amendment 3. The 13th goes from Hispanics having a sizeable minority share of the electorate to seeing a much larger gap with whites. Finally, the 30th seeing its 34% African-American Democratic primary share fall to 18%.

Let’s look at a few districts as examples of these changes

Senate District 11

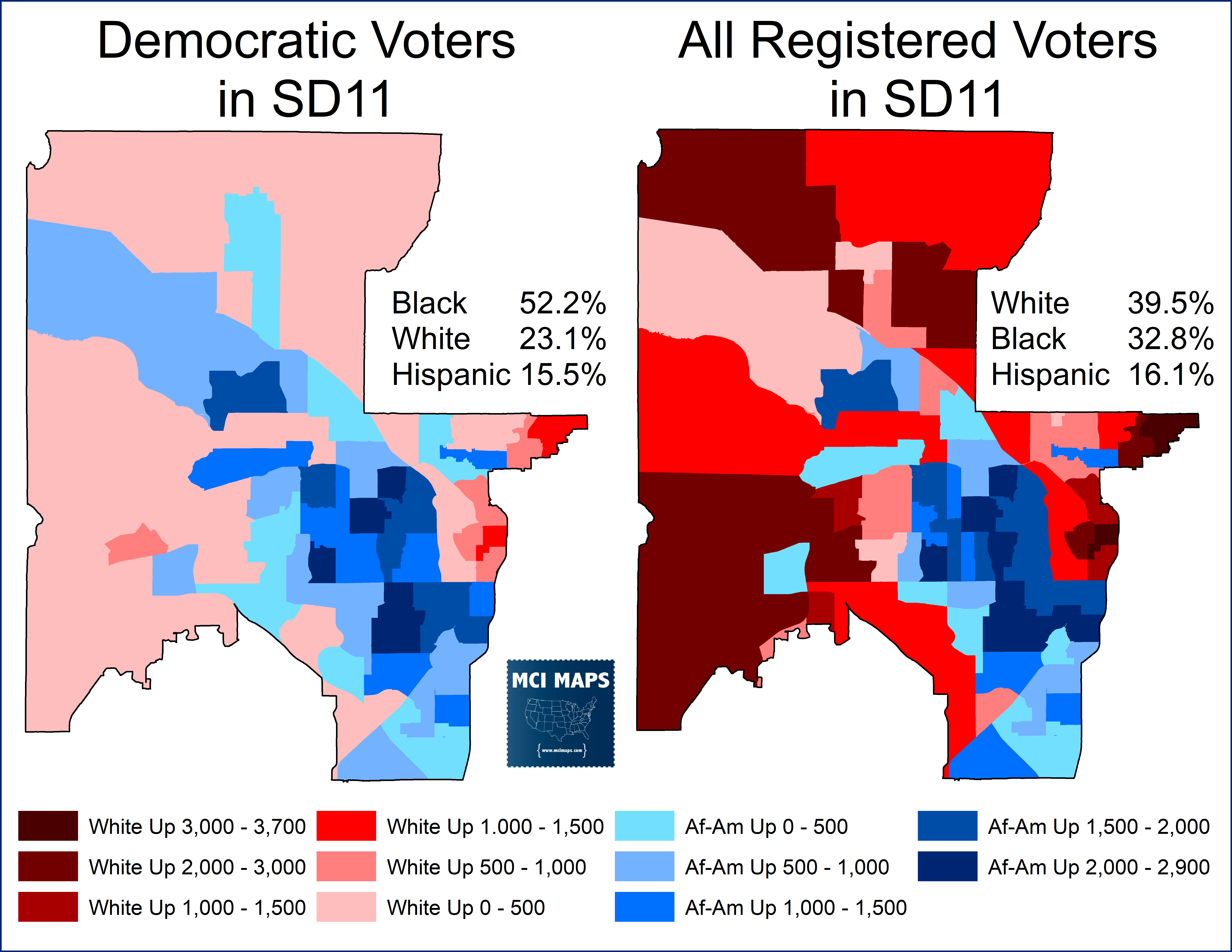

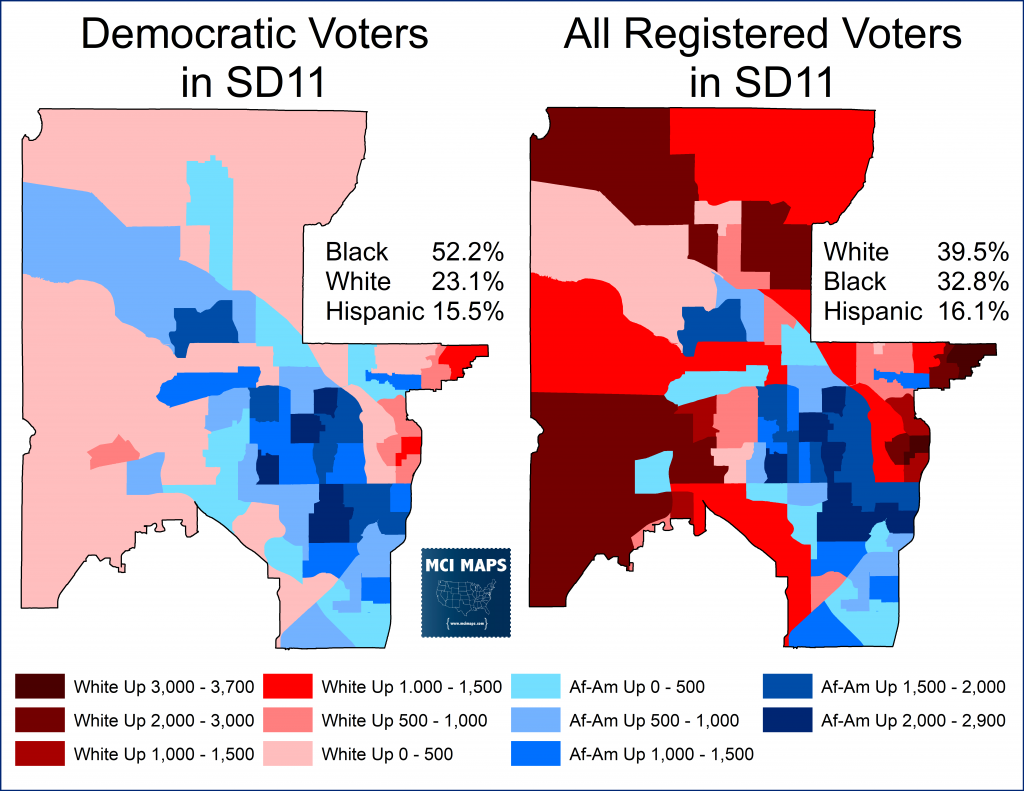

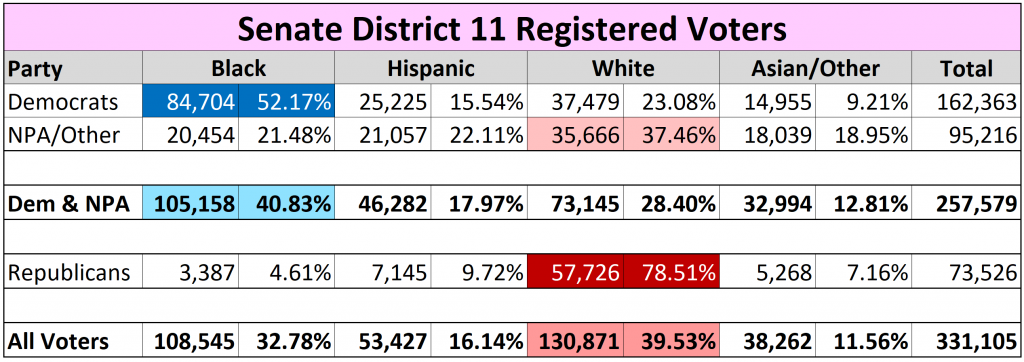

Senate District 11 is a majority-minority seat based around Orlando and NW Orange County. The district overwhelmingly leans Democratic, giving Democratic candidates like Hillary Clinton, Andrew Gillum, and Bill Nelson all over 60% of the vote. The registered Democrats of the district are 52% African-American, effectively giving the African-American control of the district. However, under Amendment 3, white voters would outpace African-Americans 39%-37% in the primary and general.

The reason for this massive shift in voting power is the inclusion of Republicans in the primary electorate.

Independent voters in the district are split among many racial groups, and a semi-open primary for Democrats and non-partisans would still see African-Americans be the largest voting group by 12%. However, the inclusion of Republicans, who are near 80% white, would “bleach” the electorate. Any runoff between a white democrat and African-American democrat would be very tough for the African-American community to hold.

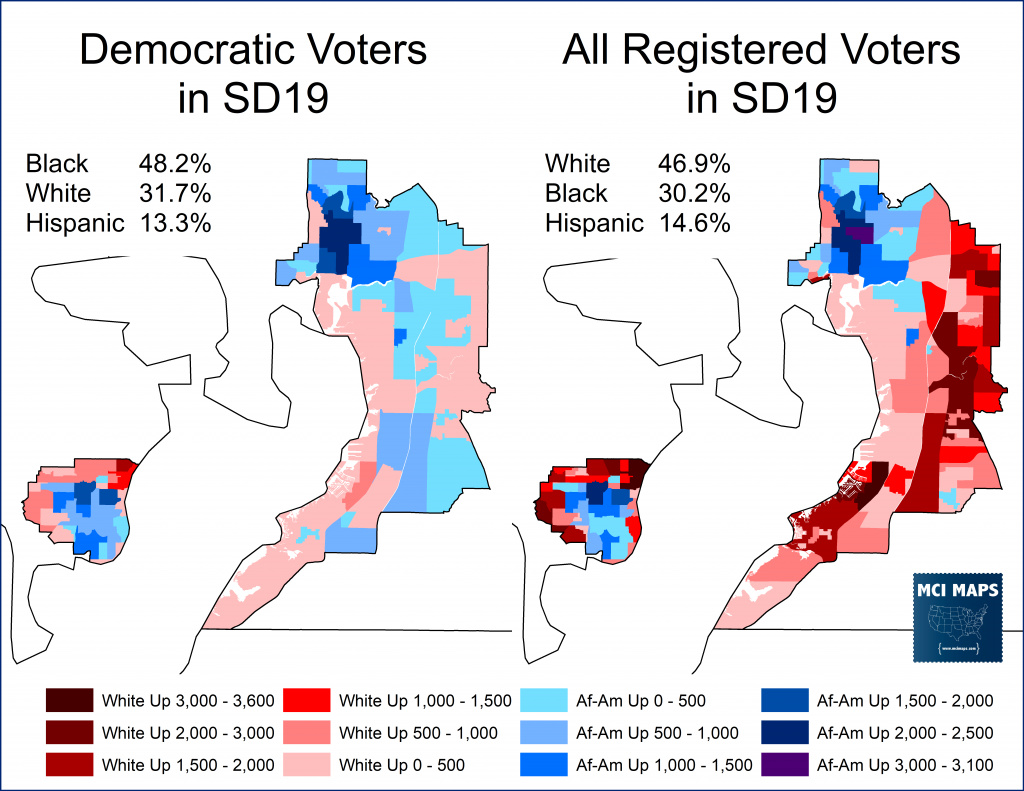

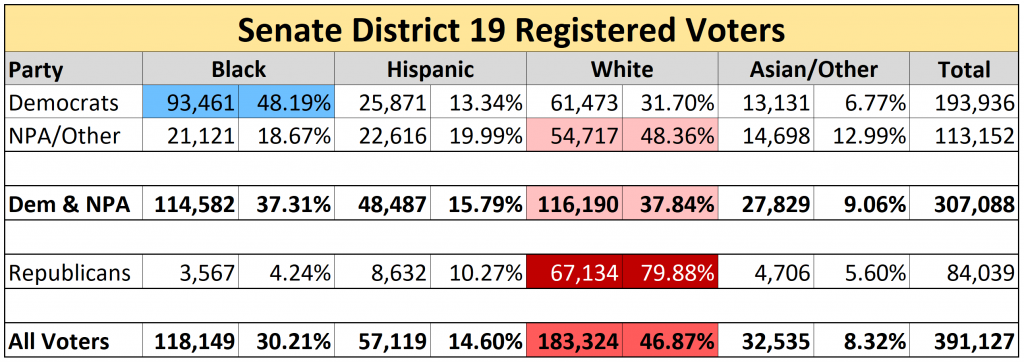

Senate District 19

State Senate District 19 is a well-documented and litigated district in the Tampa Bay area. Since the 1990s, a district has crossed the Tampa Bay, linking African-American voters in Tampa and St Petersburg in order to create a seat likely to elect an African-American member. The current district is 48% African-American among democrats, and like SD11, is safe for any Democrat running. Amendment 3 would radically alter this district, giving white voters a 17% advantage over African-Americans.

The issue here is the same as the one seen in SD11, the near-80% Republican electorate bleaches the seat. Independents and Democrats would create a near-perfect-split.

The effects of this change would erase 30 years of African-Americans being able to elect a candidate of their choosing from the Tampa Bay area.

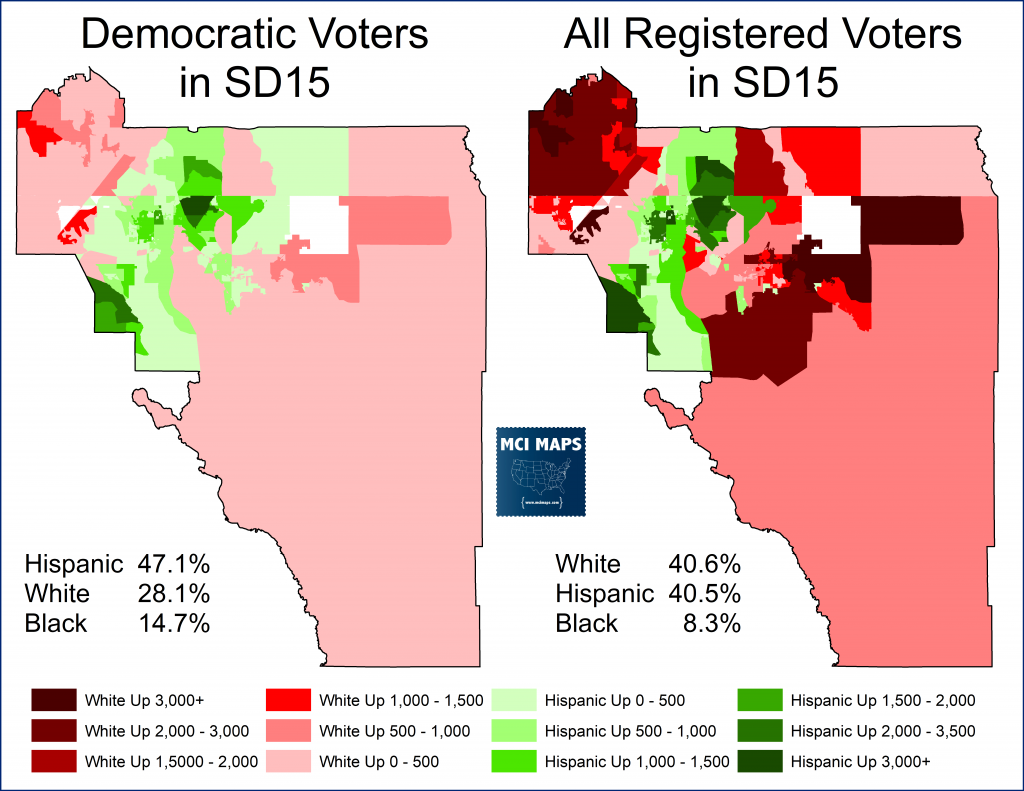

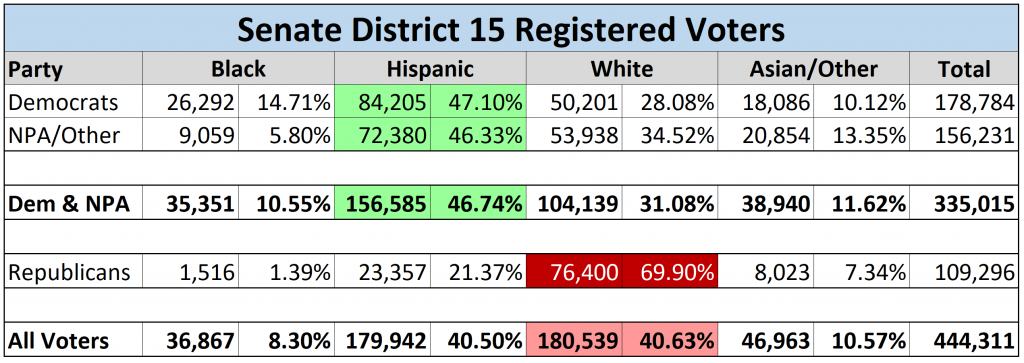

Senate District 15

African-American districts are not the only seats that would be adversely impacted by this measure. The Orlando and Kissimmee based SD15 is meant to be a Hispanic-access district. This district, currently held by Hispanic State Senator Victor Torres, has Hispanics at 47% of voters, with White voters at 38%. Thanks to well-documented turnout deviations between Hispanics and White voters, its also critical that a district with the aim of giving Hispanics an opportunity to elect a member of their choosing have a larger registration advantage. Amendment 3 would result in a near perfect split between whites and Hispanics.

Again, the culprit is white Republicans. Independents in the area are almost as Hispanic as the Democratic electorate, but Republicans are 70% white.

These results have an even worse impact for Hispanic voters than the registration figures show. In 2018, Hispanic turnout was only 43%, compared with 62% for white voters. As a result, the November electorate in in SD15 was 48% white, 33% Hispanic. If a November runoff wound up between two democrats; one white and one Hispanic – then the seat would not be decided by Hispanic voters.

Effects in the State House

Like the state senate, Amendment 3 would have major negative effects on the ability of non-whites, especially African-Americans, to control seats in the state house. A large swath of safe-democratic house seats lose their African-American primary majorities and others see white voters emerge to the top of the voting pool. In total, over 15 districts see shifts in major changes in control of the voting power of the district: most at the expense of African-Americans.

- African-Americans and Hispanics each lose voting control to whites in 2 districts a piece

- African-Americans also lose their majority of the primary in 10 districts.

Some notable districts that stand out….

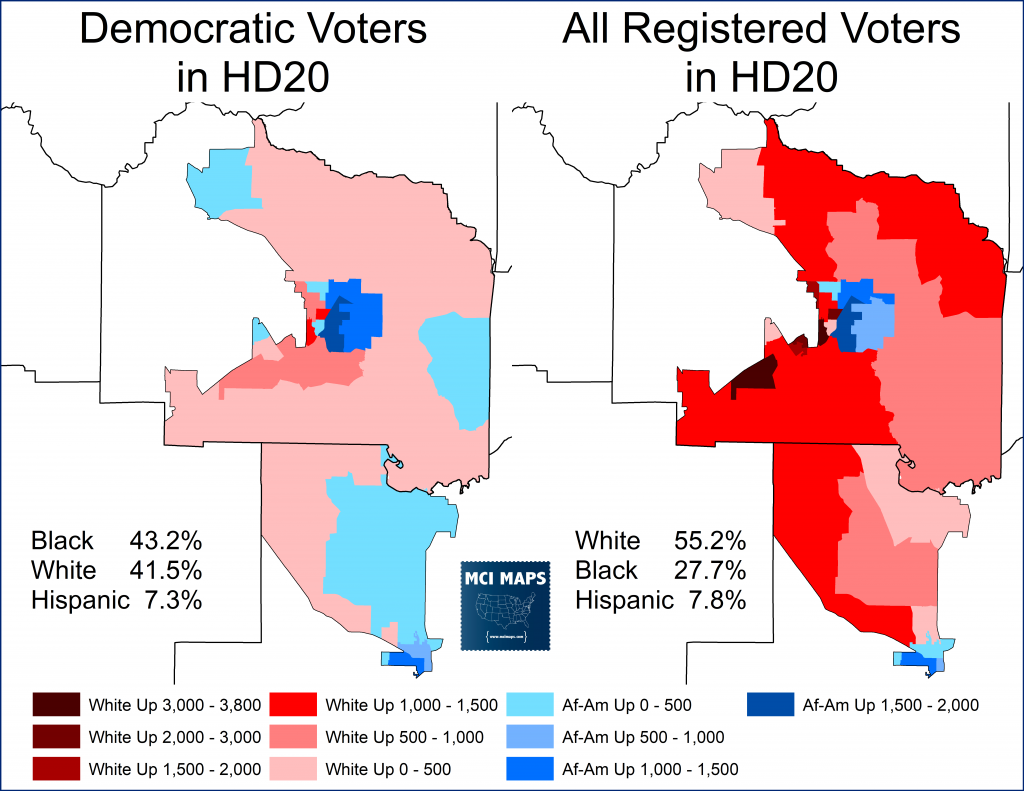

State House District 20

District 20 is designed to connect the African-American communities in Gainesville and Ocala. It has long been represented by an African-American democrat despite the primary being close between African-Americans and whites. However, under the Amendment 3 scenario, the primary and runoff electorate would be overwhelmingly white. This is largely thanks to rural white republicans being included, who are very unlikely to back an African-American.

A runoff between a white democrat and white republican would for sure elect the white Democrat. Any African-American would have to rely on advancing with a Republican, allowing partisanship to win the day.

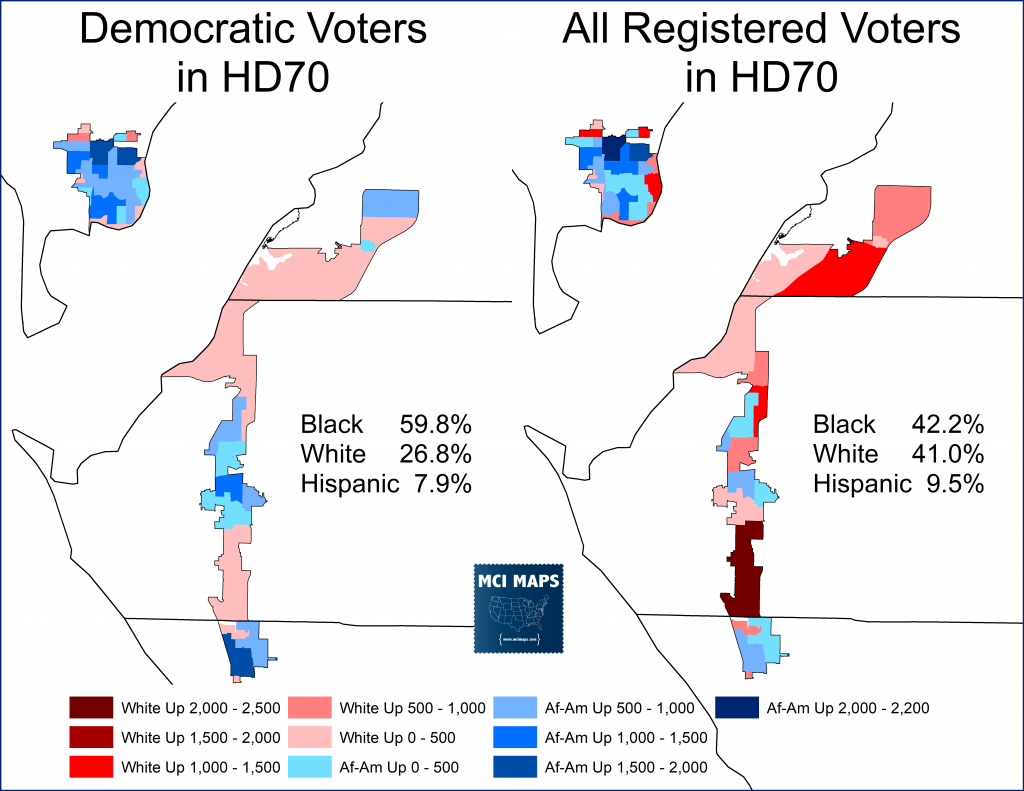

State House 70

District 70 is already held up as prime example of potential gerrymandering. The district’s odd shape is a result of a goal to grab as many African-American voters as possible. The result is a democratic electorate that is solidly African-American. Reform proponents have long pointed out the high African-American share means that some appendages down into Sarasota and Manatee aren’t needed. However, if Amendment 3 passed, the margin between white and African-American voters narrows considerably.

This narrow margin makes the heated argument over the shape even greater and would cement the clear political gerrymander of the district (packing in Democratic voters in Sarasota).

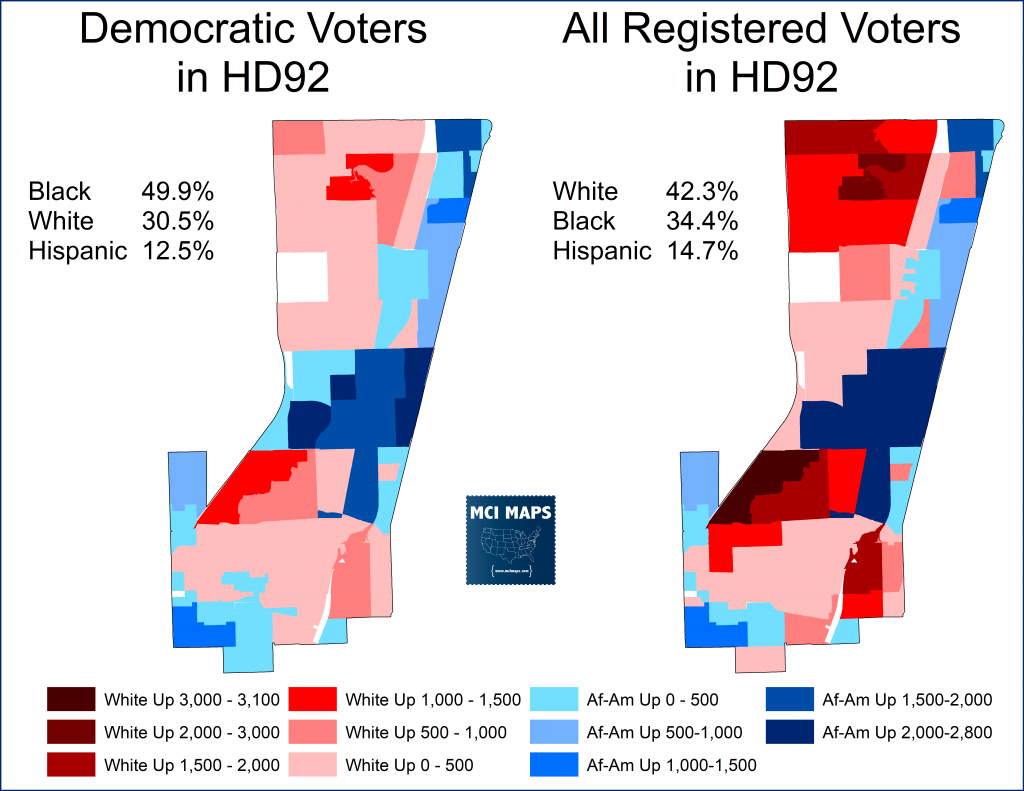

District 92

District 92 is right on the cusp of being majority-African-American in a primary. It connects African-American voters in Broward County, while at the same time adhering to major roads and natural boundaries. The seat become plurality-white, however, under the Amendment 3 scenario.

As a result, African-Americans would lose their control of the district, or mapmakers would be forced to redraw lines in more jagged and jigsaw ways to maintain African-American control.

Conclusion

Amendment 3 claims it is good for all voters in Florida and often relies on the talking point about non-partisan voters being left out of the primary process. However, as the data shows, the consequence of this plan is not that NPA voters will have a say, it is that a flood of white GOP voters in safe Democratic districts will “bleach” seats and seriously erode the voting power of African-Americans and Hispanics. The results will be a sharp reduction in lawmakers of color, or a return to bizarre and snake-like district lines. Many states balance the issue of ensuring minority districts with different levels of open primaries; like allowing NPA voters to choose a ballot line. The Amendment 3 plan is not a small step but rather a massive overhaul of Florida’s voting system that will have massive casualties when it comes to minority representation.