Every 3rd Monday of January, America celebrates the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr; the face of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Dr King’s commitment to non-violence as a way to protest the Jim Crow south were instrumental in turning the nation’s attention toward the struggle of African-Americans to secure basic rights in many states in the nation. Growing up, every child (hopefully) is taught about King and the civil rights movement. His “I have a Dream” speech captivates students and serves as inspiration, but also a cruel reminder of our nation’s flawed past. King’s assassination in 1968 made him a martyr for the the cause of civil rights in America and he is known world-wide. As we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr Day again, this article takes a look at the fight to cement his legacy, and the legacy of the civil rights movement, with a formal holiday.

The Push for a Federal Holiday

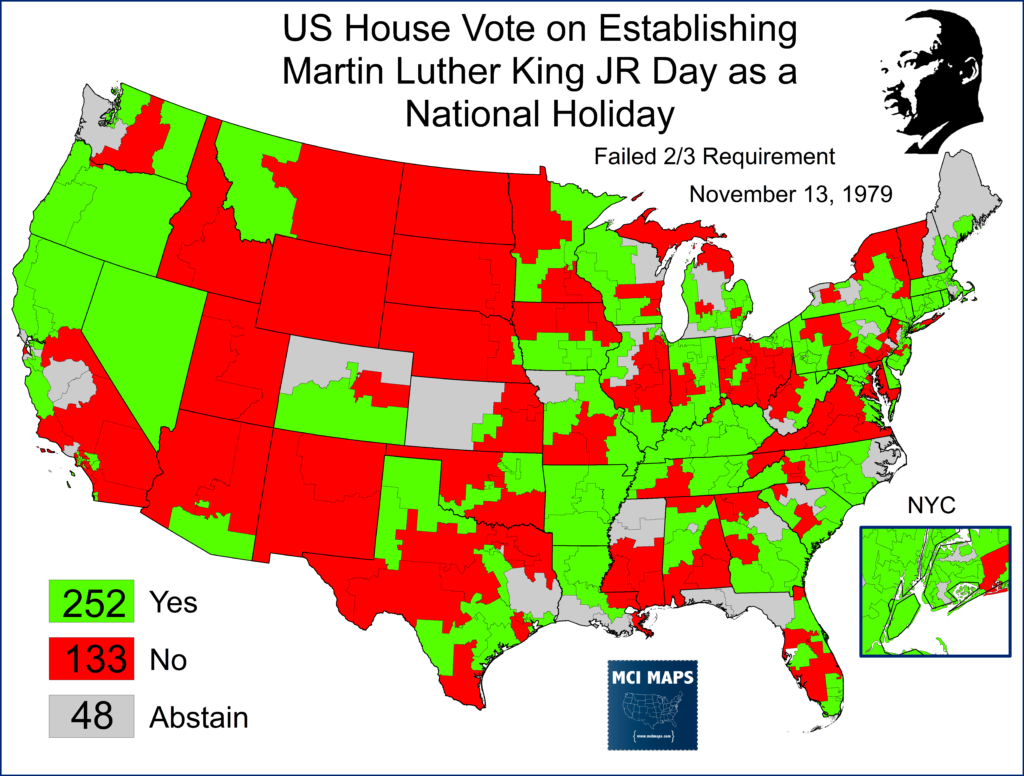

Talk of a holiday for Martin Luther King Jr began the very year he was assassinated. Massachusetts Senator Edward Brooks (a Republican who was also the Senate’s only African-American Senator) introduced a bill as did Democratic Congressman John Conyers. Bills were introduced in subsequent years but never got votes. The first vote happened in 1979; which was the 50th anniversary of King’s birth. King’s widow led a massive grassroots lobbying push and Jimmy Carter expressed support for the holiday. Congress engaged in major debate on the proposal in committees and finally on the US House floor. Opponents of the bill largely focused on the bill being a paid holiday and the costs associated with that. The nation’s weak economy at the time gave this argument life. Critique of King himself was reserved to a handful of hard-right members. The bill was taken up under suspension of the rules (meant to limit debate and the normal process). Suspension of the rules was used to prevent amendments from being proposed that could have passed and weakened the bill (like making it a non-paid day). This, however, meant a 2/3 vote was needed to pass. The bill got a solid majority but was just 5 votes short of 2/3rds passage. Roll call is here.

Just about every state had split delegations on the issue. Big cities like NY, Chicago and LA saw their delegations back the measure and rural areas were less supportive.

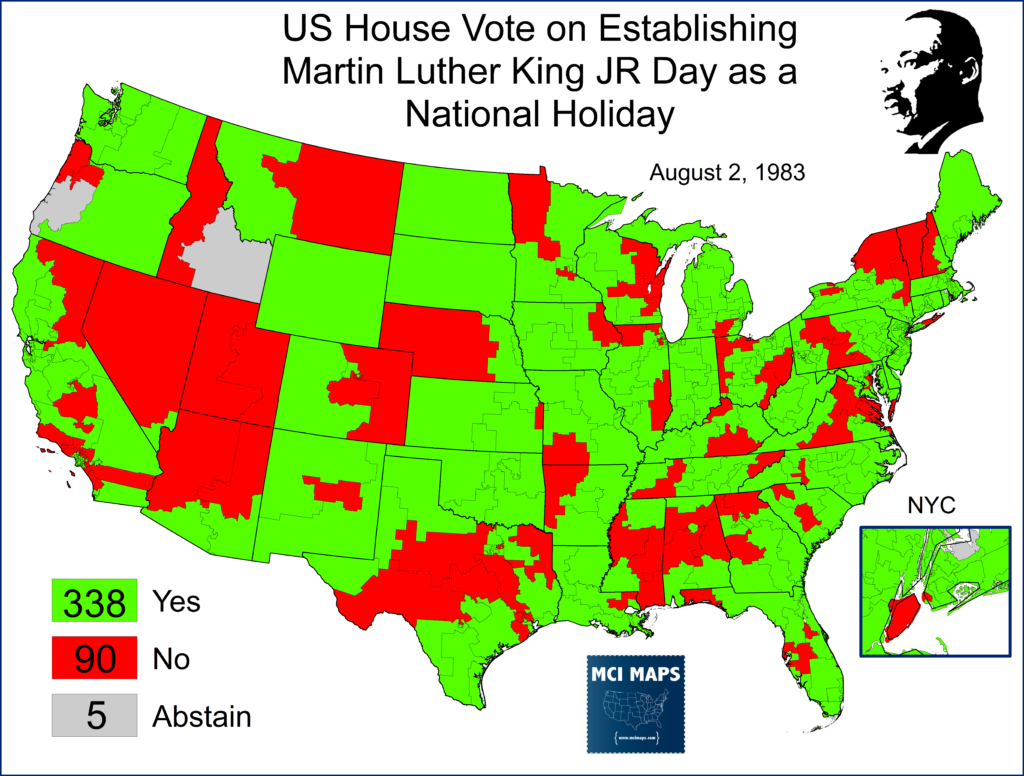

The effort to pass stalled for a few years but was renewed in 1983, the 15th anniversary of King’s assassination. Support for the holiday was much more broad this time around. Many prominent Republican leaders backed the bill as did the Democratic Speaker, Tip O’Neal. Reagan had expressed hesitation on the bill but did not fight against it as it worked through the process. A final vote came in August, where it passed overwhelmingly. Roll call here.

Opposition was again reserved to some more rural areas while support was otherwise strong across the board.

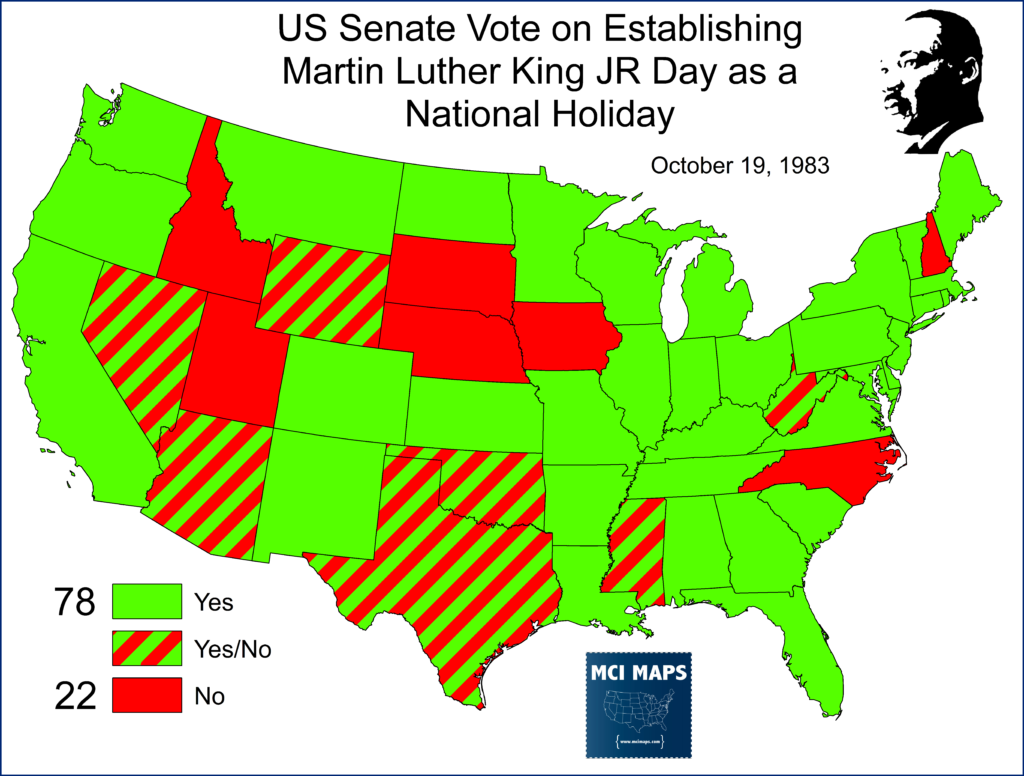

The Senate debate was very heated. The measure clearly had a majority support, but a filibuster by North Carolina Senator Jesse Helmes; by far the biggest racist the United States Senate as seen in some time. Helmes finally agreed to stop delaying the bill from moving forward in exchange for being able to push other bills through to a vote and to be allowed to push amendments to the King bill. Each amendment was rejected but debate grew heated. Helmes passed out the FBI reports on King (which were part of a character assignation attempt by J Edgar Hoover). Senator Ted Kennedy decried Helmes’ attacks on King as “inaccurate and false” – which actually stirred controversy because its against Senate rules to question the integrity of a Senator. New York Senator Patrick Moynihan of New York threw the FBI packed on the ground and decried it as garbage. New Jersey Senator Bill Bradely said Helmes spoke for the past that the nation overcame.

The GOP-controlled Senate passed the bill 78-22. Roll call is here.

With the bill passing both chamber of Congress, Reagan tepidly agreed to sign it. Then true to his nature he gave a good speech at the signing ceremony where he praised King (thus making him seem like more of a supporter than he actually was). An excellent detailed breakdown of the push for a federal holiday can be

The Push for State Holidays

When a federal holiday is declared, it only effects federal agencies and employees. State and local employees, as well as schools being open or not, are determined by state and local policy. Subsequently, as the federal government debated a federal holiday, states were debating state holidays.

Timeline for State Holidays

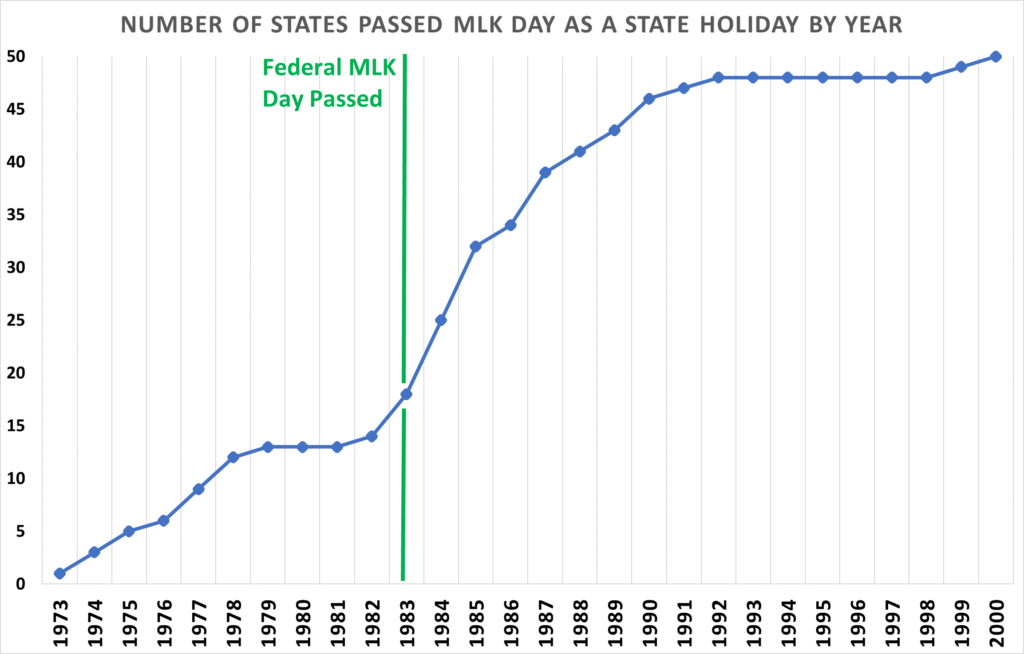

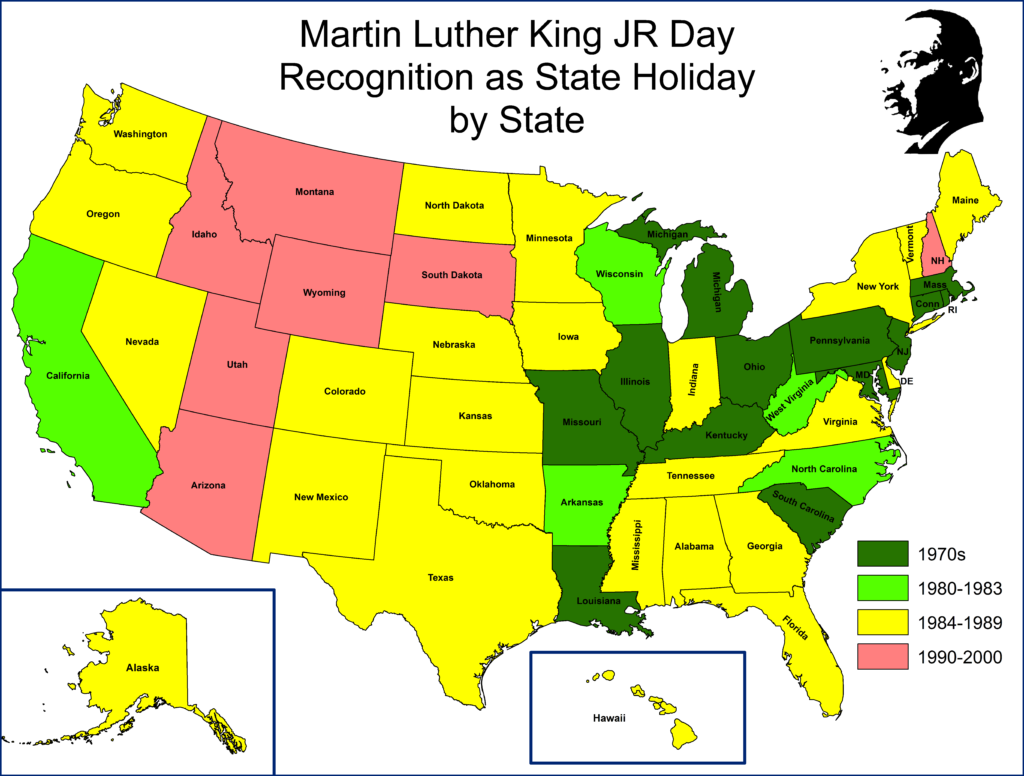

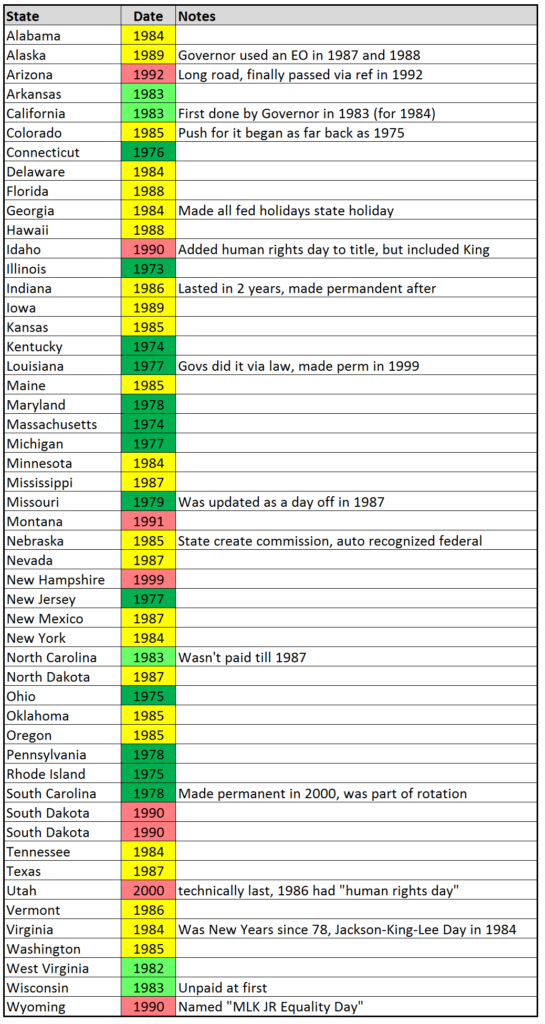

State holidays for Martin Luther King actually predate congress passing the federal holiday. The first state to make a state holiday for MLK was Illinois; with then-state rep Harold Washington (and future Chicago Mayor) pushing the bill through. After that, almost each year saw more states add the state holiday. Midwestern and New England states were the most common to add the holiday in the 1970s. However, a couple southern states did as well. Louisiana passed a law in 1977 allowing the Governor to proclaim a holiday year-by-year (it always happened) and South Carolina passed a law allowing employees to chose MLK day from a list of other holidays as an option for taking the day off. Both states would codify the 3rd Monday as a guaranteed holiday in 1999 and 2000.

Once the federal holiday passed, the numbers jumped with each year and several states passed laws to comply with the new law. An important note, my years are based on when the state passed the law (but often that meant the first celebration wasn’t till the next year).

The south didn’t hold out as much as I would have expected. Granted, many of these chambers where held by Democrats (albeit conservative Democrats). In these chambers the primary pushers of the legislation where African-American state representatives. In cases like Louisiana and South Carolina legislation passed easily. Meanwhile, in Mississippi African-American lawmakers had to use procedural delay tactics on other bills to get the white democratic leadership to even hear their MLK bill in committee. Several states had to try over multi-year periods; often with one chamber passing and another not.

The most common argument against any King holiday bill was money. Many states didn’t want to add another paid day off due to budget constraints. Many newspaper ope-eds also decried the the number of days government employees were getting off (which is still criminally low compared to Europe). This op ed from Kentucky highlights the sentiment well.

Those damned state employees and there 11 paid days off a year. The most common solution was to remove a different holiday from the roster. Many southern states combined the MLK proposal with Robert E Lee Day, already a paid holiday in the region (more on that later). States like Missouri and Illinois initially passed it without a day off – however all states now offer a day off. To make matters simple my “year of enactment” counts for days off or not.

No doubt racism played a role in some opponents of the holiday. However, for the most part those sentiments were not outspoken. Senator Jesse Helmes or Arizona Governor Edward Mecham stand out as the most the obviously racist opponents. Critics of the holiday because of King specifically relied on old attacks of “communist links” (part of Hoover’s character assassination) or that one man alone shouldn’t be honored (a common argument in the mountain west states where King’s impact was minimal). Overall whether a representative vote for or against the holiday can’t be enough to determine their racial attitudes. Other factors or statements must be examined as well.

By the end of the 1980s only a handful of states had not passed the holiday. Most where in the west, where low African-American population and King’s influence not being as strong, led to delays. Utah passed a “Human Rights Day” in 1986, which I don’t count. Others, like Idaho, passed an “Martin Luther King-Civil Rights Day” combination – which I do count. This line graph shows the progression of states passing a state-level holiday. A big jump did occur once the federal legislation passed.

New Hampshire is often regarded as the last state to pass a state holiday, doing so in 1999. However, I give the award to Utah do due their Civil Rights Day not actually mentioning King. They passed a revised law in 2000 honoring King.

An animation of each state’s passage by year is below.

The map below color-codes the states based on the time-frame they passed the legislation. As I mentioned earlier, the western mountain states stand out while the Midwest and southern New England stand out on the opposite end.

The subsequent table below lists each state and when they passed the holiday. I also included any important notes I came across. When it comes to paid/unpaid I am sure I’m missing some details.

Southern Confederate Holidays Combined with King’s

When talking about Martin Luther King Day in the south, it is often pointed out several states celebrate King’s Holiday along with Robert E Lee’s birthday as well. Of course, Lee being the major general for the confederate army (who wasn’t nearly as anti-slavery as revisionist historians like to claim) this is often seen as a major insult. Currently two states still celebrate a “King/Lee” day: Alabama and Mississippi. Arkansas separated the days last year and Virginia did so in 2000. In other states, like Florida, there is a Lee holiday but its been moved to a different time of the year and is largely ignored despite being on the books. Many may think Lee was attached to King’s holiday as a way to placate white southerns or insult King supporters. Believe it or not, the combination was often orchestrated by African-American lawmakers.

When the push for a state-level MLK holiday was going on in the south, Lee’s Birthday was already a state holiday in this region of the country. Lee was born January 19th and states had set up the 3rd Monday as a paid day off. The 3rd Monday was the same date the federal MLK holiday was set for. As the push for an MLK holiday went on, African-American lawmakers, the most earnest pushers of the legislation, offered a compromise to simply attach King to the Lee holiday. This removed the worry of the cost of an extra day off and many southern whites saw it as an appropriate balance. In Alabama, African-American State Rep Alvin Homes, who pushed the bill for MLK day through, remarked that without the Lee holiday already existing, passage would have been much tougher. In Virginia, State Rep Douglas Wilder, who would go on to be the nations first African-American Governor, pushed a MLK holiday bill through in 1984 (an early bill had been vetoed by the last governor) that combined King’s birthday with the Stonewall Jackson/Robert E Lee day already in effect.

These combinations of King and confederates were a compromise at the time due to these holidays already existing. With time these holidays have been separated (in many cases the confederate holidays moved and made non-paid). It is obvious these combinations are very problematic and easily insulting. However, for many in the 1980s they were a method of getting a foot in the door for the holiday.

Arizona’s Controversy

No state is more synonymous with the push for state-level MLK days than Arizona. In late 1986, outgoing Democratic Governor Bruce Babbit created a paid MLK holiday by executive order to coincide with the federal holiday. However, the new governor, Republican Evan Mecham, reversed the decision. This and subsequent events propelled Arizona into national news over the holiday. The controversy lasted years and is worth examining here.

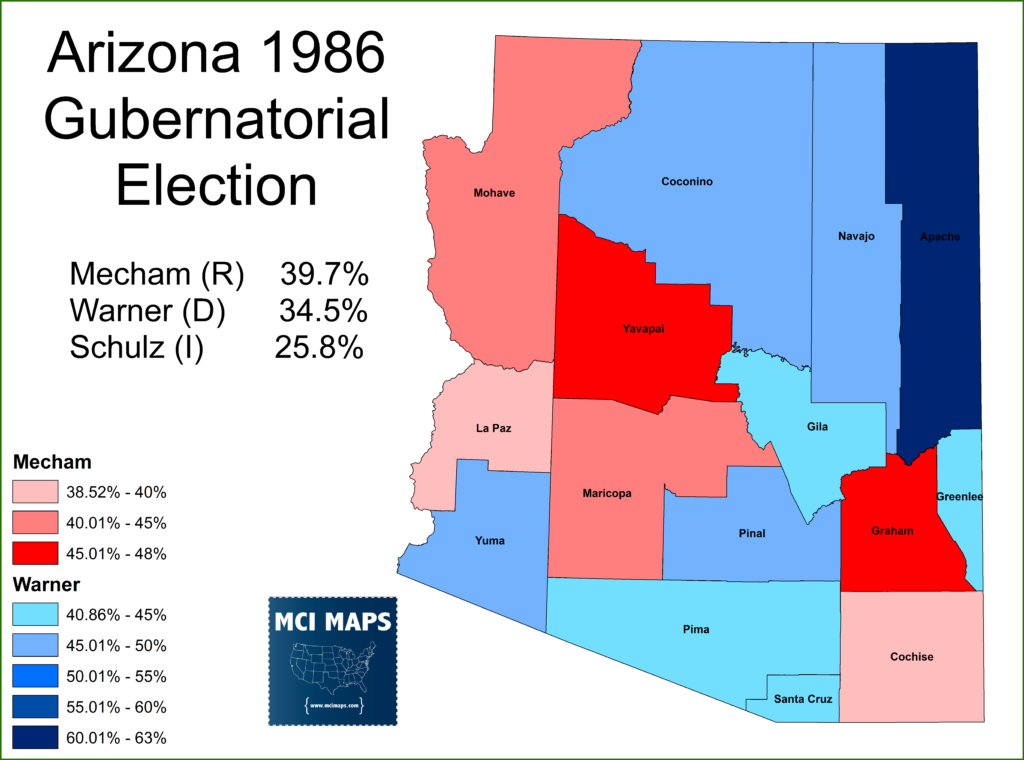

Mecham’s history is important to understand. He was an extremely conservative, racist, and controversial figure in Arizona politics. He had been a state senator in the 1960s and lost a US Senate race while running on an anti-UN and anti-limiting school prayer platform. He ran for Governor four times, only winning the primary once and losing all four times. He had the backing of the John Birch Society. His 1986 win was thanks to a string of good luck. First, the growing population meant many voters in 1986 were unaware of his perennial candidate past. Second, his main primary opponent, the current Speaker of the State House, didn’t spend all his money in the primary and low turnout allowed Mecham to score an upset win thanks to his fierce hyper-conservative supporters. Mecham would have been a sure loser in the 1986 General, but a major split in the Democrats helped him. The Democratic candidate was Carolyn Warner, the State’s Superintendent of Education. Originally, the front-runner for the nomination was Bill Schulz, a real-estate developer who had almost beat Barry Goldwater in the last US Senate election. However, Schulz pulled out due to family illness but then jumped back in as an independent two months before the general. He spent $11 million and split the Democratic field. While he aimed to win, he came in 3rd and the split Democratic base allowed Mecham to win with 40%.

Mecham’s time in office was filled with controversy. It is easy to call him the Donald Trump of the 1980s. Controversies of his included

- Rescinding the MLK holiday

- Telling black leaders they needed jobs, not a holiday

- Making racist comments about the shape of asian’s eyes

- Referring to African-american children with “pickaninny” – a racial slur

- Several ethical and criminal appointments

- Claimed he was being spied on

- Attacks on the press

His tenure was non-stop controversy. A recall petition was begun to remove him from office and the signatures were gathered. However, before the election could happen, the state legislature (controlled by Republicans, keep in mind) impeached him for lying about finances during the campaign. This meant the Secretary of State, a Democrat, became Governor.

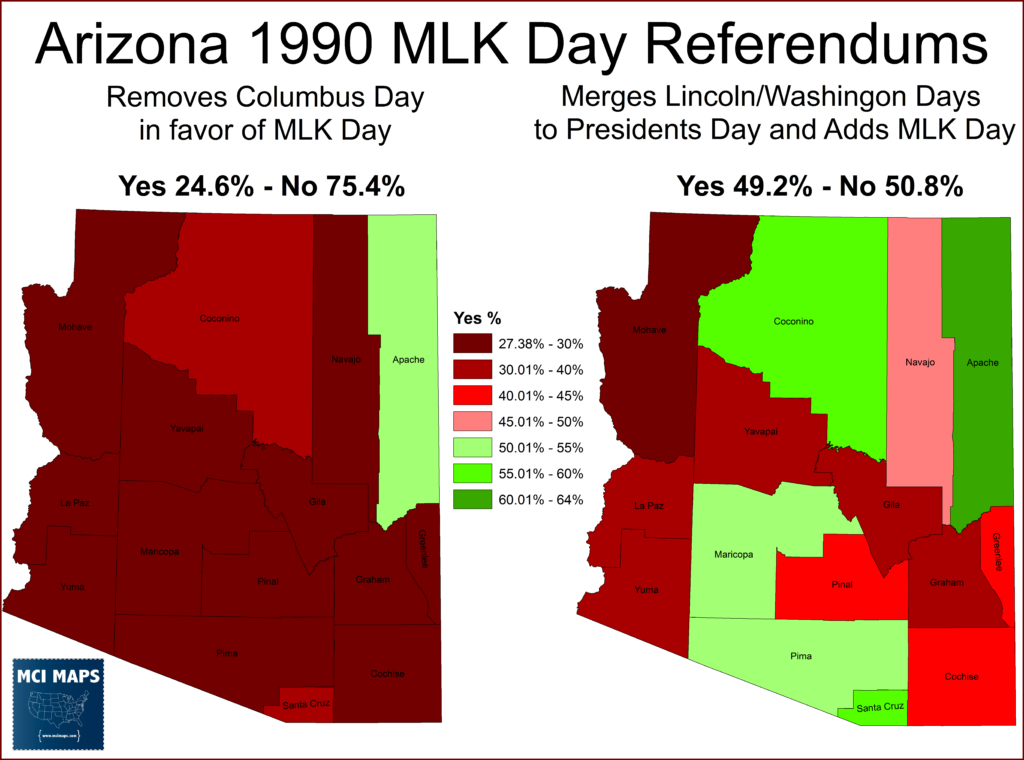

The legislature passed a bill to eliminate Columbus Day as a paid holiday in order to have a paid MLK day. However, conservative opponents, with Mecham as one of the leaders, collected petitions to force a referendum on the bill. The legislature subsequently passed a different bill to keep Columbus day but merge Lincoln and Washington’s Birthdays into one paid holiday. Instead of cancelling the referendum, the courts ruled it would go forward. Opponents then drafted petitions for the second law as well. So both were on the ballot in the 1990 midterm.

The more popular, and campaigned for, proposal was the combing of Washington and Lincoln’s birthdays. However, both proposals failed.

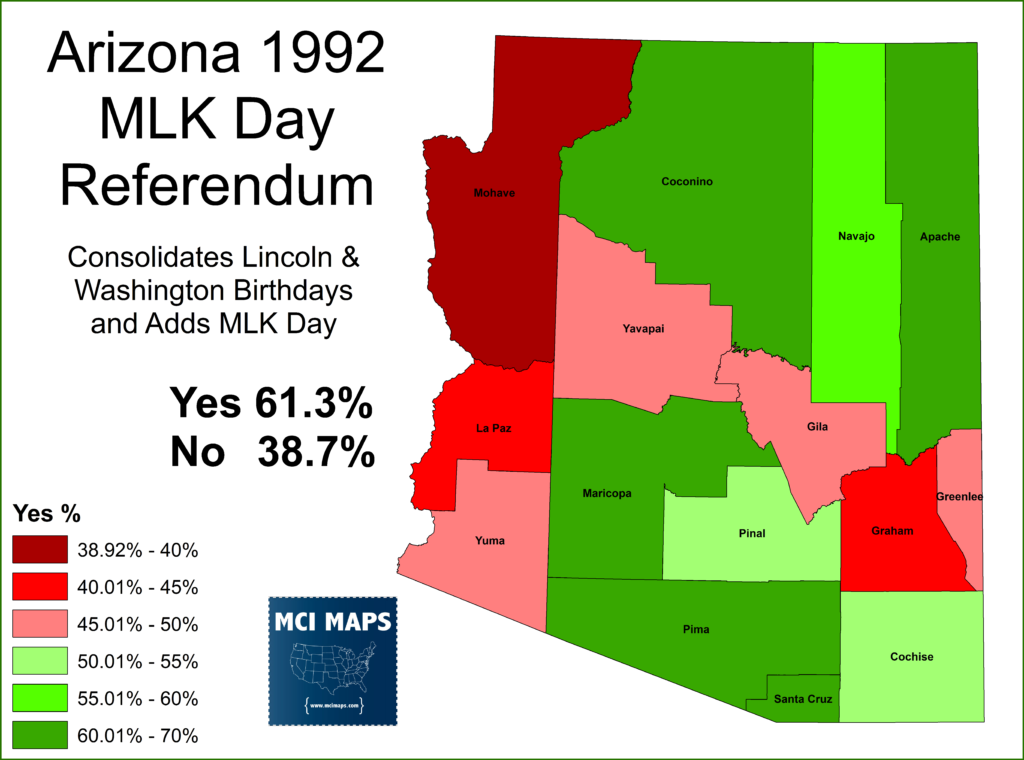

The result was the planned 1993 Super Bowl being pulled from the state (these threats were made before the election).

The economic hit felt (other businesses refused to move to the state and the colleges had recruitment issues) resulted in another legislative bill, which the legislature put to the people in 1992. The bill did the same thing as 1990, consolidating Lincoln and Washington’s birthdays in favor of a new paid King holiday. This time the measure easily passed.

Turnout was much higher in 1992, though there are likely many who voted no in 1990 who voted yes in 1992. By the end the state was eager to shed its image as racist. Whatever misgivings about King specifically getting the day were cast aside in the name of sheer economics.

Arizona remains the only state that held referendums on the King holiday.

Conclusion

The decision to pass a holiday honoring Martin Luther King was not about just one man. The holiday is meant to represent the civil rights movement and support the notion of non-violent protest. King was an inspirational figure and solid leader of the movement in the 1950s and 1960s. The holiday serves as an opportunity for America to remember its past and learn from it.