On July 4th, 1945, the nation celebrated as it finally became a united country for the first time since before the Civil War. The Chattanooga Free Press proudly proclaimed “The Stars and Stripes waved in a gentle breeze today above Dade County Courthouse, last citadel of the Confederacy.” Dade County, Georgia has finally rejoined the union after seceding over slavery in 1860, a month before the rest of Georgia followed suit. The legend has it Dade County left Georgia, became the “State of Dade” and never formally rejoined Georgia or the union once the war was over.

The legend of the state of Dade goes as follows: State Representative Bob Tatum gave a speech to the Georgia House in the session following Lincoln’s election; demanding the state immediately secede from the Union. When the legislature did not immediately pass a secession resolution, Tatum returned to Dade County and in a meeting of its citizens, the county seceded from the State of Georgia and became an independent nation/state. The county then formally “rejoined” the union in 1945.

Of course, from the Civil War till 1945, Dade County always was considered part of the union. It participated in government and at no point did it act like some survivalist outpost claiming freedom from tyranny. Rather, the 1945 event meant to be an informal celebration of Dade renouncing its former secession. The legend of Dade leaving the union BEFORE Georgia gives it a unique place in Civil War history. The only county to secede before its state seceded.

There is just one problem with this legend; its complete fiction.

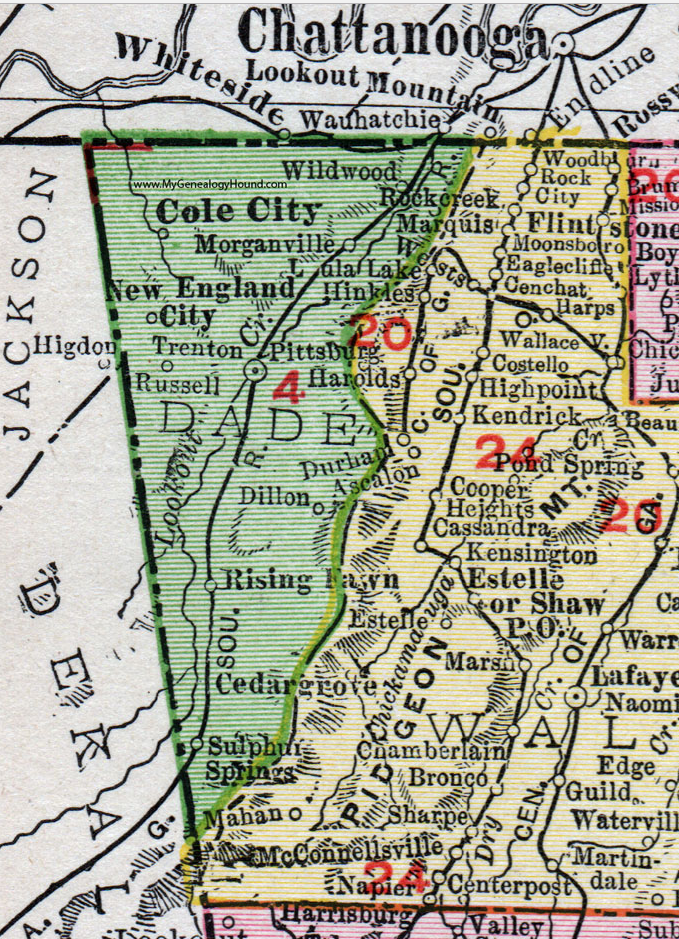

Dade County, Georgia

Dade County is a small and unassuming county in Georgia. It makes up the Northwestern edge of the state and only has a population of around 16,000 people.

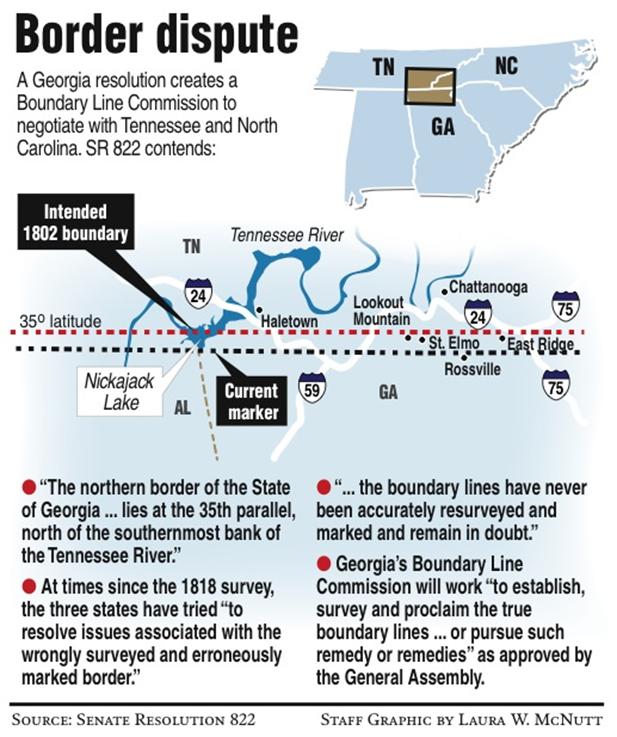

These days the county is more known as the site of the long-running feud with Tennessee over the rights to the Nickajack Lake. The issue stems from the fact Georgia’s Northern border was incorrectly survey in the early 1800s, placing their border below the 35th parallel it should have been at. Had the border been done correctly, the lake, and hence water rights that go with it, would belong to Georgia. For a growing Atlanta metro area, this access to water is a major source of debate. Map from Times Free Press.

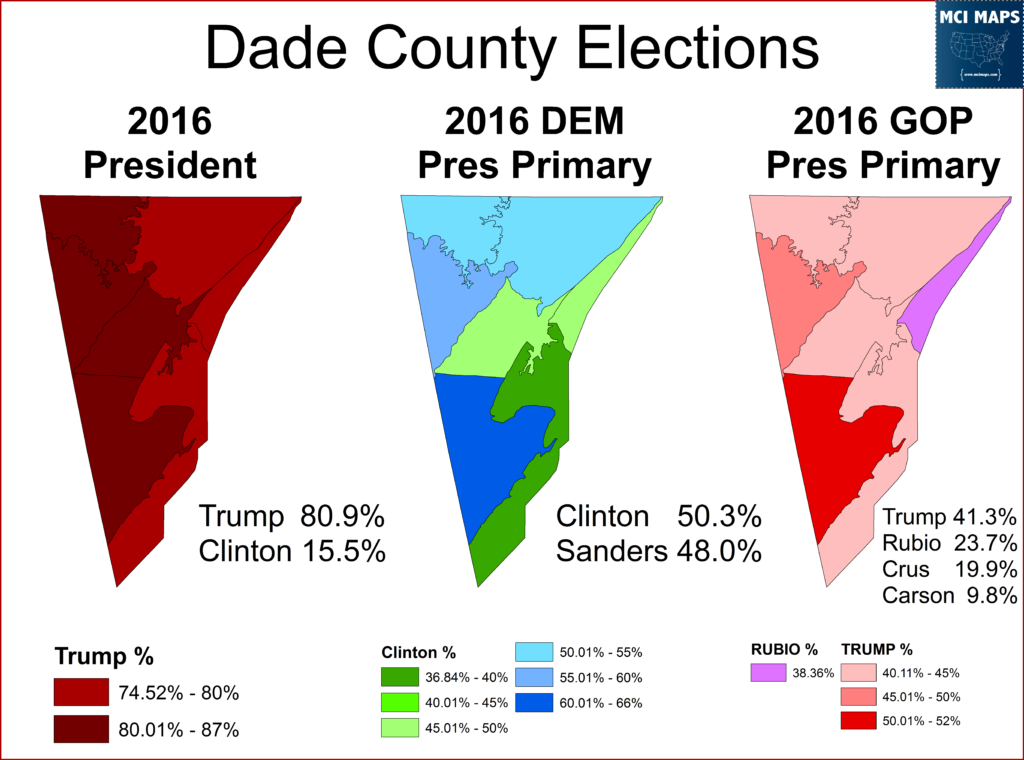

Water-wars aside, Dade’s role in the state’s political scene is minimal. The county doesn’t make up the largest vote share in its congressional, state senator, or state house districts. While Dade County used to be part of the solid Democratic south, it hasn’t voted for a Democrat for President since Jimmy Carter’s 1976 win. The county is now deep-red at the top of the ticket, giving Trump over 80% of the vote in the last election.

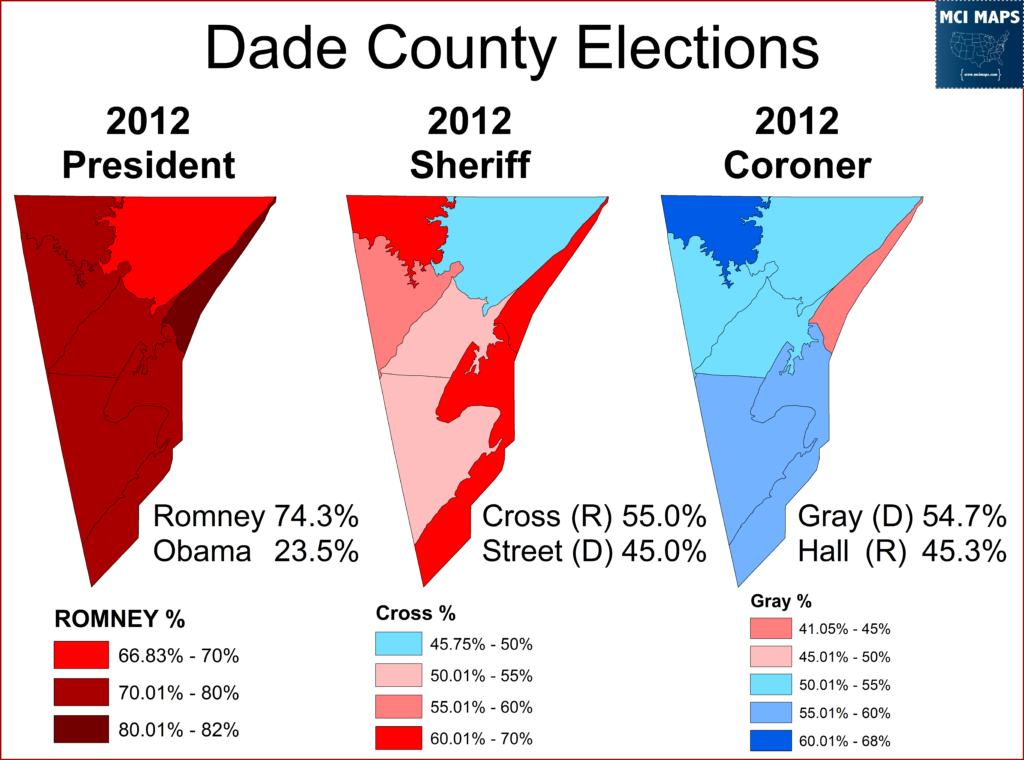

While the county is largely Republican, it does still maintain some ticket-splitting further down the ballot. In 2012 it gave Romney 74% of the vote while re-electing its Democratic Coroner and showing a competitive race for Sheriff.

The politics of Dade County put it firmly in the same camp as many former confederacy regions – former Democratic bastions that have turned solid GOP – but often with a local Democratic base. However, history shows that Dade County was not the rabid secessionist county.

The Secession Crisis

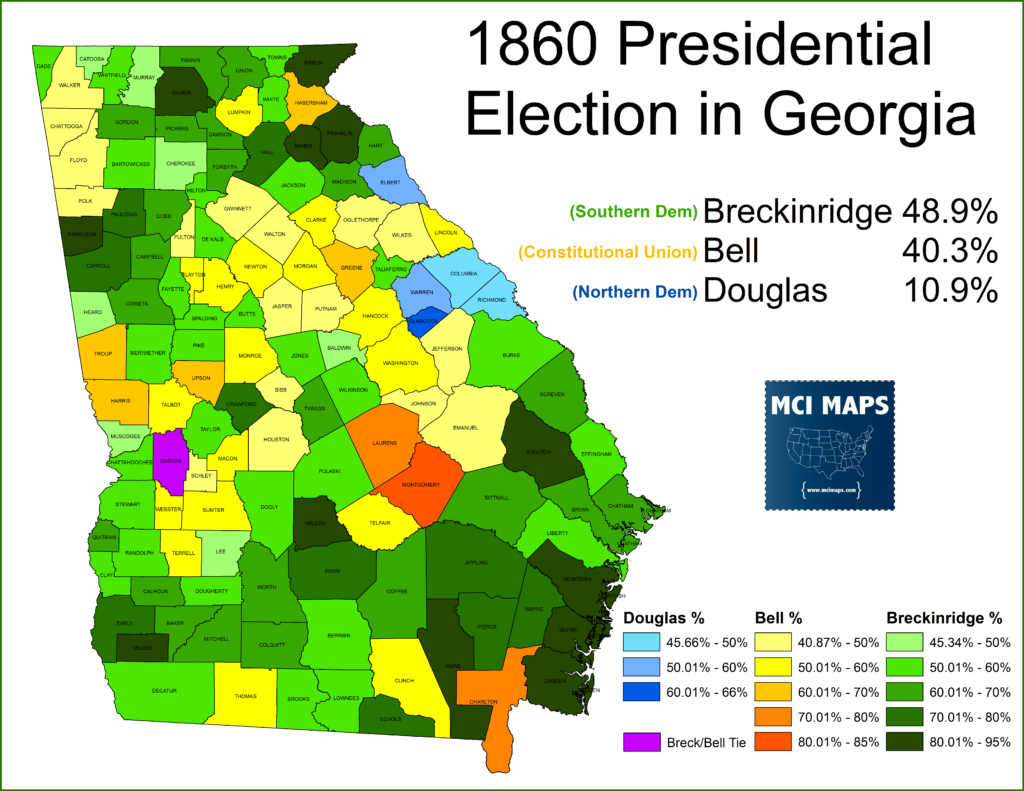

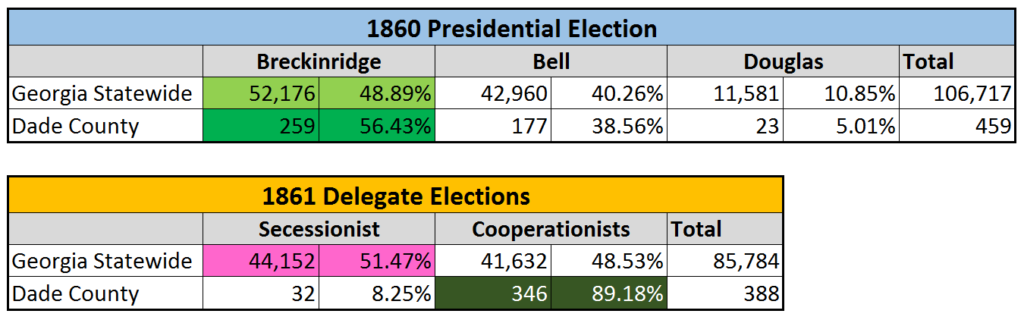

The way Dade County voted during the secession crisis is an important push-back against the legend of Dade leaving the union over slavery. Defenders of the legend point to Dade backing Breckinridge, the Southern Democratic candidate for President, in 1860. Breckinridge, who would go on to join the confederacy and argued during the campaign that states had the right to secede if they so chose. He won 49% of the vote in Georgia. Meanwhile, John Bell, head of the Constitutional Union Party; which favored finding any way to keep the union together, got 40%. Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas only managed 11% and Lincoln was not even on the ballot.

Breckinridge actually lost several of the prominent slave counties in the middle of the state while winning North Georgia, which held a very small slave population. Dade County gave Breckinridge 56% of the vote; higher than the state total but not close to the highest in the state.

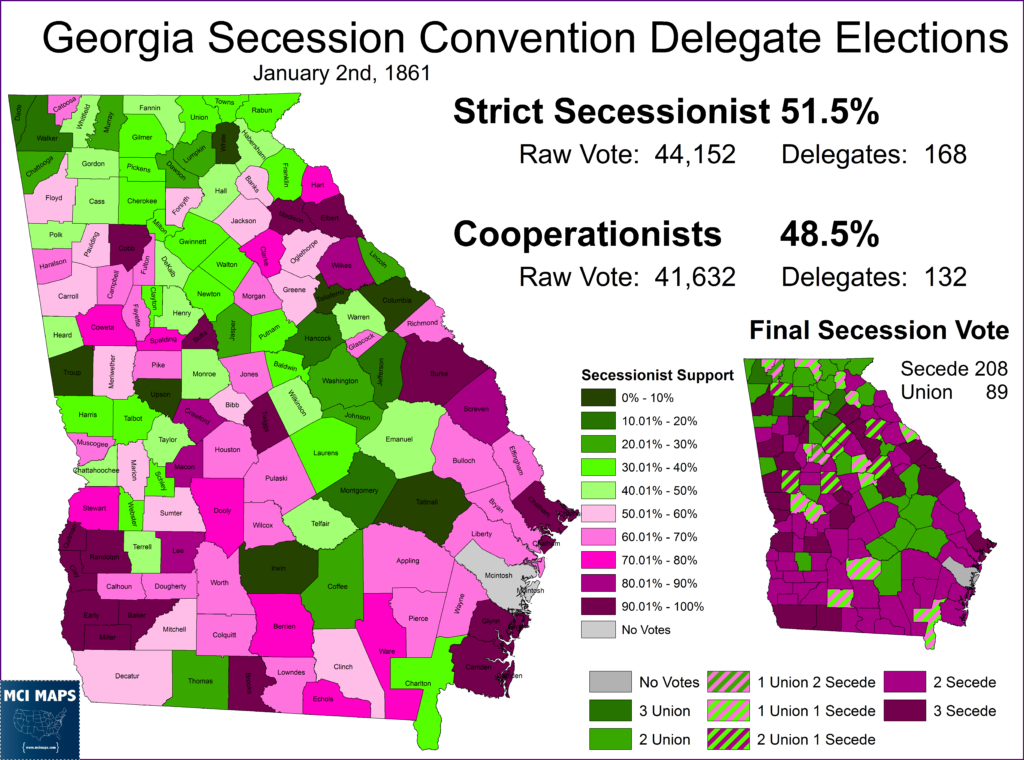

The election of Lincoln pushed Georgia toward secession. Like many of her neighboring states, Georgia held elections for delegates to a Secession Convention, which would decide the issue. The Governor of Georgia was a rabid secessionist and it took little effort to get the legislature to agree on the vote. Formal results are lost to history, but scholars where able to reconstruct the vote from newspapers and a report from the Governor released in 1861. The roll calls from the convention, which eventually voted to secede, are available as well.

The election results for delegates showed a very split state. Strict Secessionits (who favored immediate secession of Georgia) nearly tied with the Cooperationists (who were either unionists or those who wanted Georgia to only leave as a collective with other southern states).

There were a few key pockets of cooperationist and union support; the Pine Barren counties of middle/south Georgia and North Georgia. These counties voted heavily for cooperationist delegates and saw their delegations vote against secession when the final vote came. This included Dade County; which overwhelmingly voted to for a cooperationist delegation.

How Dade County performed compared to the state as a whole can be seen below. The county was more pro-Breckinridge, but so where several North Georgia counties that likewise sent unionist delegates to the convention.

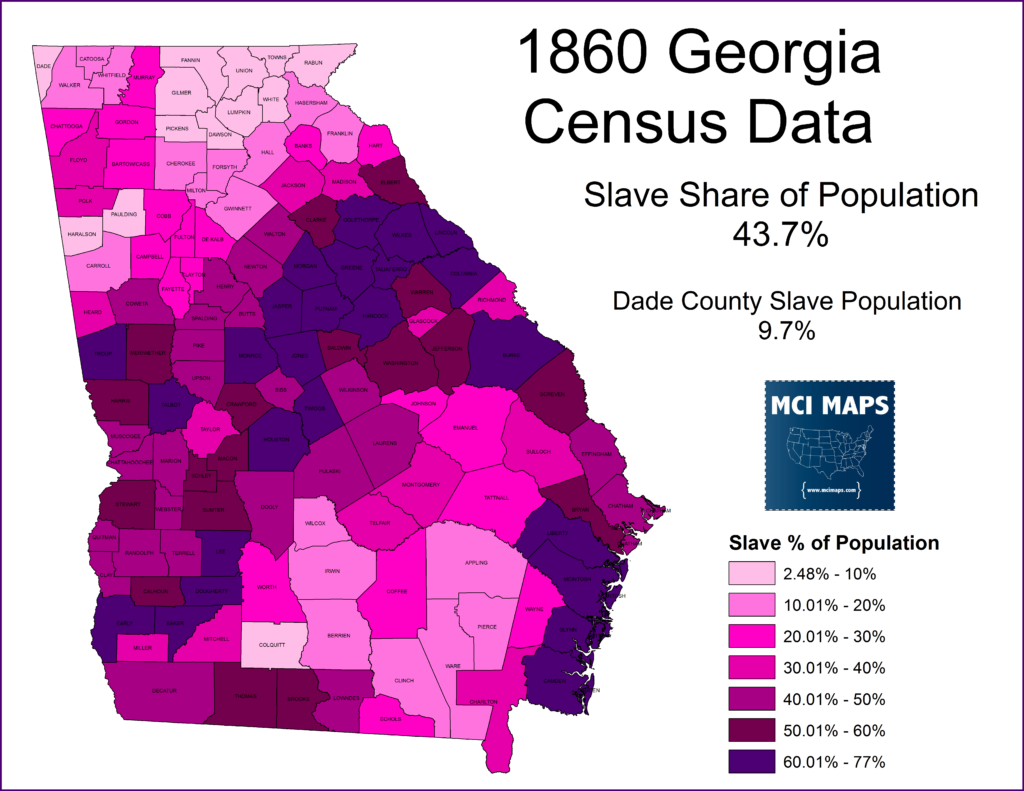

One of the reasons for North Georgia’s hesitance to secession stems from the lower slave population. The hills and terrain of the region make agriculture less fruitful and hence fewer slaves or plantations. In 1860, Dade county only had 300+ slaves, less than 10% of their total population. Georgia’s statewide population, meanwhile, was nearly 44%.

The narrative that Dade county was some rabid secessionist county with many slaves does not ring true.

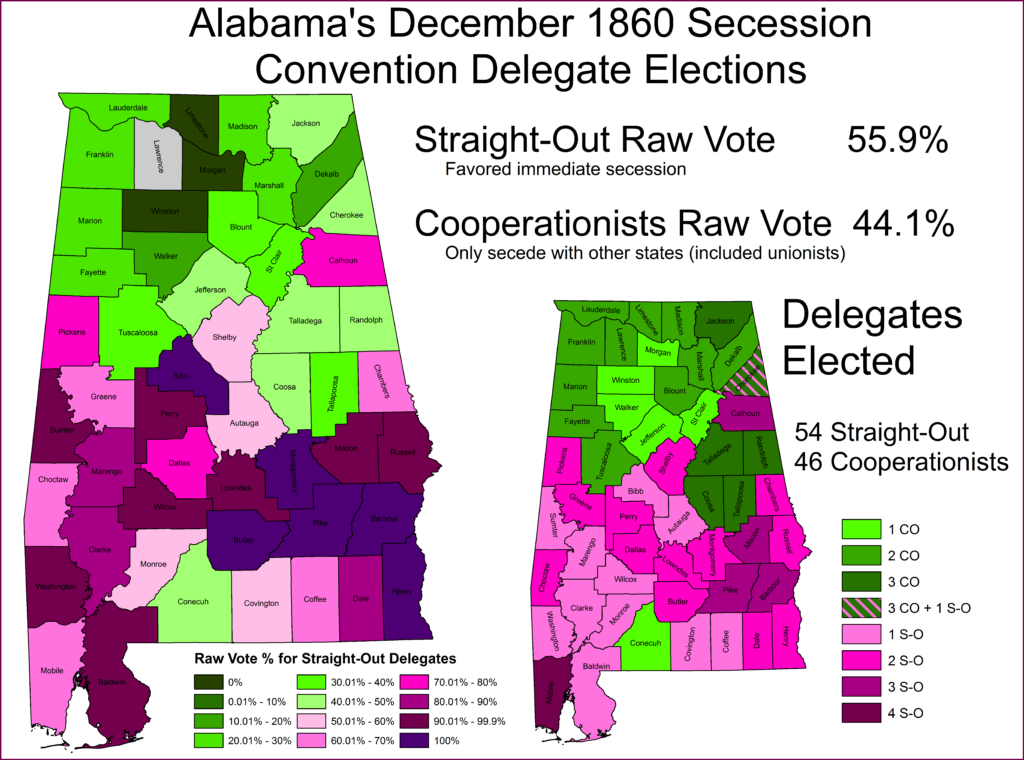

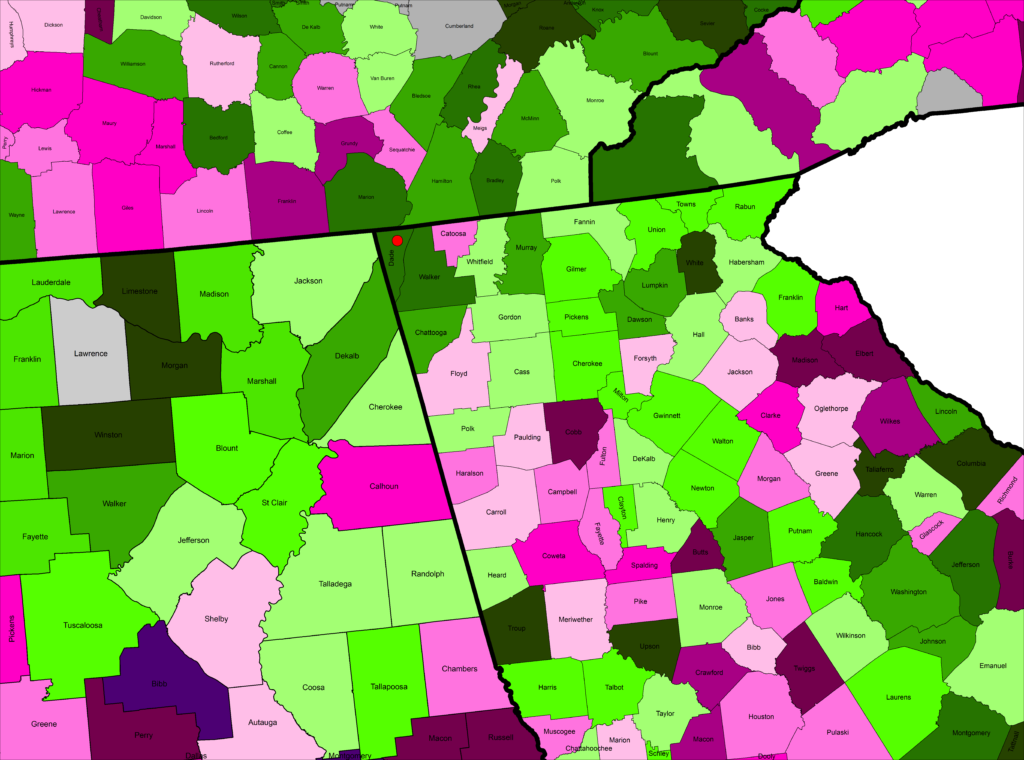

Dade’s hesitance on secession shouldn’t be too surprising given its location. The area of the nation it was in had lower slave populations and fewer plantations than more fertile land. Counties around Dade in other states where likewise hesitant to secede. Alabama’s delegate elections are below. Jackson and Dekalb Counties (Northeast Corner) share Dade’s border, and both voted for cooperationist delegates.

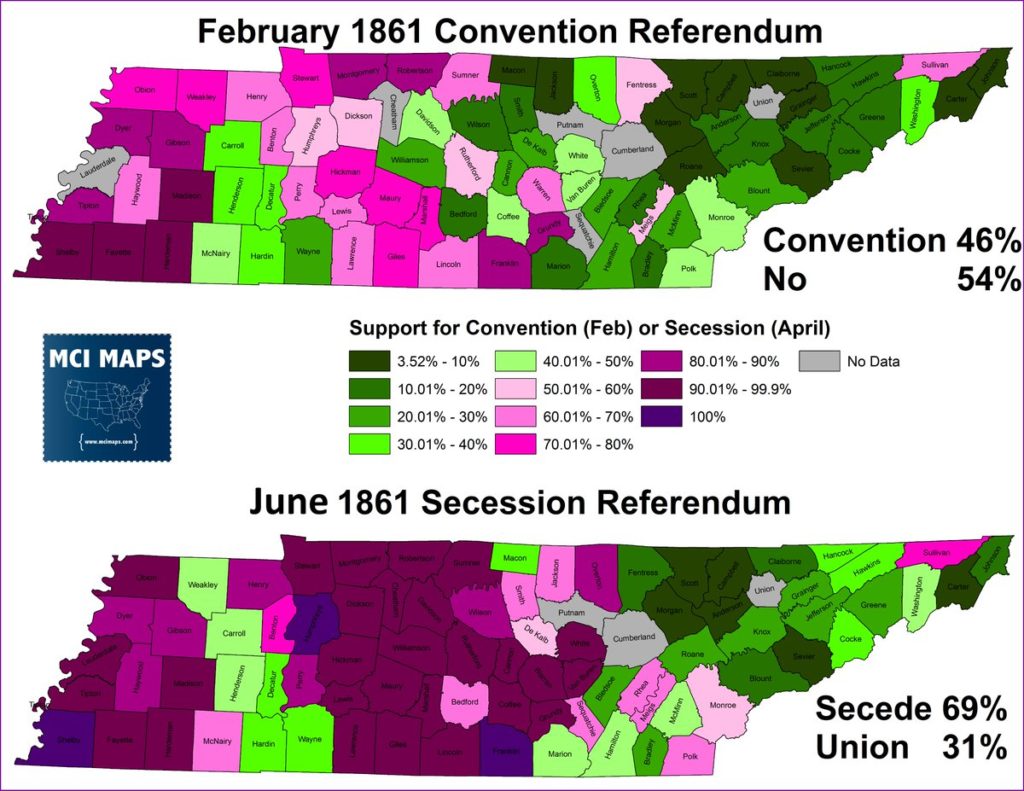

In Tennessee, the counties of Hamilton and Marion (southeastern counties) didn’t even support doing a convention in February and rejected secession in June; even after sentiment in the state had swung toward joining the confederacy.

Adding all the states together, plus North Carolina, and we see that Dade was in a region of the south that was much more cautious of secession than the states as whole.

It is impossible to believe that Dade may have left Georgia because the state was taking too long to secede. This narrative is counter to the politics of the county and its region at the time. So how did this legend rise up?

Dade’s Legend

Dade’s legend all hinges on State Representative Bob Tatum’s speech and gathering of the citizens of Dade County. However, there is nothing from the 1860 time period to corroborate the legend. The flaws of this “history” are well researched and detailed in E. Merton Coulter’s article in Georgia Historic Quarterly, “The Myth of Dade County’s Seceding From Georgia in 1860.” The key items the article points are as follows

- While “Uncle Bob” Tatum was a secessionist, he also favored a popular referendum

- No paper or House journal indicates and speech by Tatum was given

- Dade County didn’t send a resolution supportive of secession, something done by other counties

- Dade’s State Senator, R. H. Davis, was a strong cooperationist

- Tatum continued to serve in the then-Confederate Georgia legislature during the war, showing no separation from GA

- Dade sent a unionist delegation to the convention on secession

- A “glorying of the confederacy” sentiment that swept the South didn’t hit Dade till the 1890s

- The first mention of the legend doesn’t appear in papers until 1886, which claims Dade seceded from Georgia and the Confederacy

Coulter surmises that Dade’s legend is more due to its geographic isolation than anything else. The legend was a joke and story told via the residents but rarely printed or regarded as serious. Indeed Dade County was very isolated from the rest of Georgia. A mountain range divided the county from its Georgia neighbors and no roads connected Dade to its neighbor, Walker county. Folks in Dade would have to drive into Alabama or Tennessee to then enter Walker County. This road map from 1936 shows the lack of a connector road.

Dade wouldn’t be connected to Walker until 1941, when Highway 136 was built.

So it seems the “State of Dade” was a bit of a local legend meant to lampoon the county’s isolated status in Georgia. This could be seen similar to Key West “seceding” from American and becoming the “Conch Republic.” Of course Key West’s action was a much more visible publicity stunt, while the “State of Dade” seems more like an internal joke that grew into a greater legend. By all accounts the tales of the Speech by Bob Tatum and the issue being over slavery seem to have been added to the legend later on. Instead of the origin simply being “they are isolated by mountains” it became “they were super pro-slavery.”

The isolation fits, considering the ceremony of Dade “rejoining the union” was in 1945, just a few short years after the road was built. The celebration also takes place at a time in World War II shortly after Germany surrendered and Japan seemed sure to fall. The celebration served as a good feel-good moment and symbol of unity. President Truman even sent a message saying “Welcome home, Pilgrims” on the big day.

The legend of Dade was further commemorated during the US Mint’s state quarter project when the Georgia design had a notable chip in the state’s northwest corner.

It has never been made clear if the chip was intentional or not. The Mint claims it was an accident, however, the lack of any future correction indicates to this writer that the design was indeed meant to honor the legend of the “State of Dade.”