Note to readers: This post is going to be very different from previous articles. Rather than discussing a normal election or demographic trend, I will be looking at Florida’s 2013 election for Democratic Party Chair. This post will cover a bit of history of the race but focus largely on the weighting system used to elect the leadership and if change are needed. Enjoy!

Eight months ago, the Florida Democratic Party was in the midst of a heated leadership battle for Chair. Democrats were coming off major successes in 2012: gaining four US House seats, several state legislative seats, re-electing Bill Nelson, and delivering the state to Barack Obama for a second time. Chairman Rod Smith opted not to run for a second term as chair, and after the dust was settled two candidates emerged: Allison Tant of Leon County and Alan Clendenin of Hillsborough County.

Allison Tant was a prominent Democratic fundraiser for President Obama during the 2012 election cycle. Known in political circles as a “bundler” (a big dollar fundraiser), Tant delivered over six-figures to the President’s re-election campaign from the Tallahassee metro area. With fundraising being a prominent task for any Party Chair, Tant certainly had the right pedigree for the job. She announced her candidacy shortly after the November elections and was elected Chairwoman of the Leon County Democratic Party in December.

Alan Clendenin was a state committeeman out of Hillsborough county. He had planned to run Chair in 2010 but opted against when Rod Smith entered the race. He laid the groundwork for his 2012/2013 campaign early and his campaign had the theme of building up the state’s grassroots efforts.

Tant had the backing of DNC Chair Debbie Wasserman Shultz and Senator Bill Nelson. Such establishment backing made Tant the favorite to win the election in January.

Around late December and early January the papers and political blogs began to publish stories that insinuated Clendenin was catching up to Tant in the battle for chair. They ran stories claiming a loss for Tant would be black eye for Bill Nelson and Wasserman-Shultz. These articles, however, were incorrect. Tant always maintained a lead in the vote count behind the scenes. Papers and the Clendenin campaign relied on soft endorsements and assumptions that would never actually swing in their favor. The truth was Tant always led in the vote.

It was true that Clendenin had a large block of votes in his camp. However, Clendenin’s base of support did not come from a mass of committeepeople pledging to vote for him. The bulk of Clendenin’s support laid in one factor: the weighted vote.

How Florida Democrats Elect their Leaders

The Florida Democratic Party has a weighting system in place for its leadership elections. Each county has two people casting ballots, its Committeeman and Committeewoman; who are elected by their local county party. However, a committeeperson’s vote is worth more or less based off a formula the Party uses to determine the influence each counties delegation has. Party registration and Democratic candidate performance are all factored. Each committeeperson is guaranteed their vote will count, so the minimum any county will get is 2 votes. However, the formula results in Miami-Dade getting 118 votes. This means a committeeperson from Miami-Dade has a ballot worth 59 votes (59 for the committeeman and 59 for the committeewoman) while the committeeperson from Lafayette has a ballot worth 1. If a local county party did not organize and elect committeepeople, then that county would not have a say in the election.

The formula works as follows for each county

- Take the county’s registered Democrats and divide it by the states registered Democrats. Multiply the results by 100. This indicates the percent of statewide registered Democrats that each county accounts for. We will call that figure D

- Take the county’s Democratic share of the vote for the last time it voted for President, Senate, Governor and divide each by the statewide totals for the respective race. Add the three fractions together and divide them by 3 (to get the average). This indicates the average percent of democratic candidate votes that the county in question provides for the statewide total. We will call this figure C

- Add figure C and D together

- Multiply the answer by 5

- Round the total to the nearest even number (up or down).

- Any county that would round to 0 automatically gets 2

This is the method for allocating weighted votes to each county.

These county votes for the 2013 election totaled 1020. In addition, elected Democrats across the state were also given votes to be cast weighted based on the nature of the office. The vote of the elected officials totaled around 168, bringing the total 1188 potential votes in the chair’s race.

This article will not focus on the elected officials and how they vote. Their ballots do not account for more than 10% of the total votes cast. The main focus here is on the weighted system being used for the county votes; that is where a problem lies.

The Problem with the Current System

Clendenin was always an underdog to win the Chair’s race despite what his camp and the papers believed. The weighting system allowed him to amass a large block of votes, but that was not because he was racking up the large numbers of individual endorsements. The reason Clendenin was able to get a large chunk of votes was him locking up support from big counties, especially Southeast FL. Clendenin secured the backing of the committeewomen of Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach; as well as the backing of the committeemen of Miami-Dade and Broward. Those ballots alone equaled 275 votes. In addition, Clendenin had firm control over his base of Hillsborough County, which gave him another 66 votes. Hillsborough was always going to go his way because he maintained a strong control over the county (not to mention he was the committeeman). Tant, meanwhile, came from Leon, which only had a third of Hillsborough’s votes.

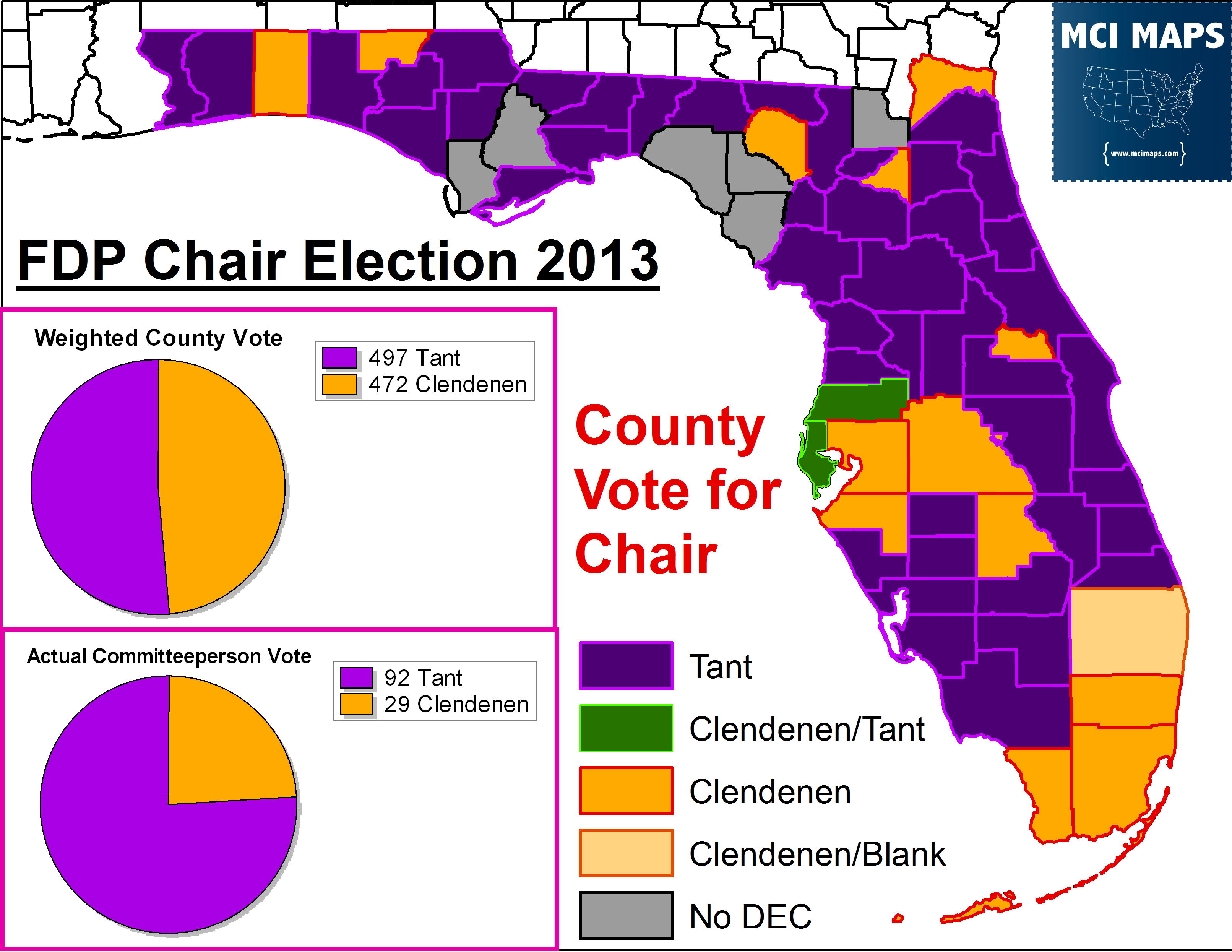

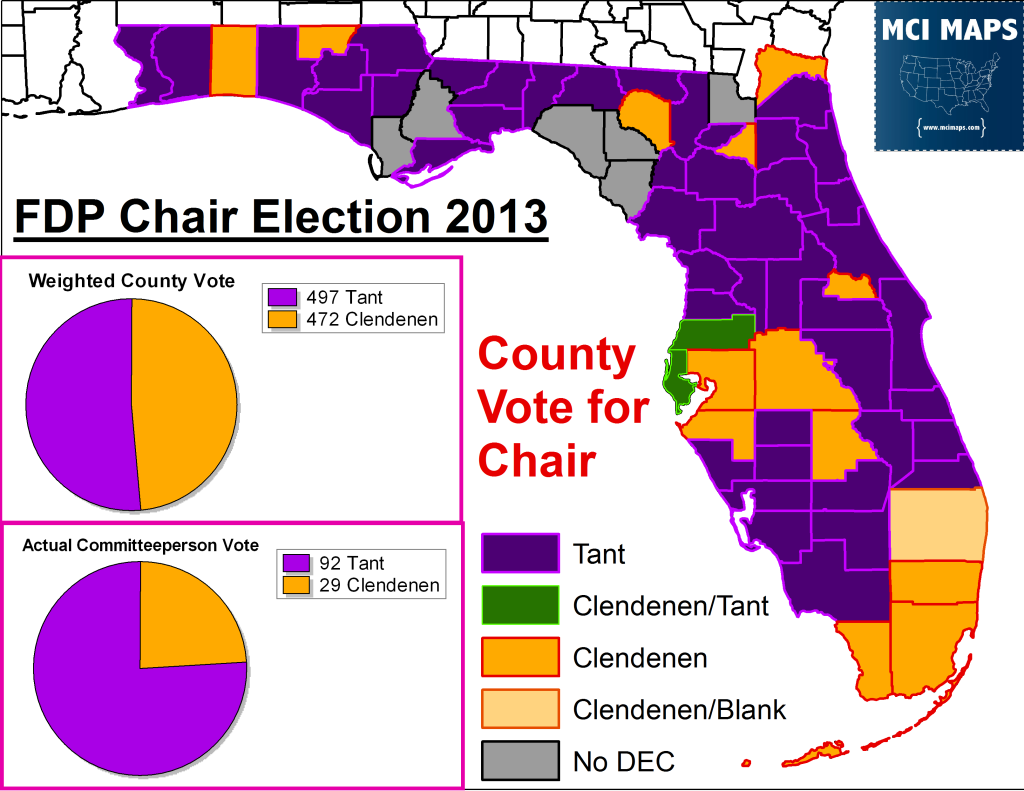

Those counties along along with a handful of smaller counties allowed Clendenin to claim enough votes to appear competitive to the papers. Indeed Clendenin was able to come close in the county-level vote thanks to the weighting system. Look at the map below of the results of the race. Allison won a narrow victory in the county-vote category and walked away with most of the elected official votes (which is not reflected on the image). Note the two pie charts which show how Tant and Clendenin did based on the weighting of the vote AS WELL as the vote among the actual committeepeople casting those weighted ballots.

Tant secured the support of over 75% of the committeepeople casting ballots, but thanks to the weighted vote she barely edged a majority of the county vote.

How the counties voted and the totals were derived from several sources. The balloting results were not published online or by the party, so bare with me if any errors occurred. Please inform me if any errors are noticed.

Note that six counties did not organize local county parties to send representatives to the election, so they had no vote. In addition, Palm Beach county had its committeewoman vote for Clendenin but the committeeman (who had pledged support for Tant) saw his ballot rejected due to no signature.

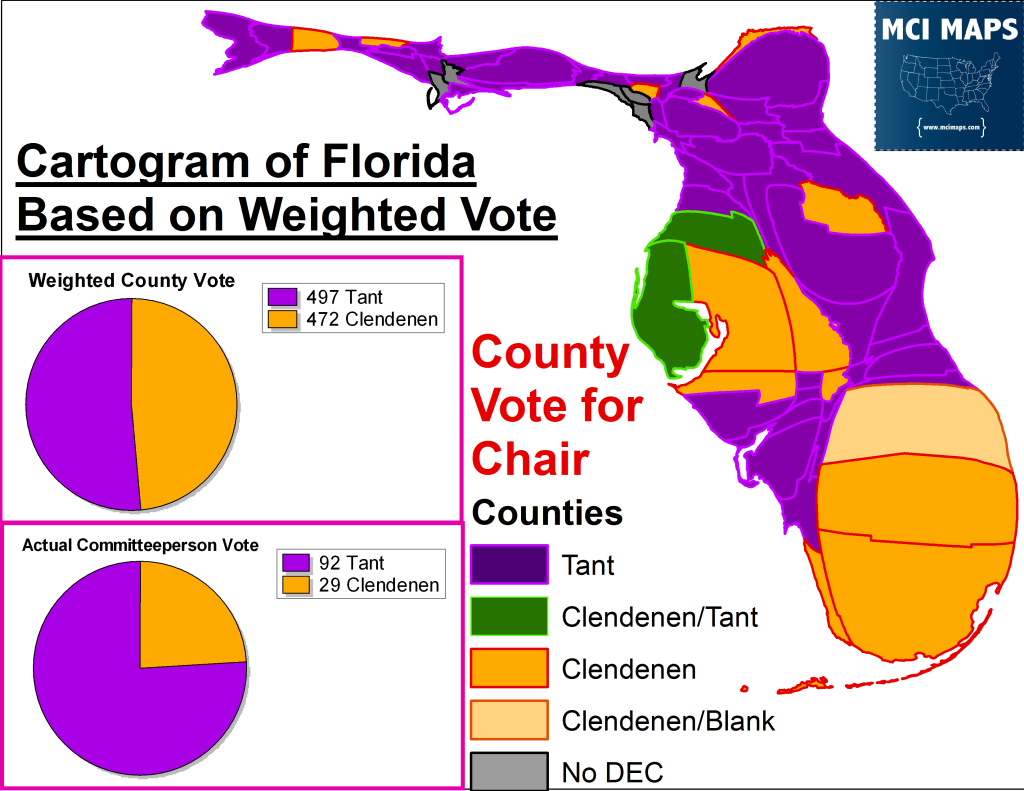

How could less than 25% of the committeepeople nearly overtake the majority of the weighted vote? Look to this cartogram of the counties by their weighted vote. The county boundaries are manipulated to confirm with the weight each possesses.

There certainly is something to be said for weighting votes to account for registration and/or Democratic performance. In fact, the current weighting system does a good job of representing the influence a county has on an election. The percent of the weighted vote a county contains under the current system mirrors the percent a county contributes to the statewide Democratic totals within a 1% difference.

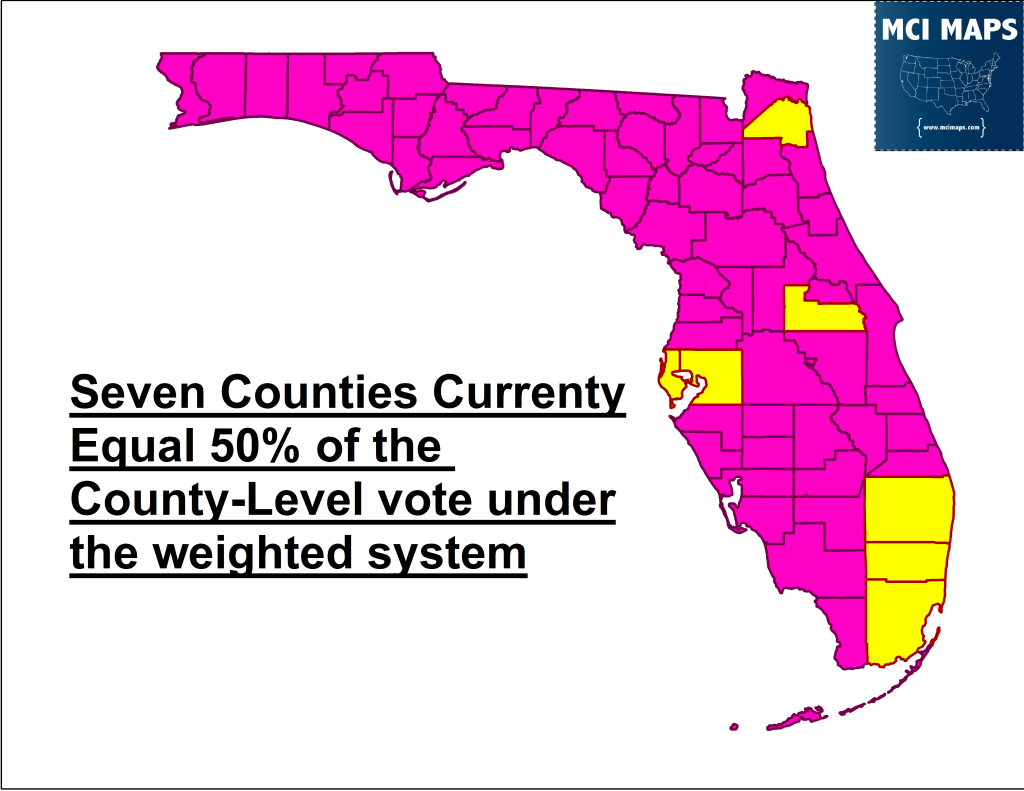

However, the current system skews heavily in favor of the major urban counties. Under the current system, seven counties total half of the county-level vote. If the committeepeople of the largest seven counties got together and agreed on a slate of candidates for leadership positions, they could dominate the county-level vote even if every other county united against them.

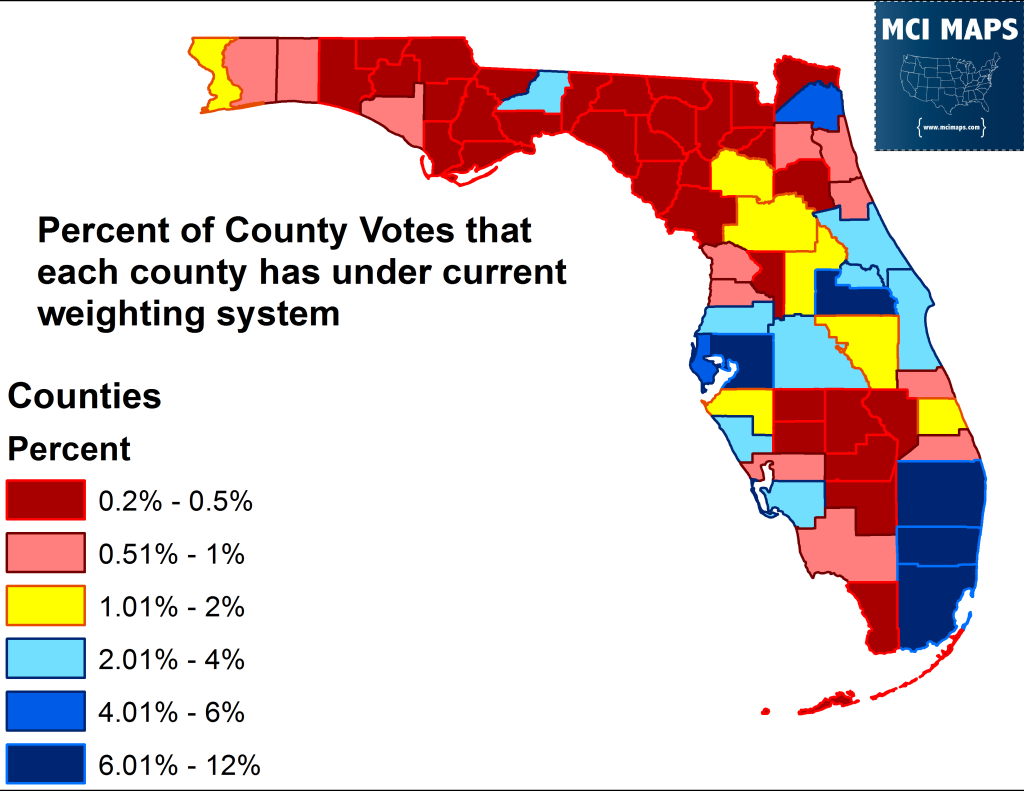

The current weighted system gives an enormous amount of power to large counties. Rural counties and medium counties are overlooked in the voting process because their support carries so little weight. The map below shows the percent of the county-level vote that each county gets under the current system.

A grand total of 33 counties, HALF of the total, fall under half a percent of the vote. In total these 33 counties account for 7.65% of the vote cast. Meanwhile Miami-Dade is 11.57% alone. 30 of those 33 counties are officially defined as rural by the State of Florida — possessing less than one hundred people per square mile. The other three, Sumpter, Nassau, and Putnam, were qualified as rural until 2010; but for the purposes of this article I am including those counties and the other 30 when I mention ‘rural’ counties.

At this time it is worth reminding everyone that Broward’s 116 votes or Miami-Dade’s 118 votes are each split between just two people. The counties are not being awarded weighted votes that allow them to bring x number of people to the central committee, instead a handful of individuals are given immense power and influence because they reside in counties with large populations. Make no mistake, performance does factor into the weighting system, but it is impossible for a small county that gives Obama a large percent of the vote (like Gadsden) to come close to an Obama county that has a large population (like Palm Beach). The largest counties can easily control who is elected Chair or elected as members of the Democratic National Committee.

In fact, while the large counties split on the chair’s race (the support of Duval and Orange for Tant was key), the large counties were able to control which five men and five women would be selected to the Democratic National Committee. Most of the largest counties united to select people to the Democratic National Committee that resided in the largest counties or were aligned with them. In the end, 6 of 10 were selected from the top seven counties while two came from Leon, one from Seminole (which voted for Clendenin), and one from Volusia. All counties in question have big or medium populations. In addition, the race for Secretary saw a Tant-supporting incumbent, Rick Boylan, of Pinellas, lose his re-election when the large counties united against him. Boylan would be able to bounce back with a DNC spot thanks to help from some smaller counties and a good deal of sympathy for his ouster. This is not a knock on those selected but rather serves to highlight that those who fight in the small counties or medium counties have a limited chance of getting elected to any position. The only small county committeeperson elected to a statewide leadership position was Judy Mount of Jackson County; who was unopposed.

Movements to reform the system have been in the works for years now. The 2012 Presidential caucus system was developed to comply with new party rules. However, a side effect was it helped helped shift power away from the large counties. The caucuses were the method Florida Democrats chose for the selection of delegates to the National Convention. People got to run in their home counties for slots to go to the statewide Democratic convention. These elected delegates went to the statewide convention and competed with fellow delegates who came from counties in their congressional districts to determine who would represent that district at the National Convention — each district got allotted eight people. This allowed average voters and Democratic activists to take part in the system and was a far cry from 2008 when the large county committeepeople got to exercise a great deal of influence on who was elected to represent the congressional districts.

These reform movements keep growing as new proposals for the weighted vote gain steam.

Proposed Reforms

Two key reforms have been discussed to alleviate the concerns that too much power rests in a handful of committeepeople.

Reform 1: Split up the vote

One proposed reform is to allocate one person for each weighted vote. Rather than the Broward committeepeople getting 116 votes divided between two people, it would be divided between 116. Such a system would reduce the ability of a small group of individuals to control the election (although not entirely). However, tactically speaking, putting over 1000 people in a room is not reasonable. One potential compromise would be setting a maximum weight that one person’s vote can be worth. For example, if a person’s maximum weight was 10 votes, then Broward would need to send 12 people to get all of its 116 accounted for. Such a system would allow internal dissent in the counties, with some members supporting one candidate even if most of their colleagues supported another. Only a few counties split their votes in 2013. There would likely be a greater deal of county splits under this proposal.

A similar idea would be to have counties divided into multiple jurisdictions based on certain population figures. For example, Miami-Dade could be split into a jurisdiction for every 100,000, or 10,000, or 60,000 voters, with each jurisdiction electing a set of committeepeople. Larger counties would have more divisions and thus more committeepeople to send to the central committee. The criteria for divisions could be many things: registered Democrats, total votes for President, or simply registered voters. The system is similar to how several county DECs divide themselves into county commission districts and elect district leaders.

Reform 2: Equal Proportion in Elections

Another proposed reform by individuals has been to give equal weight to all the counties — two votes each. This proposal is based on the notion that each county matters as the Democratic Party works to expand its base. There are two major problems with this proposal. First, and most important, the system is not allowed under Democratic Party rules. Second, this proposal does nothing to factor in large population bases or counties that perform more Democratic than others. In addition, the proposal is too reminiscent of the Pork Chop Gang of Florida’s past. The state used to be ruled by rural legislators who had malapportioned the state senate to ensure only one seat per county. The result was a state senate where 15% of the population ruled the state for decades. The result was a Supreme Court ruling that demanded reapportionment. This proposal, in addition to going against party rules, is too extreme for consideration. This proposal is dead on arrival, but I felt it was important to address.

A Potential Compromise

The current weighting system has two key problems: too much power in a handful of individuals, and the smaller counties have too little say. Right now the rural counties (which accounts for the 33 counties previously discusses), are overpowered by Miami-Dade or Broward alone. The solution of appointing more people to a county doesn’t solve the proportion issue and the equal vote premise is too far in the other direction.

There is, however, a proposal that can meet the two conflict sides halfway.

- Each county gets two votes, one for each committeeperson

- An additional vote is allocated for each of the 120 state house seat

There are several methods that the representative for each district could be selected. Party leadership could have input, the Democratic state reps could be the choice, or the local parties could select a candidate. One vision is similar to the 2012 caucuses. Under this proposal the DEC members would cast ballots for the district they reside in — similar to how they elect their county division representatives. If a district crosses county boundaries, the total votes for candidates would be added from all the participating counties with the winner being selected.

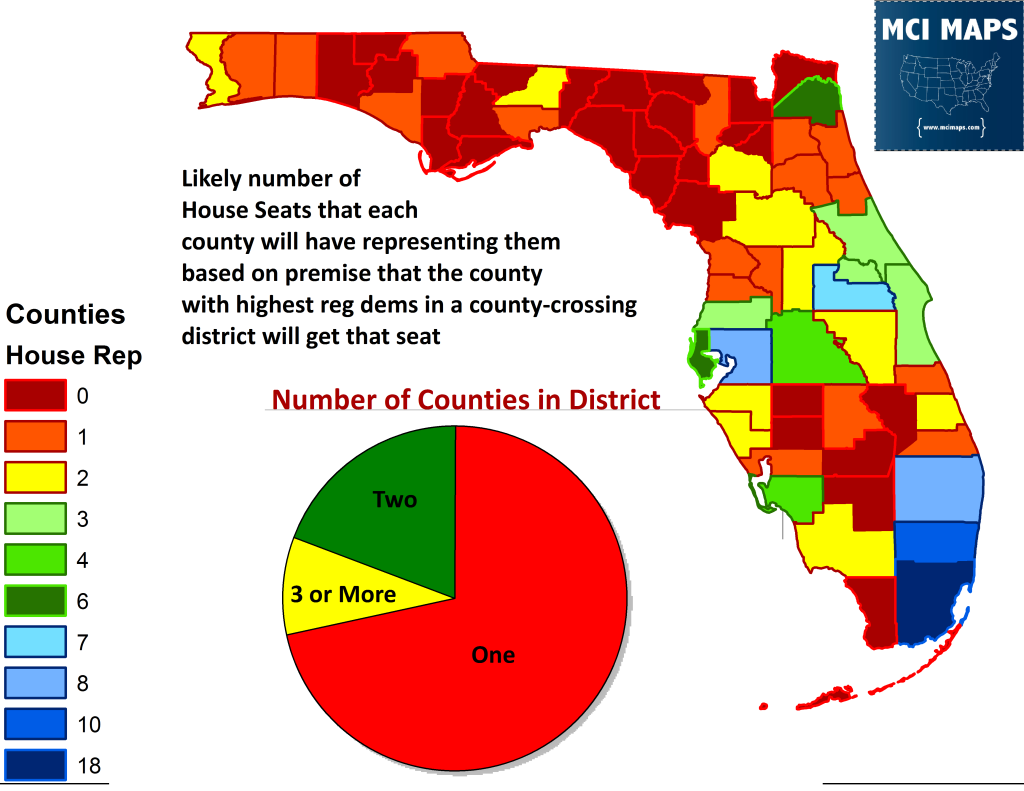

For the purposes of this experiment, I determined that the county that would end up getting the state representative slot would be the one with the most registered Democrats residing within that districts borders. For example: House District Seven crosses several counties, but Wakulla has the most registered Democrats within it; so Wakulla would likely win the slot. Both Madison and Taylor counties, however, would have a shot at winning the slot.

This proposal allows rural counties to get extra seats and rewards counties that organize strong DEC’s that can unite around a candidate for the state representative seat. The bigger counties that hold several districts will be guaranteed the most weight and by splitting the counties up it will ensure their is less centralized control. Such a scenario could easily see counties cast split votes in Chair and DNC elections.

86 house districts are entirely within one county, another 23 comprise of two counties, and the final 11 have three or more counties within or crossing their boarders. Using the “largest number of Democrats” criteria, the allocation of additional votes to each county would break down as seen below. Each county starts off with two votes, so adding the number of house districts it will likely receive gives the new weighted vote for that county. The total county-level vote is reduced from 1020 to 254.

Several counties are still unlikely to receive any extra votes, however, they have a fighting chance under the new system. These allocations could change depending on how hard counties make plays for the seats crossing their boundaries. For example: Miami-Dade dominates 18 districts but splits three with Broward county that could easily go for Broward with enough organizing.

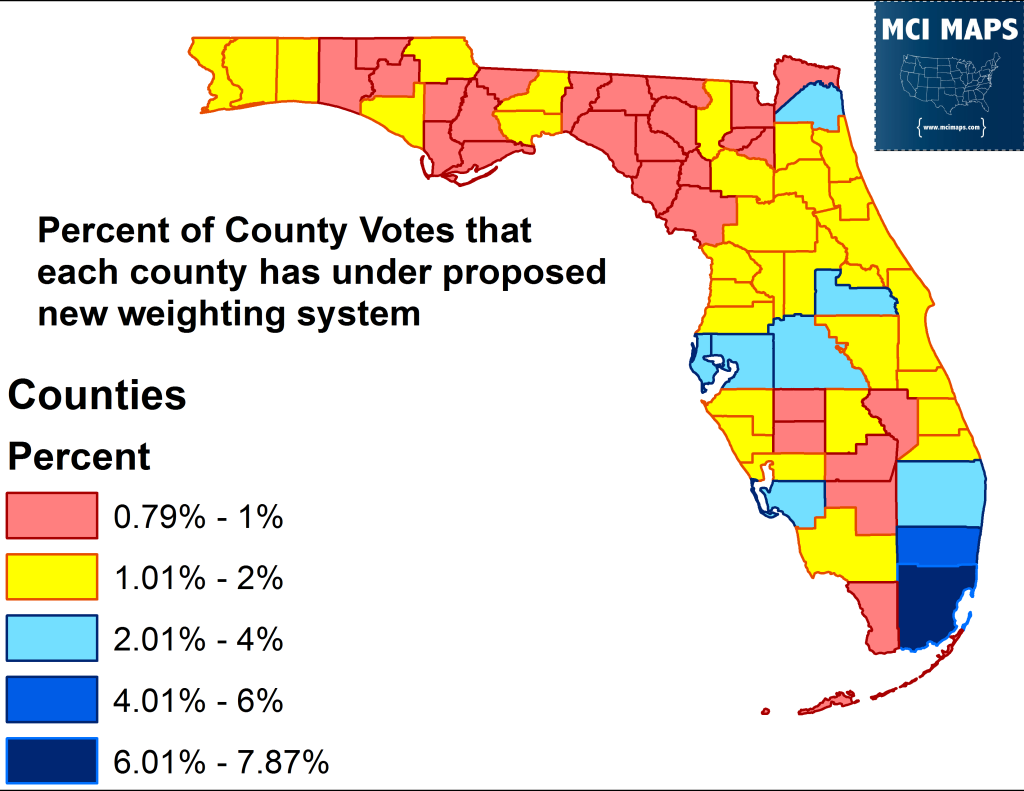

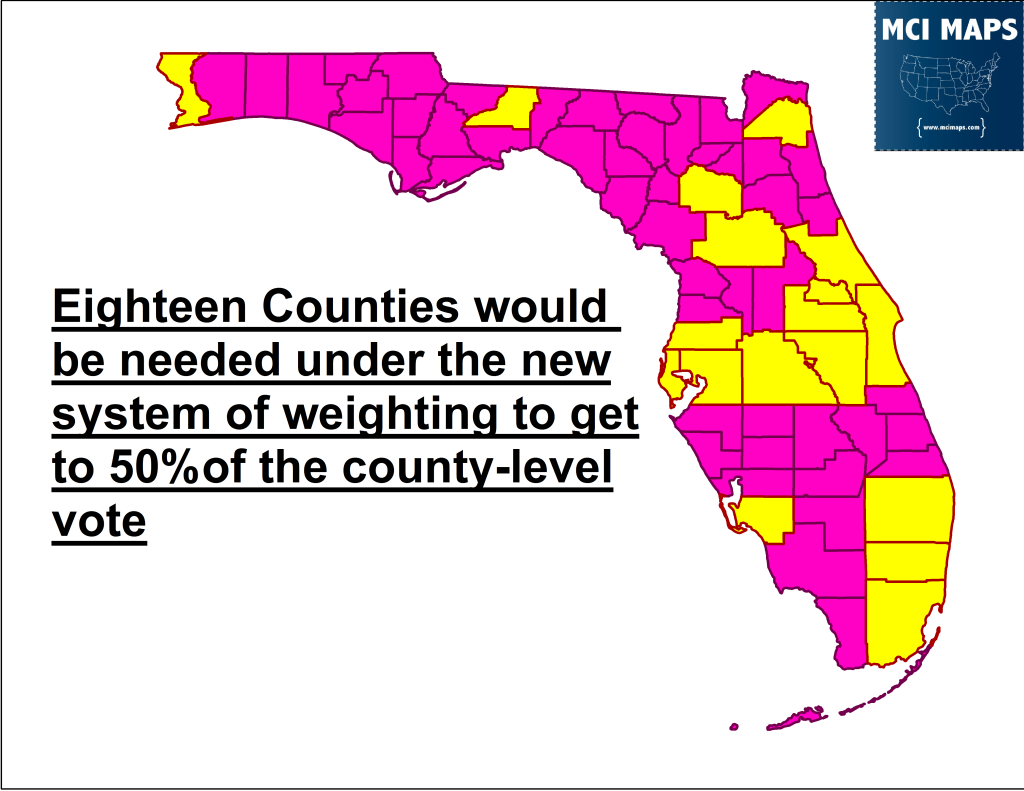

This system of weight allocation limits the overarching influence the largest counties have on the process. Smaller counties have the opportunity to gain additional seats while the largest counties max out at 20 total votes or less. The result is the larger counties losing some of their influence while rural counties gain influence. Below is a map of the percent each county posses in the county-level vote under the new plan.

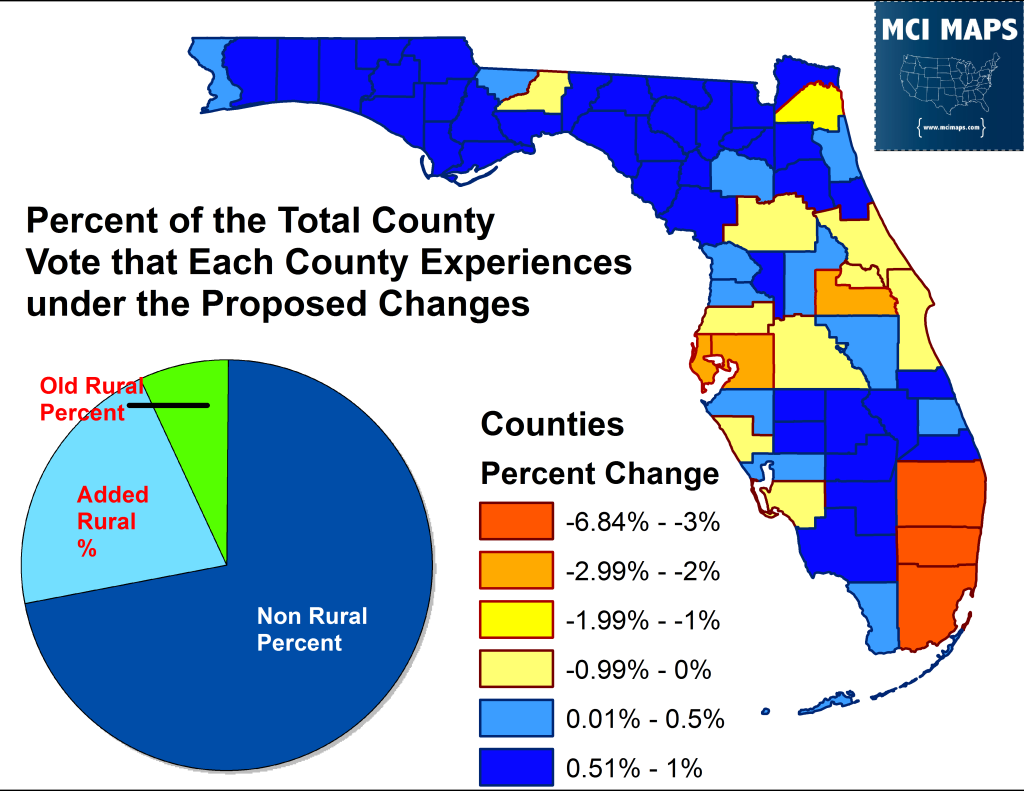

Compare this map with the former one of county percent under the current weighting system. Notice that no counties fall under the 0.5% mark versus 33 from before. Those same counties see their totals jump from 7.6% to 28%. The image below shows the changes each county experiences in terms of the total weight it held. The southeast loses the most, but no county loses more than 7% while several rural counties gain around 1% each.

This new allocation allows the 33 rural counties to form a block that has some influence but still gives medium and large counties the say if they unite. Most important, it now takes many more counties to unite together to control 50% of the weighted vote. Under the current system, 7 county delegations could unite, under the new plan it would take 18.

This proposal is just an idea, but it shows that a compromise can be reached between the groups that want equal votes and those who are hesitant to change the current system.

Final Thoughts

Right now the current weighting system for the Florida Democratic Party creates an environment where fourteen people can control the agenda if they unite together. Such a system is too vulnerable to corruption and compromise. Reforms are needed to create a fairer playing field for small and medium counties. The least that must be done is to take the power out of so few individuals hands. Make no mistake, as a native of Broward County I am working against my home’s own interest in supporting changes to the system. However, this is about what is best for the party as a whole. The system needs to be changed sooner rather than later.