As we approach the end of black history month, and with redistricting still ongoing in Florida, I have decided to take a look at the career of Al Lawson. Born in Gadsden County, Lawson is a trailblazer in the panhandle of Florida. His elections to the legislature made him the first black elected official in the region for many offices for the first time since reconstruction.

Lawson grew up going to segregated schools in North Florida. In the summer he worked in the tobacco fields. The 7-foot-tall Lawson secured a basketball scholarship to go to Florida A&M University, a Historic Black College in Southside Tallahassee. Lawson would become the first black assistant coach for FSU basketball and served as a Florida A&M booster through the 1970s. He became an insurance agent, and was a well-known and respected businessman when his electoral career began. Let us take a look at that career.

The Florida State House

Al Lawson’s electoral career would begin in the 1980s. It came as a result of the 1982 redistricting process in Florida. Florida’s 1981-1982 redistricting process, which I covered in detail in this article, was a major shift for representation in Florida. Facing the risk of lawsuits, lawmakers agreed to end the use of multi-member districts and use entirely single-member seats for the legislature. This was designed to give minority voters greater representation. The move would result in that increased representation, but many regions saw questionable lines. The Florida panhandle was one such area.

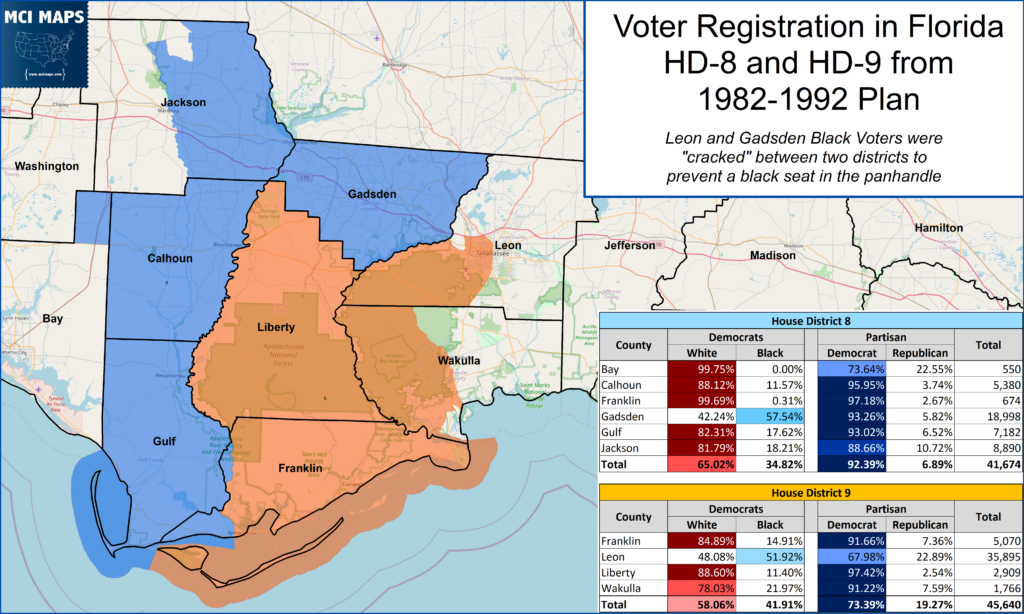

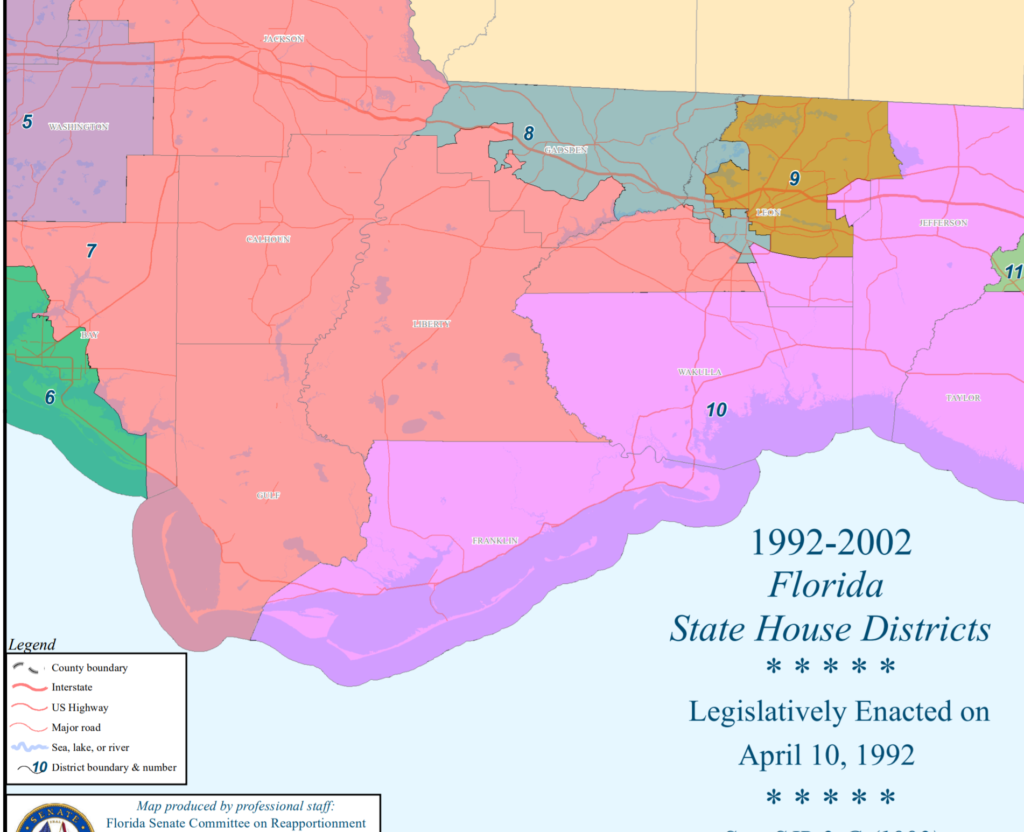

Heading into redistricting, African-Americans argued that a state house district that connected Gadsden County and southwest Leon County should be drawn. Gadsden is Florida’s lone majority-Black county, while southside Leon County has a large black population. Such a district would be majority black and guarantee black representation in the panhandle. Instead of drawing this, lawmakers crafted the districts seen below.

The map created made both HD9 and HD8 black-access seats, but were carefully drawn to give white voters the advantage in both. Lawmakers would argue they were giving black voters influence in two seats rather than packing them into one. Issues around packing or cracking a minority community can be tricky; especially when determining motive. However, the broad agreement in this case is white lawmakers defied the wishes of local black leaders; opting to divide the black community.

HD8, which included Gadsden, would be represented by a white democrat for its entire tenure. HD9, meanwhile, would would be the site of Lawson’s first campaign. Despite the questionable lines, black voters in Leon, who were fighting for representation in local government, would make HD9’s 1982 race a top priority.

1982 Election

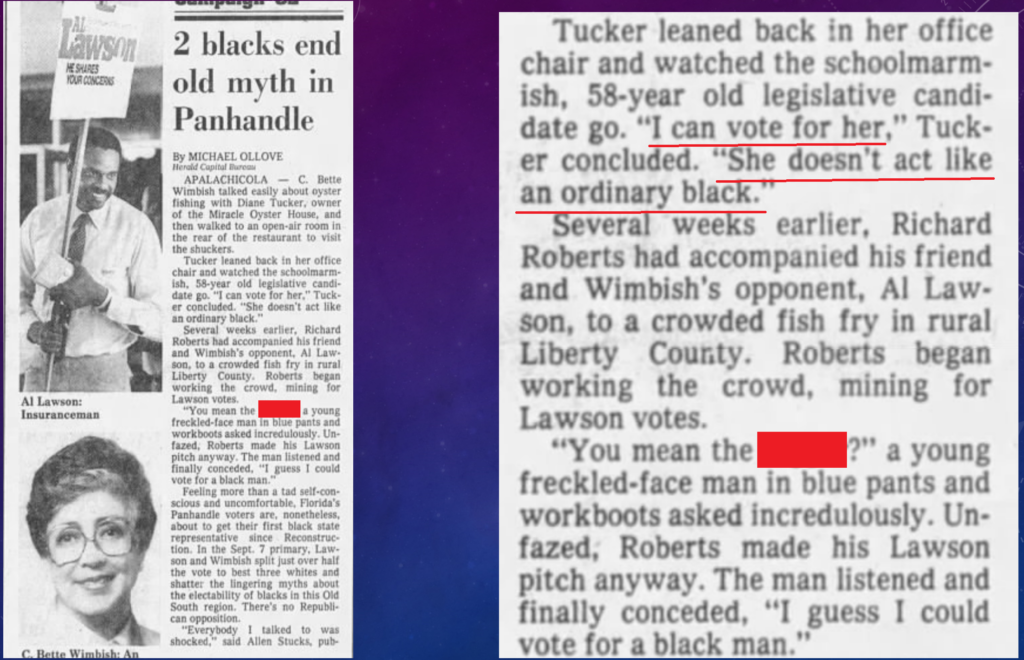

House District 9 was designed to elect a white Democrat. The seat was clever in how it paired the black community of Leon county with rural, white Democrats in the outstanding counties. Today, the counties of Liberty, Wakulla, and Franklin, are solidly Republican. Back then, these were democratic communities – albeit rural Democrats with a GREAT deal of racism and racially polarized voting. White voters in suburban Tallahassee, meanwhile, were less polarized, though still not nearly as racially-blind as they are arguably today.

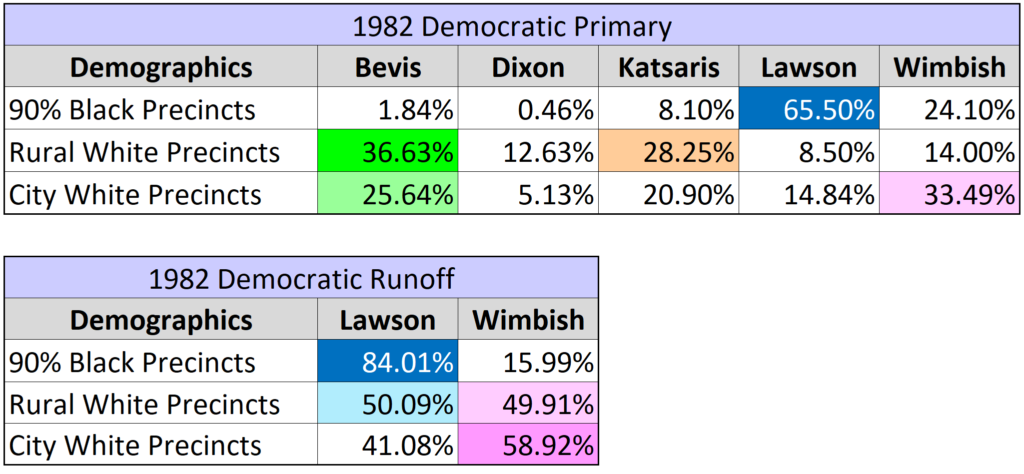

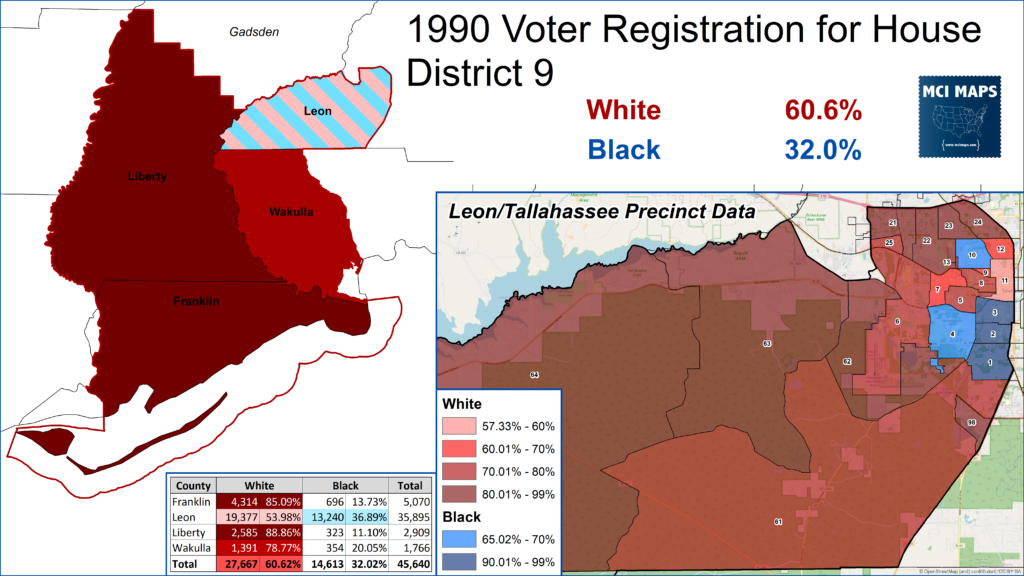

The racial makeup of the district’s voters can be seen below. This data if from the 1990s (earliest I could get uniform data sets for all counties) – but reflects the layout of the district though its lifetime.

Elections in Florida back then used runoff systems. This meant black voters could not rely on a divided white electorate. Top two candidates would go to a runoff. Considering the Democratic dominance in the region, only the primary/runoff mattered. It was no shock that no Republican filed for the seat. Instead, FIVE Democrats filed.

- Al Lawson – Insurance man and FAMU booster

- Bette Wimbish – Lawyer

- Rocky Bevis – Real estate executive and son of former Mayor

- Ken Katsaris – former Leon Sheriff

- Tookie Dixon – Real estate broker

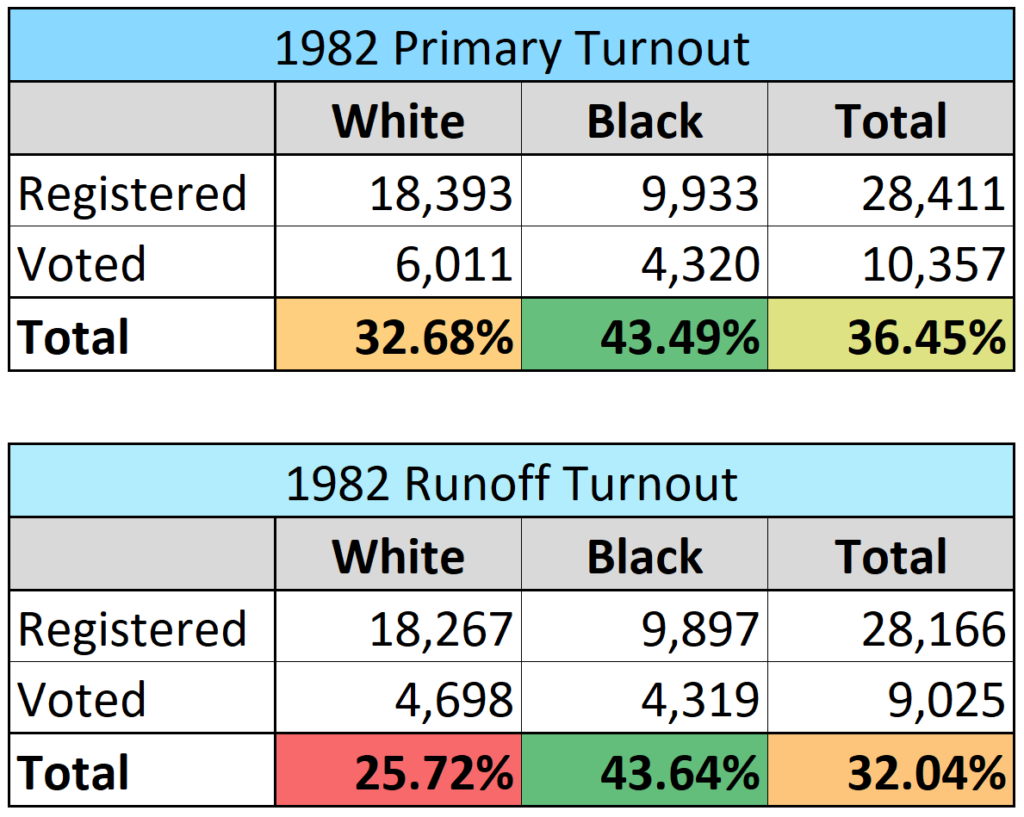

All five candidates engaged in heavy door-to-door campaigning, aiming to appeal to voters and secure a runoff spot. Candidates differed on issues but overall the campaign was positive. Black leaders worried that Lawson and Wimbish, both African-American, would divide the vote heading into a runoff. The solution was simple, work to turn out black voters as much as possible. The primary saw an organized effort to turn out the vote in the black community.

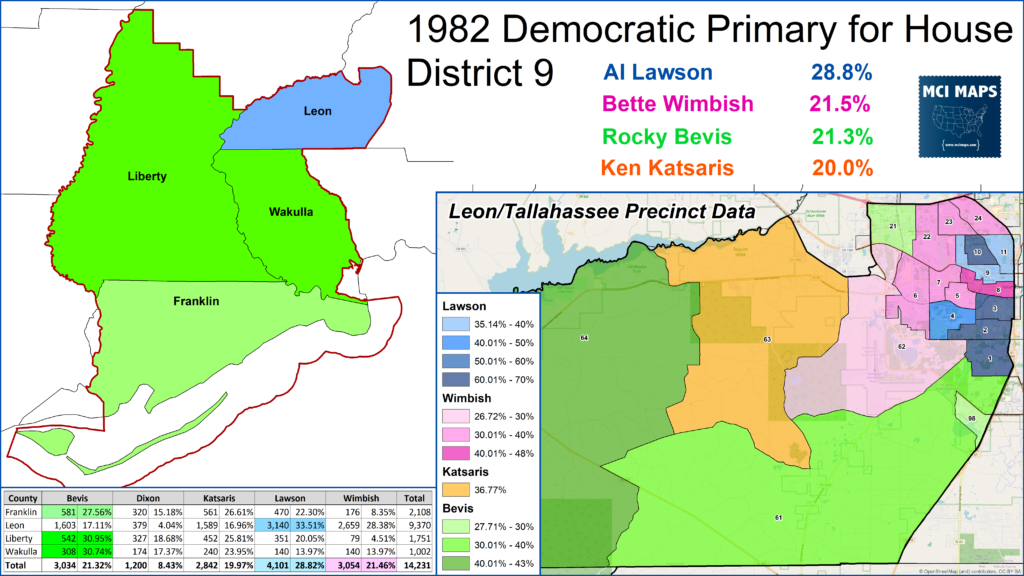

The first round of results saw Lawson and Wimbish advance to the runoff!

Turnout was a major break for black voters – especially in Tallahassee. As a result, black voters topped white voters in turnout in both the primary and runoff.

There is one critical caveat to this data. The white column includes Republicans, who had less to turn out for than Democrats (but this was the date of the statewide primaries). However, it is clear from reports on the ground and the available data that African-American voters were galvanized. This was a major African-American victory. However, the district was still very much a “shotgun marriage” of a seat – linking the city with the rural countryside. To me this story from the Miami Herald about the runoff sums up how different parts of this seat were from another.

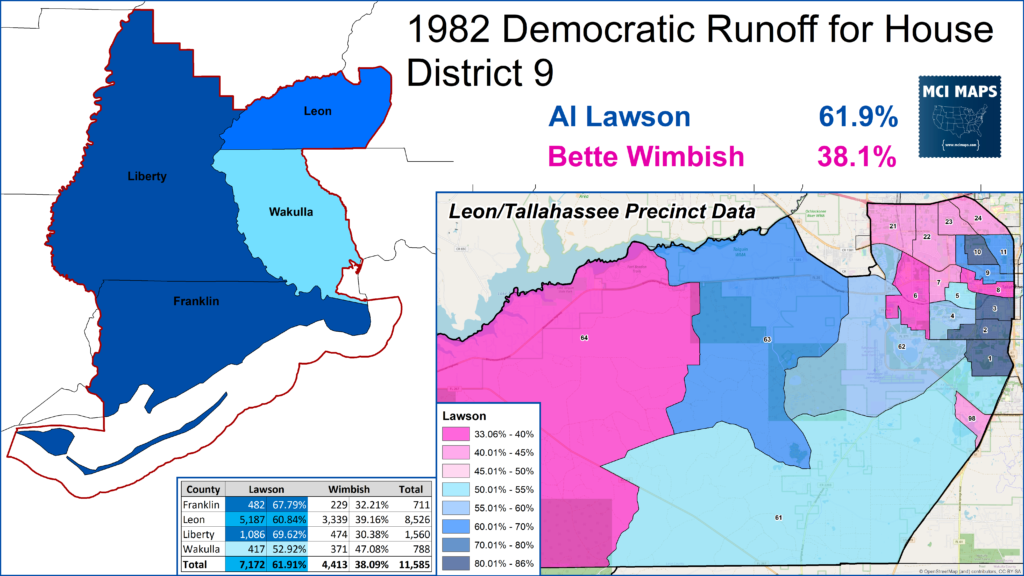

Lawson and Wimbish differed in one key way; their support bases. Wimbish was more of the candidate of middle class liberals, while Lawson was much strong with working-class black voters. Lawson’s position as the candidate of more working-class voters paid off for him in the runoff. Lawson wound up taking the runoff by a fairly comfortable margin. Lawson won the rural white counties; though the lack of precinct data makes it hard to determine how different votes in white or black precincts were. In the Leon precinct data, we see Lawson dominated in the heavily black communities of southside and Frenchtown. Wimbush won in the suburban precincts, and both divided up some of the rurals.

The rural precincts, however, also saw a notable drop in votes cast just a few weeks earlier. Clearly indicating many rural whites opted to sit out a runoff between two black candidates.

The precinct data for Leon reveals some important demographic aliances for the candidates. In both the primary and runoff, Lawson dominated in the African-American precincts. Wimbish, meanwhile, was strong with Tallahassee white voters, taking them in the primary and runoff. Lawson and Wimbish both did poorly with rural white voters, and in the runoff a good deal stayed home.

Lawson had no general election opponent. He won unopposed that November. With this victory, he became the first black state representative from the Tallahassee region since reconstruction.

1986 Election

After his 1982 victory, Lawson got a modest reprieve, as he faced no challenge in 1984. However, with 1986 came some new challengers. Lawson faced four opponents in the 1986 Democratic primary.

- Rocky Bevis – An opponent from 1982, the real estate lawyer and son of a former Tallahassee Mayor

- Arthur Floyd – A retired Florida Highway Patrol officer

- Joe Whitfield – A regional activists, band player, and avid hunter/fisher

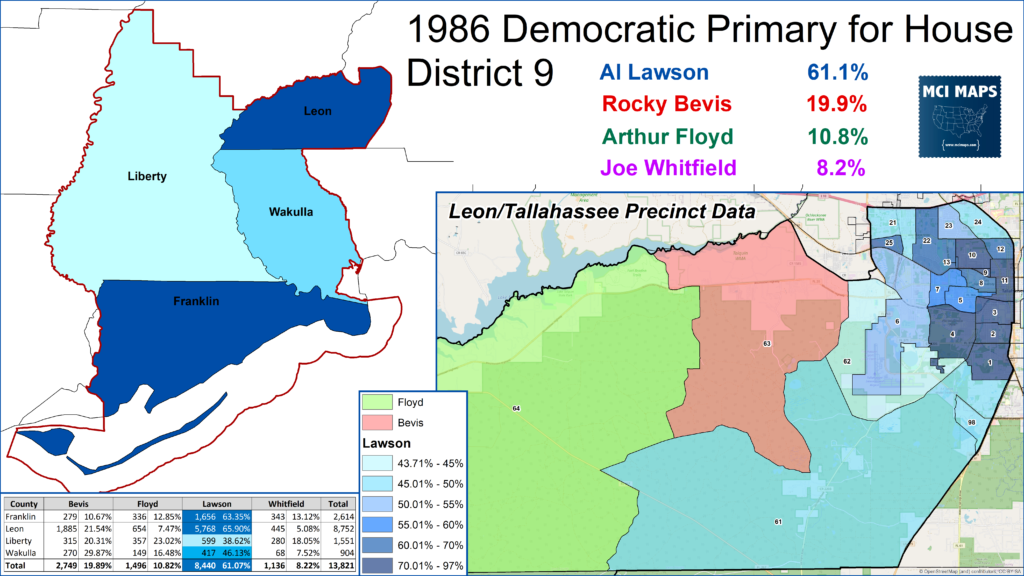

Lawson was the frontrunner from day 1 in this primary, with the real question being if he would make it to a runoff or win in the first round. Bevis was especially negative in the campaign. The main source of attacks was that Lawson continued to operate his small business while a lawmaker, and questioned if Lawson was using his office to generate revenue to his firm. The simple fact is state house members are part time and pay is not enough to live on. Lawson was never accused of any crime, and Bevis’ attacks eventually came off as too bitter and nasty. One attack was over Lawson using official stationary to send out cards for a big Christmas party. However, the funds for that came from an account all members have for such community outreach.

One of the nastier attacks from Bevis was over “The North Florida Black Pages.” This was a directory of minority owned businesses in the region that Lawson printed/ran and was paid for by advertising. Bevis accused Lawson of using his position to direct lobbyist donations. However, records showed the total funds in advertising were under $10,000 a year; and no evidence of pressure from Lawson ever emerged.

The Bevis attacks likely backfired, and Lawson easily won the Democratic primary, taking 61%. In the end Bevis came off too negative, and concerns about advertisers meant little when Lawson was able to bring in funding for different issues across the district. Lawsons success in steering millions for airport improvements in Tallahassee blunted Bevis’ attacks.

Lawson dominated the vote in the African-American community and did well in the white suburbs of Tallahassee. He only lost ground in the more rural precincts; which match with low shares in Liberty and Wakulla County. However, he did especially well in Franklin. This is a great example of his constituent work paying off. Not long before the primary, Lawson was honored in the coastal town of Carrabelle for helping steer funds to a much-needed sewage treatment center and some port repairs. Coastal counties like Franklin had/have unique issues that Lawson was able to help with and was rewarded with support.

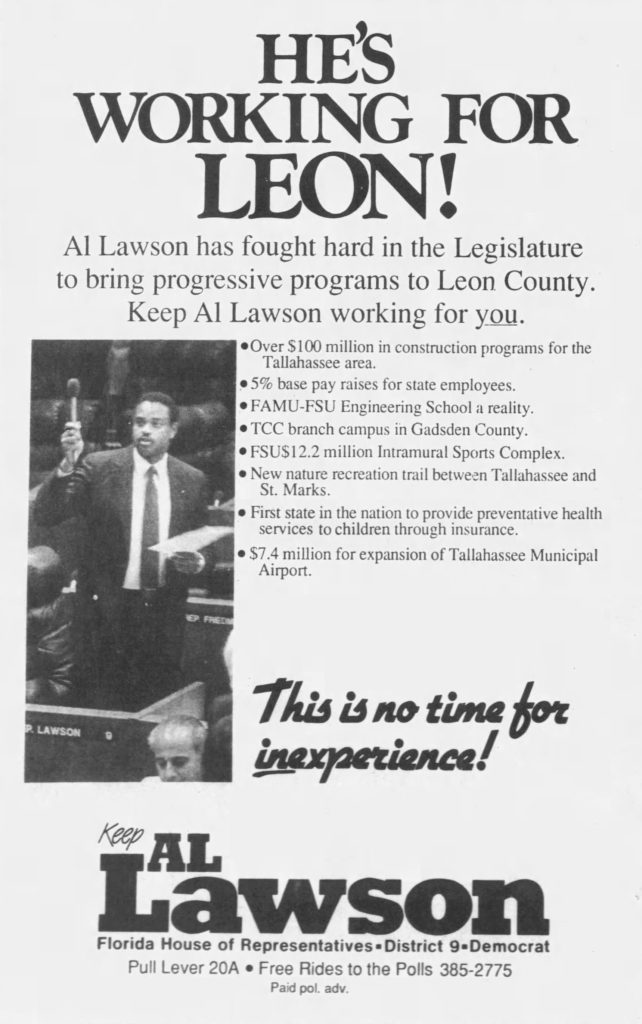

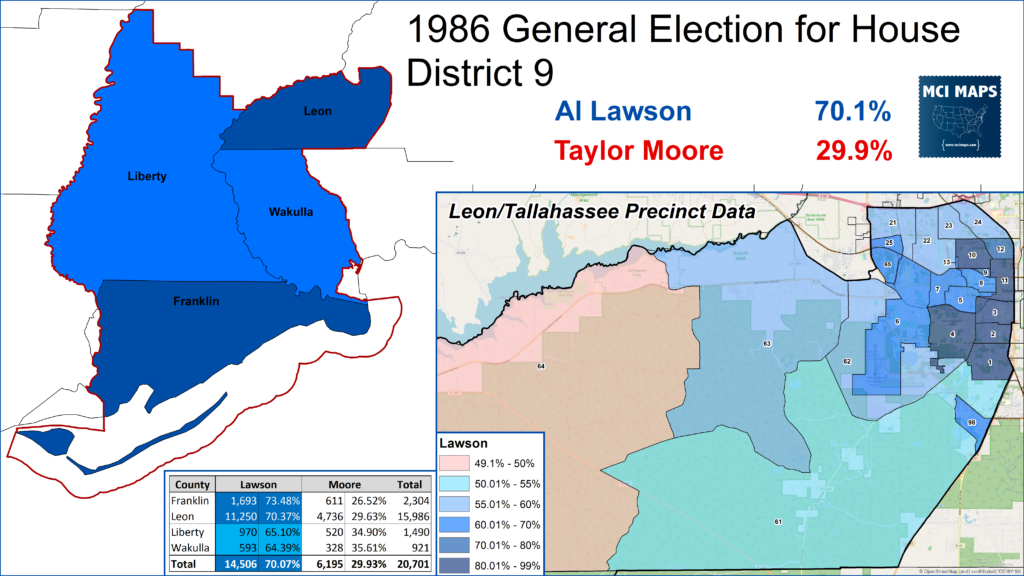

Lawson would actually have a general election opponent. This race was a nothing from the start, however. Lawson had emerged from the primary in a strong position in a seat where the district was overwhelmingly Democratic. Republican Taylor Moore’s biggest line of attack was a repeat of Bevis’ lines and also hit Lawson for not yet being in the House leadership. This was true, Lawson was not a leadership insider at this point. However, Lawson blunted this line of attack (which aimed to say Lawson wouldn’t be able to do enough for the area) by touting his accomplishments. Ads like this were very common.

Lawson easily won the race, taking all counties. He did lose the precinct for the community of Ft Braden in Leon.

Lawson would have no real threats after this. He’d face no opponent in the 1988 elections.

1990 Election

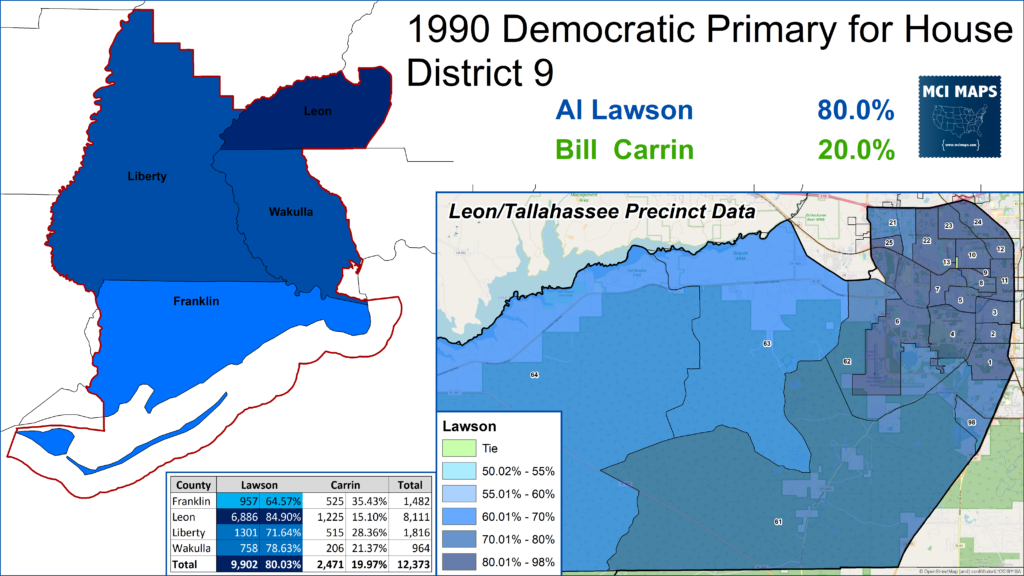

Lawson faced the very definition of token opposition in 1990. His Democratic opponent, Bill Carrin, didn’t run a serious campaign; doing few events and largely being unseen on the trail. In the meantime, Lawson had risen as Chair of the House Natural Resources Committee was viewed as a strong advocate for district issues. He easily won the primary.

No general election opponent filed. This would be Lawson’s last real contest for a decade.

1992 Redistricting

After the 1990 elections, redistricting began in Florida. The redistricting saga in 1992 in Florida is a chaotic mess. I wrote about the legislative and congressional redistricting in the linked articles. Lawson and the rest of the black caucus were major players in the process. The Democratic majority in the legislature, which was rapidly losing seats as the GOP rose in modern strength, was desperate to gerrymander themselves into a secure majority. This was in conflict with the 1982 Voting Rights Act amendments that aimed to improve the chances for minority districts to be drawn. The white democratic leadership could no crack black voters to use them to boost DEM margins in multiple seats. The result was a notable increase in proper minority seats. This was seen in Tallahassee, where African-American voters finally got the Gadsden-Leon district they were asking for.

For Lawson, running in this new HD8 was no problem. It includes the Tallahassee base he already held, and adding in his home county of Gadsden. Lawson told the papers how happy he was, talking about how he’d be able to represent his family in Gadsden. Lawson opined “This district is like a homecoming for me.”

Lawson would never face a challenge for his seat. Outside of a 1998 write-in challenger, Lawson won all re-elections without opposition.

Eyes on the State Senate

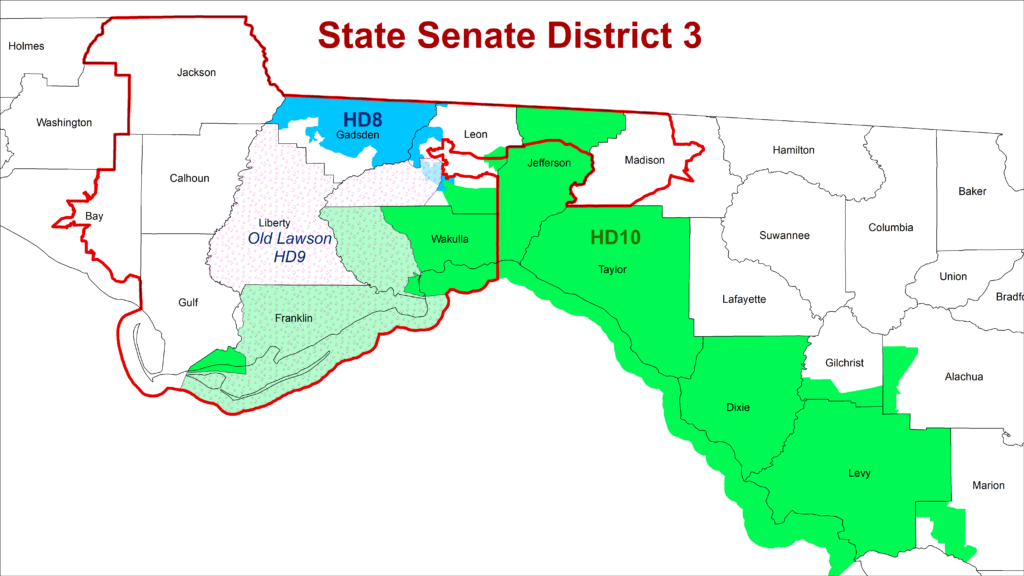

Once in his new district, it was clear Lawson had his eyes on the state senate. The region was covered by two senate districts; and it was widely believed that Lawson had his eyes on SD3. The seat covered the black population of Leon and Gadsden and included many of the western-of-Leon counties Lawson already had ties in. In 1992, the incumbent for the 3rd was Democrat Pat Thomas, who’d served in the legislature for twenty years. Thomas got a primary challenger from former Tallahassee commissioner Jack McLean. Lawson backed Thomas over McLean for that run. Thomas was on course to become Senate President, with many expecting the Senator could step down after his tenure in that office was up.

Unfortunately for Lawson, Thomas would opt to serve until term limits kicked in in 2000.

1996 Redistricting Drama

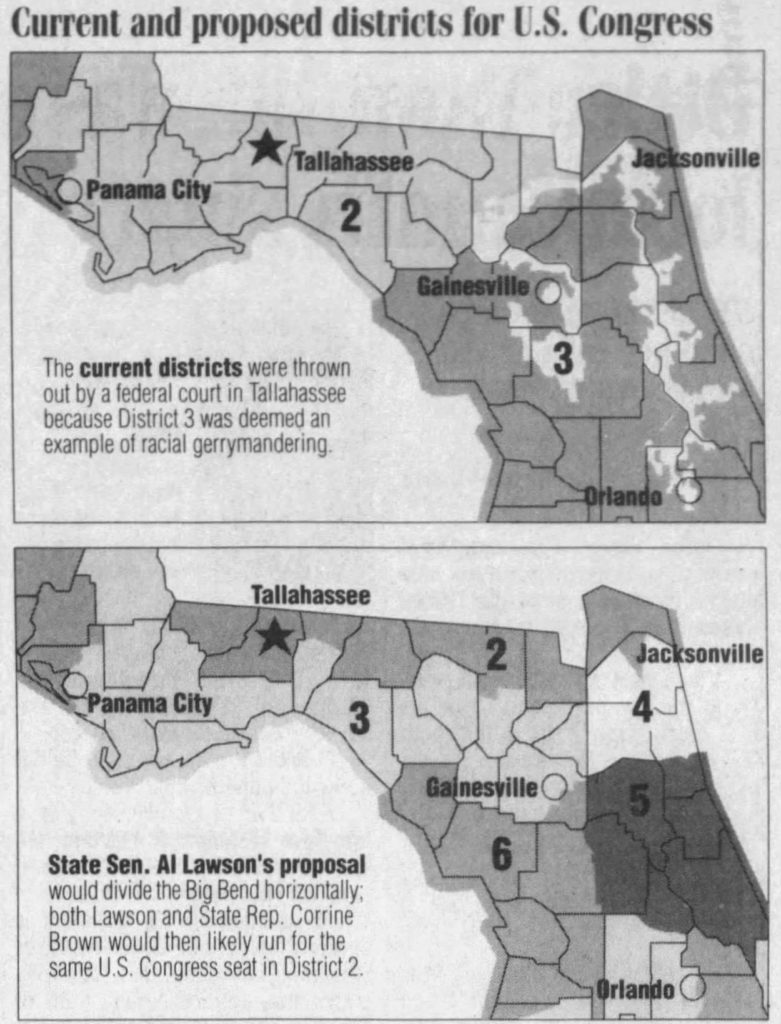

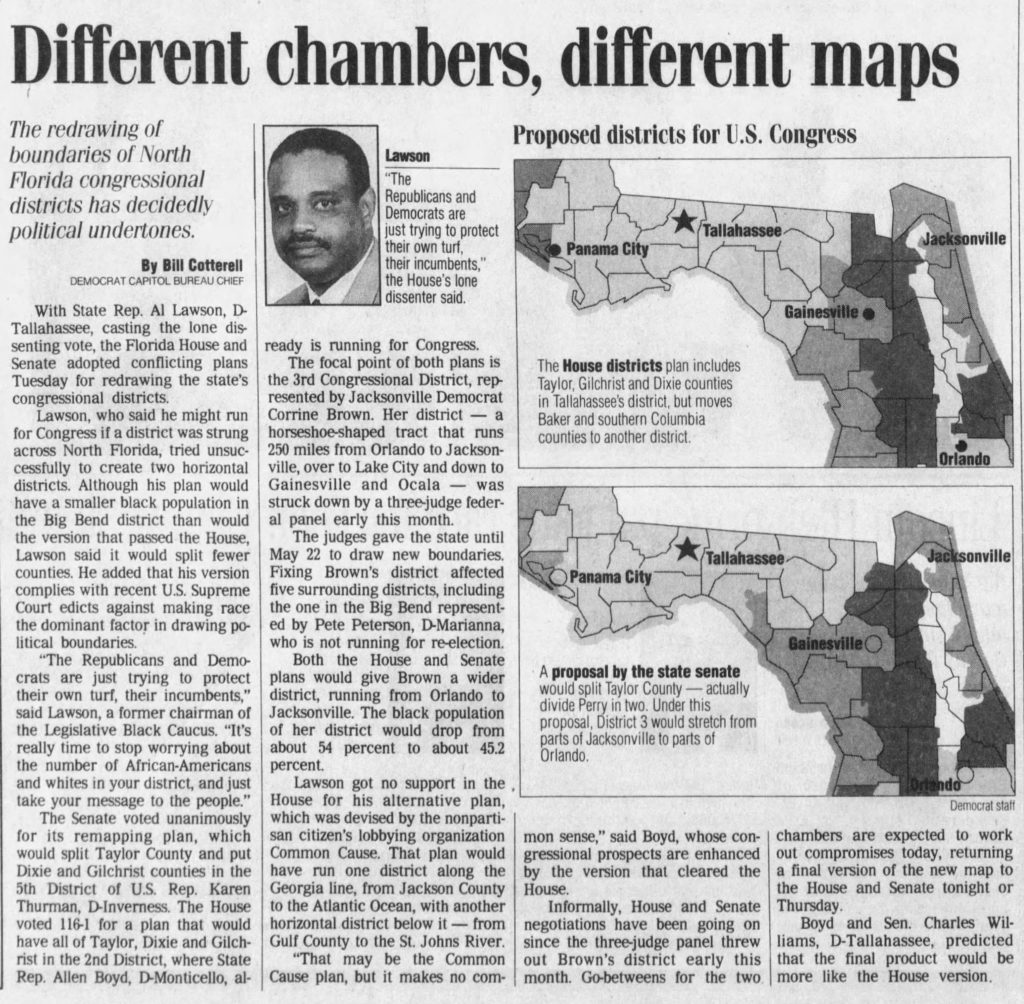

As Lawson sat in the state house, a new development emerged, one that would shape north Florida politics for decades. In 1996, Florida had to redraw its Congressional lines. Corrine Brown’s 3rd district was struck down for being a racial gerrymander. It was ruled the seat was too bizarre to be justified, and a new layout was needed.

Many lawmakers had takes on how the new districts should look. The goal was to change the bare minimum, with North Florida getting the biggest changes. FL-02 Congressman Pete Peterson was retiring, giving North Florida politicians incentive to draw the lines to benefit themselves. This marked the first major conflict between Al Lawson and Allen Boyd. At the time, Boyd was a State Rep for District 10, which covered the regions east of Tallahassee.

Boyd was Chairman of the House rules committee, and as such could block any map from making it to the house floor. Boyd had his eyes on the 2nd district, and wanted to ensure the 2nd was changed only slightly; namely keeping rural, Democratic places like Taylor and Dixie within the district. Lawson, meanwhile, wanted an east-west configuration for the 3rd (similar to what we have with today’s 5th) that could allow him to challenge Brown. This would leave the 2nd snaking under it. Such plans were also debated in the 1992 session itself.

Lawson’s push, however, had no support. Instead, the debate focused on the Senate and House differences. The Senate plan cut out some rural, Democratic communities Boyd wanted.

In the end, the legislature opted for the House plan, which gave Boyd the district he wanted. The focus of this session was Brown’s 3rd district, but both plans were considered acceptable changes. The real drama became the 2nd and the Florida panhandle.

Boyd would go on to win the 2nd district, defeating Leon’s first black female county commissioner, Anita Davis. Boyd’s sister-in-law, Janegale Boyd, would win House District 10.

Lawson would continue to sit in the state house — until 2000.

State Senator

2000 Campaign

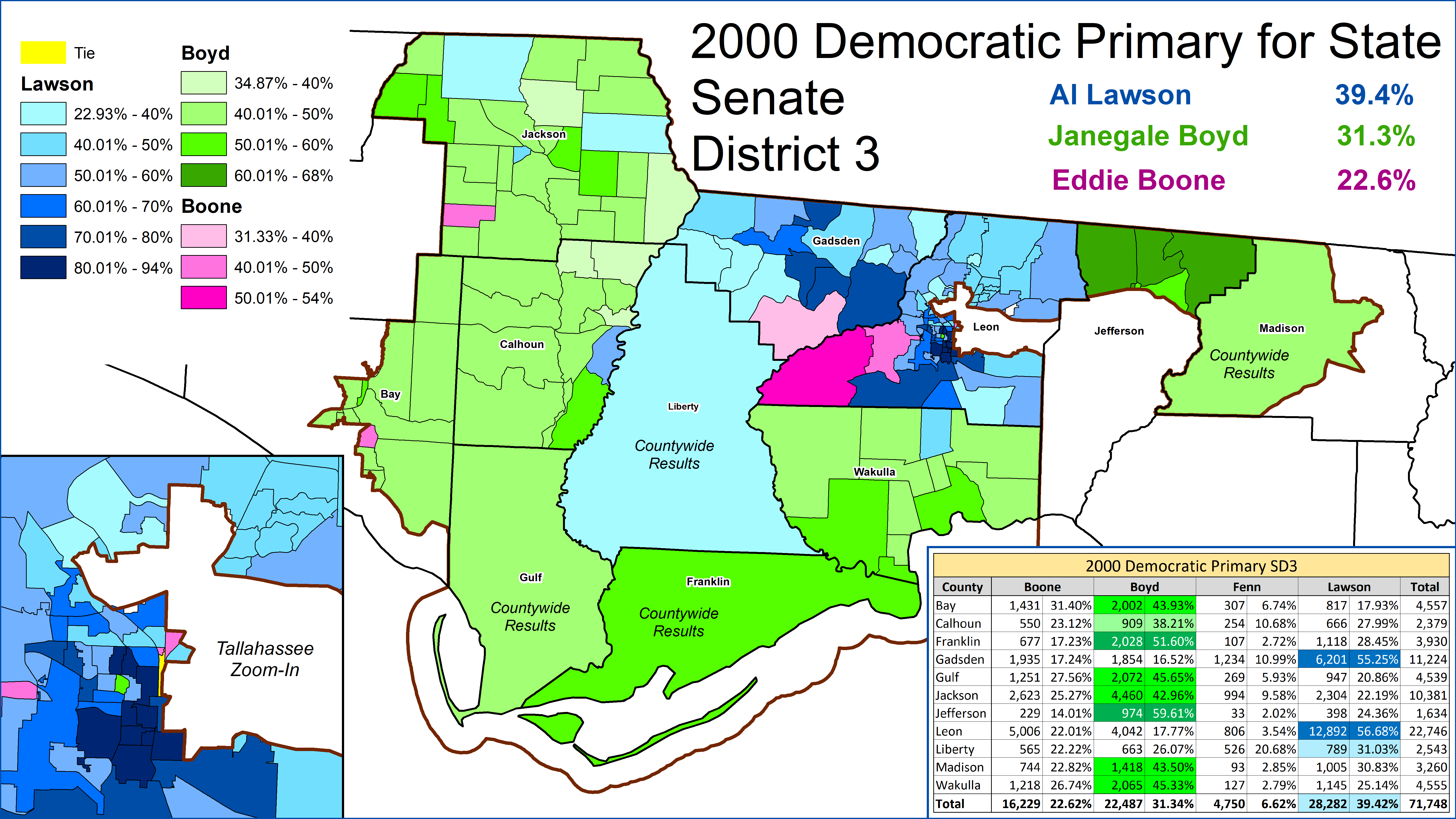

In 2000, incumbent State Senator Pat Thomas would retire due to term limits. This set up a major primary for SD3. Three major candidates emerged.

- Al Lawson, the current HD8 representative

- Janegale Boyd, the current HD10 representative, sister-in-law to Congressman Boyd

- Eddie Boone, former Leon County Sheriff

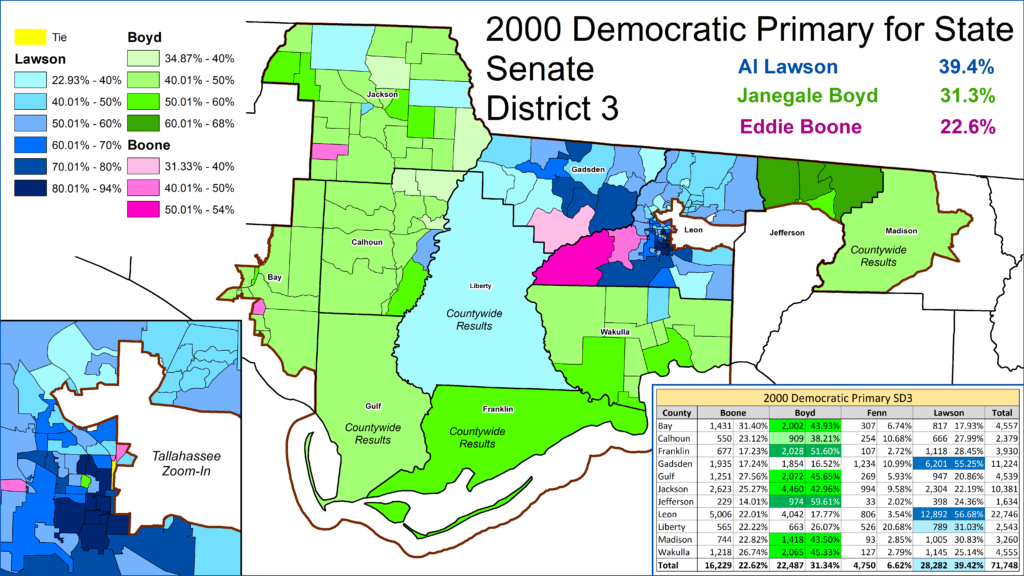

All three candidates had bases of support.

This was a mega-money fight, with Lawson taking in over $200,000, Boyd over $450,000, and Boone over $250,000. In addition, outside money poured into the race from different interest groups. The race was largely viewed as a contest between Lawson and Boyd, with a runoff widely expected. Boone was the target of attacks from the Police Benevolent Association for anti-union positions; an attack that drew the ire of the then-Sheriff Larry Campbell. Boone and Campbell were much more conservative democrats. Different interest groups fought over Boyd and Boone; with everyone expecting Lawson to be guaranteed a runoff spot. Boyd was subject to many attacks from trial-lawyers for her opposition to the ability of patients to sue HMOs. In the September 5th primary, Lawson and Boyd advanced to a runoff.

Lawson and Boyd both told the press on primary night that they hoped the runoff would be a more cordial and issue-focused affair; with no mudslinging. Oh boy did that not come to pass.

The runoff was a major clash in styles. Lawson was a long-time representative for the region and by far the more liberal candidate with less big-money support. Boyd was one of the more conservative Democrats in the house and had far more financial backing. Lawson did have backing from major unions, and his liberal record earned him the backing of the National Organization for Women. Lawson ran a very aggressive grassroots campaign; hitting events and knocking on doors. Lawson touted that if he won, which would make him the first black senator from the region since reconstruction, it would be a major inspiration for young African-Americans in the region.

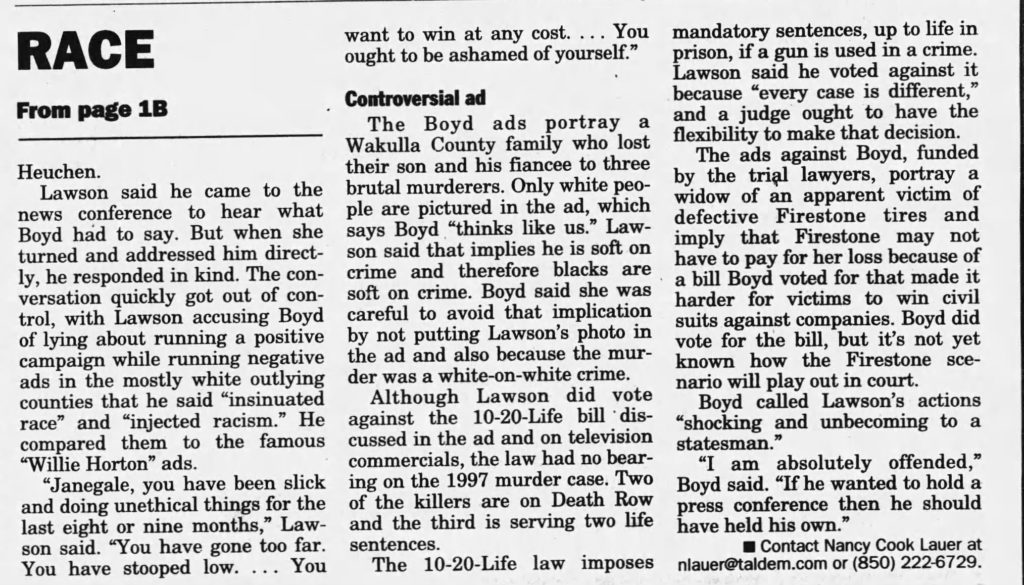

Negative attacks dominated the runoff; many from third party groups. Firestone Tire became a major story in the runoff. For those unfamiliar, Firestone tires went through a massive crisis in the late 1990s as it was revealed a large number of tires were defective, leading to accidents and deaths. This brought attention on Florida’s late 1990s tort-reform laws; which aimed to limit the amount of money that could be won in lawsuits. The result? An trail-lawyer ad featuring the widow of a firestone tire victim attacking Boyd for supporting that reform. Lawson had constantly voted against tort reform.

Additional attacks were laid on Lawson as well. The NRA ran adds hitting Lawson on gun control and Boyd herself ran ads hitting Lawson for opposing the mandatory-minimum-esq 10-20-life guidelines in Florida. On September 29th, not long before the runoff, tensions exploded. Boyd called a press conference to decry the ad being run about the firestone controversy. Lawson was in attendance, and when she addressed him, he argued back. Lawson brought up Boyd running racially-tinged ads in the rural counties; which featured a white family who lost a loved one criticizing Boyd for his supposed “soft-on crime” positions. Boyd claimed she had no intention to bring race into it.

Lawson made his views clear

“It’s like Willie Horton all over,” ………. “It’s outrageous. Someone lost their kids, and you say if I voted for that bill, they’d be alive today.

Al Lawson

You can read more on the whole episode here.

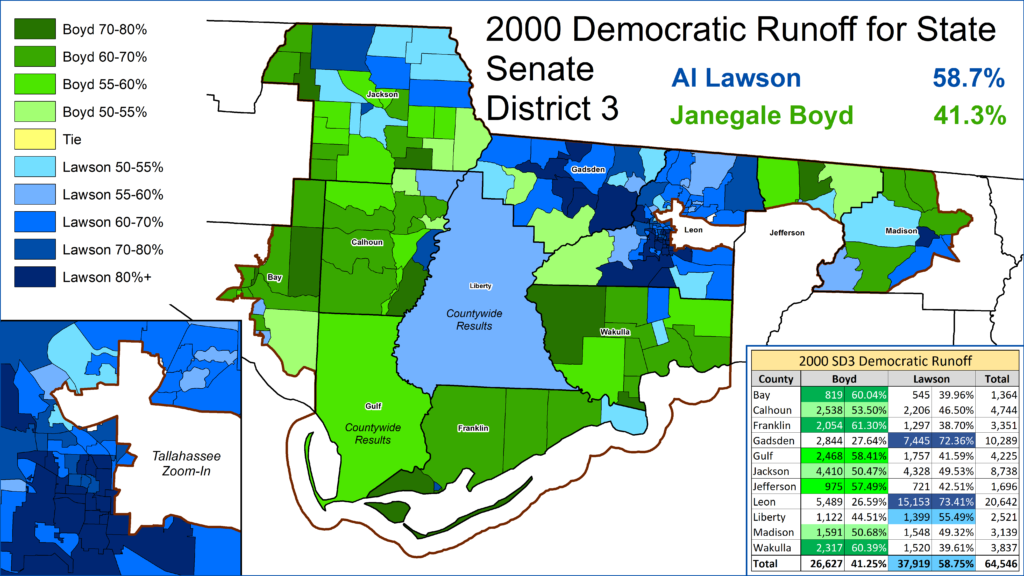

A few days later, on October 3rd, the runoff took place. Lawson won by a solid 16 points, fueled by huge margins in Leon and Gadsden counties.

Lawson dominated in Gadsden and Leon, which made up just under half the entire vote. His 70%+ margins there could not be matched by Boyd in the rural white counties. Lawson also took Liberty county, a reflection of his time representing the county in the past.

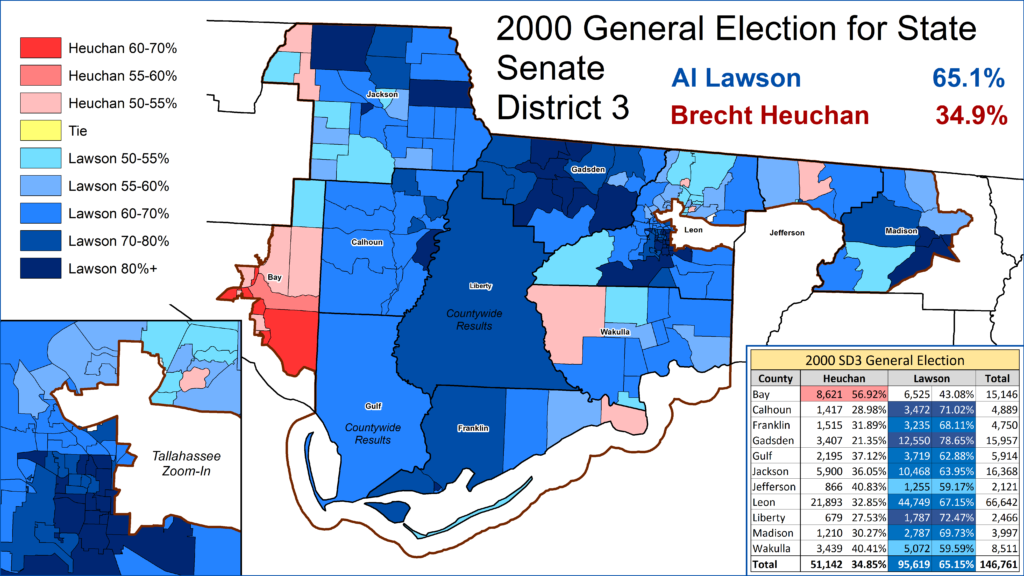

With the runoff over, Lawson was a lock for the general. The district had a 4-1 Democratic registration advantage. While it would be closer for the Presidential race, this was still in an era of down-ticket Democratic advantage. Lawson’s opponent was Republican Party staffer Brecht Heuchan.

Lawson won the seat by a resounding 30 points, even as Al Gore only won the seat by 4%. Lawson continued the Democratic tradition of down-ballot success.

Lawson would face no opposition in for his seat from that point on. His seat would see some redistricting changes in 2002, but the broad district remained the same. Lawson would eventually be elected as the Democratic leader of the Senate Democratic caucus.

Termed out in 2010, Lawson turned his eyes to Congress.

Congressional Attempts

2010 Democratic Primary

Lawson was going to be termed out of the state senate in 2010. This fact, plus the bad blood that existed between the Lawson and Boyd camps, resulted in Lawson opting to primary Congressman Allen Boyd for the Congressional seat. Boyd had already generated Democratic grumblings with his more conservative voting record. Key votes that angered left-leaning Democrats were his support for the Iraq War and Social Security Privatization. Lawson’s primary had the advantage of being able to unite left-wing whites in Tallahassee and African-Americans. Boyd, meanwhile, would benefit from the rural, conservative Democrats outside of the city,

The campaign had its share of heated moments; with supporters of the candidates on constant edge. However, the campaign never reached the nasty levels of 2000. Boyd’s 2009-2010 voting record helped him against Lawson. Boyd backed Obama on the Stimulus Bill, Cap and Trade, and the final votes on Obamacare. There were plenty of awkward moments, however. In one instance, Michelle Obama was sent to campaign with Boyd, though she didn’t realize it was an actual campaign event. In another instance, Lawson took the camera away from a campaign tracker. Boyd called the police, but the incident was brushed off and camera replaced. In another instance, Lawson took a dig at Boyd’s divorce – ok that was petty. These two didn’t like each-other.

The Obamacare vote very likely helped Boyd in the primary, but also hurt him in the general. Boyd did take a hit, however, for rejecting the reform in November, but backing the final vote in March. The bill did have notable differences, but such optics always look bad (fair or not). Lawson could not resist – quipping “He’s been a great fence-rider.” Nevertheless, these votes greatly alleviated left-wing anger at the Congressman.

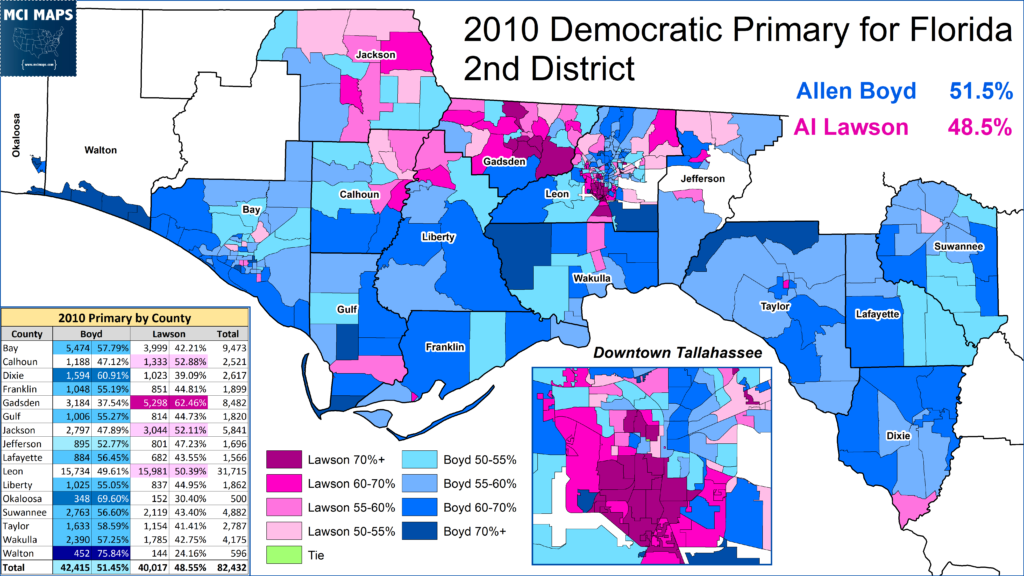

Since the seat had backed Bush and McCain in the Presidential elections, Boyd’s argument that he was needed to hold the seat appealed to tactical voting. Boyd had far more cash than Lawson, and spent over $2 million in the primary compared to Lawson’s under $250,000. The final results were a narrow Boyd win.

Boyd won the primary, but in a very narrow way that screamed vulnerability. Not only did Boyd lose the black vote, he didn’t crush Lawson with rural whites. Boyd, like many southern Democrats, was getting hit as a DC insider, and many rural white voters cast protest votes against Boyd. Boyd, however, did himself favors with his Obamacare vote. He won in many of the liberal, white suburbs of Tallahassee; with many longtime activists feeling compelled to reward the Congressman for standing with the President.

The Lawson v Boyd primary deeply divided the region’s Democrats. Boyd would go on to lose the general election. How much of this is Lawson’s fault? Well, realistically Boyd’s 10% loss means the red wave was likely to doom him anyway. However, that did not change the hard feelings that emerged from the contest. Lawson, meanwhile, was out of office for the first time since 1982.

2012 Election

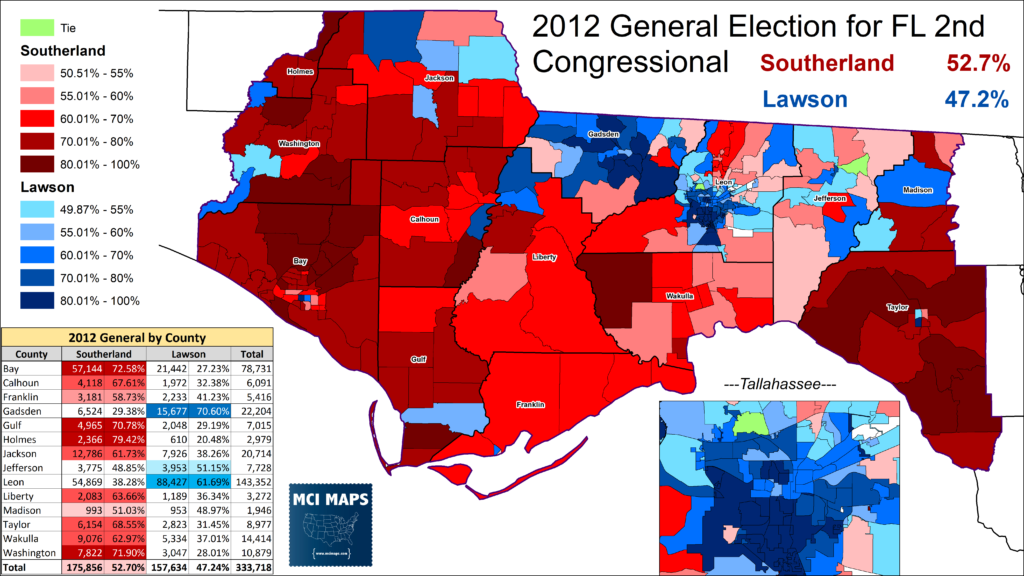

After 2012’s redistricting – read my coverage here – a new 2nd district was in place. The seat was largely the same as the old district, but now Leon and Jefferson counties were whole. The seat still leaned red at the top of the ticket, but Democrats hoped they could make Republican Steve Southerland a fluke Republican. Boyd declined a return bid for office. Lawson was in.

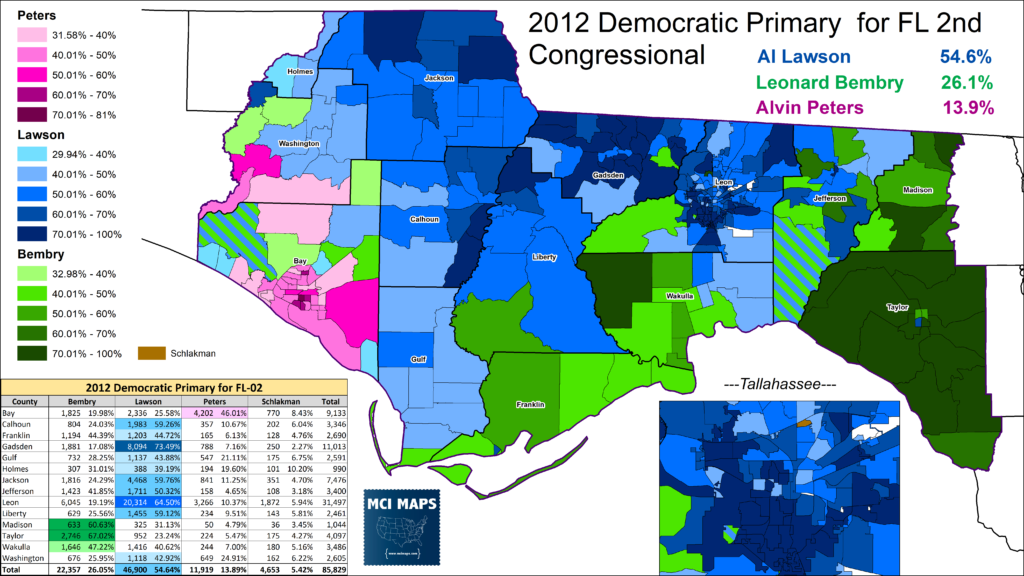

The DCCC, meanwhile, recruited State Rep Leonard Bembry to run for the office. Bembry, the most conservative Democrat in the legislature at that point, represented HD10 – a region similar to Allen Boyd’s original seat. There was no love for Lawson among national Democrats after the 2010 primary, but Lawson did not care. Bay County Democratic Chairman Alvin Peters also jumped into the race. While Peters had less funds, he proved popular with liberal whites who thought Bembry was too conservative but were also angry at Lawson for 2010.

For all the drama around the primary, the results were a blowout. Lawson easily won the primary. Lawson dominated not just in the African-American community, but across much of the western counties he already had ties in. Bembry was more limited to the eastern white, rural precincts. Peters, meanwhile, did secure his Bay County base.

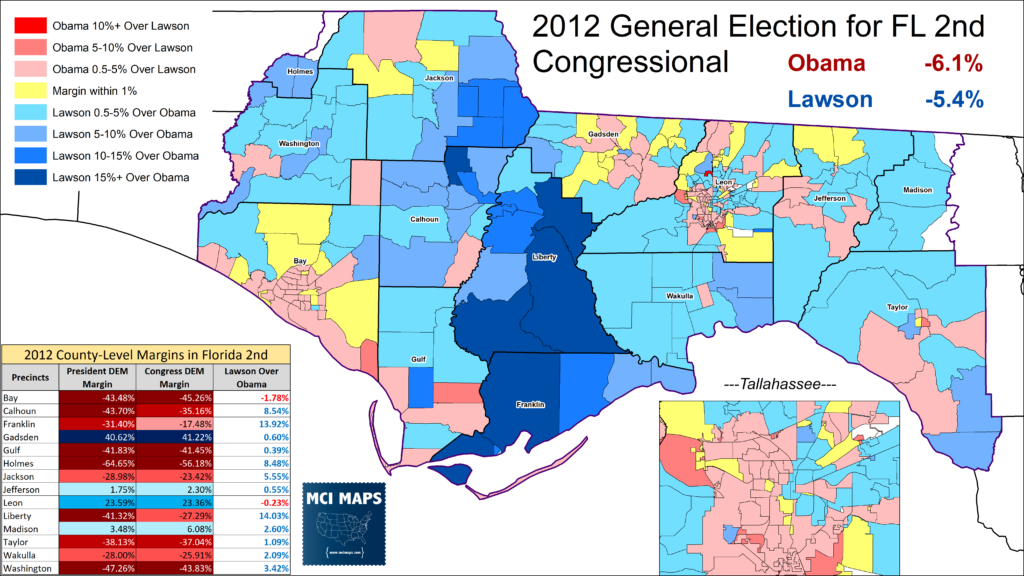

With the primary settled, Lawson secured support from national Democrats. The race between Lawson and Southerland was considered a major Democratic target. However, as the general took shape, the seat remained in the Lean GOP stage. It was widely understood Obama would lose the 2nd district, even if he pulled off a Florida win. Lawson would need cross-over support to pull off a win of his own.

When the results came in on election day, however, it was clear Southerland had won.

Lawson was able to narrowly outperform Obama in the the district. However, his biggest improvements were in the rural counties he represented in past seats. His major over-performances in places like Liberty and Franklin were not enough to secure the seat. Bay County, the home to Southerland, had the biggest underperformance for Lawson.

With this loss, Lawson was, for a brief moment, out of the electoral realm. 2014 was the first time since 1980 that Lawson was not a ballot. He considered a rematch for CD2 in 2014, but as national Democrats rallied around Gwen Graham, Lawson backed down from such a move.

It wasn’t clear at this point if Lawson would have any more electoral fortune. Then came Florida’s court-ordered redistricting.

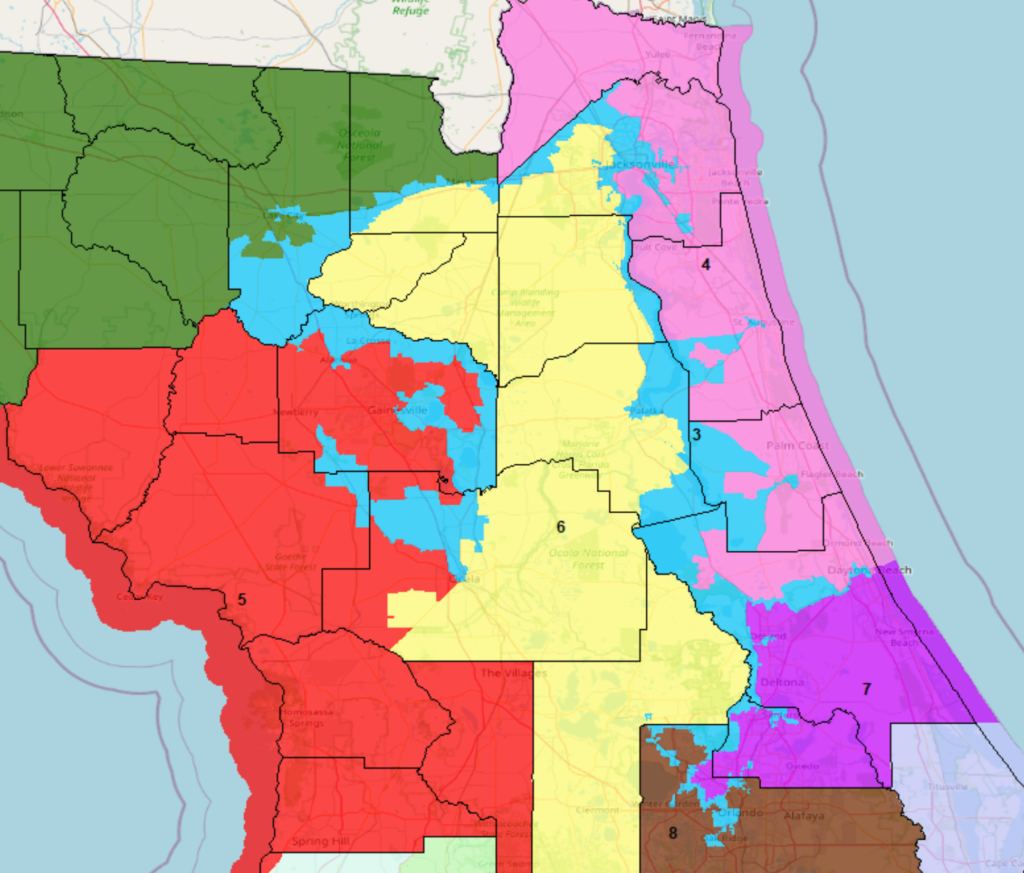

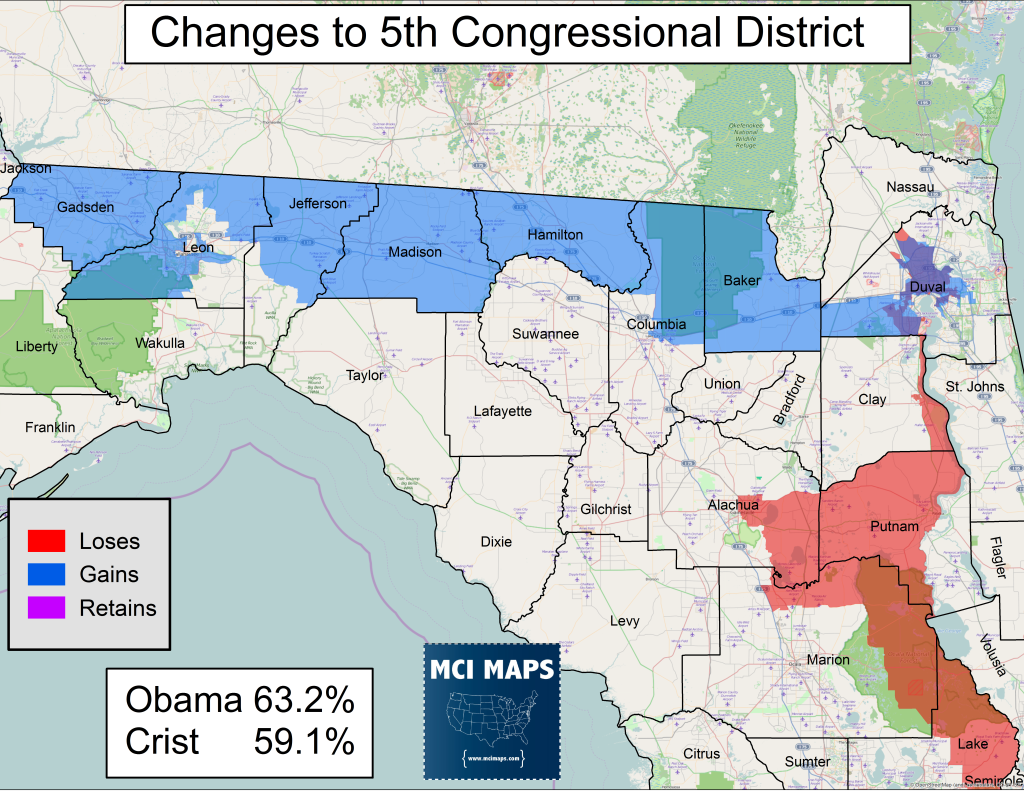

Congressional District 5

In 2015, the Florida Supreme Court struck down Florida’s Congressional plan. I wrote all about this in this redistricting history article. So I recommend reading that if you are not familiar on the details. The long story short is that the court struck down Corrine Brown’s Jacksonville-to-Orlando district; instead ordering an east-west configuration. The logic behind this order was that east-west would maintain a minority-access seat for African-American voters; while removing the partisan taint of Republicans protecting their incumbents in Orlando. This ordered followed the legislature getting busted violating the 2010-passed Fair Districts Amendments. The new redistricting rules forbade partisan gerrymandering; but mandated maintaining minority representation. This was the resulting Florida 5th district. The seat was heavily Democratic and over 60% black in a Democratic primary.

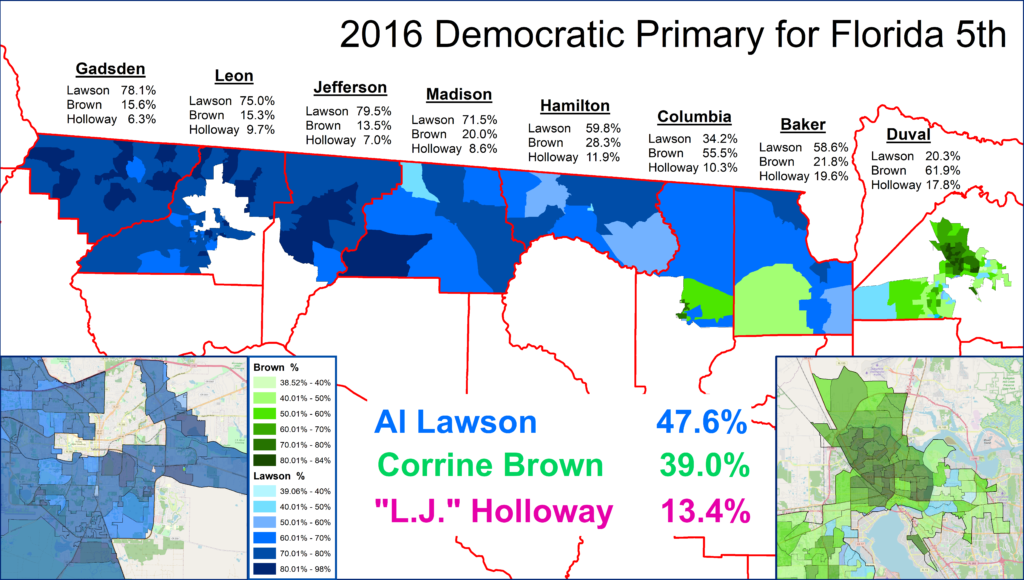

2016 Election

By the fall of 2015, it was clear what the 5th district would look like. Jacksonville’s Corrine Brown was going to be forced to run in a seat where she had little ties to the western counties. Democrats from Tallahassee mulled how to approach the seat. Only one western candidate could run, otherwise a divided west would mean a guaranteed Brown win. The top candidate names floated were Lawson and Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum. From what I have gathered, both men wanted the seat, and efforts were underway to ensure only one of them ran. Lawson was the veteran who arguably “deserved” the first pass. Gillum was young the up-and-coming “rising star” in the party. So how would they decide?

Well, in August, Lawson just went ahead and announced he was running! This trapped Gillum, who knew that announcing a bid of his own would just mean a divided west and Corrine Brown victory. With no real option, Gillum did not run for the seat. This set up a major battle between Lawson and Corrine, who’d served together in the state house in the 1980s.

As I went over in my 2015 redistricting article, Brown was livid with her new district. She made many easily-disprovable claims that the seat would not elect an African-American. Lawson rapidly secured support across the western counties and it was believed both candidates had a shot at the seat; with internals showing a dead heat. Then, in the summer of 2016, Brown was indicted for fraud revolving around a “charity” being used as a personal piggy bank. It was the final nail in the coffin for her. She lost the primary to Lawson.

Lawson’s victory was thanks to massive margins in the western counties. Brown, meanwhile, lost ground in Duval, which made up 50% of the votes cast. Brown only secured 60% in Duval, with third candidate L.J. Holloway serving as a protest vote.

Lawson had zero issues in the general. This was a seat that was over 60% Democratic up and down ballot. Lawson finally had made it to Congress.

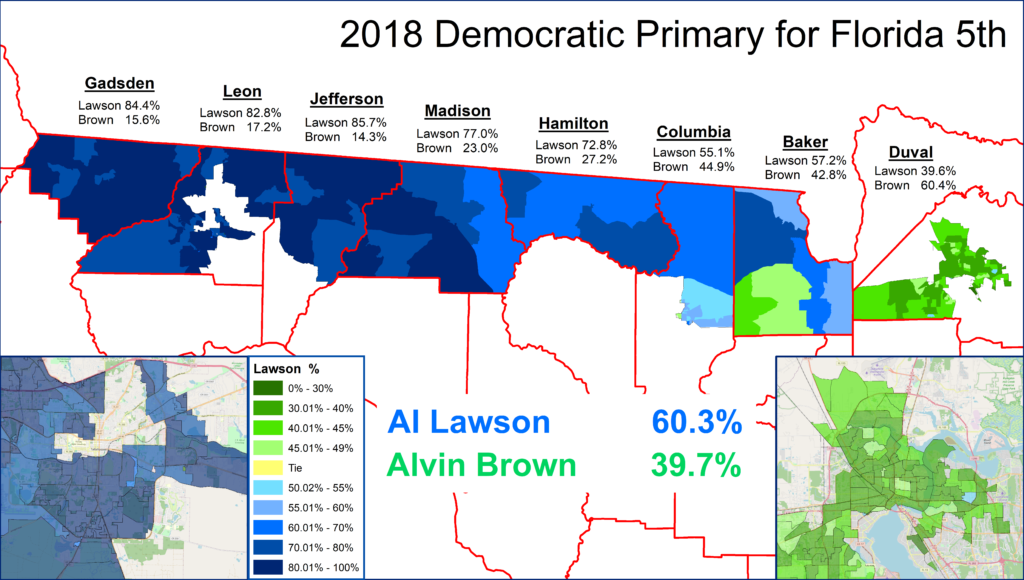

2018 Election

Lawson went into the 2018 elections viewed as a frontrunner but not a lock for re-nomination. It was well documented that Jacksonville was angry at losing their Representative in 2016. The question became, who would run against Lawson. In 2017, former Jacksonville Mayor Alvin Brown announced he was running for the seat. Brown had been elected Jacksonville Mayor in 2011, but lost a contentious runoff to Lenny Curry in 2015. Brown’s failed re-election came as he was in conflict with the LGBT community of Jacksonville; a reaction to him not backing a Human Rights Ordinance. Brown came from a more religiously conservative wing of the party, which is strong in the African-American churches of the city. This allowed Lawson to make inroads in Jacksonville; running to the left of the mayor. Brown entered with big flair, but Lawson promised to retire Brown for good. He did just that.

Lawson continued to dominate in the western counties. Brown’s share of the vote came almost entirely from his 60% win in Jacksonville. This marked a strong improvement for Lawson, however, as he secured 40% in the county.

Like 2016, Lawson had zero trouble in the general.

2020 Election

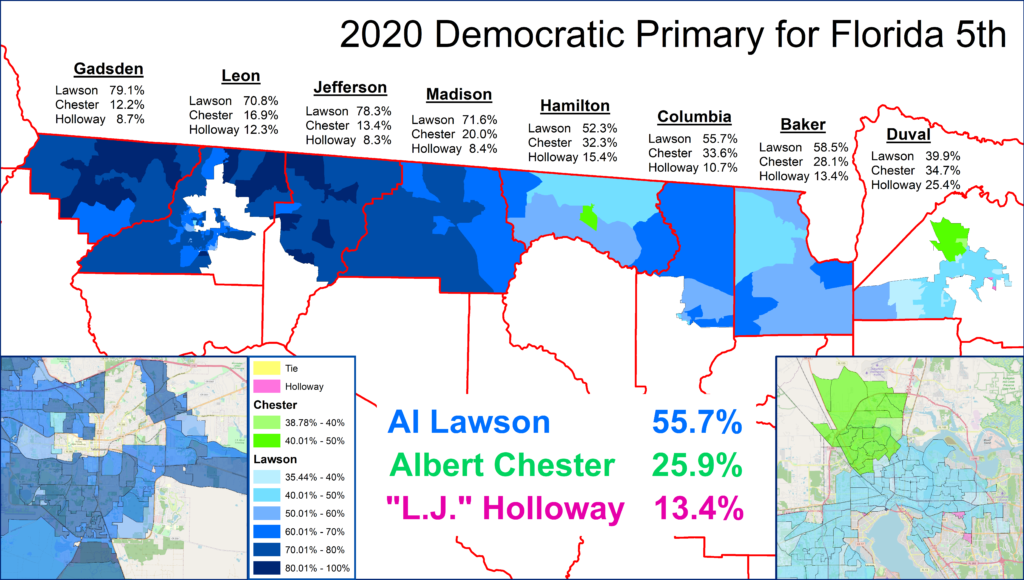

Lawson’s most recent campaign was a fairly quiet affair. As COVID hit America and focus was glued to the Presidential contest, Lawson generated two Jacksonville challengers. Businessman Albert Chester and former candidate L.J. Holloway took on Lawson, but neither were given much of a shot at winning. This did mark the first time Lawson ceded some ground in the Tallahassee region. Chester and Holloway aimed to run to the left of Lawson, who by and large is a fairly moderate democrat. However, unlike a Manchin, Lawson never gets caught being on the wrong side of big votes. In the end, needling of Lawson did not have any big impact, and he won re-election.

Lawson’s 55% wasn’t stellar, and its hard to gauge how much of that is Lawson not campaigning hard, COVID limiting outreach, left-wing rise in the Democratic party – or a little of it all.

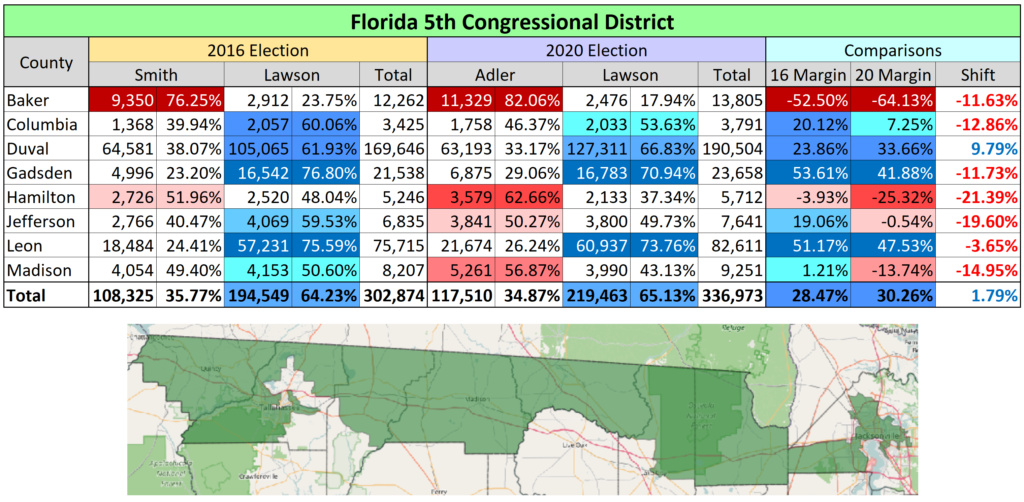

One of the notable changes for Lawson has actually been in general elections. From 2016 to 2020, Lawson’s general election margins remained almost exactly the same; 30 point wins. In fact, Lawson won by 1.8% more in 2020 than he did in 2016. However, when looking at the data by county, we see huge swings.

Lawson lost a tremendous amount of ground in the rural counties. He won Jefferson and Madison in 2016, but both flipped. Modest losses increased. He lost big ground with Gadsden’s white voters as well. The Leon drop is much smaller and possibly noise; while the Duval gain was huge. At no point is their a risk the seat will turn red. However, the internal shifts show a long-time politician like Lawson is still not immune from partisan swing. More and more in the modern era, everyone is viewed as just a generic Democrat or Republican.

Looking Ahead

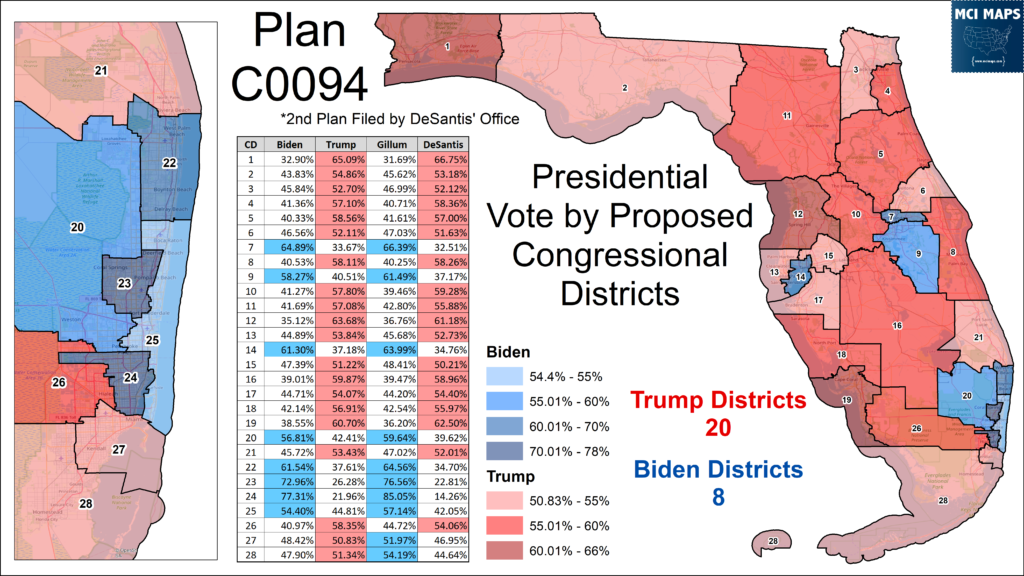

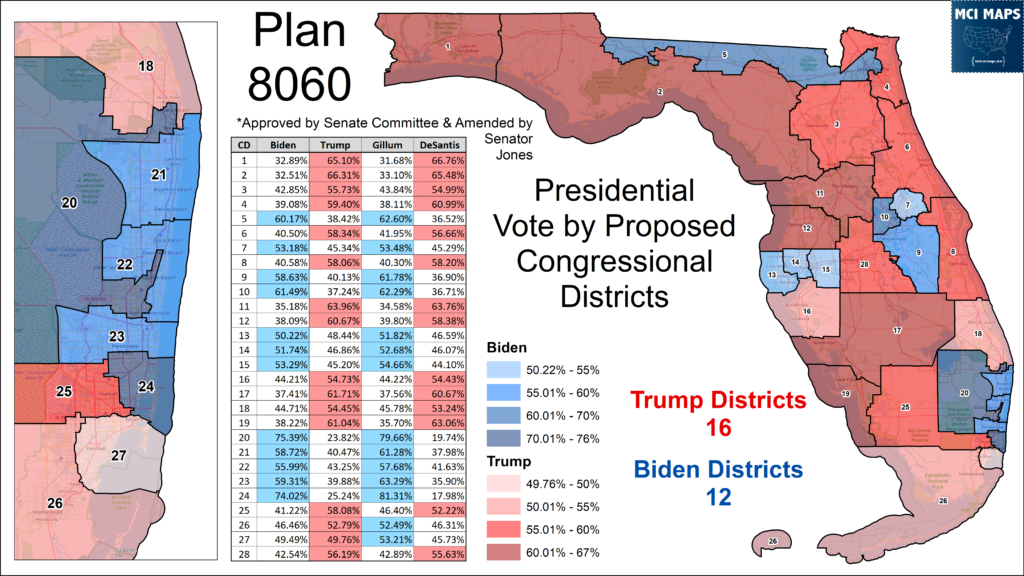

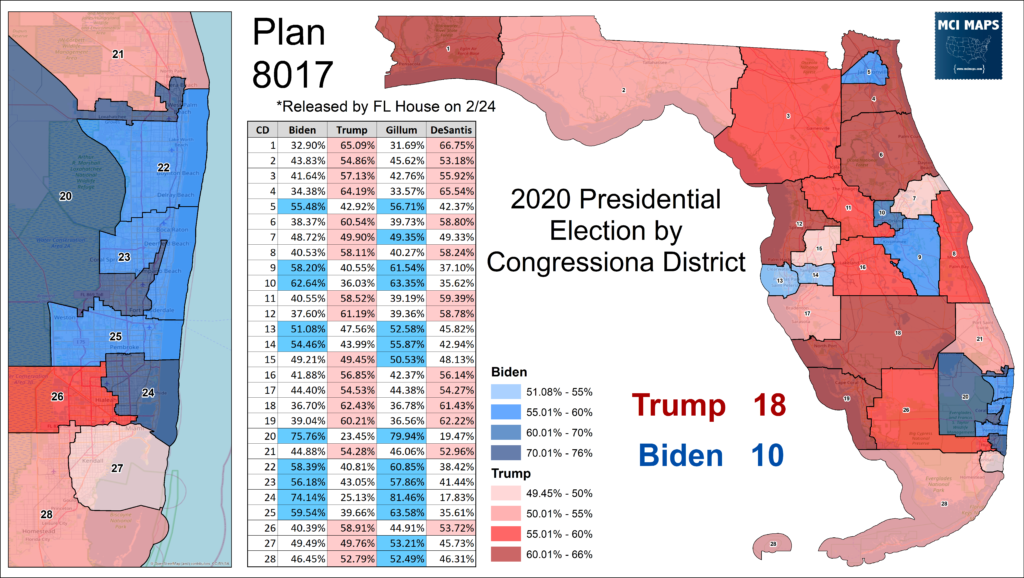

After 2020, Lawson appeared to be in prime position to continue on in the house. As redistricting got underway, it was believed the 5th district would only be subject to modest changes. Lawmakers started off viewing the 5th as a racially-protected seat that would only get modest changes. The history and reasoning for this can be read here. In that article, I go over the different racial mandates and rules governing Florida’s redistricting. However, Ron DeSantis has injected himself into the process by proposing a map of his own that destroys the 5th district as it stands.

The State Senate, meanwhile, has said the 5th will not be changed, and passed their own plan.

The State House, as of just a few days ago, offered a compromise that kept a black-access district in Duval only. Before this, they were in the same camp as the State Senate.

Go to my substack for the play-by-play of redistricting.

What map is selected should have zero to do with any specific incumbent. The argument to maintain the 5th is to preserve minority representation. However, it is no doubt obvious Lawson would want the Senate plan, or any plan with a east-west 5th district. It would be very hard for any Democrat to win in the 2nd in in DeSantis or House plans.

As I write, redistricting is not settled in Florida. I project we are heading for an impasse and a court getting involved. Lawson is in the position that many incumbents have been before, waiting to see if their district will survive the remap.

Lawson may be at the end of the road, or he may survive to fight another day. One thing is clear, he has had a remarkable electoral career