It has happened again. Another South Florida lawmaker has proposed looking to move the Florida capital out of Tallahassee. Moving the capital out of its North Florida home has been a debated and voted on topic since shortly after statehood in 1845. The capital has never budged. However, the issue has a history of getting very heated at times.

In wake of the latest push, which may or may not get much traction in the next legislative session, I have decided to look back at Florida’s capital debate. In addition, I’m going to look at the fight over Alaska’s capital – which saw three decades of referendums on the issue.

Early Florida Capitals

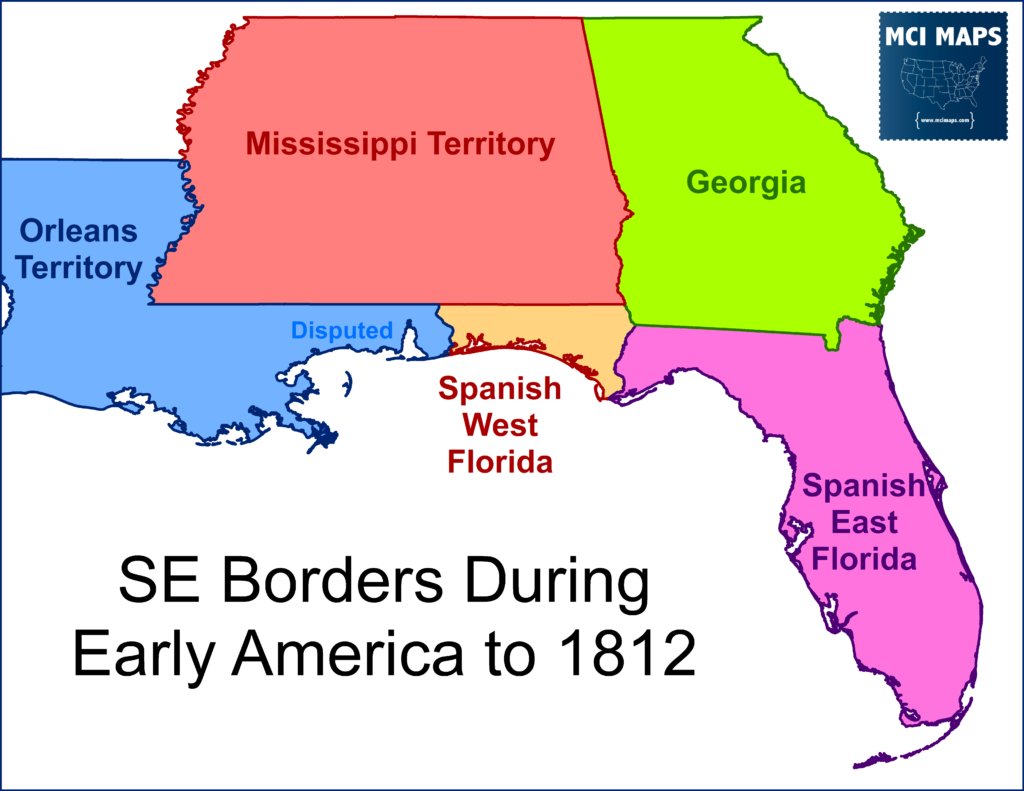

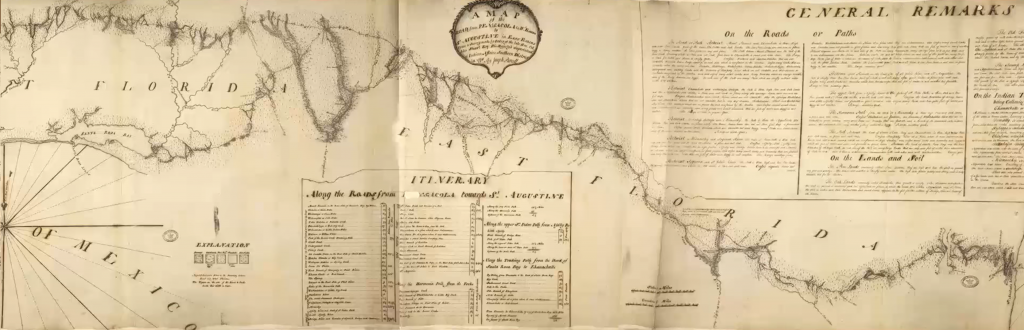

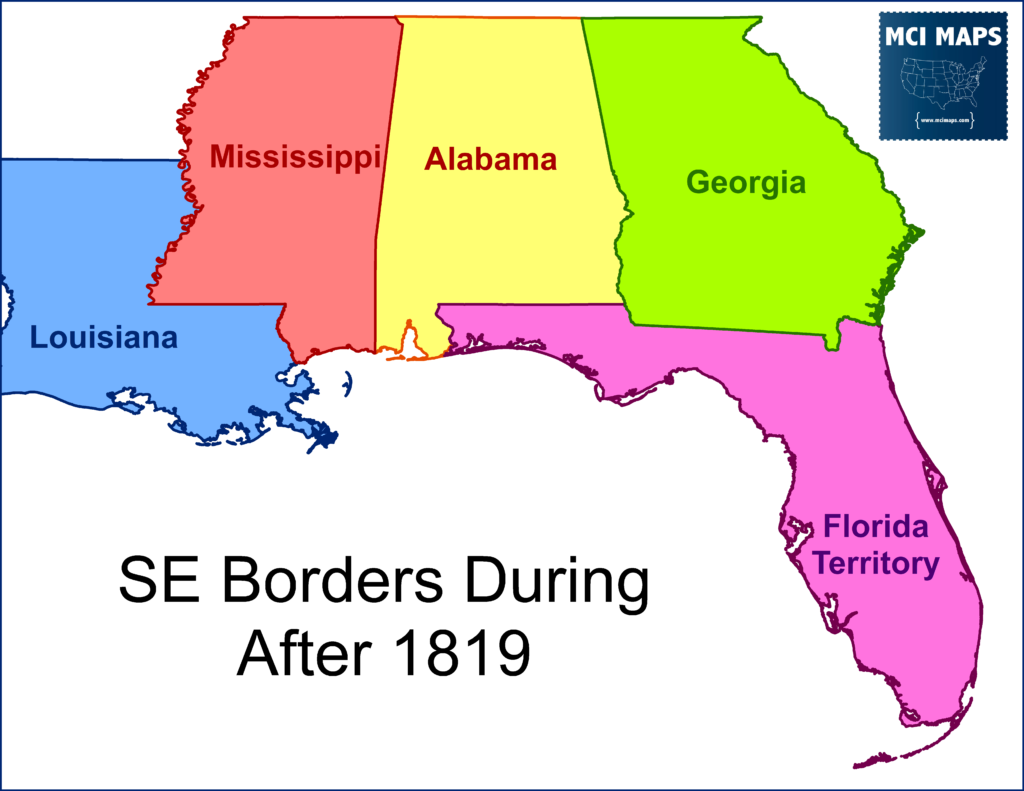

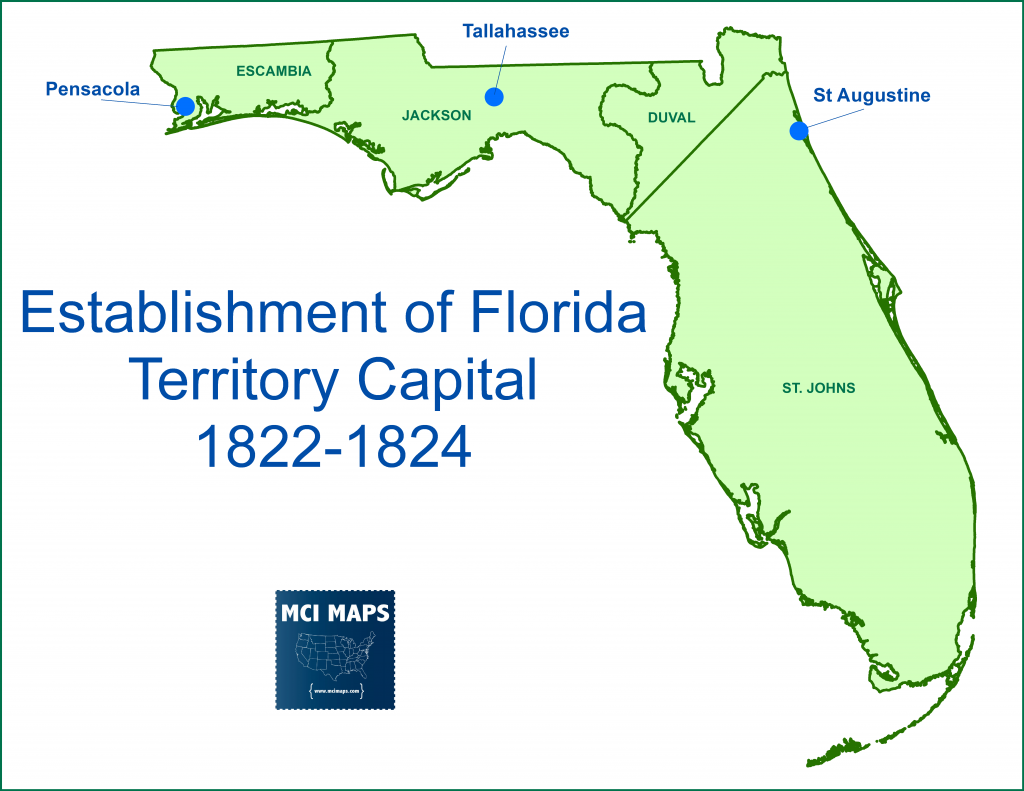

The history of Florida’s capital dates back to colonialism. What is now known as Florida was originally divided into an east and west section when it was in the control of the Spanish. The division fell on the historic Apalachicola river. East Florida’s capital was St Augustine, while West Florida’s capital was held in Pensacola.

Despite the division, the Spanish built/tracked a road to connect the two cities. The route was a mixture of trading routes, flatted roads, forest crossings, and rivers. The route was inherited by the British when they took control of the territory, and they plotted the route out. The route would go through what is modern Tallahassee/Leon County.

The Spanish bought back the territory after the American Revolution and the land was eventually ceded to the US in 1819. The two sides were united as the Florida Territory.

The first year the territorial legislature met was in 1822 in Pensacola. However, the St Augustine delegation expressed concern for the long and dangerous trek; either by ferry or land. In 1823, the government met in St Augustine, which sparked complaints from the Pensacola delegation. Then-Governor William “Pope” DuVal had two commissioners, one from each city, decide on a compromise meeting point. The commissioners picked Tallahassee, which had been a former major Native American settlement/capital. The location was higher elevation and the commissioners were captivated by the waterfall that is known today as Cascades Park.

The city’s location sat right in the middle of the two major settlements and was seen as a perfect compromise.

Proposals to Move Tallahassee

Florida became a state in 1845 after over 20 years as a territory. The state already had regional divisions; with the eastern residents feeling left out of the decision making of the counties west of the Suwanee River. The economic and political power was strongest in this region; known as “The Nucleus.” You can ready more about these issues in my article on Florida’s First Gubernatorial Election.

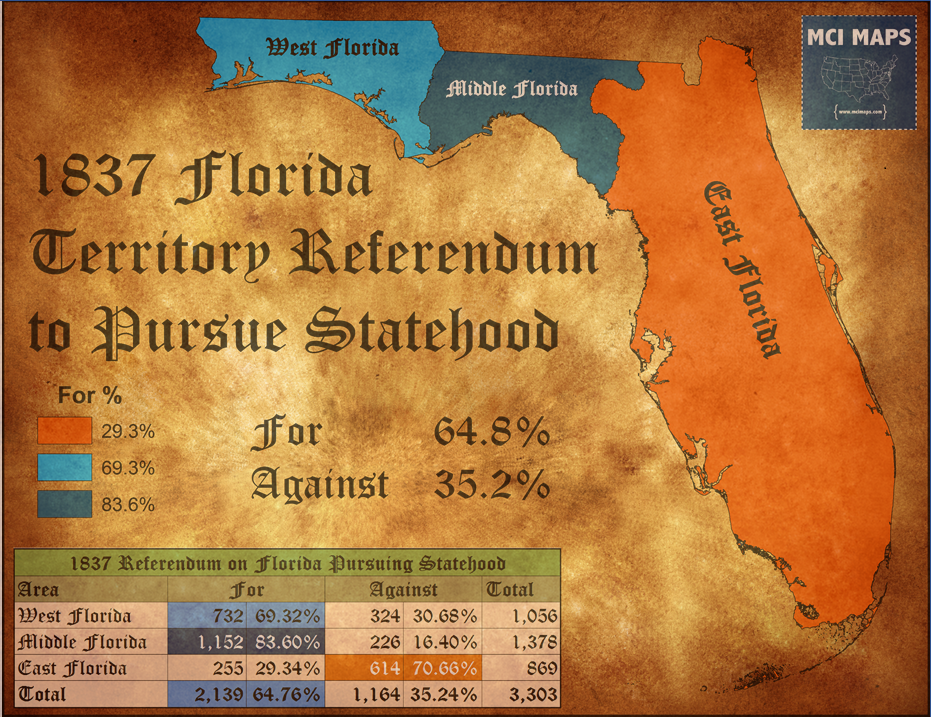

The divide in the state was so serious that the eastern counties considered breaking away to form their own territory at different intervals. In 1837, the state held a referendum on whether to pursue statehood. The measure easily passed, but was voted down by over 2-1 in East Florida.

East Florida residents still were grappling with the power imbalance in the state and didn’t want to rule out breaking off. They knew statehood would make any such break much less likely.

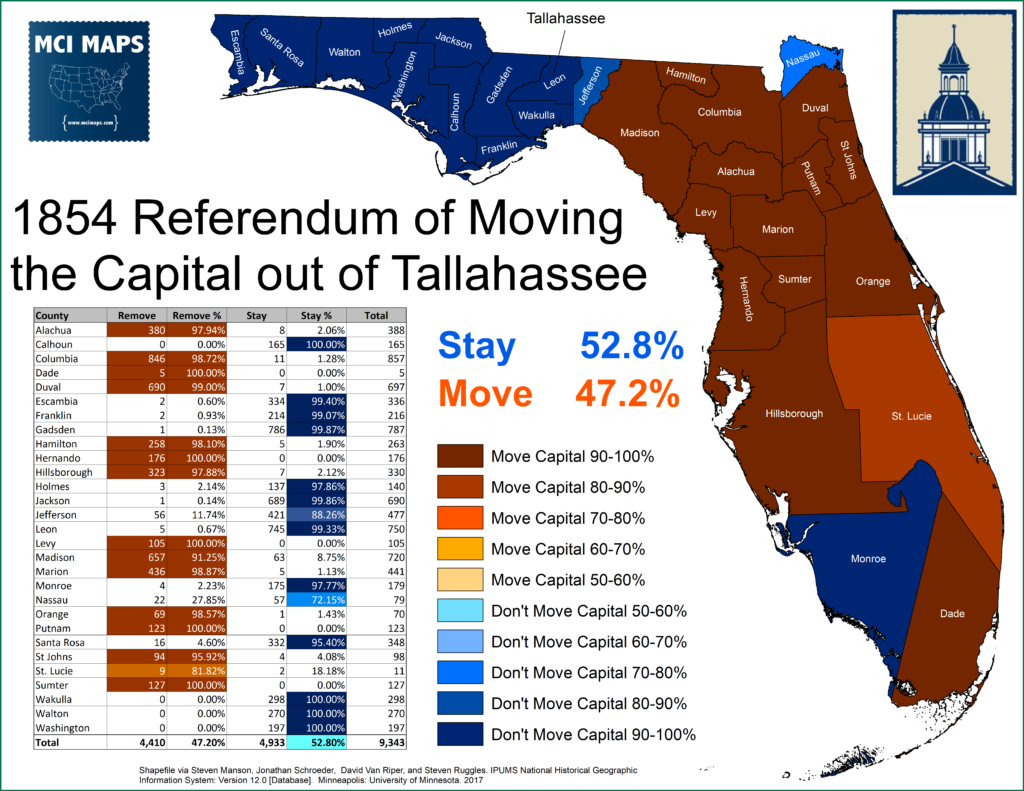

After statehood and the first couple elections, a debate about the location of the capital re-emerged. The legislature agreed a vote should be held on the issue, voting in 1853 to put a question before the voters in the 1854 midterms.

The results were 53% to remain in Tallahassee. What is striking is how all but one county were over 90% for keeping or moving the capital.

All counties from Jefferson County and West were near universal in keeping the capital where it was. The near universal opposition around Tallahassee isn’t surprising. The assumption was a new capital would move east; something voters out west didn’t want; resulting in their near universal opposition as well. East Florida, meanwhile, was near universal in support for moving the capital out of “The Nucleus.” The region was seeing population growth and its share of the vote was steadily growing – resulting in a fairly close statewide vote.

The two outlier counties are Nassau and Monroe. Nassau County’s opposition can be tied to a worry about the capital going to Jacksonville (Duval County), and gaining dominance over the region. Nassau would vote against a Jacksonville capital again in 1900.

The other outlier was Monroe County. At this time the county population was heavily based in Key West (the keys were split between Monroe and Dade at this point). Residents of Key West could use ferry and boats to traverse up to the St Marks coast (Wakulla). For them, access to Tallahassee was better than any eastern capital likely would be.

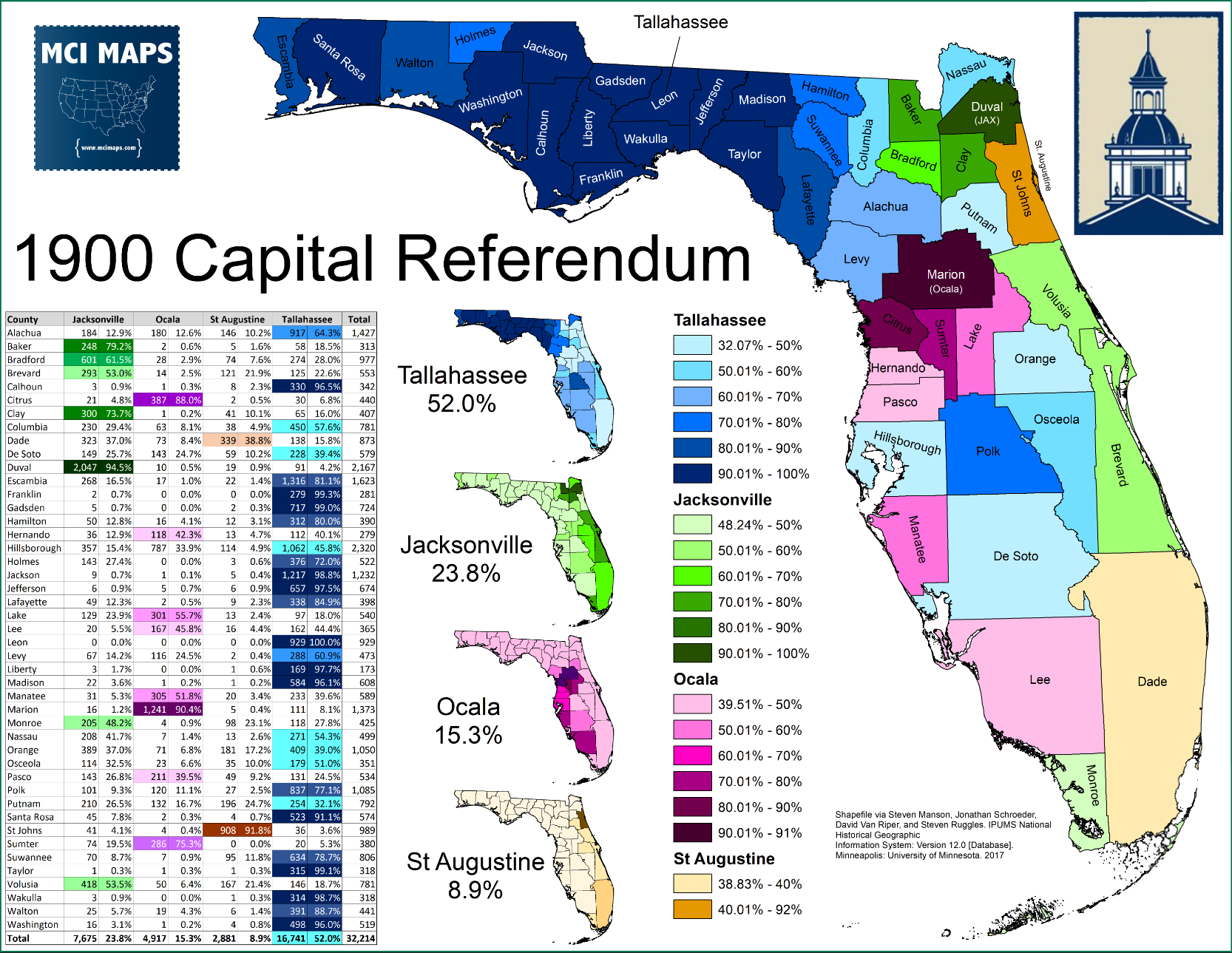

The 1900 Capital Referendum

From 1854 to 1900, there were assorted debates about moving the capital. Efforts to make moves to Jacksonville or other eastern cities all failed in the legislative process.

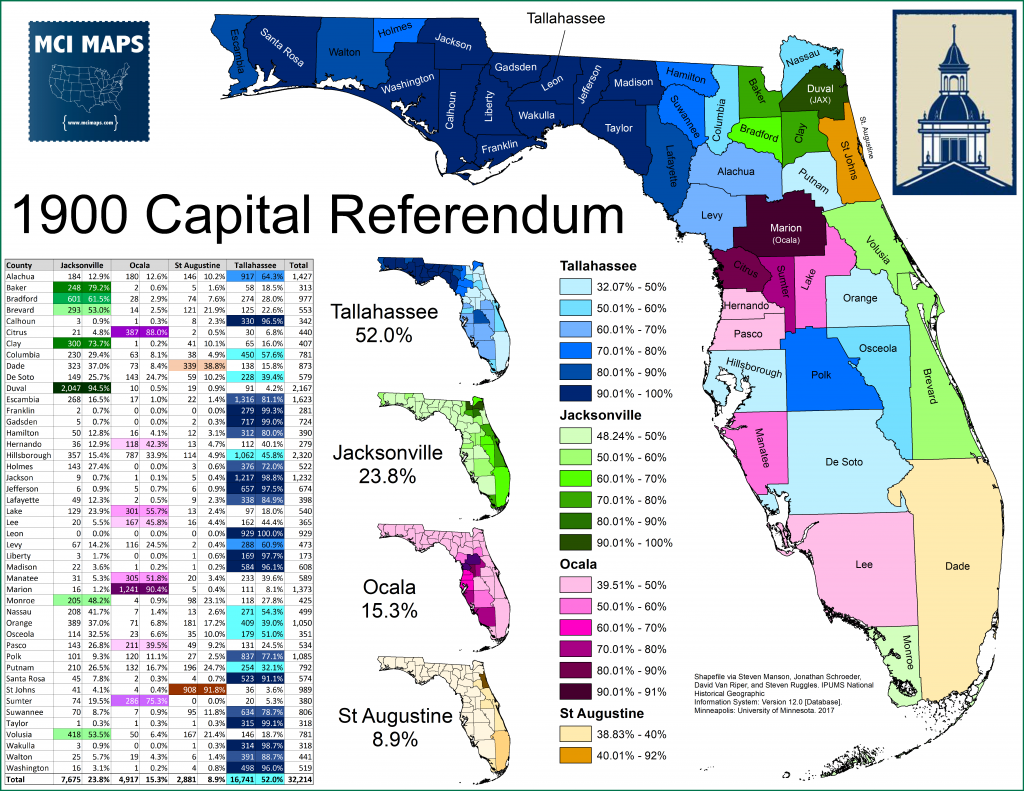

As the election of 1900 began to shape up, agitation to move the capital grew. It became clear that at the July state party Democratic convention, to be held in Jacksonville, that heavy hitters within the party, including the chairman, would push a vote on moving the capital. Jacksonville leaders were clamoring to try and bring the capital to the fast-growing city. As such, coverage of the early push focused around Jacksonville wanting the capital; not so much that other cities might get it.

At the Florida Democratic Party’s July Convention, the state executive committee set the rules for the capital question. The referendum was to be held in a Democratic primary that would take place in November, the SAME DAY as the general election for President. The capital question would only be available to white democrats. Cities that wanted to put their names on the ballot would need to make it known 50 days before the election. Cities would be listed alphabetically.

Florida’s constitution specifically lays out the capital as Tallahassee. This advisory referendum was not binding. Rather, it implored the legislature and governor to push through a constitutional amendment in the next legislative session and force another referendum on the amendment.

Tampa made it clear early into the process they had no interest. Both Ocala and Gainesville expressed interest in being on the ballot. However, in September, Gainesville withdrew from being considered. This was believed to help Jacksonville, as it would help it gather support from the surrounding counties. St Augustine made it clear they would seek a spot on the ballot, which would hurt Jacksonville’s bid to have a landslide in the Northeast.

The issue became so heated that the Escambia (Pensacola) delegation and other western counties made it clear that moving the capital further east could push them to reconsider annexation to Alabama. The annexation to Alabama issue actually pre-dated the referendum, but the issue threatened to reignite the issue. As my article shows, the Western panhandle shares many cultural traits with coastal Alabama and exists in the same time zone. Moving the capital threatened to further isolate that region of the state. The reaction from Jacksonville delegates was unhelpful – they told them to leave if they wanted.

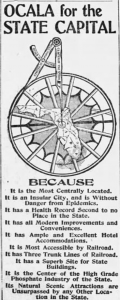

The three rivals to Tallahassee all argued in their favor. St Augustine argued that as a historic city, they were a perfect option for the east coast for those who didn’t want Jacksonville to get more influence. Jacksonville argued they already has the infrastructure and economic power to support capital costs. Ocala argued a non-coastal city was the best option and that their central location made them the best choice.

Tallahassee, meanwhile, heavily argued that the costs of moving the capital, which could top $1,000,000, would force tax increases on the population.

Newspaper coverage originally gave a projection that Jacksonville had a strong change of winning. However, as the campaign entered its closing month, it become apparent Jacksonville could very well lose. Many papers from outside the four cities advocated against moving the capital due to the cost. The ambition of Jacksonville also worked against it in the editorial pages and was used by opponents of the move.

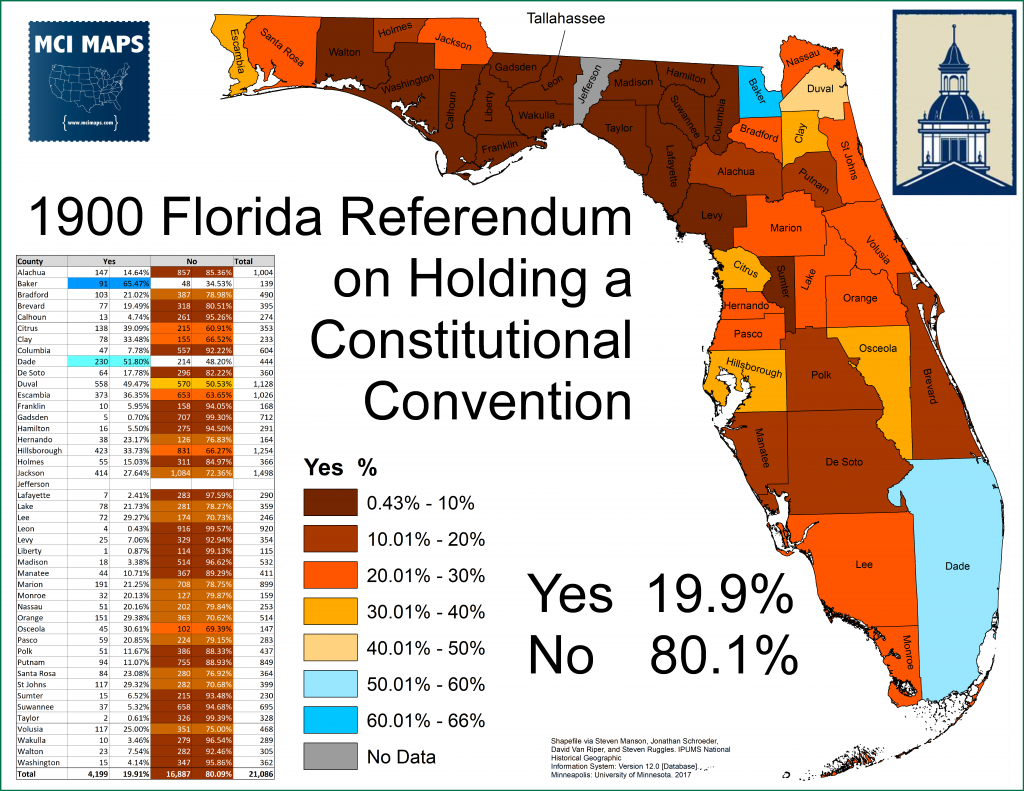

When the Democratic committee tallied the votes, it was quickly clear that Tallahassee had won. The city wound up winning over 50% of the vote. In addition to racking up 80%+ plus margins across the panhandle, the city good margins in counties not in the running for the spot. Ocala won big its home county and with its southern neighbors. Jacksonville won big in Duval and with its western neighbors, but was short circuited in St Johns and didn’t have much traction outside of the east coast. St Augustine only did strong in its home of St Johns, and pulled off a narrow win in Dade.

In addition to the vote on the state capital, a question about whether to hold a constitutional convention was put before the primary voters. Anti-moving forces saw this as a second effort to change the capital in case the first effort failed. As such, opponents of moving the capital made it clear a NO vote should take place. In addition, the proposed cost and lack of clear issues the convention would need to address caused many pro-moving folks to vote NO as well. The measure easily failed.

The measure was heavily tied to the capital referendum around the area of Tallahassee, where a NO vote closely matching Tallahassee’s vote. In other parts of the state there was much less correlation. It is notable that the vote around Jacksonville was more favorable, but the proposal even failed in Duval.

After the results of the referendums were announced, the state democratic party chair declared the issue settled. A push then began to update facilities in the city to befit a state capital. Over the next few years, money to expand the old capital building were approved and money for a governor’s mansion was passed.

Efforts to move the capital never died down, but the Tallahassee region always fought back. When complaints about the lack of paved roads to the city came up in 1913, the city passed bonds to pave the road. 1921, 1936, and 1947 expansions to the old capital building were all at least party designed to ward off complaints about the capital keeping up with a growing state. The issue became heated again in 1935, as lawmakers complained about Tallahassee still being in a radio dead zone – depriving lawmakers of entertainment.

The end result was always the same: for all the agitation to move the capital, it never got close to actually changing cities.

The 1967 Push

The last major fight over moving the capital from Tallahassee came in 1967. The debate was sparked by Miami-Dade State Senator Lee Weissenborn. The south Florida senator pushed a bill to study moving the capital to the Orlando region. In addition to his issue with the location of the capital, he was concerned about the southern conservatism of the city not matching the growing state’s south and central region. The proposal to move to Orlando was very popular with Orlando political forces.

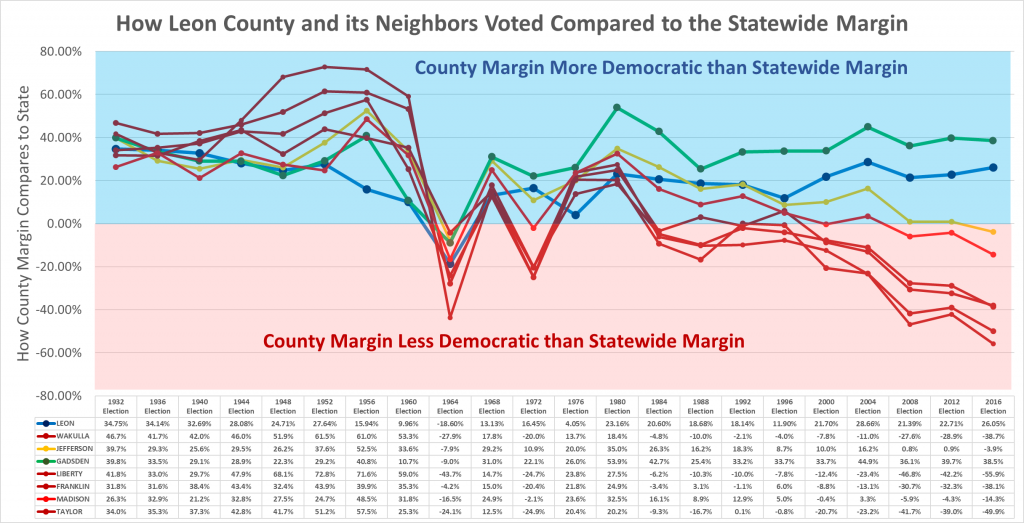

One major issue was that Tallahassee was seen as too southern to continue hosting the capital. The city had long been segregated and rocked by bus boycotts in recent history. Tallahassee had even closed its public pools years earlier to prevent integrated swimming. This was not the liberal bastion it is today. The City’s now-liberalism is heavily driven by African-Americans, students, and state employees. Back then, with state government still small, the universities still small, and a black vote just coming out of Jim Crow; the capital resembled the traditional rural southern town. The push to move the capital resulted in city voters narrowly voting to re-open the pools (no precinct data available), but city officials then delayed on actually re-opening them due to lack of money.

Right before the capital debate, Leon had voted heavily to the right of Florida by backing Barry Goldwater by a comfortable margin. It and its neighbor counties were part of the rural Democratic panhandle; but of course this is the region that began to trend more Republican after the 1960s. Leon and Gadsden (which is majority black) are the two counties in the region to become more liberal than the state overall after the civil rights debate – but that all happened well after this debate.

Race relations wasn’t the only social conservative issue for Leon. It was also alcohol.

Capital Debate Makes Leon “Wet”

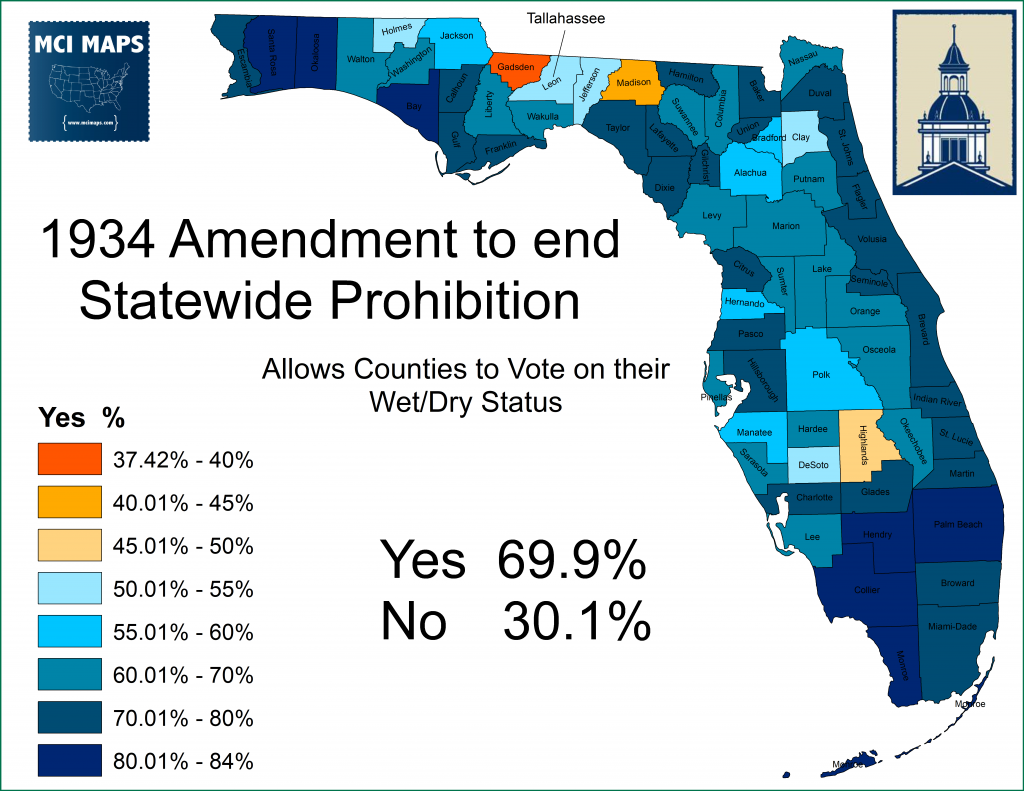

Before the 1960s, many of Florida’s panhandle counties, especially those inland, were “dry.” This overall meant no liquor could be sold, but beer was generally allowed in the entire state due to lower alcohol content. Florida voted to end state prohibition in 1934, after the 21st amendment repealed the federal ban. The referendum easily passed, with dry forces knowing they had little chance of winning the vote. The referendum legalized alcohol in the state and reverted counties to their wet/dry status from pre-1918. Counties could also vote that same day to change their status to regulate alcohol sales within their borders.

The same day that referendum took place, counties held local votes on their status if the referendum passed. The results of that was below.

Counties could also regulated if they would be just semi-wet or completely wet. Semi-wet meant allowing the sale of liquor packages at stores only. Completely wet meant allowing package sales and individual drink sales at bars or restaurants.

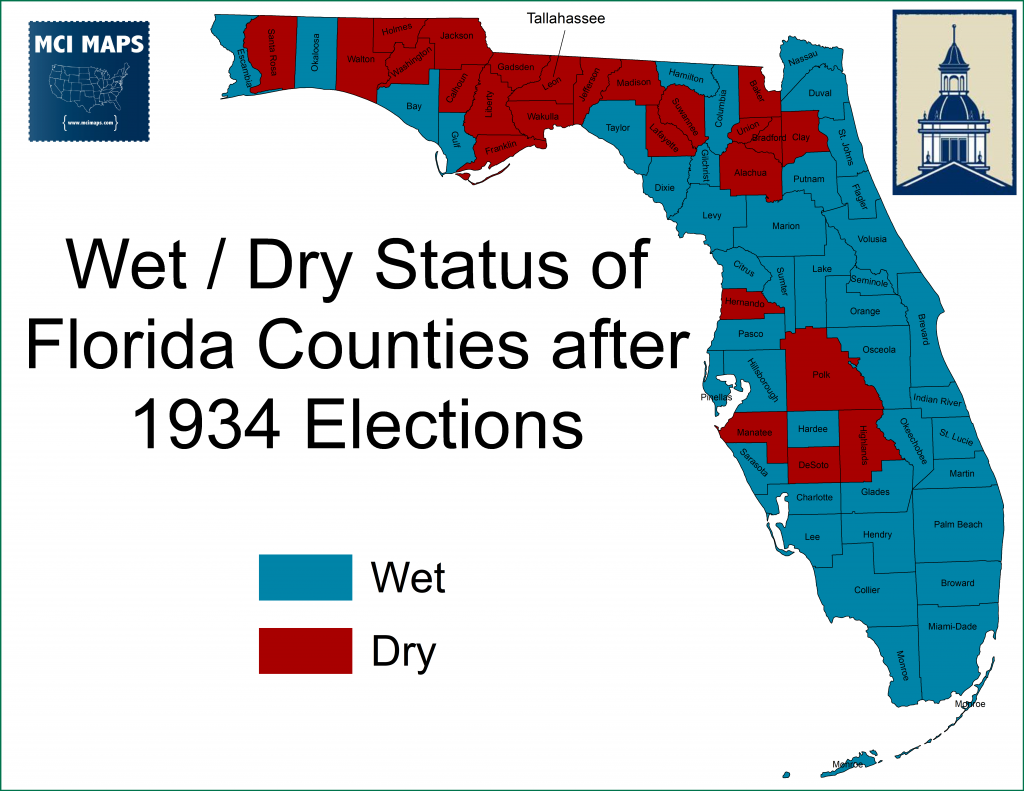

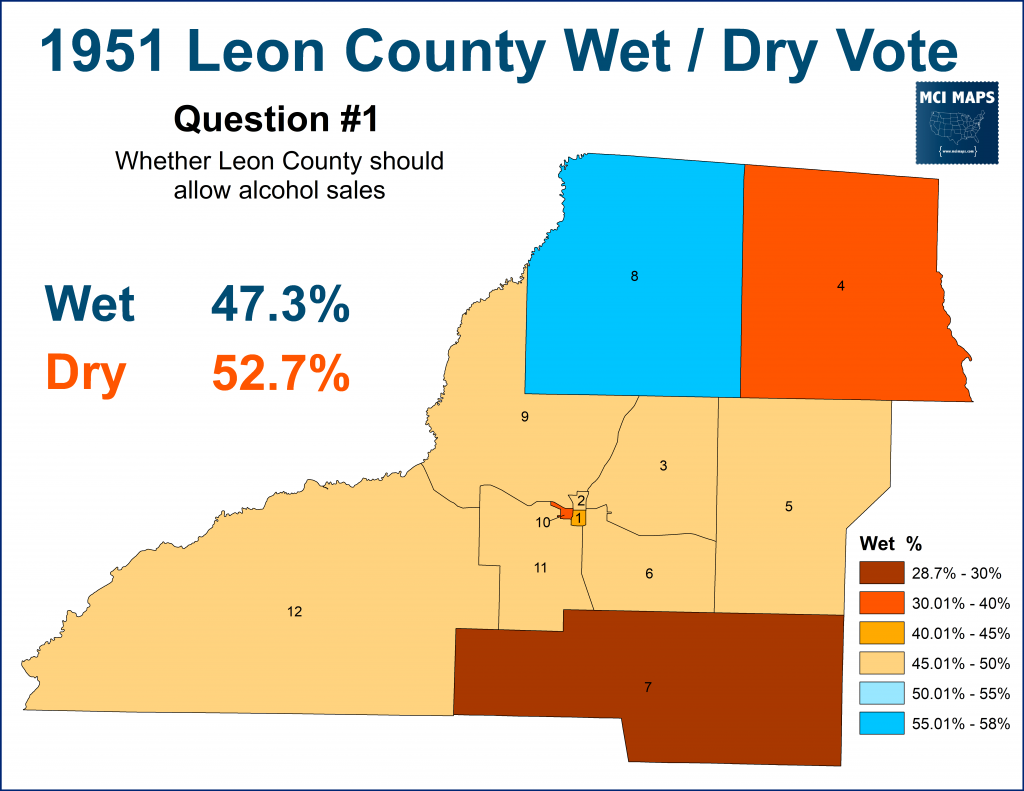

Leon was dry until 1960. A referendum to become a wet county failed in 1951; a major victory for the states’s still-formidable dry forces.

The only community to vote for alcohol was the Bradfordville area, which sat on the border with already-wet George.

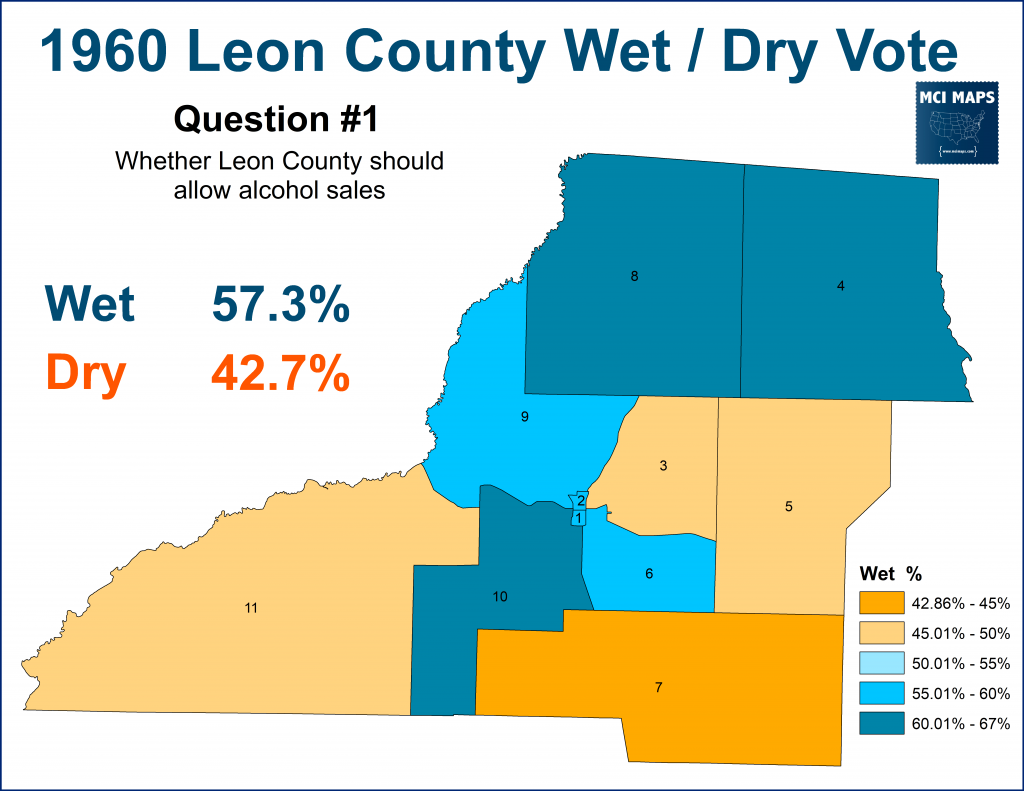

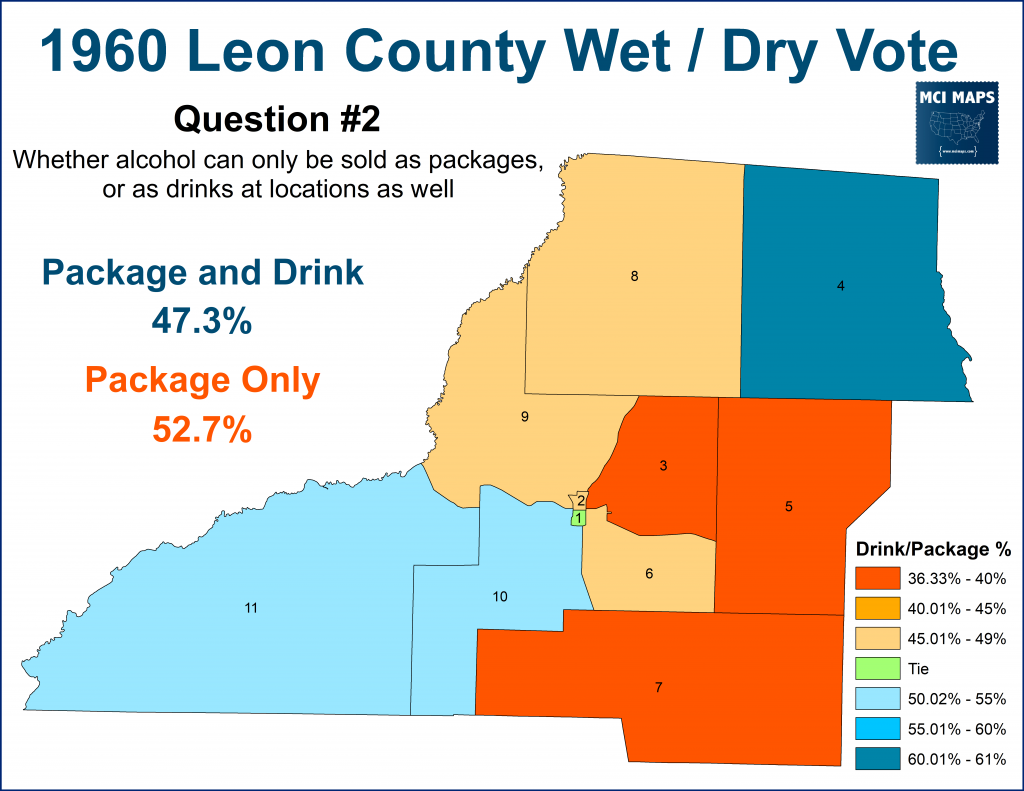

Another referendum took place in the spring of 1960. This time, forces for allowing alcohol passed, winning in the city and along the Georgia border.

However, the same day the county rejected allowing individual drinks to be sold at bars or restaurants; instead voting to only allow package sales.

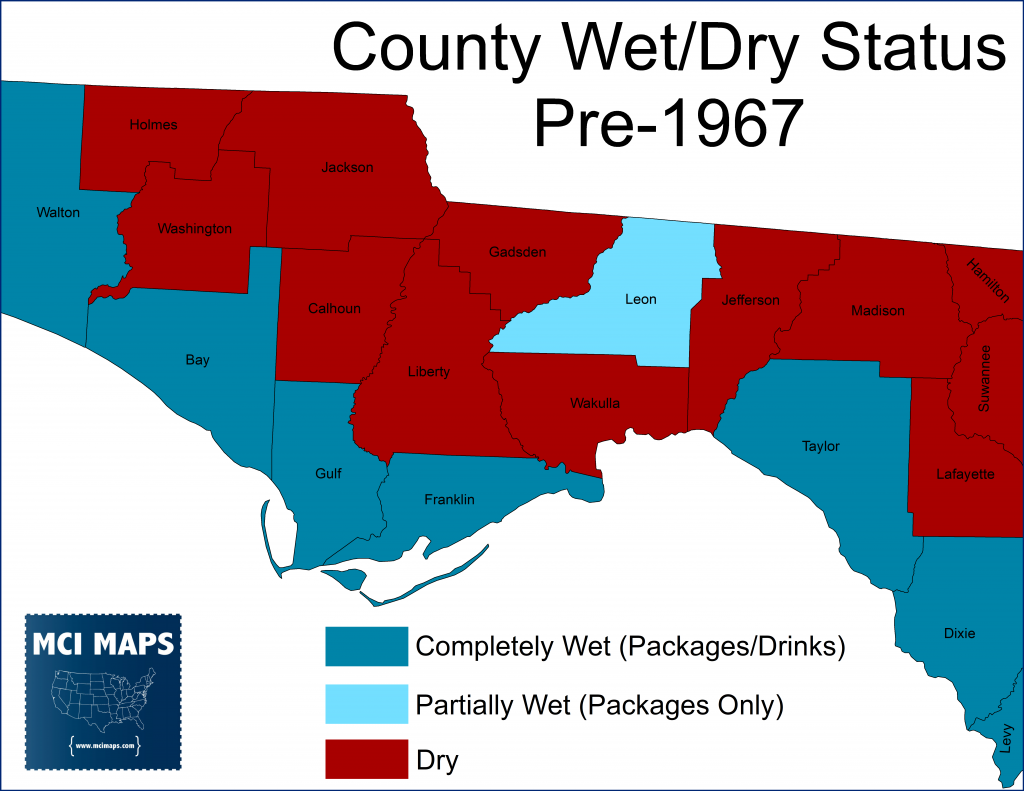

Heading into the 1967 capital debate, Leon was the only county in the panhandle that didn’t touch water that had any type of liquor sales.

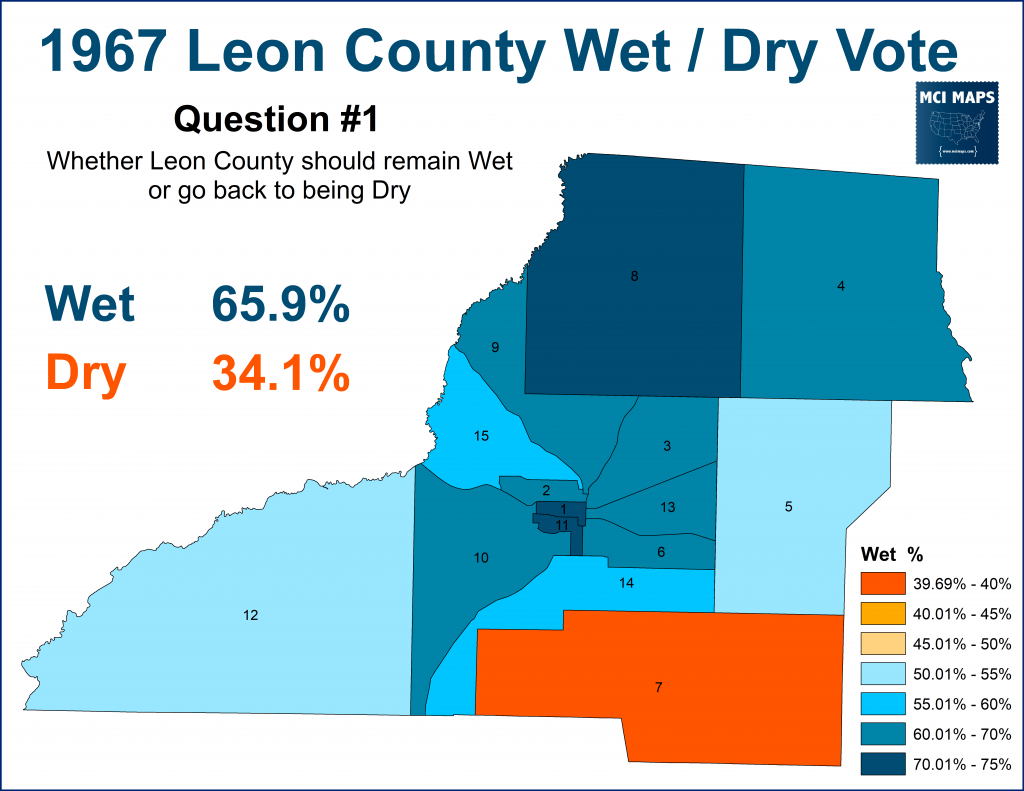

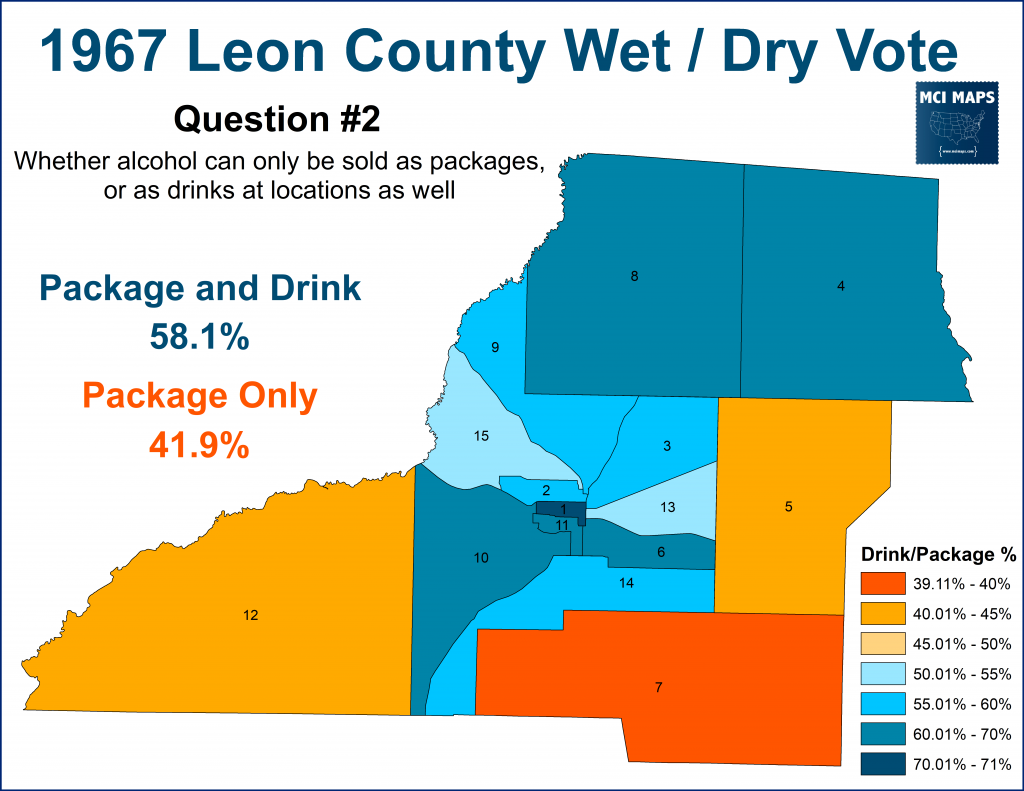

The renewed capital relocation push prompted an effort to change the drinking laws in Tallahassee. Local State Senator Mallory Horne was an advocate of a new wet/dry vote. State law required the same two-part question as before.

The 1st question, a straight up wet/dry vote, easily passed – improving on the previous margin from 1960 – only failing in the rural Woodville precinct.

The vote to legalize sales by the drink also easily passed, taking all city precincts and only losing in the rural precincts on the border.

The referendum results meant lawmakers and government officials could finally get a drink at a bar or restaurant in the city. This improvement in the night-life for the city was directly aimed at influencing lawmakers.

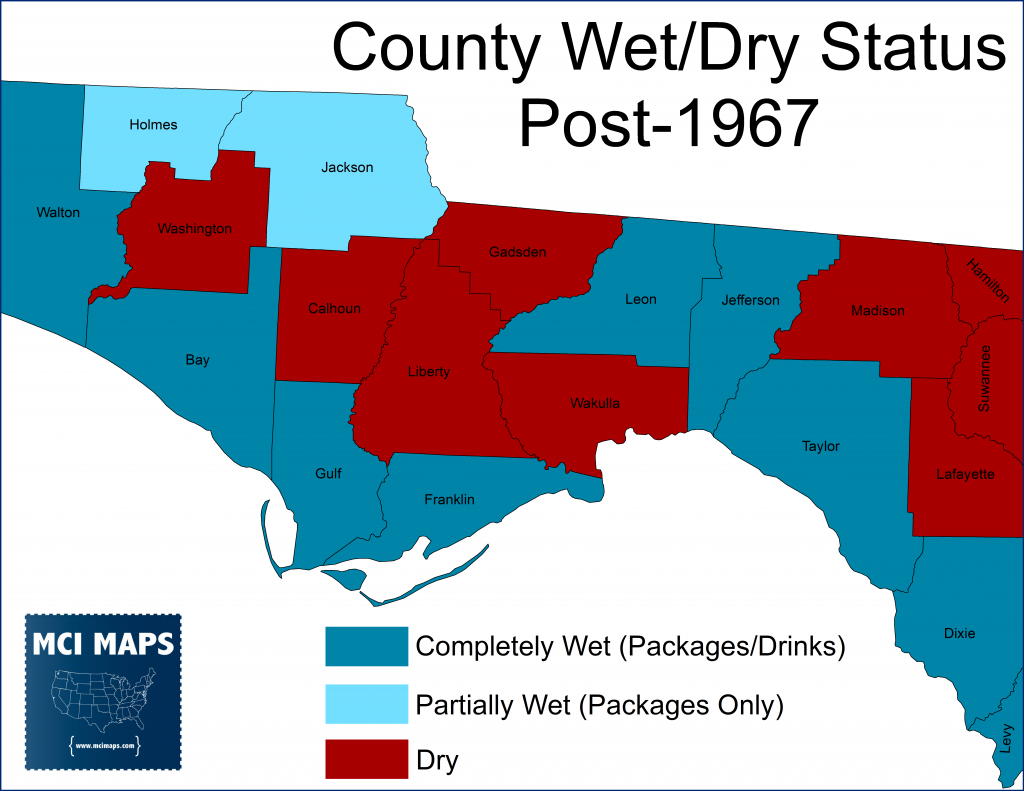

Its also worth noting several other counties held wet/dry referendums in 1967 as well in the region. Neighbor Jefferson County voted to become completely wet; Jackson and Holmes voted to allow package sales only, and Suwannee voted to stay dry.

The liberalization of alcohol laws in the capital was inevitable. but it was spurred on by the 1967 debate.

Push from 1967-1968

The push from Orlando forces and Senator Weissenborn continued through the year. However, Tallahassee had enough allies in the legislature to prevent a move. The last big effort of the session to get a bill to study the issue failed in a 30-17 vote in the State Senate.

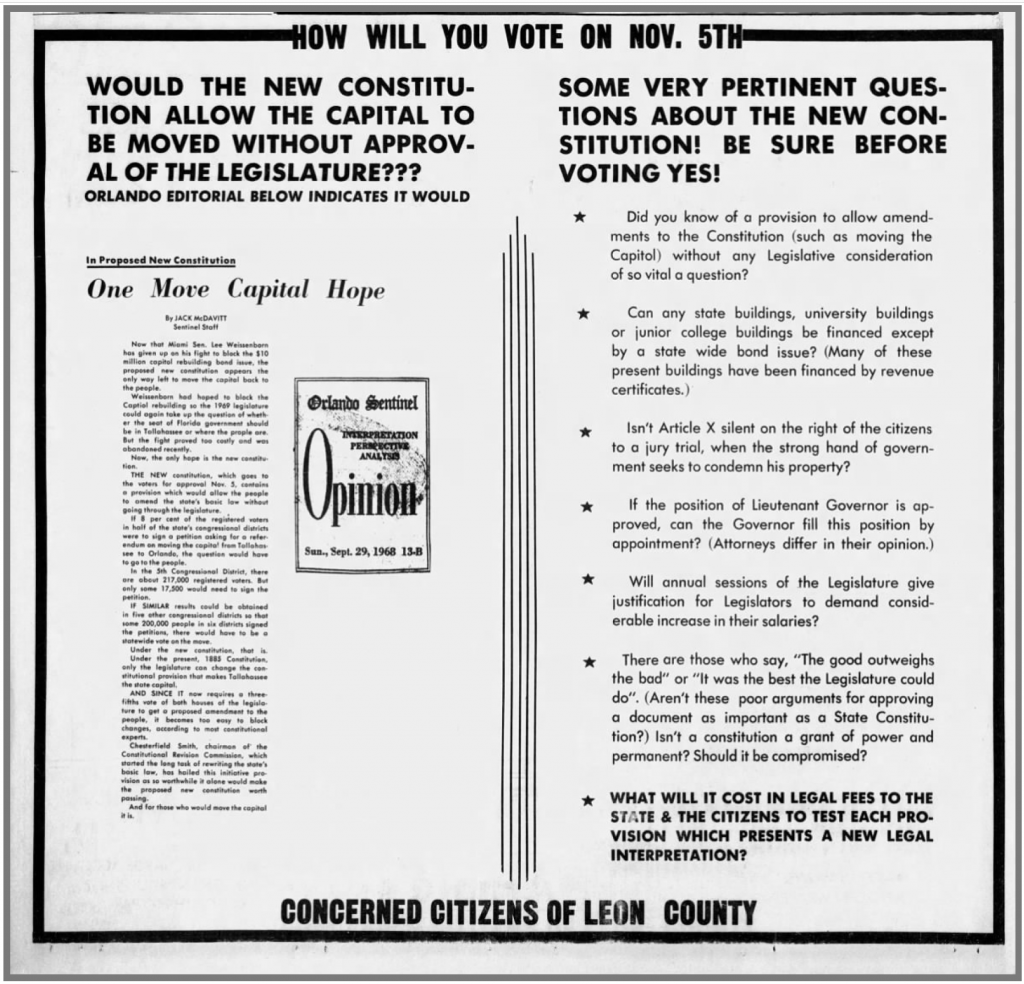

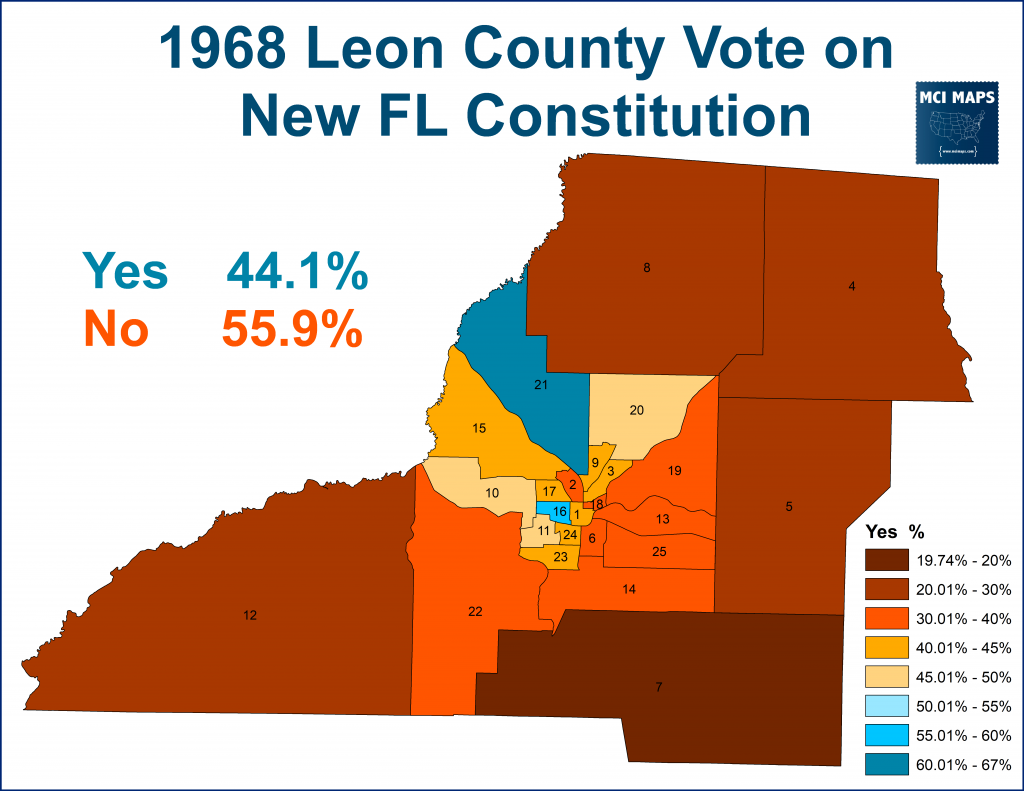

The big focus next was by pro-moving forces to keep Tallahassee out of the Florida constitution. The state was getting ready to rewrite its constitution (which would be approved in 1968) and the current document specifically listed Tallahassee as the capital. Efforts to leave the capital city undefined in the new document failed, however, and the constitution put before voters did include Tallahassee as the capital; as it does today. That means only a constitutional amendment can change the site.

Just as the constitution was being approved in 1968, and Orlando Sentinel editorial noted that the state’s new initiative process would allow citizens to try and force a vote on a new a new capital. This sparked a panic from some Tallahassee folks, and this ad even ran in the Tallahassee Democratic.

However, an editorial from the same paper also advocated a YES vote on the new constitution and told voters that voters would be unlikely to approve a move (due to the cost) even if the measure wound up on a future ballot. The fear was enough though, and the county narrowly rejected the new constitution; which passed statewide.

No statewide vote was ever successfully initiated after the new constitution went into effect. A year later, Senator Weissenborn got married and bought a house in Tallahassee (to give them a place to stay while in town on government business). The irony was not lost on locals. Weissenborn had made his push and the support wasn’t there. He didn’t attempt a new push after that.

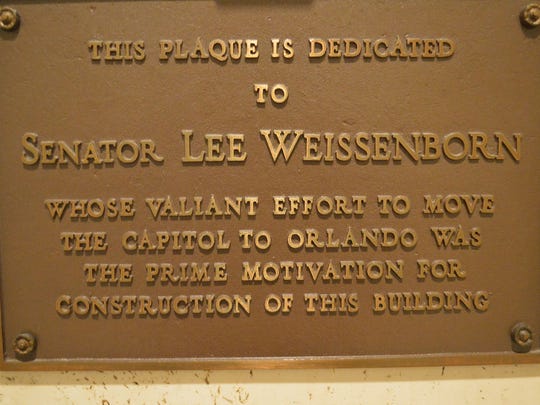

The push to move the capital sparked more discussion of upgrades to the capital buildings. The old capital had been enlarged several times. In 1972, the legislature approved money to build a brand new, towering, capital building; which was completed in 1978. The old capital was saved from demolition and turned into a Museum to old Florida.

At the new capital lies a plaque dedicated to Senator Weissenborn.

Since this debate, Tallahassee has rapidly modernized and grown thanks to an expansion of FSU, FAMU and TCC; as well as growth in state agencies. New buildings for departments and state employees dot the Leon County landscape. Tallahassee was not the small, southern town it was in the 1960s.

Florida’s capital debate has evolved over a 100+ year period, but has been fairly quiet for the last few decades. Alaska’s capital debate, which sparked 30 years of referendums on the issue, offers a cautionary tale to any effort to revitalize the debate in Florida.

Alaska’s 30 Year Capital Fight

Since Alaska has become a state, it has fought over the location of its capital. The city of Juneau was made the capital of the Alaska district in 1906, which carried over to its status as a territory and its eventual statehood in 1958. There were issues with the location, however. The main issue is that Juneau has no roads connecting it to the rest of the state. The area’s rugged landscape of mountains and waterways makes roads unrealistic. The city uses ferry’s to connect it to the rest of the state. In addition, a growing Anchorage and Fairbanks population meant the population hub was further north.

The issue came to a head in 1960 when voters hold their first referendum on moving the capital. The vote was to move to the capital to an area near the Cook Inlet-Railbelt (near Anchorage). The measure failed by 12%.

The referendum resulted in very polarized voting from the districts of the state. The area around Juneau was over 90% against the move while the Anchorage region was over 80% in favor. The referendum pitted two major hubs against eachother. Fairbanks, nervous about Anchorage gaining more influence, was against the measure, as were the more Inuit heavy northern and western districts.

Opposition to the move (or any capital move) can often be traced to a few major issues

- Concern about the cost of a move

- Concern about the rising influence of another city

- Lack of concern for ease to accessing current capital

Concern about Anchorage gaining power was a big driver for Fairbanks and Inuit voters has less concern about where the capital was. In many small, northern towns, getting to Anchorage was no easier task than Juneau.

Just two years later, pro-moving folks tried again. This time the measure mandated a move to Western Alaska, but to a site that had to be at least 30 miles away from Anchorage. The measure failed by 10%.

The voting trend was nearly identical to 1960.

The push for a new capital came before the voters 12 years after its last failure. Voters in the 1974 primary approved a new capital by a 13 point margin. The results were a stark contrast from the last two votes. While the Juneau region remained steadfast opposed, the regions outside Anchorage grew more open to the idea.

The measure narrowly passed around Fairbanks and performed much better in the Inuit-heavy North. It called for another referendum to decide a new capital, which would be held two years later.

The vote on a new capital came down to three sites, all north of Anchorage but south of Fairbanks. The choices were between Willow, Larson Lake, and Mount Yenlow. Willow easily won the vote, but even that vote saw a split between Juneau and the rest of the state.

Juneau and its surrounding districts voted for Larson Lake, the location farthest from Anchorage.

The vote between the cities followed the estimated costs. Willow was already by roads and railways and hence the least expensive site. Larson Lake would have been the 2nd most expensive, with Mount Yenlo the third.

With a new site selected, the fight over the capital was not over. Power players out of both Juneau and Fairbanks sought to stop the move by stopping funding. When a bond measure was put before the voters in 1978 for the first installment of funds, the anti-move forces pushed a ballot measure to demand the entire bill be accounted for and approved by voters. Voters approved the proposal, with the measure strongest in Juneau and Fairbanks but weakest around Anchorage and the Willow site.

The same day voters approved the above initiative, they heavily rejected a $900 million bond for the new capital.

The new requirement for a full price tag for the capital construction/move would cause a four year delay in voting.

In 1982, voters were presented with the full price tag for a new capital: $2.9 billion. The measure also made it clear that if the funds were rejected, the capital move would be cancelled.

Voters rejected the price tag by 6%.

The vote followed the same sectional divisions that occurred in the 1960s. The Juneau, Fairbanks, and Inuit north all rejected the bonds while only the regions around Anchorage/Willow supported them.

The vote revealed a major problem for proponents of moving the capital; the cost was something voters could easily balk at. An eight year period passed from the 1974 Yes vote to the bond failure. All that time, money, and energy; down the drain.

The push to move the capital didn’t end. Twelve years later, another initiative was put forward to move the capital to Wasilla, which sat North of Anchorage. Opponents quickly galvanized and not only campaigned against the proposal, but put forward a ballot measure of their own, same as 1978, mandating costs be approved before any spending took place.

The measure to move the capital to Wasilla failed by just under 10%, falling along the same sectional lines.

In addition to the Wasilla failure, the initiative that mandated approval of costs passed by 50 points. The results showed voters who even supported the move wanted to know the costs first.

This marked the end of major pushes to move the capital. A 2002 measure proposed moving the legislative session to western Alaska, but failed by a 2-1 margin. No vote has taken places since regarding moving the capital to a new city.

Conclusion

The stories out of Florida and Alaska both show major fights over capital movement that inevitably end with no change. Florida only saw a few votes to move the capital go before the voters; while Alaska had a marathon session of votes. Alaska’s story is something proponents of moving the capital in Florida should keep in mind; the cost. Voters can always get behind ideas, but when the price tag is revealed, the issue becomes a whole other matter.

The lesson also learned comes from both states: capital debates re-open and inflame deep divisions. Alaska saw very polarized voting and heated rhetoric as communities and regions fought to get the seat of power in their area. Florida saw the same divide in its referendums but also in legislative battles. That division will arise again if the issue is heavy debated. The question for proponents is, is it worth it?

Of course, any effort to move the Florida capital is a long way off. Efforts to study the issue are the current item; and even those probably won’t go far. Any actual vote would require a constitutional amendment. Thanks to a change in Florida law in 2006, any constitutional amendment require 60% of voter approval; making chances of passage even less likely.