Hendry County is often forgotten in Florida residents. With a population of just 40,000 people and dominated by farmland, its one of the many “drive through” counties of the state. Its political importance comes from its role as one of several counties with large sugarcane production: a staple crop of Florida. However, even the most obsessed Florida politicos give little though to Hendry’s internal politics. This article, however, is going to delve into Hendry County in much more detail. Why? Because Hendry County, which operates under single-member districts for its county commission, is considering moving to at-large elections. To outside observes this may not seem like a big deal. However, there are serious racial concerns in this proposal. This article will delve into Hendry’s demographics, politics, and ultimately its districts as I aim to show Hendry’s changing of how it elects its council could run afoul of the Voting Rights Act.

Hendry’s Unique Demographics

Hendy’s Migrant Farm Workers

In the US Census, Hendry County stands out as one of Florida’s second most Hispanic County (52%) – right behind Miami-Dade. However, Hendry County’s demographic profile doesn’t tell the complete story when it comes to electoral power. Hendry is so heavily Hispanic due to its large share of migrant farm workers who work in the sugarcane fields of the region. The county is home to over 80 migrant worker camps. Many workers stay all year while others come in seasonally. Most come on work visas. These workers are counted in the census and the camps are regulated by the state. The migrant camps vary by size and living arrangements, but one common theme is the large number considered below state standards. Camps with multiple violations are a frequent occurrence, but workers often have few options and the state’s punishment system is shockingly weak. Hendry County ranked highest in camps getting an “unsatisfactory rating.” Workers in these camps, often here to make money to send back home, are very vulnerable to landlords and employers. A major news investigation revealed women migrants are dangerously susceptible to rape. Hendry’s migrant population and their conditions are more under the purview of the state than county. However, camps and workers still fall under the purview of the county. The large migrant population, which is a major economic engine in the region, also means US Sugar, the largest employer in the county, has a strong role in county politics.

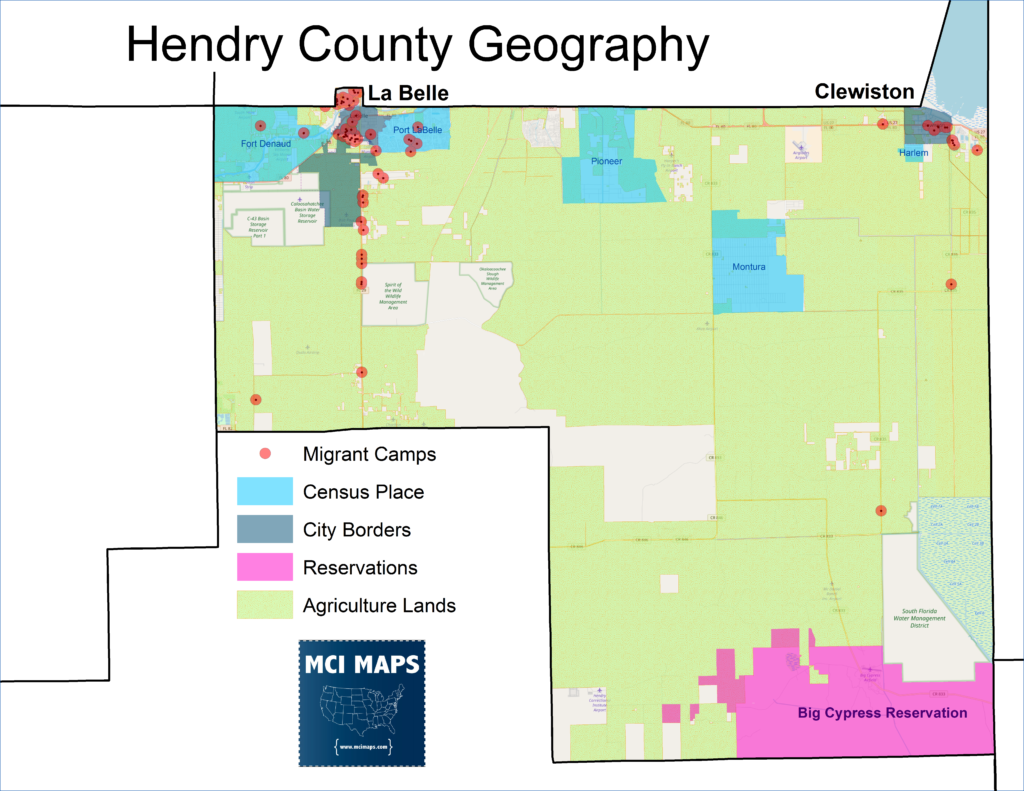

Key Geographic Points

The map below gives an general layout of Hendry County’s geography. The two cities: La Belle and Clewiston, are separated by a state road that marks the northern border of the county. It is roughly a 30 mile drive from one city to the other. Other census-designated communities are also highlighted. Most of the county is farm land and the Native American Reservation in the south. Migrant camps dot the landscape.

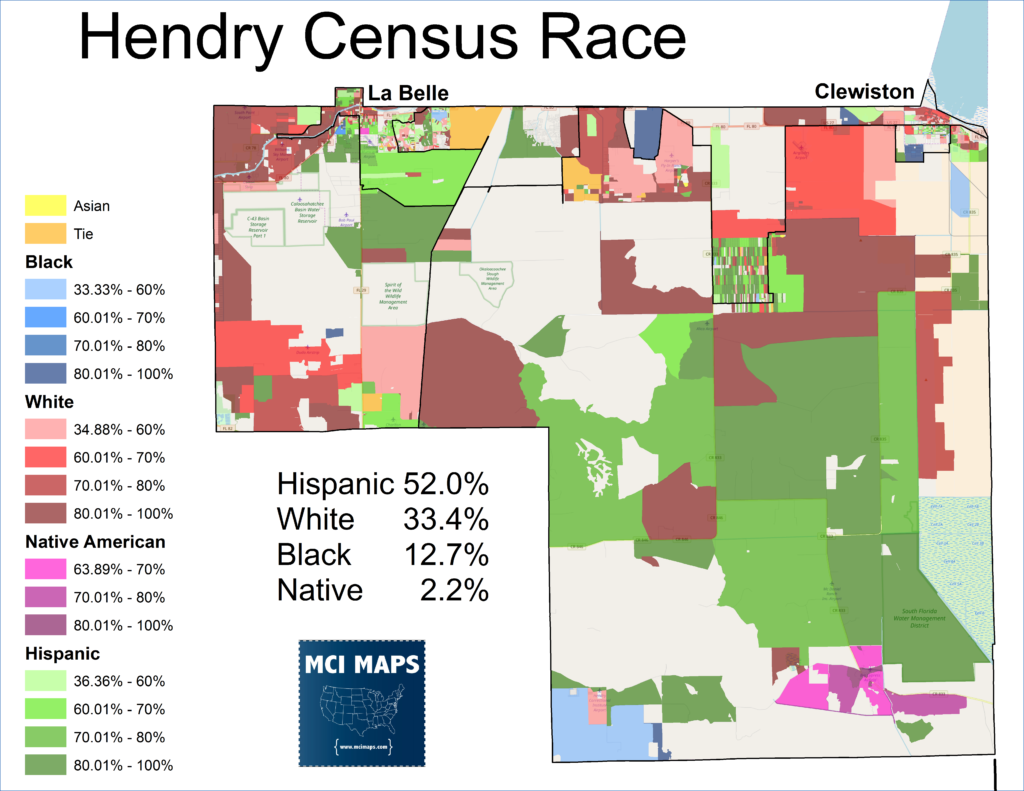

The census block map below is color-coded by race. Much of the county doesn’t even have populated census blocks. Even then, several large/rural blocks have very few people inside them.

The empty census blocks are largely agriculture fields; which also overlap with several of the large-but-low-populated blocks in the middle of the county.

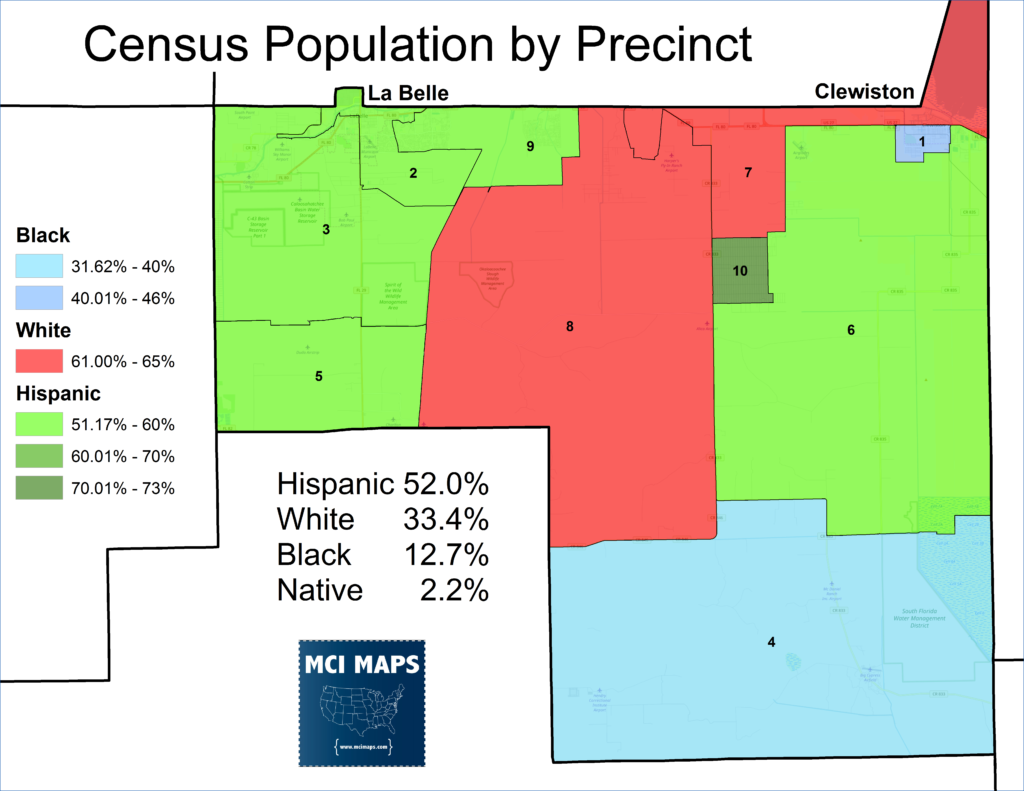

To look at the racial makeup another way – the map below color-codes the county’s precincts based on race (via the census). Most precincts are majority Hispanic and only two are white.

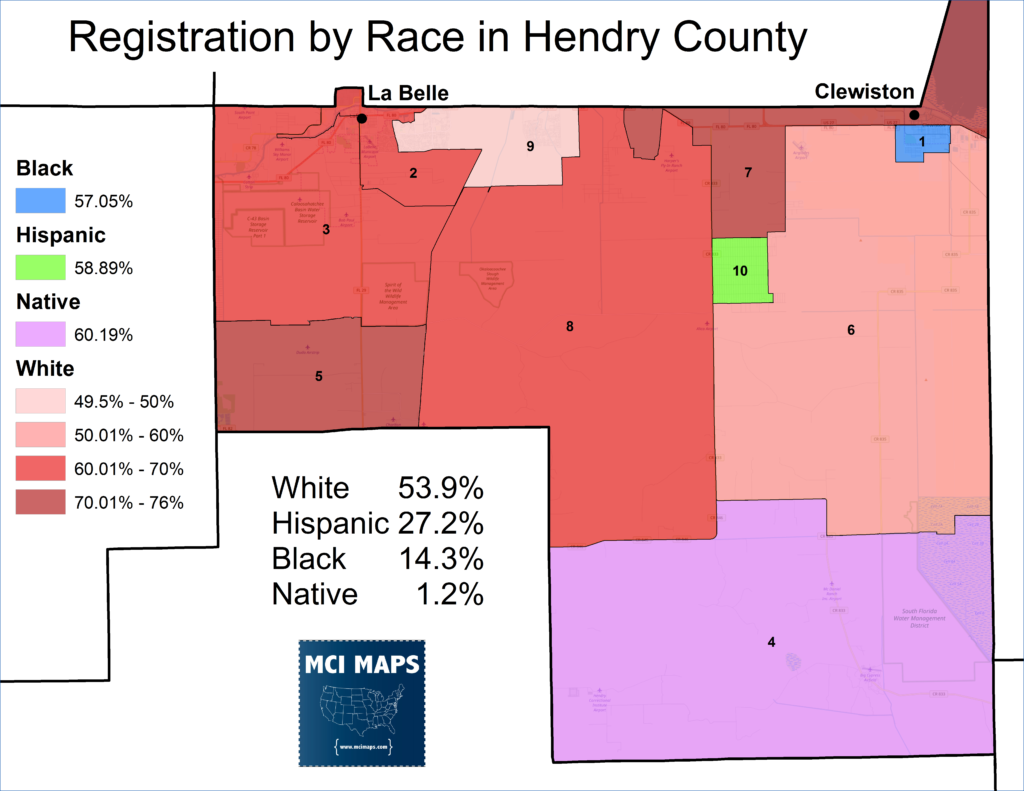

However, as I mentioned before, Hendry’s racial makeup is skewed by the farm workers. When we look at the demographics by voter registration, it paints a very different picture.

White voters are a solid majority in the county. Hispanic’s only have a majority in the Montura precinct; African-Americans dominate in the Harlem precinct, and Native Americans’ have the reservation precinct. Every other precinct is white majority or plurality.

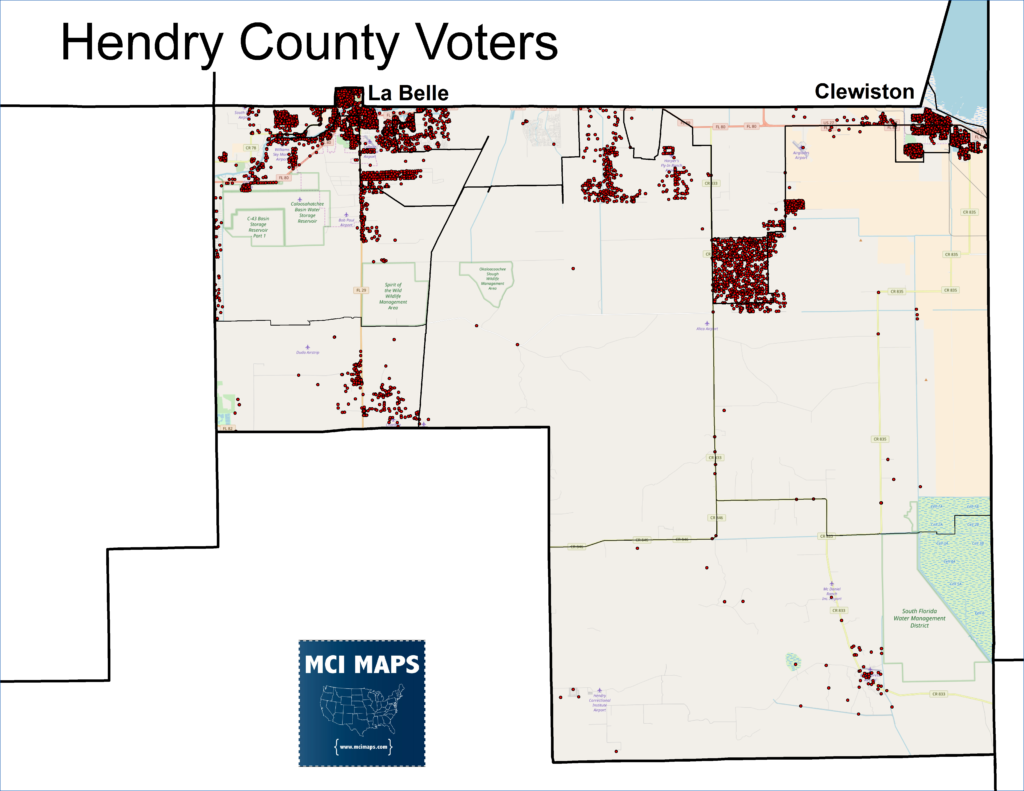

The precinct maps are a nice and smooth way to show the demographic but they do give a misconception about where Hendry’s voters are. Hendry’s population clustering can be best visualized by looking at the county’s registered voters geo-coded by address. The resulting map shows populations heavily concentrated in La Belle, Clewiston and the different census-designated (but not incorporated) communities, especially Montura.

Hendry’s Politics

Hendry’s political leanings are similar to other rural counties in Florida. The county used to be solidly Democratic at the local level but more Republican in national and federal races. Like its rural counterparts, the county has moved more to the right locally in recent years. However, unlike some of its rural counterparts, the county’s larger non-white population keeps it from becoming a deep-red county.

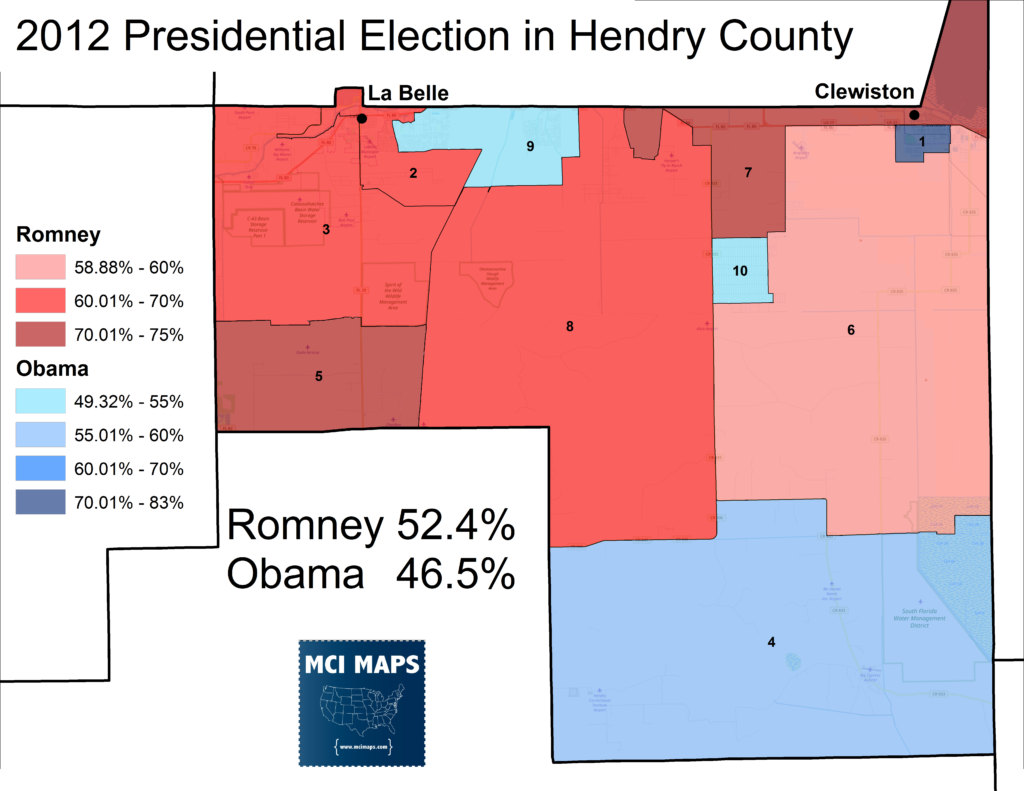

In 2012, the county gave Romney a modest win, with Obama take the the less-white precincts while losing the others by solid, but not blowout margins.

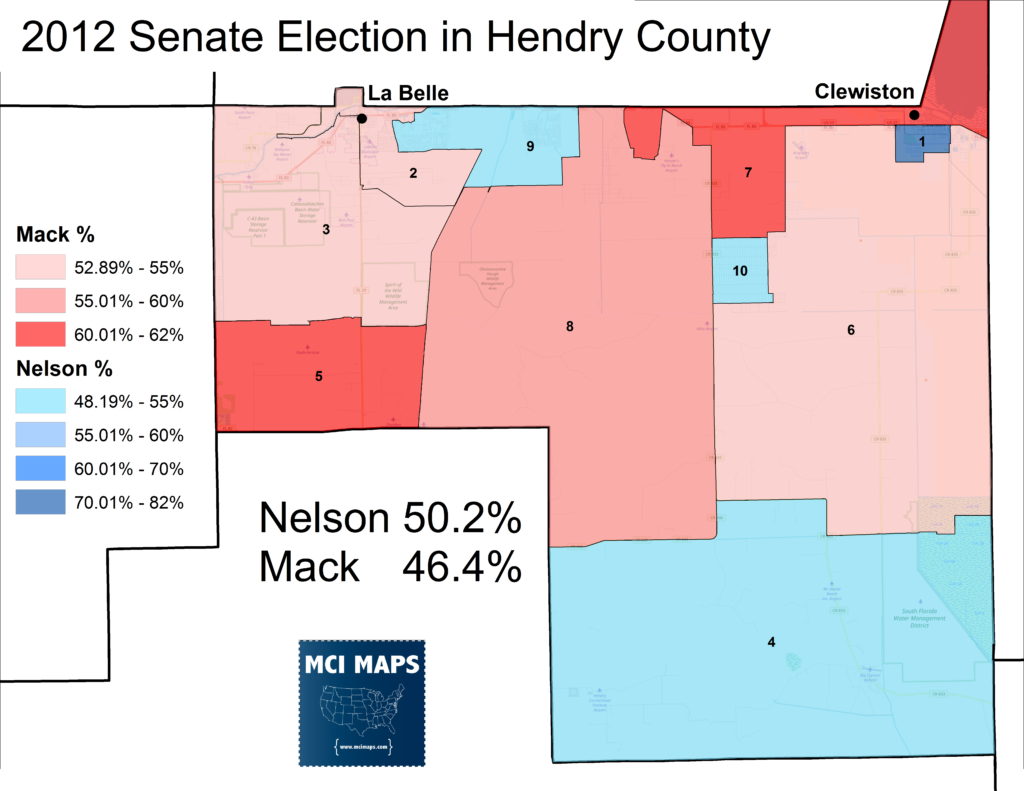

That same day, Senator Bill Nelson won the county while winning the same precincts; but getting better margins elsewhere.

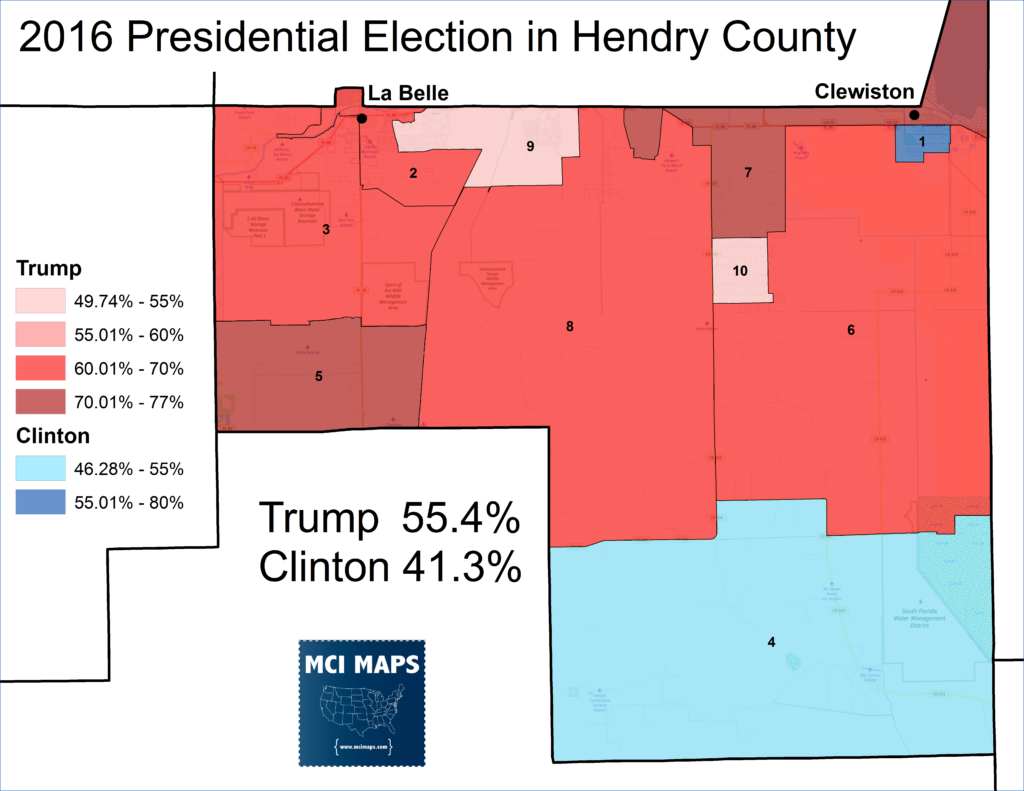

Then in 2016, Trump improved on Romney in the county, winning by double digits and winning two precincts that had backed Obama.

Montura’s precinct, which is majority Hispanic, is not heavily Democratic and has backed Republicans. This could be due to its white population coupled with modest Democratic margins with the Hispanics; or Hispanics voting for both parties. The county’s Hispanics that are citizens has a modest Cuban share, which could explain the more swingish nature of the Hispanic population compared to other parts of the state.

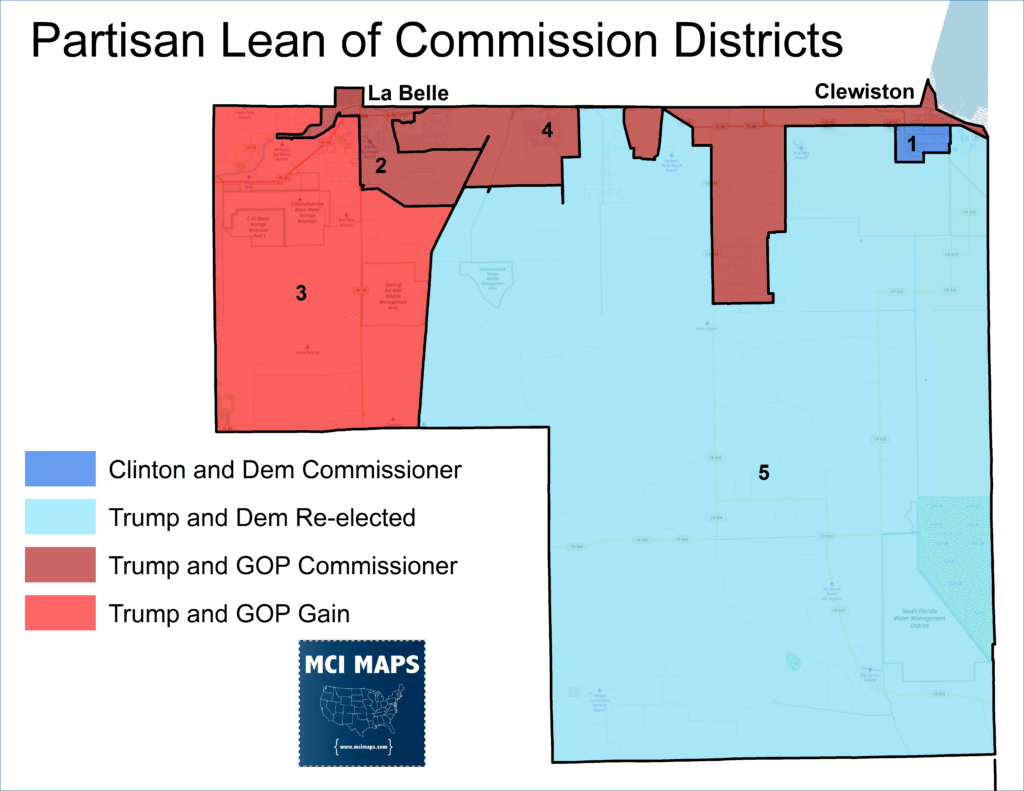

The county is normally reliably red for statewide races; with Nelson being the most recent Democratic winner. However, the county boasts 2 Democratic commissioners, a Democratic Clerk of Court, Supervisor of Elections, Tax Collector, and Property Appraiser.

Hendry had 3 Democratic commissioners before the 2016 elections but the 3rd flipped to the GOP (after the Dem flipped it in 2012). Clinton only won the 1st district; which a majority African-American seat. Trump won the rest.

Local Democrats outperform the national party repeatedly. Even in losing, the County 3 commissioner did better than Clinton. Meanwhile, the County 5 Democratic commissioner fended off a GOP challenge while Trump won his seat.

Racially Polarized Voting for Sheriff

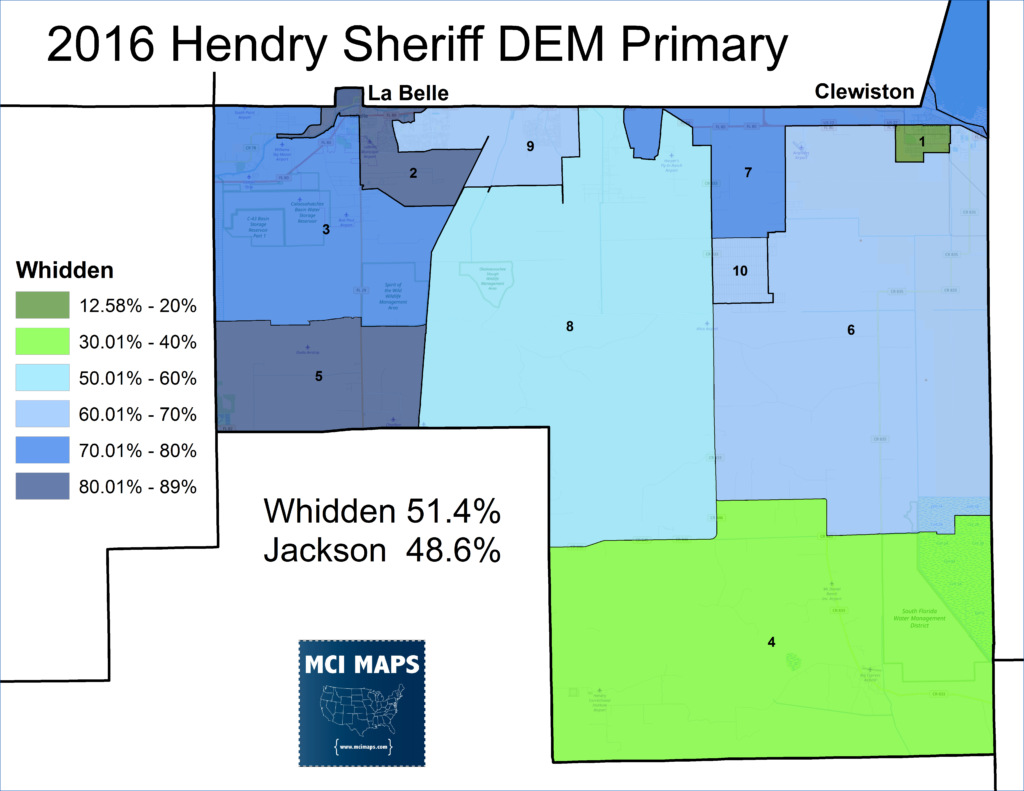

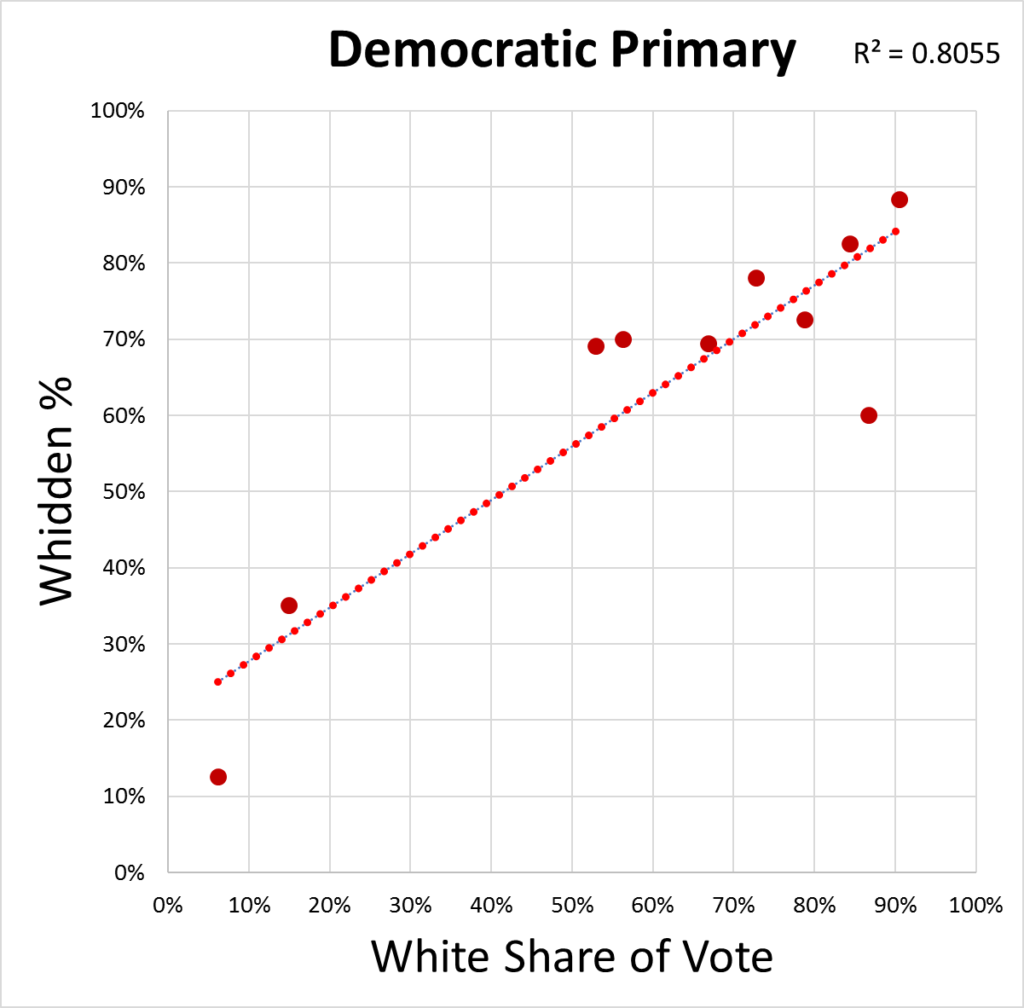

Hendry’s Sheriff was also a Democrat until early into 2017. Sheriff Steve Whidden, a conservative Democrat, switched to the Republican Party shortly after his re-election. Whidden was long believed to only be a Democrat because at the time of his election, in 2008, Democrats were still the strongest party locally. Whidden backed Rick Scott’s re-election in 2014. He nearly lost the Democratic primary in 2016. He was challenged by an African-American former deputy with the Palm Beach Sheriff’s office; Johnny Jackson. Jackson only won two precincts but that was enough to nearly overtake Whidden.

The Democratic primary in that race was 47% white, 39% African-American, and 10% Hispanic. Jackson’s raw vote margin in Precinct 1 (86% African-American in primary) was so high it took 8 precincts to narrow the gap. The raw vote margin in Precinct 4 was very small due to low Native American turnout. It should also be noted that the Montura (Hispanic) precinct was more white than Hispanic in the primary due to Hispanics being registered independent in larger numbers and thus shut out of the primary.

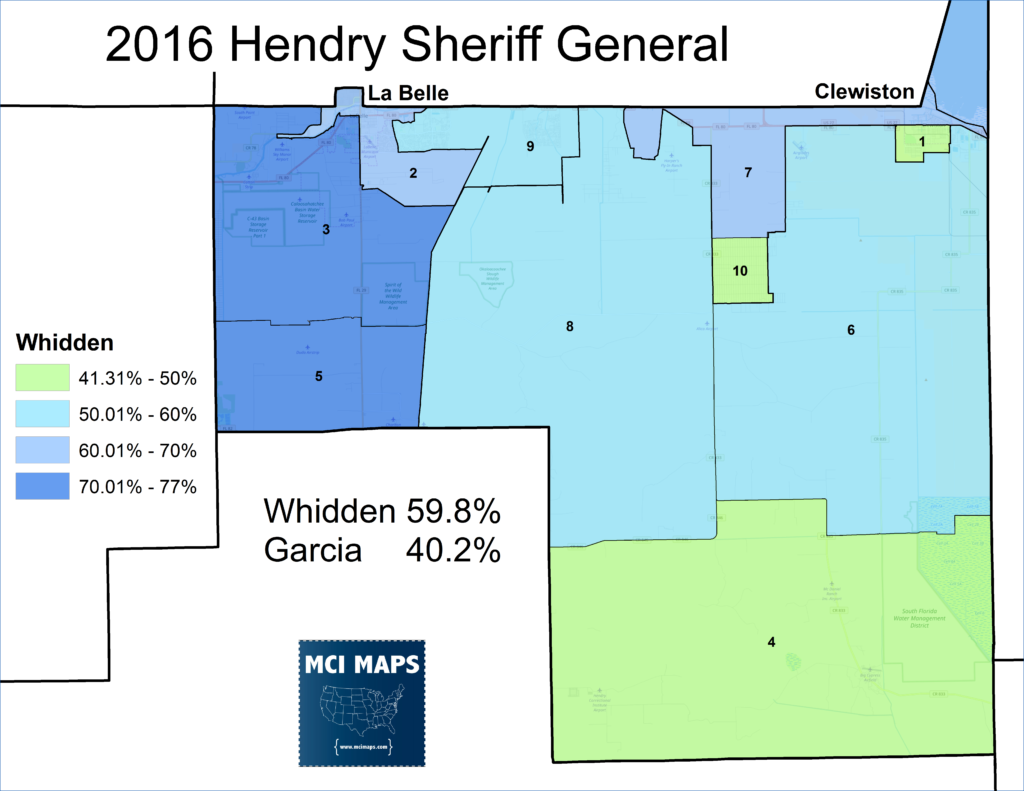

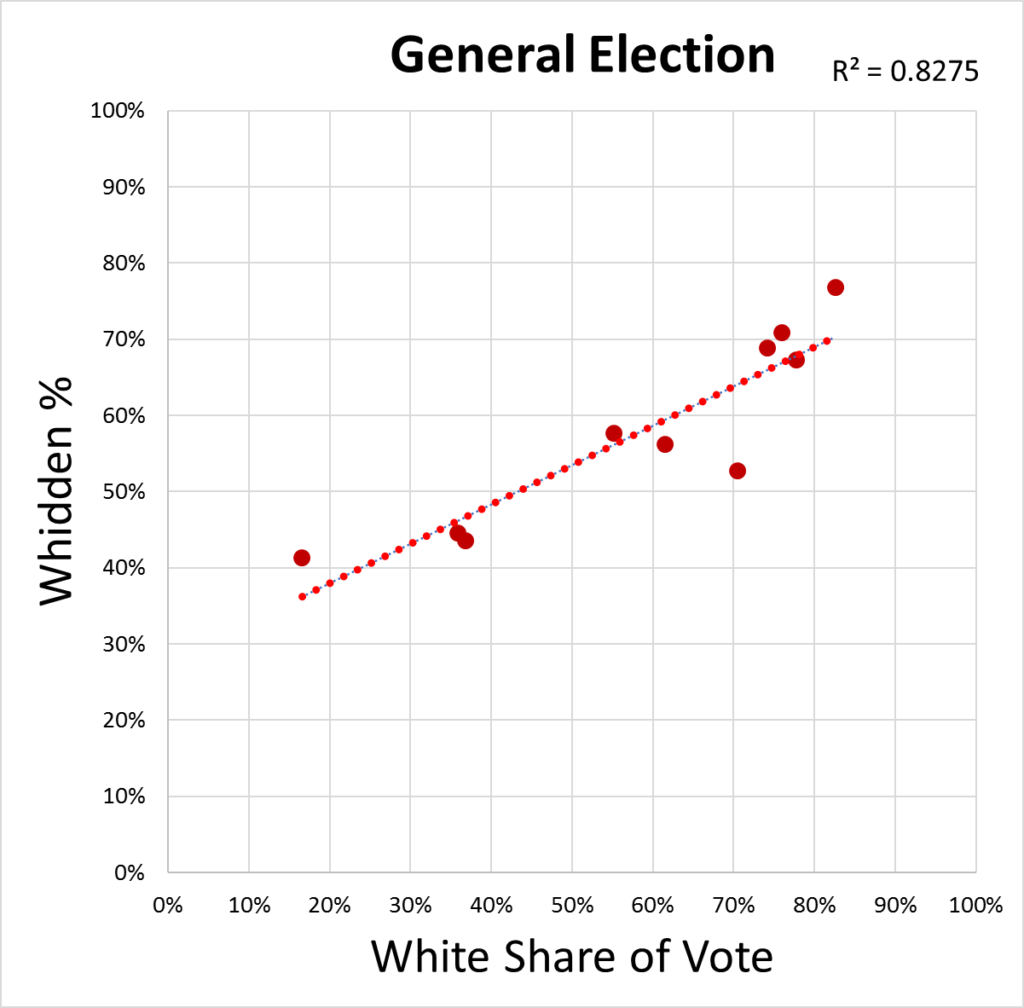

Whidden went on to face Ricky Garcia, an independent, in the general. Whidden won easily but Garcia notably won the three non-white precincts of the county.

Whidden had far more money in both races thanks to the support from US Sugar. Both races saw strong ethnic divides; with whites strongly backing Whidden and non-whites backing both his opponents.

These races were important to highlight as we move on to talk about racial voting in the county. Whidden’s opponents where both of another race and in both instances we saw high correlation based on race.

Hendry’s County Commission

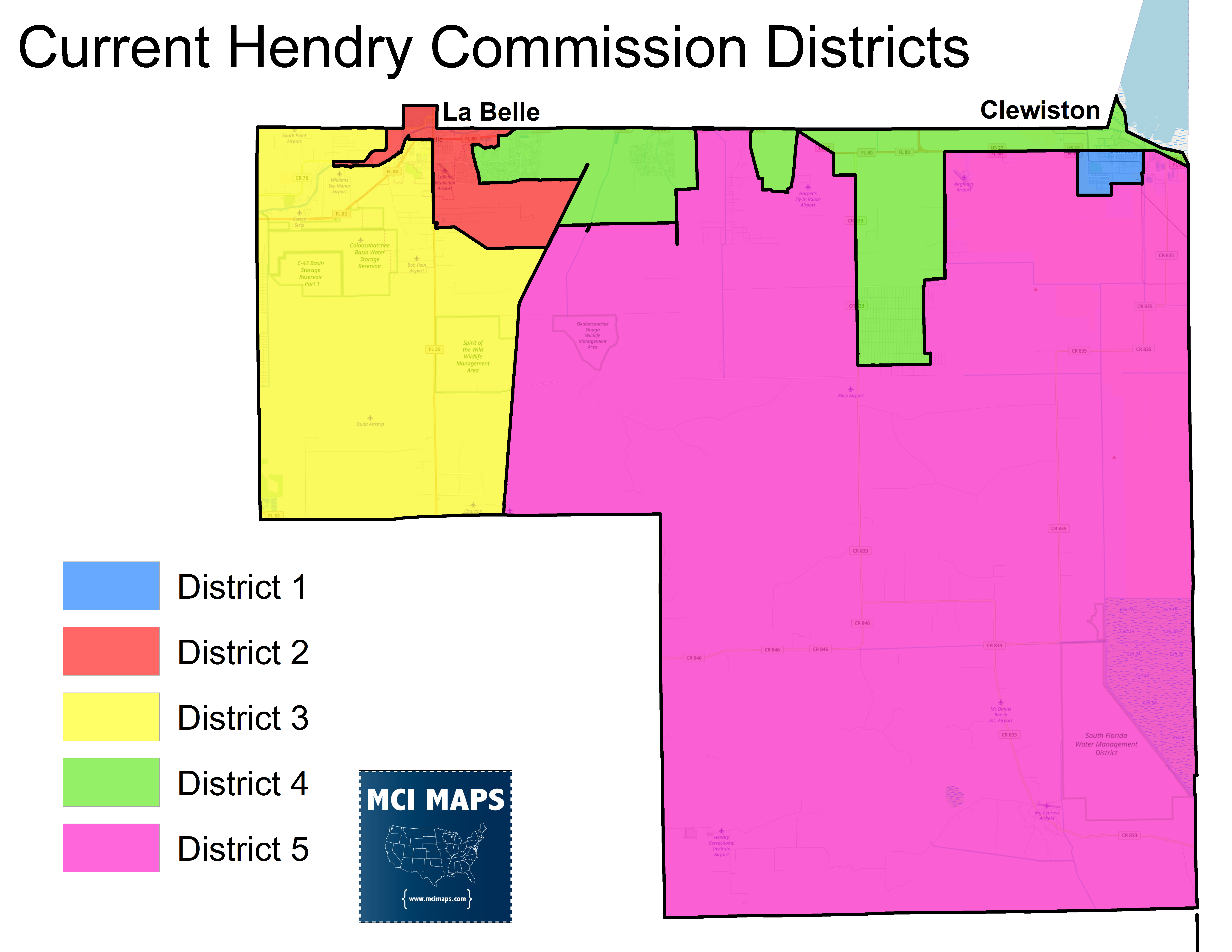

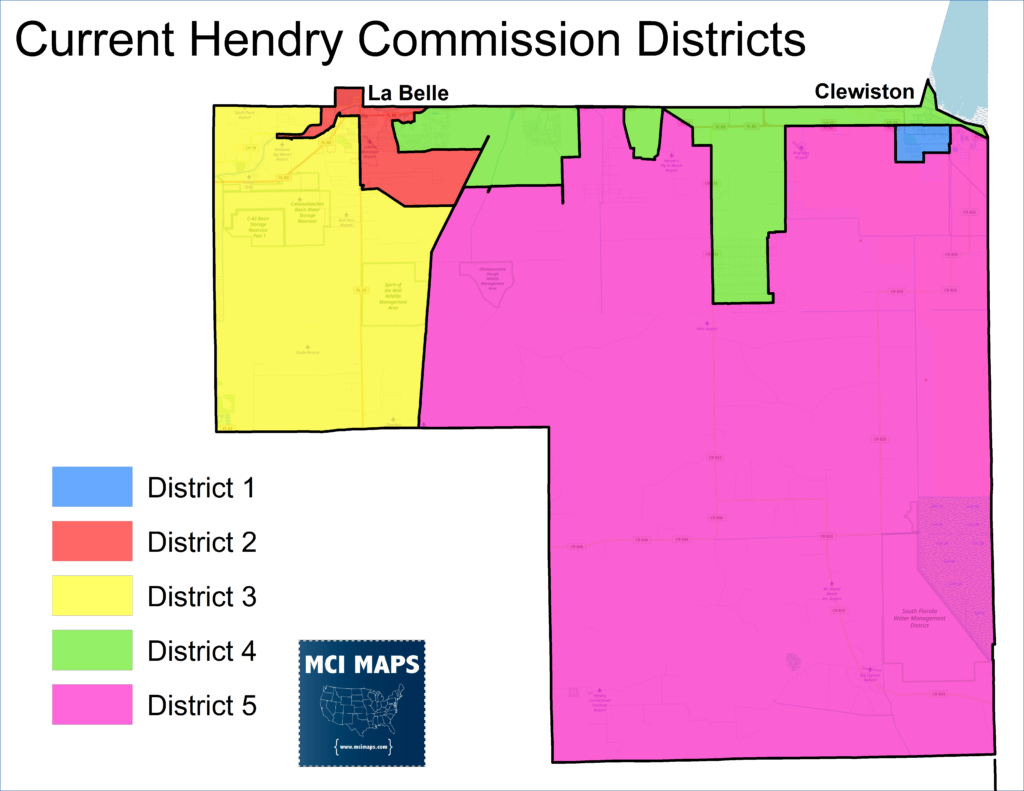

As stated earlier, Hendry County uses single-member districts. They do this as a result of a consent decree (an agreement with a judge) that came about from a lawsuit in 1991-1992. A group of African-American citizens had sued the county, arguing the at-large voting for commissioners and school board members ensured minority voters would never get representation on the either board. The county settled and agreed to go to single-member districts for the 1992 elections. That year saw the first African-American elected to the commission. Before these elections, Hendry’s county commission (and I believe its school board) was all white. Districts for the commission and school board are the same. These are the current lines.

The 1st District (same borders as precinct 1) is the county’s lone African-American district. It hosts Harlmen – an historically black community that lives just south of the Clewiston city limits. The remaining districts are all largely white and all have white representatives.

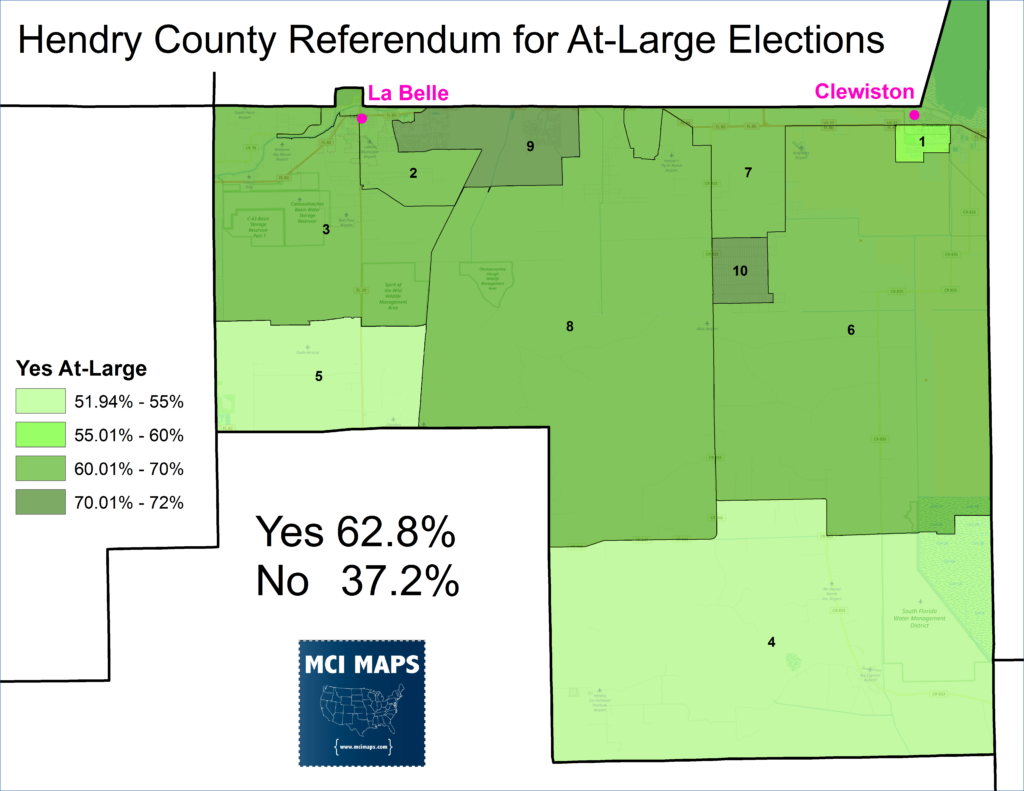

Then, in 2016, District 3 Commissioner, Don Davis, proposed a non-minding measure be put on the November ballot to see how voters felt about going back to the at-large system. Davis argued voters of the entire county should get a say in each commissioner election. Commissioner Taylor, of District 1, reminded the commission for the reason the county went to single-member districts. Nevertheless, the county commission agreed to put the measure on the ballot by a 3-2 vote.

The measure went on to pass easily. It won every precinct, including the African-American community.

The measure passed with little debate or campaign. For many, the measure being on the ballot was the first time they saw it or knew about it.

The same election saw Commissioner Davis lose his re-election to Republican Mitchell Wills and Commissioner Taylor lost her Democratic primary to Emma Byrd.

The commission finally began looking into the issue in mid 2017. An October meeting saw some stalling when the price-tag for the analysis (something that would be needed to get a judge to agree to lift the consent decree) would cost the county $40,000. For a small county; the price tag was too big. The commission moved forward with a much smaller price tag to get a general political science analysis of voting patterns in the county to see if the single-member districts are still needed to ensure minority representation.

Commissioner Byrd also pointed out concerns from her African-American constituents, who argued they had voted yes on a measure that sounded good without realizing the full implications of the proposal. Indeed the idea of at-large elections can sound good to just about anyone, but since no debate or pros and cons where given, and with many seeing the language for the first time at the ballot; its hard to argue the measure truly represents the informed will of the voters.

Are Single-Member Districts Still Needed?

Regarding the issue of if single-member districts are still needed. The answer seems to be clear: yes they are.

Hendry has a weak history of backing non-white candidates. It came close with Obama but each time he was still several points away. The racial splits in the sheriff’s race show a strong polarization. The county-wide officers are all white and races for Congress and State Legislature always see the white candidate win. During the commission debate over the issue, the county attorney pointed out Gulf County has considered going from single-member districts back to at-large. However, the county opted to stay single-member when it became clear the county’s African-American population would be disenfranchised. This is an important point. The Voting Rights Act makes actions that diminish the power of minority groups against the law. It is hard to argue moving to at-large wouldn’t diminish African-American voting power since their seat would be lost.

Creating an Hispanic Seat

Not only does Hendry need to keep single-member districts, but I would argue their current districts need a redraw.

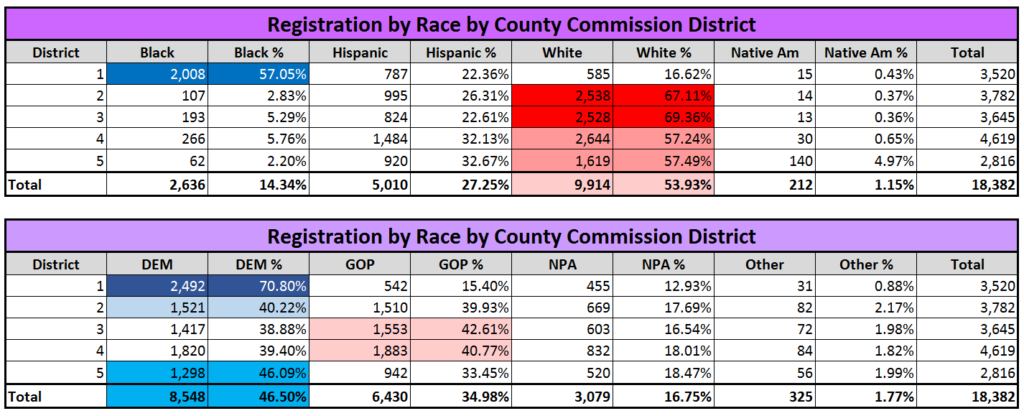

Hendry may be majority white in voting practice, but their Hispanic population is still large. However, right now no district boasts a strong Hispanic share of registered voters. Both the 4th and 5th districts have Hispanics at 32%. Full details below.

Partisan registration doesn’t play as large a role in local elections; with the county routinely splitting tickets. I wanted to include partisan numbers to make it clear I did not consider the map a partisan gerrymander. Rather, the partisan makeup reflects the county well.

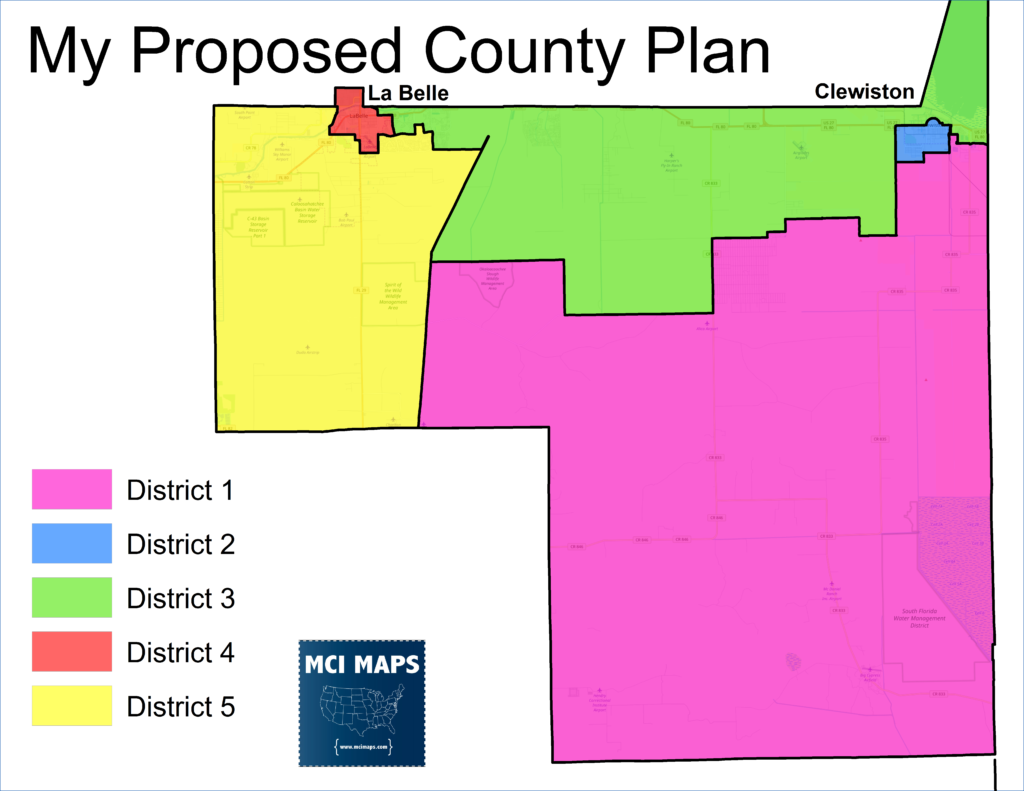

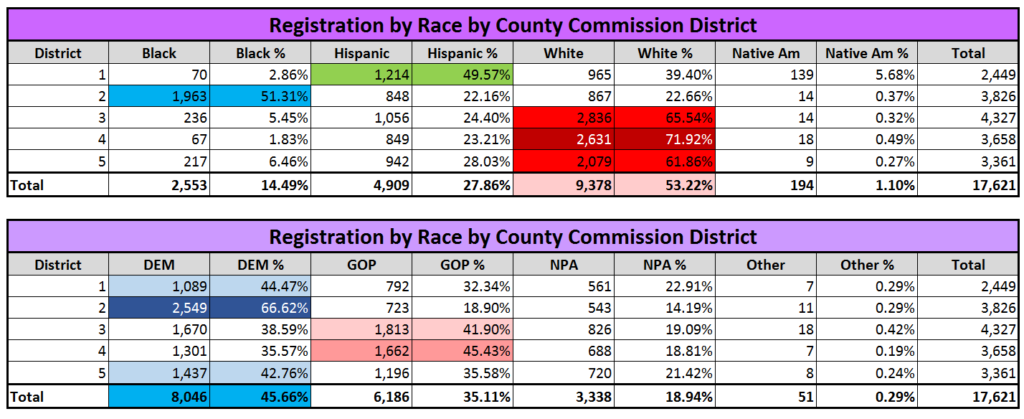

I believe that modest changes to the map can clean it up and give Hispanics a better voice on the commission. My plan is below.

The overall layout of the districts remains the same. I aimed to keep La Belle and Clewiston as whole as possible while balancing population and demographics as well as geography. The key change was giving majority-Hispanic Montura to the district that holds the Native American reservation rather than a district that is otherwise heavily white. Paring Montura with the reservation and other communities east of Harlem creates a Hispanic plurality district.

Not only does this plan better reflect the racial makeup of the county, we no longer have a district stretching from the north border to the south. My map is more mathematically compact while also workers to pair communities of interest and racial groups where feasible.

Nothing may come of the current lines now. However, when 2022 comes along (assuming the county is still using single-member) there needs to be a serious look at how Hendry draws its lines.

Conclusion

Ideas like at-large elections always sound good on paper. However, they ignore the reasons single-member districts sometimes exist. In some instances, single-member makes more sense for large counties where unique communities want advocates for their region. In Hendry’s case, the goal was to ensure racial minorities, in this case the African-American community, was heard. However, the county’s growing Hispanic population (in actual registration) means these lines need to be looked at again.