On October 1st, the beginning of the Halloween season, Bermudians will go to the polls for their parliamentary election. Ahead of this vote, I decided to talk about the politics of Bermuda and offer some insights into an area that many may only know as a line from a Beach Boys songs.

The History of Bermuda

Bermuda was originally discovered in the 1500s by Spanish explorers and had no native population; sitting well out in the middle of the Atlantic. Due to its spot in the path of major Atlantic storms and a dangerous reef that easily damaged ships – it never became a base of settlement. The first documented discover of the island was Spanish explorer Juan de Bermúdez in 1505 – but it wound up being the British who laid claim to the island. This occurred 100 years later when a 7-ship voyage to the struggling Virginia colony was hit by a storm and one ship, the Deliverance, was separated and diverted to Bermuda when it began to take on water. This began the British colonization of the island – which was added to the Virginia Company charter and its claim to the colony of Virginia.

Bermuda has remained part of the United Kingdom for its entire settlement existence. Its role has changed from a midway point in the Atlantic sailing routes, a source of major agriculture production, and eventually a move more toward a tourism destination. The archipelago is largely self-governing; electing a local parliament with a Governor appointed by the British. Officially the crown is the head of state in Bermuda, but the territory is largely self-governing on internal affairs.

Race and Ancestry in Bermuda

History

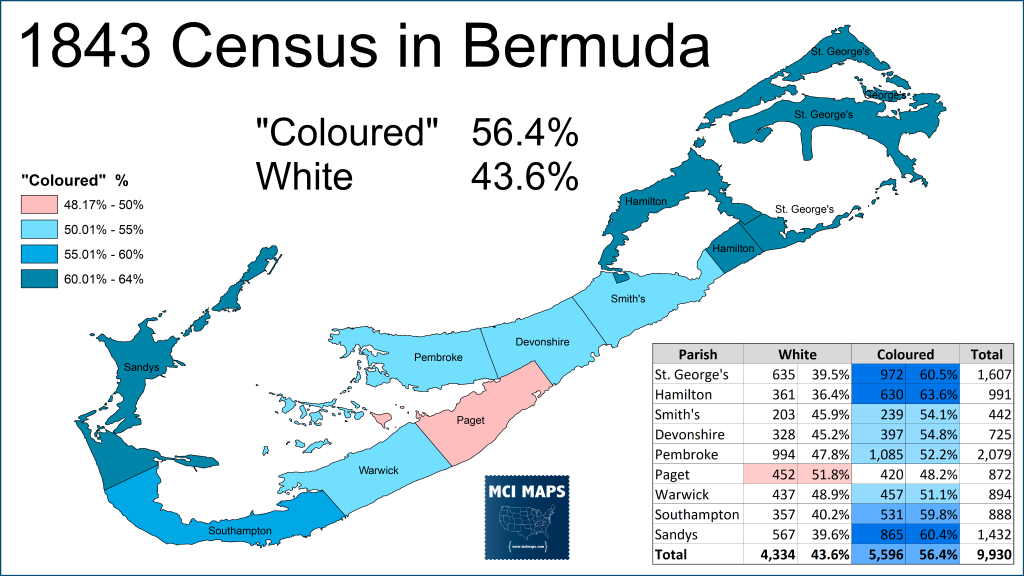

While its been established that British sailors were the first to settle the island, it was not long before Bermuda began to also import slaves; both African and Native American. The descendants of these slaves and migration from the West Indies has resulted in a diverse racial and ancestral makeup of the island. The history of race and ancestry in the islands is filled with the same tragedies, tensions, and discrimination that much of the New World knows. White settlers often regarded “coloured” (in this case a term for anyone not fully white European) as inferior and a burden on the food supply. Laws against mixed-race marriages were passed in the late 1600s, but this did not stop diverse families from emerging. A census from 1843 found 56% of the population classified as “coloured.”

Shifts in Bermuda’s population are two-factored. Mixed-race families were a common theme in the island and anyone not fully white European was deemed “coloured” and hence less than whites on the social hierarchy. In addition, many white Bermudians began to emigrate to the America. The island has always been in a position where, due to low land size, can only host so many residents. Whites seeking better opportunities (and in many cases a desire to flee a diverse island) leapt at opportunities to leave. “Coloured” Bermudians were much less incentivized to leave, especially after slavery was banned by the British but was still legal in America. However, many incidents of white residents driving out – (or as they said “encouraging”) – “coloured” residents are well documented throughout the history of Bermuda.

In many instances, slavery in Bermuda was better for the slave than in the American south. Slaves often worked in the shipping industry and were compensated for their work, though their master got an average of 2/3 the wage. This was much more preferable to the chattel-slavery of much of the American South – where humanity for the slaves was a non-factor. By and large being slave in Bermuda was a better deal than being a slave in American. One major result of this was that Bermuda experienced few slave revolts – especially in comparison to the Americas and other islands.

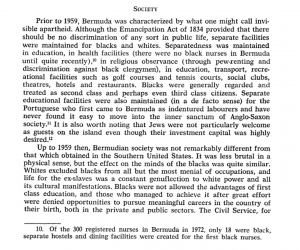

With emancipation of slaves, Bermuda, now majority non-white, still saw white residents retain advantages on the island and retain a racism against “coloured” residents. However, generations of close-quarter living resulted in less direct violence than occurred in other islands or the American South. This is of course not to say there were no racial incidents and by and large ‘colored” Bermudians were still regarded as 2nd class citizens. Well into the 20th century, the country maintain a “civil” outlook – but this could also be seen as an “invisible apartheid.” This passage highlights the issues.

Bermuda, which was already a popular tourist destination by this point, was eager to present a civil and peaceful society. However, this society was heavily segregated and designed to keep the white minority in charge.

How to Count Race?

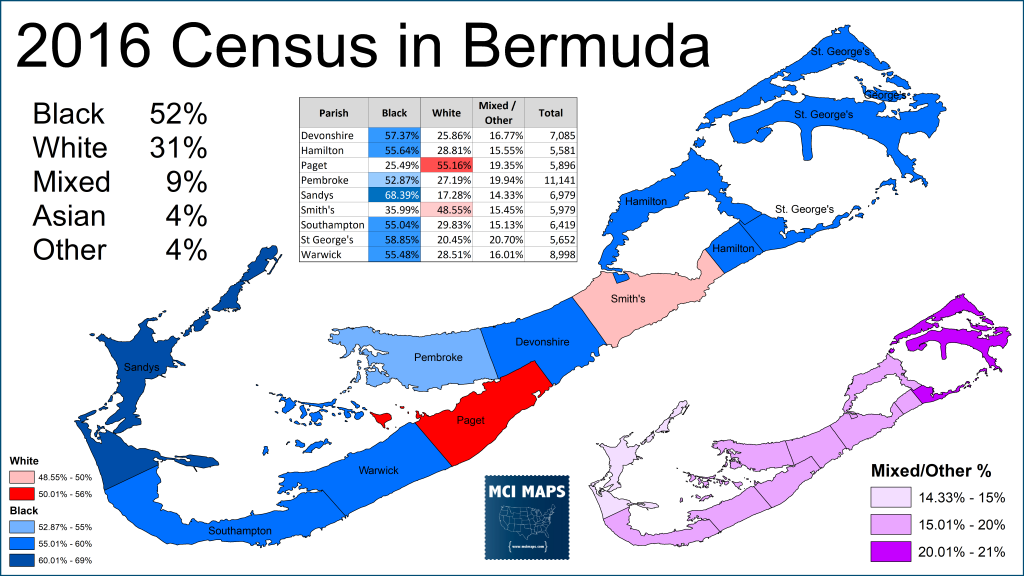

As the 20th century went on, the Bermuda government began to allow more diverse methods of counting its population’s ancestry. This led to a debate within the “coloured” community about census forms and whether to list the mixed-race ancestry many of them have or simply mark themselves as black. Debates like this emerge in many nations and come from issues of assuring populations are represented and resources are allocated. Many black Bermudians encouraged a single race listing to prevent the “coloured” community – as it has long been described – by being fragmented at a time when non-white Bermudians were aiming for more political and social equality. To this day, most non-white Bermudian’s list themselves as single-race black on census forms, but a growing segment opt to list multiple races to reflect their diverse heritage.

The non-white population of Bermuda, which as of 2016 is 69%, is divided into a few key groupings. 51% of residents described themselves as “black” in census documents, 9% as “mixed”, 4% as Asian, and another 4% going to other smaller groups.

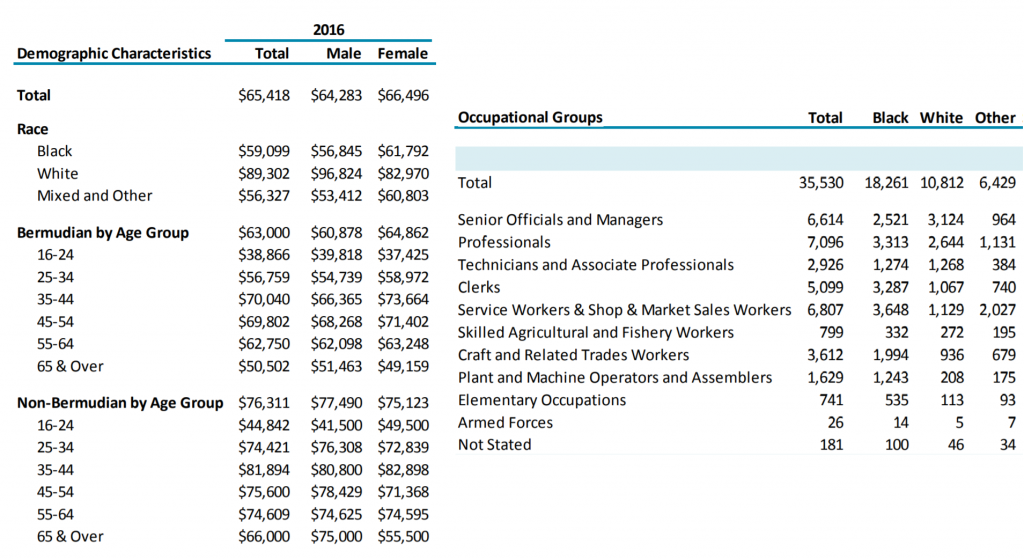

The debate in the non-white community about considering themselves “black” or mixed continues in Bermuda – especially as many black residents have some variation of non-African-black ancestry. The islands long history of mixed-raced marriages makes demographic breakdowns of the population subjective in many respects. However, the economic and social effects of the divide between the “white” and “coloured” populations are clear and still something at issue to this day – as white residents often have higher pay and more secure white-collar jobs.

This economic divide, which continues decades after segregation was legally ended, has put pressure on the non-white community to present a united front. That unity, as we will see, as now always come.

Bermuda has also seen major influxes of Portuguese people in the last century. Laborers from Portugal, or the Portuguese Island of Azores, have come into Bermuda to work low-pay agriculture jobs. An estimated 10% of the population has Portuguese ancestry at this point – though many speculate its larger. Like with US and its Hispanic population, tension has emerged in the nation regarding Portuguese people; namely citizenship rights and language. Longtime policy was to bring in laborers for temporary visas, but the common practice was continuous extension of those visas, leading to a population that lived in Portugal for decades but had no rights. With the 2008 recession, many visa’s expired and workers who’d been on the islands for decades were sent away.

The last century has seen major increases in the West Indian share of the population of Bermuda. In many instances the unity of the “coloured” population of Bermuda – many who trace ancestry for generations on the island – and newer migrants has not always been easily found. Tension with mixed-race Bermudians and Caribbean voters has flared for several decades. This divide spilled into the political arena as well.

In 1963, before party politics was legalized, the unofficial Progressive Labour Party formed with a goal of united the non-white population to win elections and push changes needed to even out the racial disparities in Bermudian society. However, this unity for a long time never came. the PLP had strong support with the West Indies population but Bermudian black and mixed-race residents split between the PLP and United Bermuda Party – which had near universal support from whites. This political divide, as the black population of Bermuda struggled with its own identity – further caused splits in the non-white population.

Early Bermuda Democracy

Property Owners Only

Before the 1960s, voting in Bermuda was a very restricted affair. Only property owners above 21 were allowed to vote; and in Bermuda this heavily favored white voters. When slaves were emancipated in the 1830s, the local government of Bermuda quickly raised the property value needed to vote. Property values had been 40 pounds. It was raised to 100 pounds. On top of this, whites could often count on property evaluators to inflate their value to ensure they met the voting standard. Many black property owners, by contrast, saw their values under-reported. In addition, a property owner could vote in each parish (back then those were used as constituencies) that they owned property in – and elections were done over several days to allow owners to travel from one parish to the next. In addition, if multiple people owned a single property, they all got to vote. White voters used their disproportional wealth and property ownership rates to inflate their vote share well above the census figures and maintained control of government.

Black voters would often rely on “pumping” – where they’d collectively agree on white candidate most sympathetic to their cause in a parish and focus on electing them. In other instances, black voters would put forth a black candidate to the white business elite and get a sign-off if that candidate was acceptable. As a result, the handful of black MPs in the parliament were beholded to white business leaders (many of the MPs themselves). This further gave the illusion of racial inclusion.

All an all, only 7% of the population of Bermuda could vote under this system. On top of this, many black land owners feared their mortgages and leases could be revoked if they were too outspoken for reform – putting them in a state of economic hostage. The sheer power of the white ruling class, which was powerful but not terror-inducing (like with the KKK in the American south) – also created a complacency and reservation among the black population.

Activism was kicked into high gear in Bermuda by the outside world. The civil rights movement in America was heard and seen on Bermuda TVs and radios. In addition, travel among Bermudians put many black residents into contact with civil rights leaders in America. By the late 1950s, pushes within Bermuda grew to change society -starting with boycotts of segregated movie theaters and hotels. Pushes for voting reforms also began to grow louder and from more people.

Reforms

Activism for change finally got the ear of the Bermuda parliament in the 1950s. The parliament worked on reform – all the while getting tremendous push-back from the powerful white property owners of Bermuda. At this point the parliament was dominated by white businessmen who operated a literal oligarchy on the island. These leaders, however, knew they were physically outnumbered and that violent suppression (as we’d seen in South Africa and other nations) would not be tolerated by the British Government and would suppress tourism. Reform had to happen, but they wanted to make it as modest as possible. Eventually, the Parliamentary Election Act was passed, which eliminated the property requirement to vote. However, two major issues diluted this reform. First, it gave property owners a SECOND vote. Second, it raised the voting age to 25. A major architect of the reforms – though he was himself disappointed more could not be passed – was W L Tucker, one of the few black MPs in Bermuda at the time. Activist Roosevelt Brown was also an instrumental figure in this movement – as he organized public demonstrations and increased citizen calls for reform. Tucker’s efforts, even when they fell short, have led to him being called “the father of the franchise” in Bermuda. While the reforms were not perfect, they were a stark improvement.

These reforms did spark deep divides within the black community; exposing a rift between a growing outspoken side of the black community (inspired by the civil rights pushes) and black voters who wanted to maintain good relations with whites.

The first elections under this mild reform took place in 1963 – with most candidates running as independents. The Progressive Labour Party had just been formed and was largely a left-of-center party calling for taxation reforms, social services, and ends to racial discrimination. It challenged 9 of the of 36 seats, winning 6 of the contests. The remaining seats were held by undeclared candidates.

In the next parliament, Henry James Tucker, a white MP, began to form what would become the United Bermuda Party. The UBP would be more center-right and while it had nearly all of the white vote, it also attracted black MPs and leaders. Tucker, seeing the political reality, worked to bring in black members and adopted several PLP issues, namely issues like free education and old age pensions. Tucker and the UBP would also support the end of school integration in Bermuda.

More reforms quickly came in 1966 to Bermuda, as a constitution was hammered out by Bermuda leaders in London to formalize self-governing for the islands. With this constitution, the voting age was lower back to 21 and the second vote for property owners was abolished. At this time, the parishes of Bermuda were divided into divisions; which elected two members. In addition, voter registration expired after one year.

The registration expiration and the two-member constituencies were both designed to help the UBP, which was better organized thanks to its ties to the longtime white oligarchy of the island.

The Emergence of Party Politics

A Post-Racial Bermuda?

The PLP and UBP’s time in the 1960s would set the political norm for several decades to come. As shown, the UBP and its leaders realized that they could not be seen as the party of just whites or the party of just the elites. This drove their move to adopt PLP ideas and support integration. Tucker laid out the situation on race directly

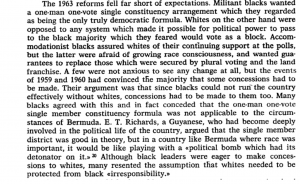

Unlike America, where whites were still a majority in the 1960s, race-bating politics could not work for the UBP. Racial harmony was the only winning strategy. The UBP worked to push this narrative hard and aimed to recruit middle class black voters. They were aided by many problems then PLP encountered at this time. The party was divided into two camps; those who favored a left-of-center approach to appeal to all working class voters, and more hardened left-wing members, some of who wanted to argue for united black identity. This view was especially popular with the Caribbean population; who I mentioned already had a tense relationship with the non-Caribbean “black” residents who had mixed ancestry. The Caribbean population was also less prosperous, having been brought into Bermuda to do lower-skilled work. They had nothing but negative association with the white business community. Within the non-Caribbean black community, these associations were more mixed and varied by class and personal connections.

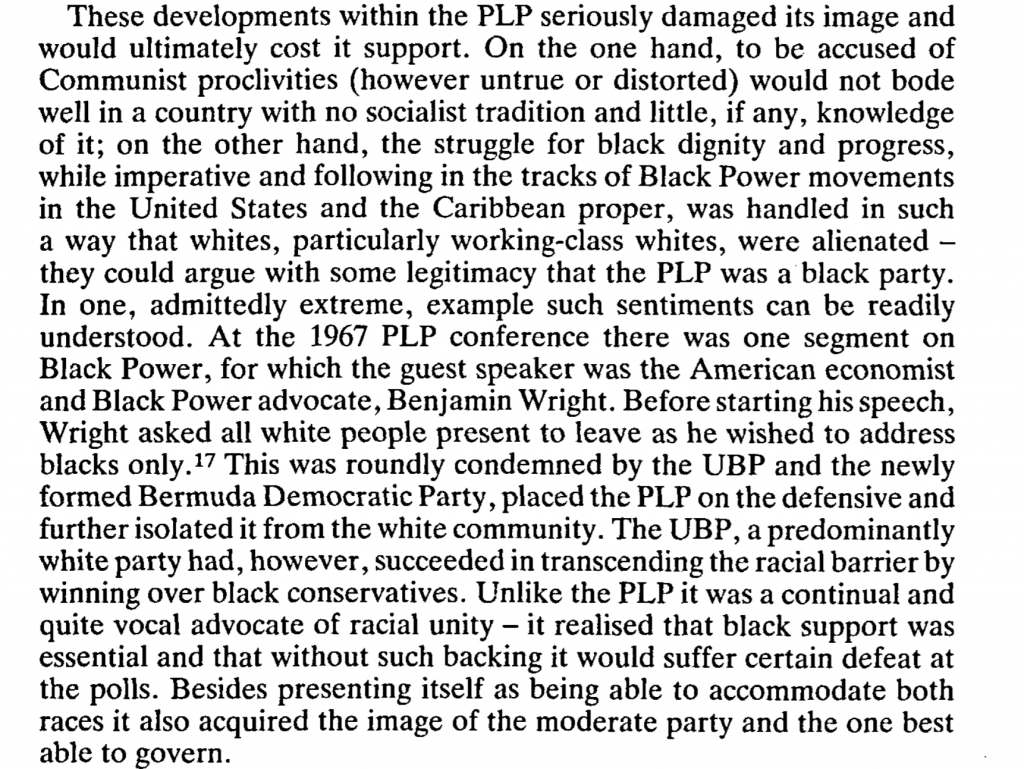

Two major incidents took place before the 1968 that hurt the PLP. First, a divide within the party emerged over how much the party should focus on just racial issues. Many members of the central committee were influenced by black civil rights leaders in the mold of Malcolm X. This led to a split between the central committee of the party and 5 of the 6 parliament members; who specifically accused members of the central committee of being too closely tied with “radicals” and “communists.” As a result these members were suspended by the party. Communist involvement was pretty overblown, but it did reflect a divide in the party between a more left-of-center and decidedly left-wing position.

The second incident can be seen below.

These incidents severely damaged the PLP; which was understandably still struggling with its own image. Decades of discrimination don’t just wash away for many, and the desire for a more forceful race-focused party was pretty understandable. This issue had divided the party from its earliest days. For many, being a “post-racial” party was just another form of bowing to the white minority that had been ruling the island for centuries.

The UBP was in a more advantageous position to consolidate the white minority with little issue and the sway over black voters, many middle and upper class, with unity talk and key issue concessions. The tensions within the non-white community, as discussed earlier, also made this split of the non-white vote easier to achieve. Unlike America, where most African-Americans in the 1960s had a centralized history, the non-white population of Bermuda was very mixed.

The PLP was in a bad position – as many of its most loyal followers were younger, more militant, and demanding changes now. This, however, scared off many blacks who favored a more consolatory tone with the white voters – who of course still had the vast majority of the economic power.

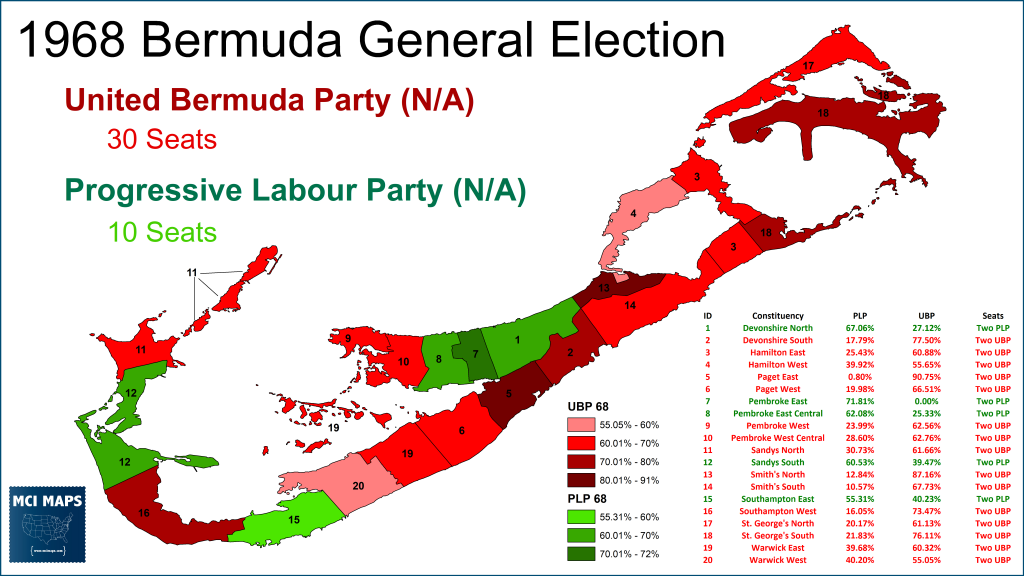

The 1968 elections, the first held with a voting age of 21 and no “second vote” for property owners, was a resounding win for the UBP, which got 30 seats compared to the 10 for the PLP. Tucker became the first Premier of Bermuda under the new constitution.

With such a commanding win, an era of dominance for the United Bermuda Party was about to begin.

The Era of UBP Dominance

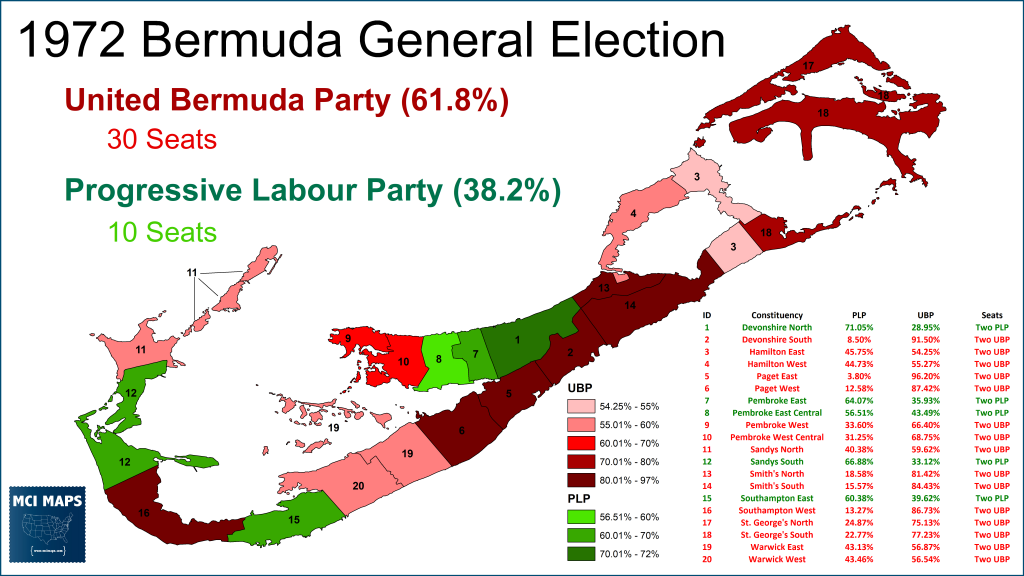

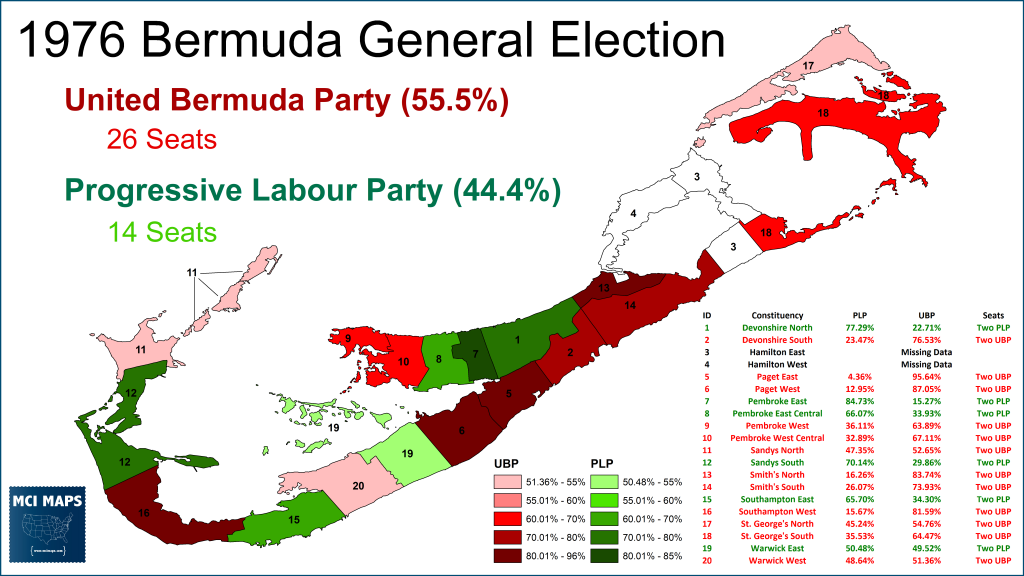

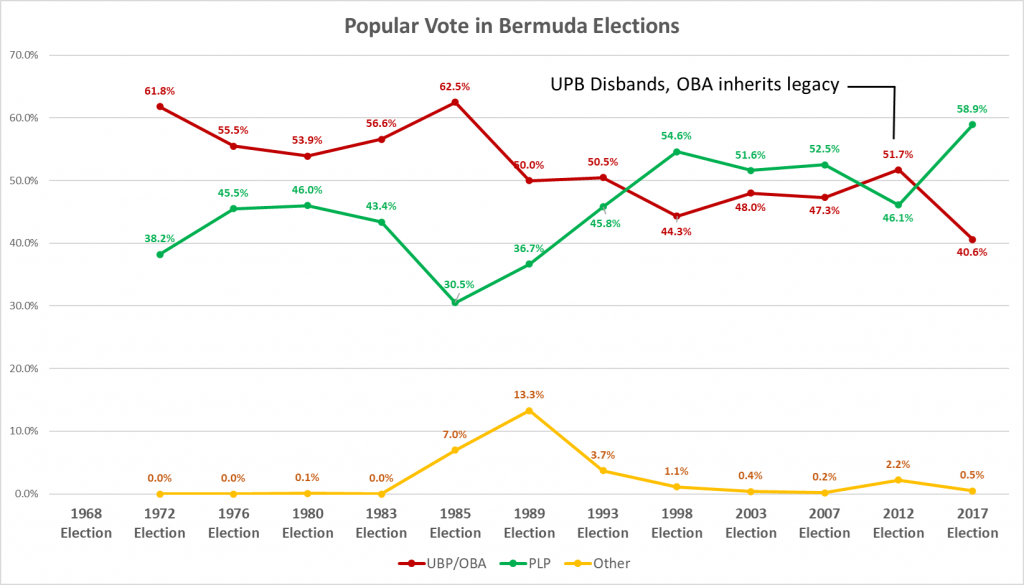

The UBP navigated the 1970s by continuing to adopt post-racial language while generally maintaining a center or right-of-center policy position. In 1971, the UBP elevated Edward Richards to leader, and hence Premier. Richards was the first black premier of Bermuda. The party won 61% in the 1972 elections under his leadership. The party would win 55% in the 1976 elections.

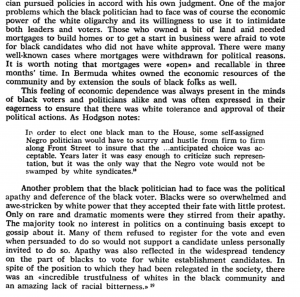

During this time, the PLP struggled to find a united identity to rally around. The image of the party had been damaged in the 1960s, and to be honest, the party did little to fix that after the fact (whether fair or not). However, it is worth noting that one thing also hurt PLP involvement, and that was an underlying racism with white voters. While the racial tension didn’t get to the church bombing stage of Alabama, there was still a clear racist viewpoint in many Bermudian whites. This became more apparent when white professionals opted to join the PLP and faced major backlash.

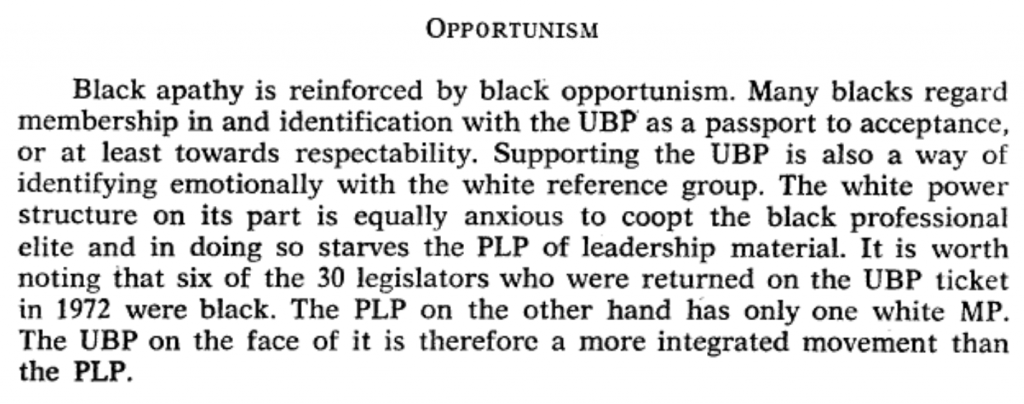

The PLP’s image has a “black party” became a self-fulfilling cycle. White members where not encouraged to join by the PLP itself (which by and large did aim in the 60s and 70s to unite the majority black population more than recruit white followers) BUT the racism of whites that would bubble to the surface when whites tried to join also had a major impact. On the reverse end, blacks who joined the UBP didn’t suffer the same economic effects, as being part of the majority party offer any economic opportunities lost in the transition. This outtake from a 1970s article highlights the dynamic well

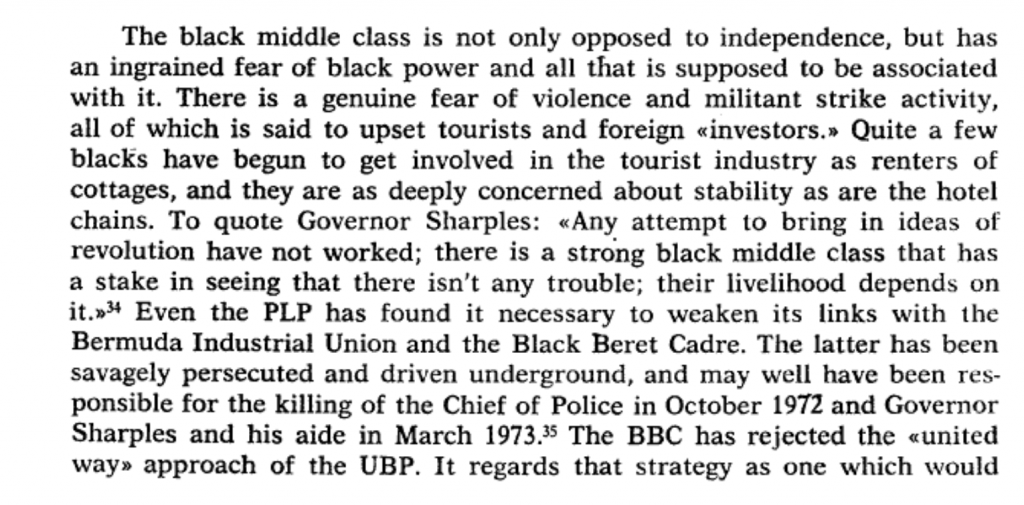

Racial tension continued in much of the 1970s. Several protests and strikes took place in the 1970s and early 1980s of wages and economic opportunities. In many instances the UBP worked to adopt the issues being pushed and avoid giving black voters they had won over any reason to defect. In fact, many black voters privately encouraged the PLP and young black activists while at the same time maintaining a public support for the UBP.

By the mid 1970s, the PLP did begin to see its racial problem was not going to go away and began to work towards a less militant racial tone and tamp down its support of independence.

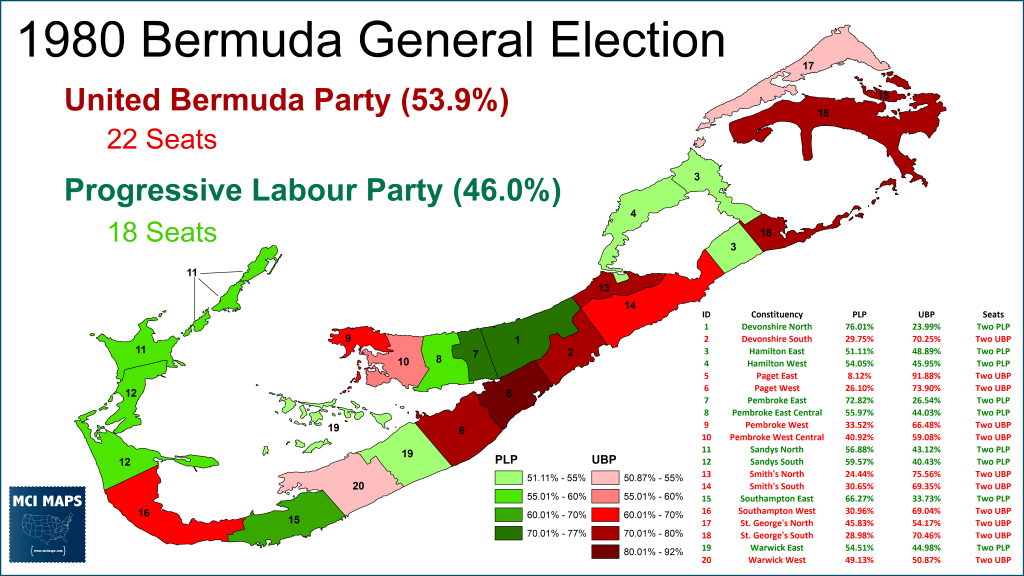

The UBP’s post-racial narrative continued to keep it in good graces; though they did encounter problems under the leadership of David Gibbons. The island was hurt by the 1970s recessions that plagued many parts of the world and the fortunes of the PLP rose with those economic uncertainties. The PLP was able to re-attract some black support and support from younger whites who found few job opportunities. The 1980 election would be the closest in Bermuda to that point, with the PLP coming within just a few seats of winning.

The UBP recognized the problem and quickly changed leadership; electing another black leader in John Swan.

Again the UBP was able to successfully define itself as a post-racial party. Meanwhile stories of the whites who aimed to defect to the PLP were often never widely reported. This was aided by pro-UBP bias in the media.

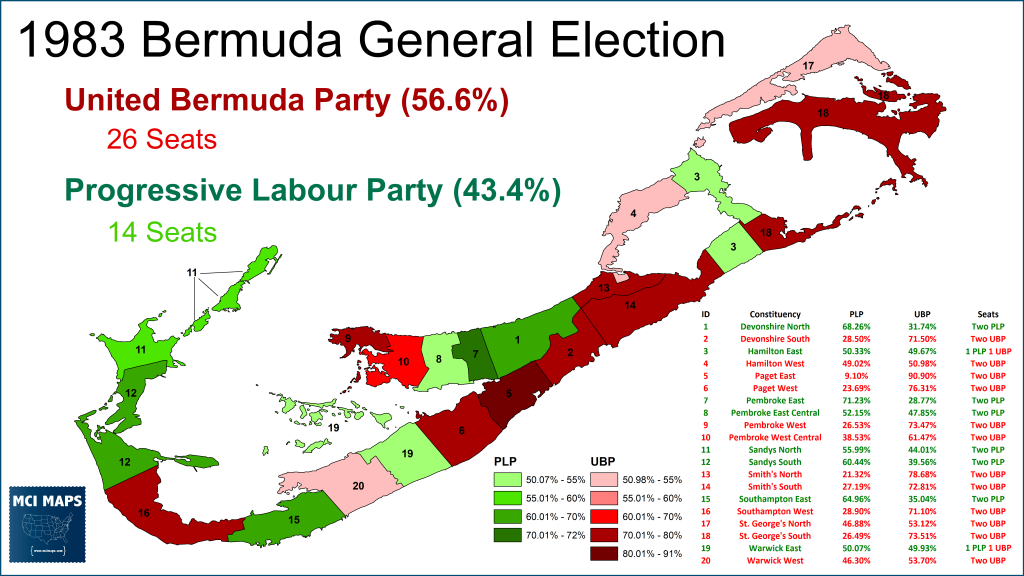

Under the leadership of John Swan, and with a growing economy of the 1980s, the UBP was able to rebound in the snap 1983 elections, gaining back 4 seats and winning 56% of the vote

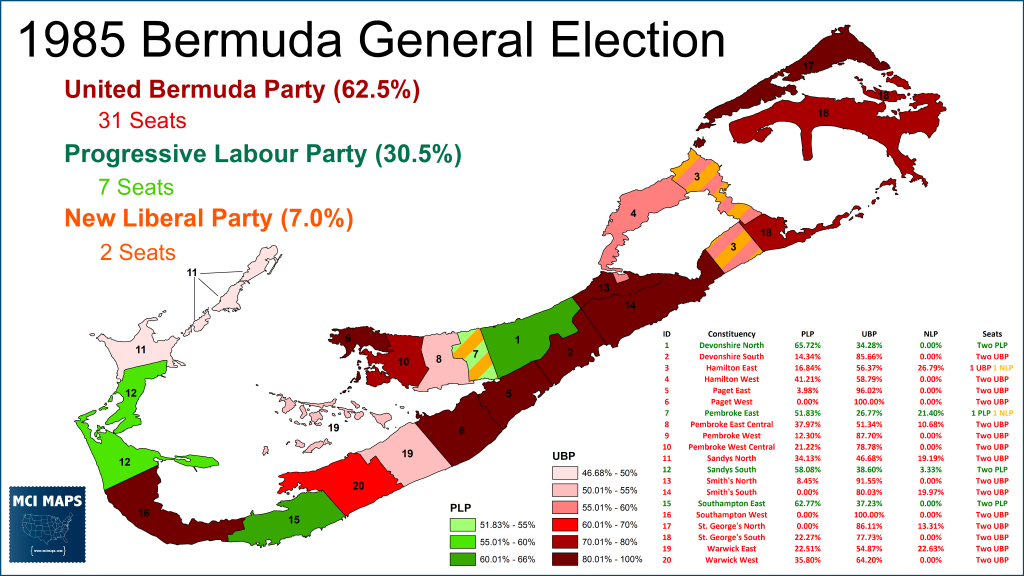

This slide-back for the PLP was the last straw for many members – who began loudly calling for new leadership and a change in party outreach and issue positions. Several members argued for change in direction and a more moderate tone. This opened up a clear divide between elected members and the party central committee (not unlike the divide that existed in the UK Labour Party with MPs and those supporting Leader Corbyn). Several “dissident” MPs were suspended by the party’s central committee and later expelled entirely. These members went on to form a new political party, the National Liberal Party (NLP). The party was ideologically in-between the PLP and UPB, but in the 1985 snap election, they took 6% – almost exclusively from the voters sick of the PLP. This caused the PLP to lose 7 seats.

The advent of a new party didn’t alter the broad state of party politics, however, as this 1980s publication laid out. The UBP entered a steady state with John Swan as its leader (all the way until 1995 in fact). That steadiness, however, caused rising tension within the UBP itself and racism began to creep up.

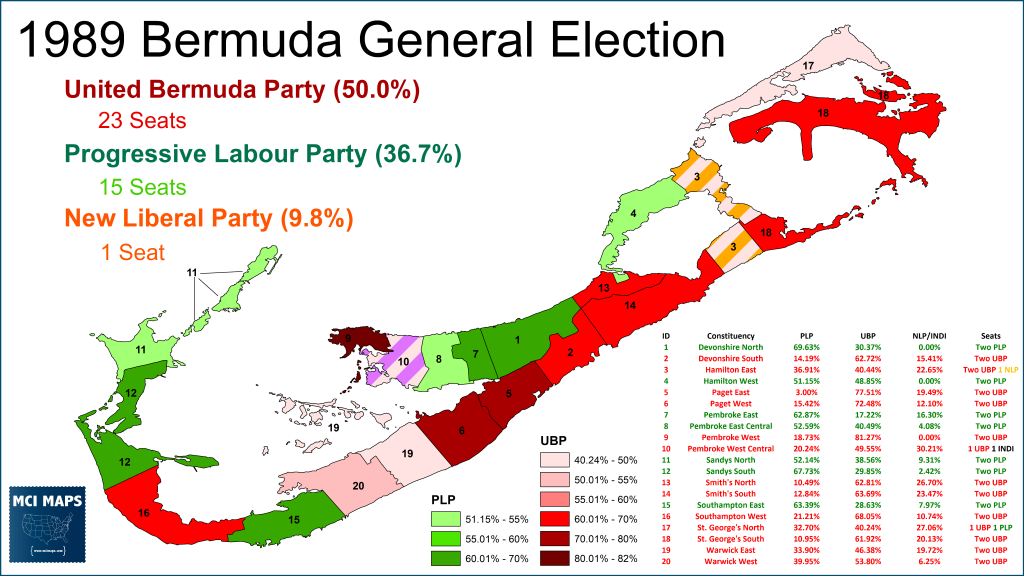

The 1985 loss saw a PLP new leader, Frederick Wade, elected. Wade focused on party rebuilding and trying to heal the losses. In addition, the party began to make more efforts to appeal to middle class voters and build support with a younger generation less bound to the allegiances of the 1960s parties. A new election was held in 1989, and the PLP was able to rebound, taking 15 seats. The New Liberal Party only managed to hold 1 seat despite increasing their popular vote share. Meanwhile, one candidate was elected as an independent. This would mark the height for the New Liberal Party, as they’d quickly fade after this.

Heading into the 1990s, the PLP would continue its party rebuilding efforts. Meanwhile, the UBP would suffer from internal divisions that would finally see it fall from power.

The Rise of the PLP and fall of UBP

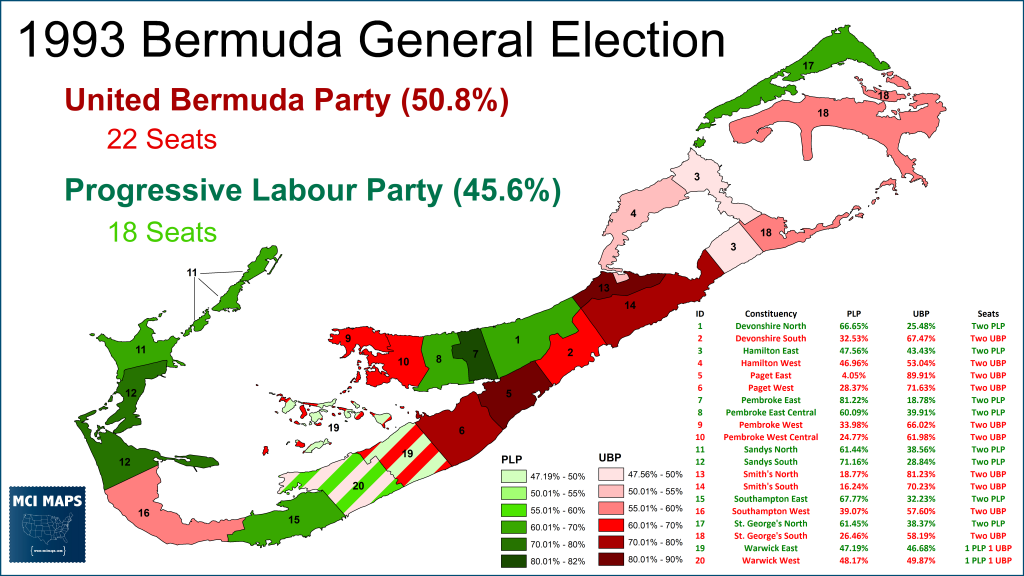

The PLP continued to rebuild itself and went into the 1993 election at its strongest point yet. The 1993 election results saw a 22-18 split, with the UBP barely holding on to its majority.

After the election, a heated debate emerged in the territory over independence from Great Britain. The PLP had long support independence, but moved away from that as a focus in recent years. Meanwhile, John Swan, the longtime head of the UBP, was a supporter of independence. Swan looked to hold a referendum on the independence issue. This bitterly divided the UBP, with many being ardent supports of remaining with the British (many if not most of course tracing their lineage to British settlers). This divide within the party did not prevent Swan from getting the needed votes in parliament to put the measure to a vote in 1995.

Swan may have gotten the vote, but the PLP, sensing blood in the water, declared it would not support the referendum and urged its voters to boycott the vote. The referendum needed high turnout to pass, and a PLP boycott would make its results invalid. The PLP argued that such a discussion should only come after other structural reforms took place in Bermuda and rejected a rash referendum on the issue.

The referendum came and only say 25% support independence with just 58% turnout. Many PLP voters likely did show up to vote no and cause a blow to Swan, who also clearly did not have rank-and-file support from UBP voters on the issue. Swan subsequently resigned as Premier of Bermuda after the referendum.

A second controversies arose in 1995 and carried into the next several years – McDonalds!.The controversy arose around the law in Bermuda that banned foreign ownership of businesses in the territory. This effectively banned fast food franchises. A McDonalds did exist on the island, however, thanks to it being on a US Navy base. When the base closed in 1995, the McDonalds, which was visited by many locals, had to go with it. It was revealed that now-former-Premier John Swan had sought to franchise a McDonalds for the island. The UBP had long been in support of the restrictive law, which was designed to keep wealth on the islands, but the efforts by Swan divided the party. The supports of Swan’s efforts were viewed has hypocritical and the PLP quickly latched onto the controversy, siding with 5 break-away UBP members to pass a law extending the restrictions on foreign businesses. Swan appealed the law and a multi-year debate over the issue brewed. David Saul, who became Premier and UBP head after Swan’s resignation, only lasted until 1997 before he resigned amid deep party division.

An election came in late 1998 and the UBP was bitterly divided on multiple issues. Jennifer Meredith Smith came to take control the PLP after the death of Leader Fredrick Wade, and her efforts to build the party’s apparatus and broaden its appeal continued what Wade started.

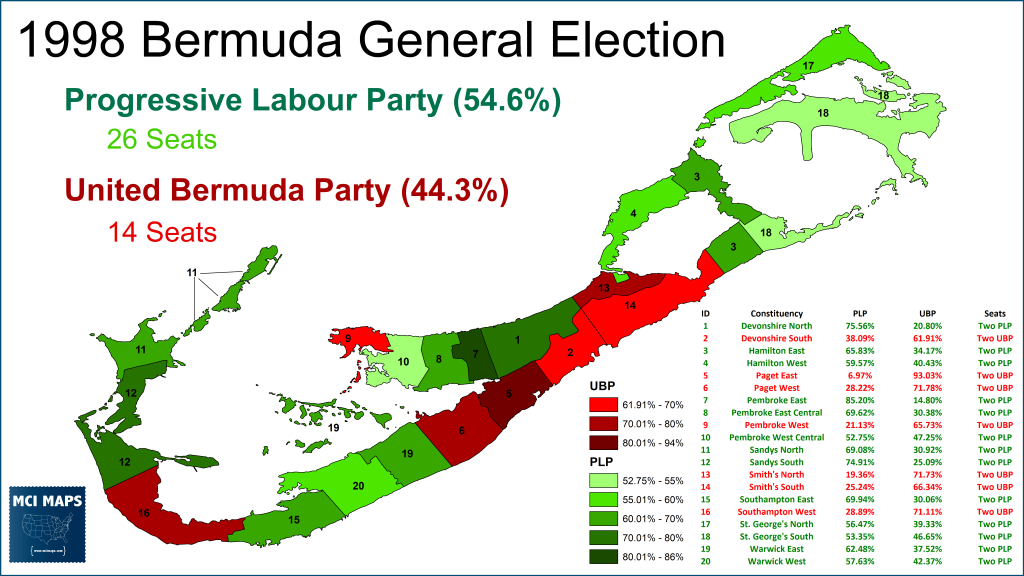

With the UBP divided and the PLP at its strongest point, the three-decade single-party dominance came to an end. The PLP won 55% of the vote and took 26 seats.

With their win, the Progressive Labor Party began to make a series of reforms to Bermuda policy and elections. Their platform, known as “A New Bermuda” saw several changes in all aspects of policy.

Post 1998: PLP & Election Reforms

One issue that the PLP had long taken issue with was the two-member constituencies. This breakdown often did not account for proper population distributions and implicitly aided the white minority. The PLP had long staked out support for single-member constituencies while the UBP favored the current system. Both parties did stipulate it was the right of the winner to offer reform to this system. As such, the PLP did move to change elections to single-member constituencies. The territory would go to to be divided into 36 districts; resulting in 4 fewer MPs after the next scheduled elections. The PLP also eliminated the one-year expiration of voter registration and passed laws to increase the types of ID’s that would be valid for voting. These changes and constitutional amendments were subsequently approved by the British Government.

Other PLP reforms included increasing of social services, from major aid programs all the way to increasing trash collection. Once the election reforms were legally cleared, Premier Smith called for an election.

The PLP reforms were broadly popular, however one growing liability for the PLP was Premier Smith. The premier had worked tirelessly to get the reforms through and in the process angered many MPs with a closed-off kitchen cabinet and brash personality. By the time of the election, polls showed the parties neck and neck but 60% saying they wanted a new Premier regardless.

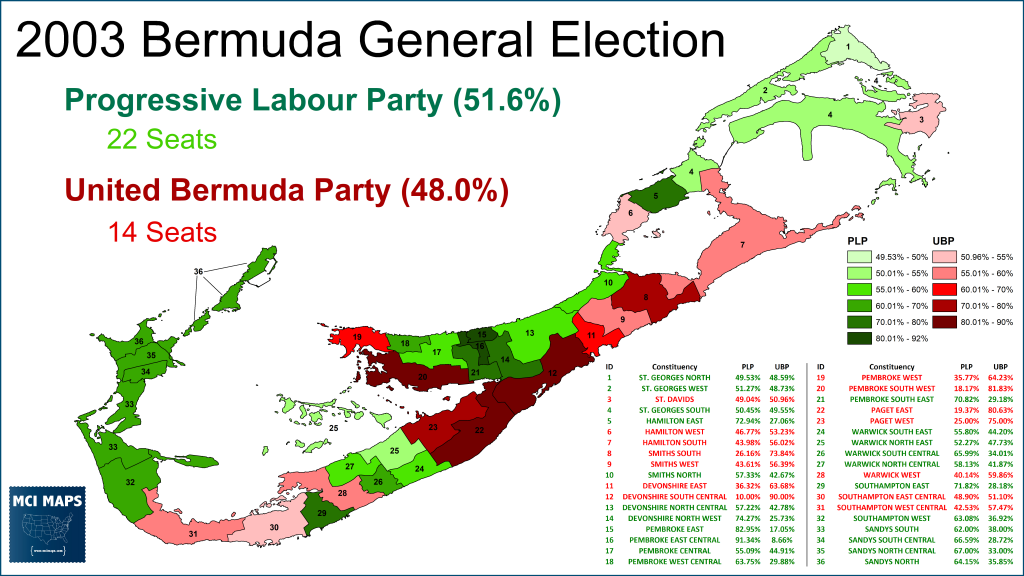

In the end, the election results marked a sign-off of the PLP’s reforms. The party won a narrow 3% win, but won a solid number of seats by narrow margins. Landslide losses in white-majority districts made the vote much closer, but the PLP held on. Smith, herself, only won her district by a handful of vote.

Trouble for the PLP emerged the night of the election though. Smith faced a revolt from 11 of the 22 elected MPs; who insisted on a right for members of parliament to chose the Premier (which until this point had always been the head of the party itself). The rebellion was motivated be personality and ambition vs ideology. Many MPs said Smith was too heavy handed and that the narrow results were closer than they should have been. Smith pushed back on the personality attacks, stating ‘I cannot be other than I am.” Smith pointed out 90% of the PLP platform had been achieved in the first term, and that her arm-twisting for several reforms was needed – this however was apparently a major driver in MP anger, which was kept private from voters before the election. However, warning signs had existed before the vote, as Smith had seen challenges that failed already.

The main candidate to take on Smith at a party meeting was Transportation Minister Ewart Brown. However, to pacify both sides of the party, compromise candidate Alex Scott was chosen to become the new Premier. The incident provoked a bitter split in the party between Smith loyalists and the rebels. Grassroots workers, who were happy about the reforms Smith had pushed through, were deeply angry about the change in leadership and Smith became a martyr to many of them.

Scott’s tenure would only last a few years. In 2005 he began a push for another look at independence, but this effort never made it to the referendum stage. In 2006, Ewart Brown, who had been Scott’s deputy leader, resigned and challenged Scott for the leadership, winning support and becoming the new Premier.

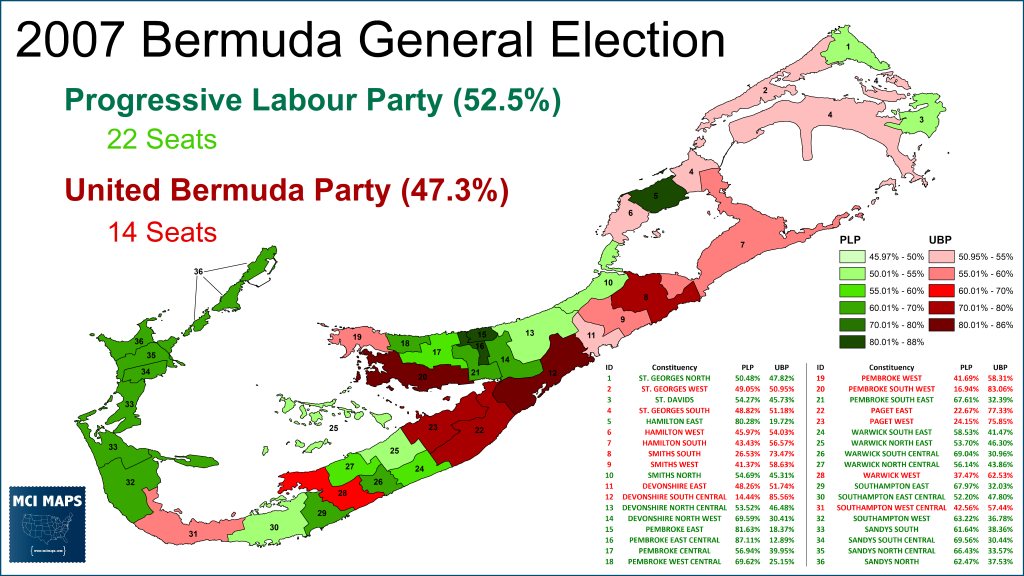

Brown has proven to be a controversial politician in Bermuda – with a similar brash style as Smith. Brown, however, led the PLP into a successful 2007 campaign by working to coalesce the PLP as the party fighting for black voters on the island. The race took on a very heated tone around race; with accusations coming from black former UBP members that the party was still controlled by white businessmen and Smith being accused of pushing race instead of policy. Controversy erupted when the postal service confiscated a letter sent to Smith with a bullet inside.

The election saw the PLP gain in popular vote but hold the same number of seats; though some districts changed hands. The UBP, shocked by its loss, outwardly stated they believed race hurt them. Michael Dunkley, the white leader of the UBP, lost his own seat.

Following the election, the United Bermuda Party began to see cracks. In 2009, six UBP members (4 black, 2 white) defected from the party and formed the Bermuda Democratic Alliance party. The party said a new opposition to the PLP was needed, and largely retained the same lane of the spectrum as the UBP. In a subsequent bye-election (special election), the BDA contested the open seat along with the PLP and UBP. The results, and subsequent polls, showed the UBP and BDA taking from the same pool of voters; while the PLP retained its supporters.

Realizing any chance to win required united, the BDA and UBP eventually agreed to re-merge and form a new political party; the One Bermuda Alliance. Craig Cannonier, a black MP, became the party’s first leader.

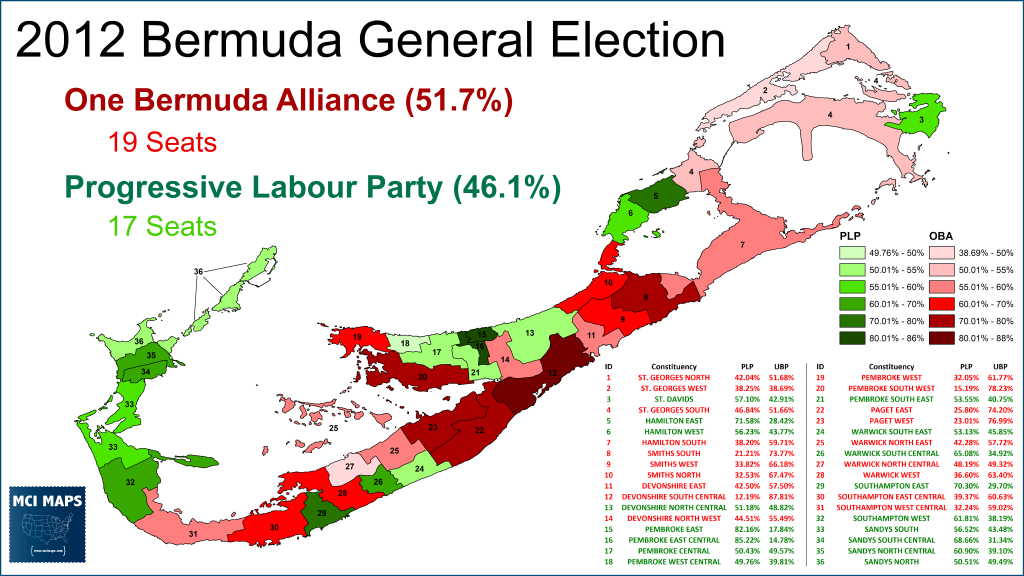

In 2010, Brown would step down as Premier and be replaced by MP Paula Cox. She would have a rough time in power thanks to global recession. From 2009 until the 2012 elections, Bermuda saw negative growth as the tourism industry was badly damaged. When voters went to the polls in 2012, they ranked the economy as the top issues. The poll showed 50% were unhappy with the country’s direction and only 19% were happy. The poll revealed that the PLP was suffering with black voters, who only believed the PLP was best to lead a recovery over OBA by 38% to 26%, with 30% undecided. White voters, however, favored the OBA by a 90% to 1% margin. Polls also showed Cox with a 34% approval rating. Like many governments worldwide, the recession was a major burden on the ruling party.

When the election came, it was a solid loss for the PLP. The party fell to 46% of the vote and lost 5 seats. Premier Cox lost her district as well.

Over the next few years, the economy would begin to turn around in Bermuda as tourism improved. However, the OBA was hurt by several issues and scandals. The first was the “Jetgate” controversy. In 2014, Premier Craig Cannonier was forced to resign when it was revealed that he and other OBA members had flown on a private jet to meet US businessman Nathan Landow and subsequently secured $300,000 in funding to run the OBA’s 2012 campaign. While the OBA insisted no strings were attached, it was well known Landow wanted to build a casino on the island. With Cannonier out, the OBA tapped Michael Dunkley, the former UBP leader who had lost his seat in 2007 (and subsequently won a seat in 2012). The selection did not help the OBA, however, as they had handed the party to the leader of an old party and one of the richest white men in the territory. The PLP would go into the next election with Edward David Burt as its leader.

The OBA was forced into a vote of no-confidence in 2017 when two members left the party and sat as independents; triggering an early election. The campaign saw the OBA campaign on the improved economy while the PLP argued that “Two Bermuda’s” saw the improvements differently – as recovery had not come to all residents. The election also saw the PLP take on a more populist and protectionist stance while the OBA took on a free-trade and globalist position. The PLP, however, retained a more left-of-center domestic spending position than the OBA’s right-of-center stances.

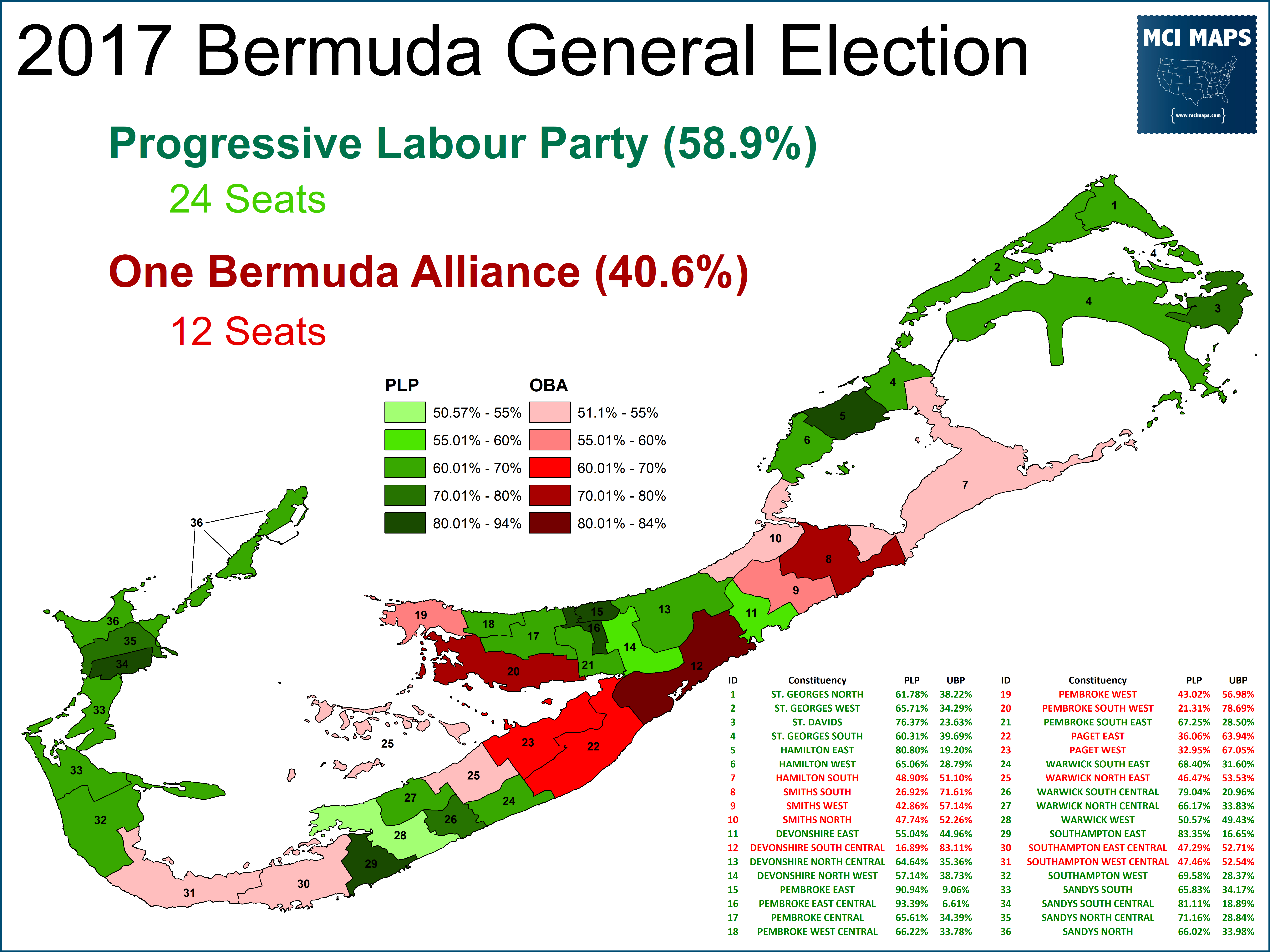

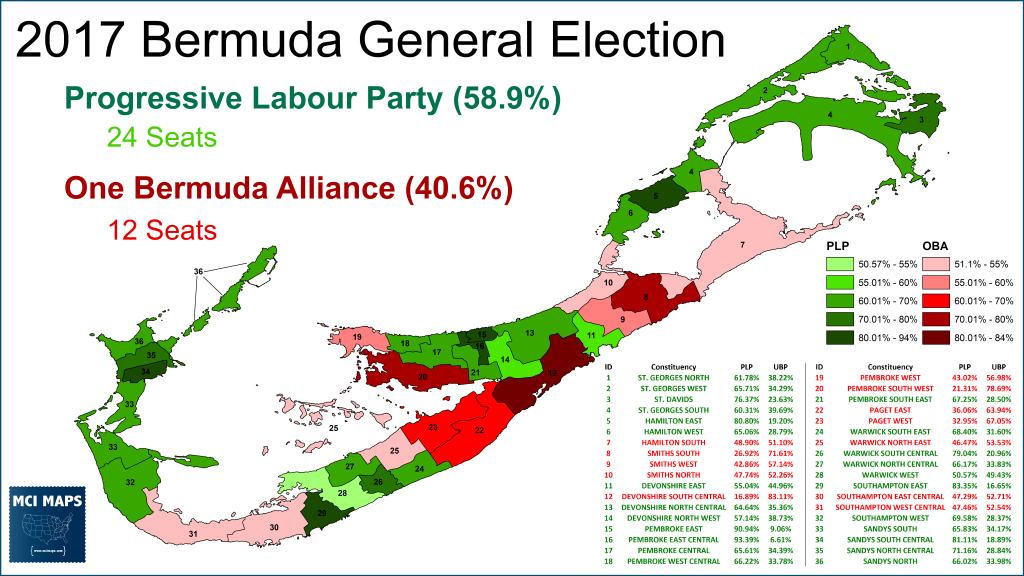

The PLP went on to have a landslide election night; taking 59% of the vote and winning 24 seats.

The results showed just how strong support for the PLP had grown in the country. Despite the recession, the PLP had only narrowly lost its majority in 2012. With the economy improved, the PLP was the clear winner; taking its highest share of the vote. By all accounts, this is now an era of PLP dominance.

The OBA struggled with internal debate for the next year, forcing its new leader, Jeanne Atherden, to step down. In a intriguing turn of events, Craig Cannonier, formerly forced out in scandal, returned to head the OBA.

The 2020 Election

Like all countries, Bermuda has been dealing with the COVID pandemic – especially its effects on tourism. Premier Burt has subsequently decided to call a snap election. The election will be held October 1st. His argument is that tough financial decisions lie ahead and a mandate is needed. There might be a political incentive as well – that the PLP believes it can win a landslide on the 1st. The OBA is not ready for the election, something that became clear when they opposed the move. In addition, a new party has emerged on the center-right. The Free Democratic Movement Party has been founded by Marc Bean, who was actually the PLP leader after the 2012 loss, but had resigned from politics before 2017. Bean and his party are right-of-center and believed to take more votes from the OBA than the PLP.

A recent poll puts the PLP in a commanding lead with over 50% and the other parties splitting the vote. Over 90% of voters also favor the government’s handling of the pandemic.

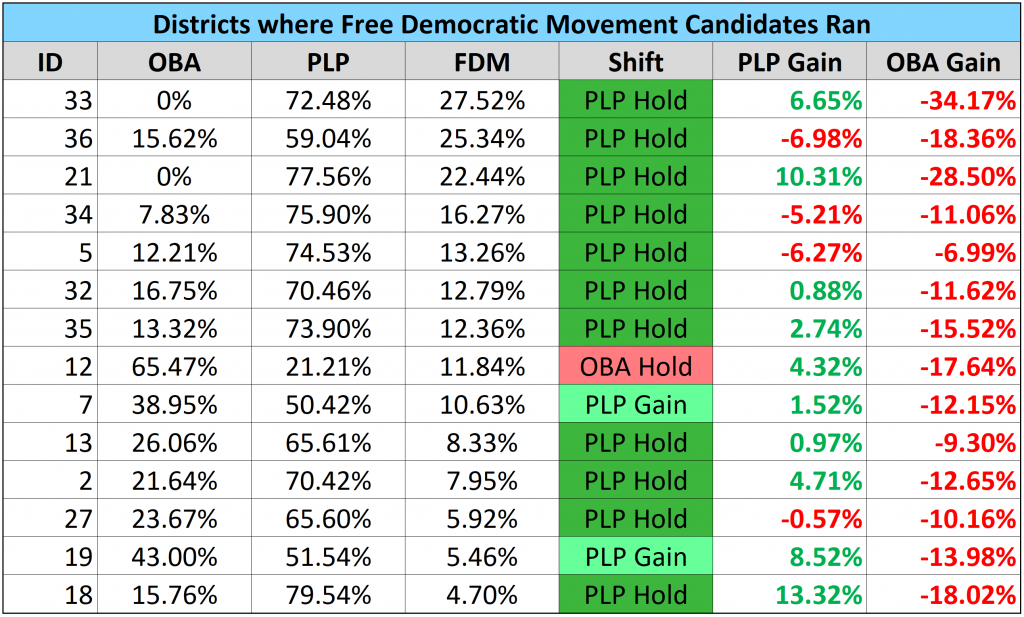

The FDM is not contesting every seat this election and their goal is to build up over several cycles and/or play kingmaker if the PLP doesn’t secure 19 seats to form a majority. The FDM is contesting 11 PLP seats and 3 OBA seats. The PLP seems to be largely worried about their west-end districts; where Marc Bean is from and more votes could be pulled from the PLP than in other areas.

Early voting is already underway and we should get results on election night or the next morning. I will update this with those results come in. This race could prove to be a major victory for the PLP – similar to the UBP’s landslide in 1985, or a major misstep by a ruling party. If the PLP does pull over a massive landslide and the FDM does largely take from the OBA, then its hard to argue the era of PLP dominance isn’t here.

Results Update

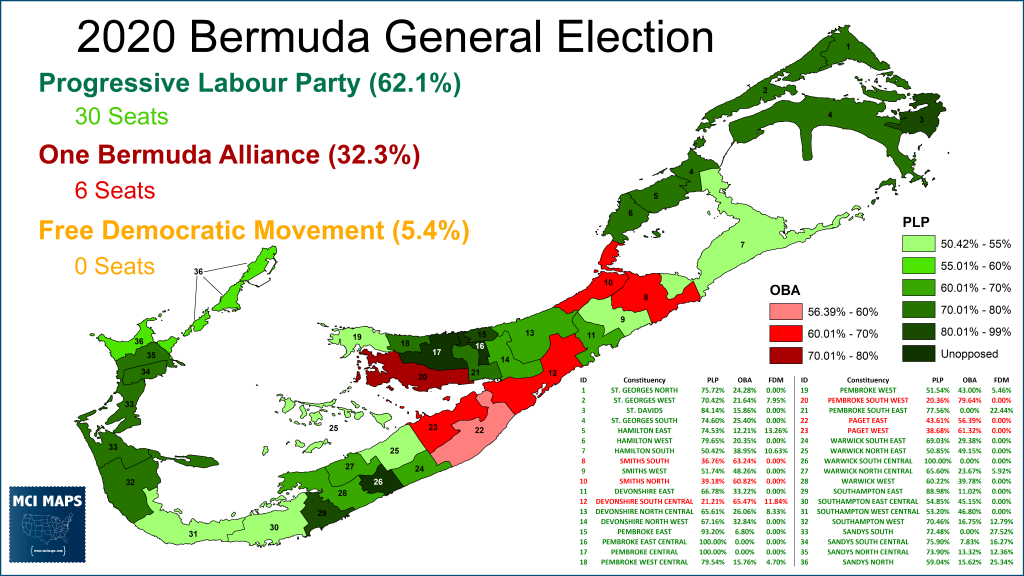

The election results have come in and the results are a landslide for the Progressive Labor Party. The PLP has gained 5 seats from the OBA (and held a seat they gained in a special election post-2017). The situation in parliament is now 30 PLP and 6 OBA. The FDM failed to take a single seat.

The PLP’s popular vote margin is even more stunning considering three of their best seats were unopposed (and hence no votes were counted). Had those seats been able to vote, the popular vote share would have likely passed 65%.

The Free Democratic Movement took far more from the OBA than it did from the PLP. In the districts it ran in, OBA lost votes while PLP actually saw gains. The main exception to this was district 36, where FDM leader Marc Bean (the former PLP leader) was running.

This will be the most lopsided parliament in the history of the territory. The era of PLP is for sure here.