On this day, January 10th, in 1861, Florida seceded from the union and joined the confederacy of southern states. This article aims to take a short look at Florida’s often-overlooked road toward secession.

Growing Secessionist Sentiment in Florida

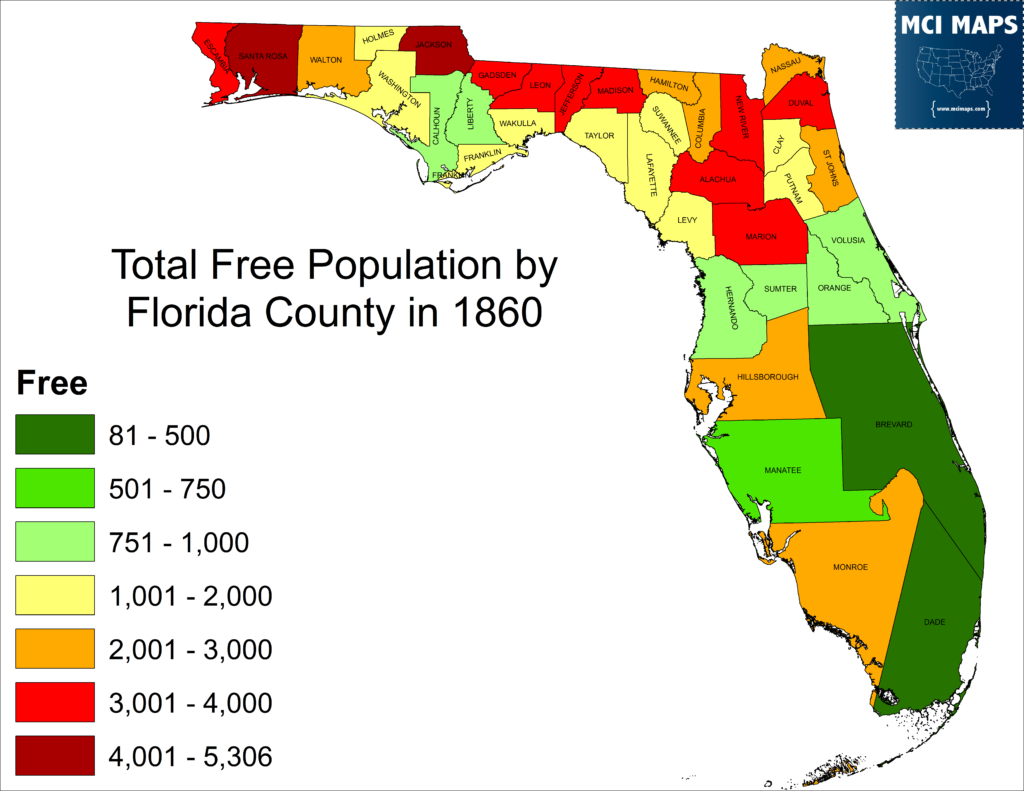

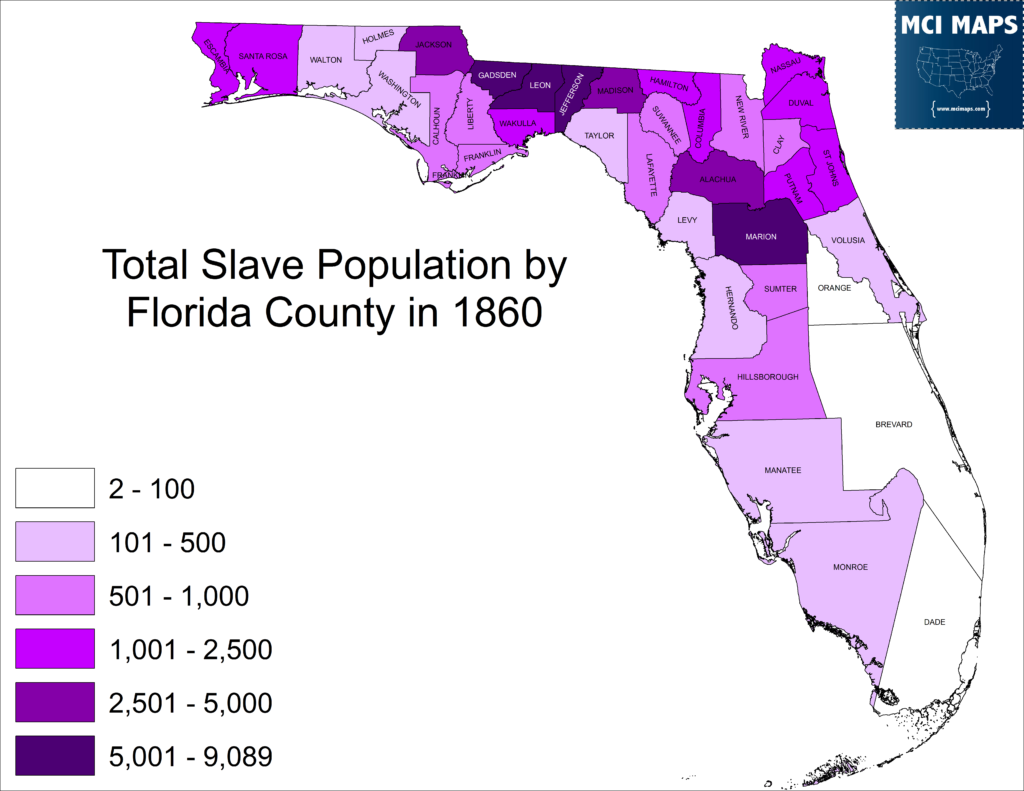

Like the rest of the nation, the 1950s was an extremely tense time in Florida politics. Growing sectionalism over the issue of slavery was driving a larger wedge between the North and South. Many southern politicians were agitated by concessions to the North in the Compromise of 1850 (letting California become a Free State). The growing abolitionist sentiment in the North made southern leaders nervous of attacks on the institution of slavery. At this time, Florida was fairly culturally similar to the rest of the American South. Most of the state’s growth came from South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. Voters in Florida saw themselves a southerners. The population of the state was heavily concentrated in the North and it had a large plantation network.

Like its southern neighbors, Florida was agitated with the growing abolitionist talk. Northern States’ refusal to send escaped slaves back (Violating the Fugitive Slave Act) further enraged southern politicians.

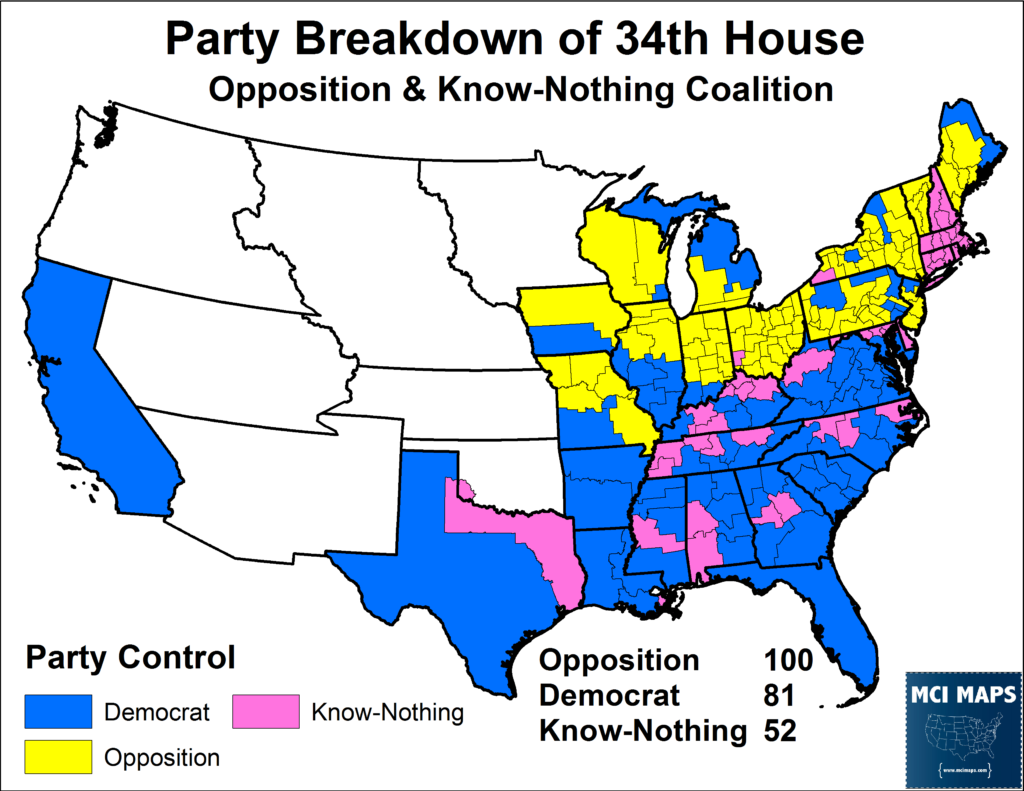

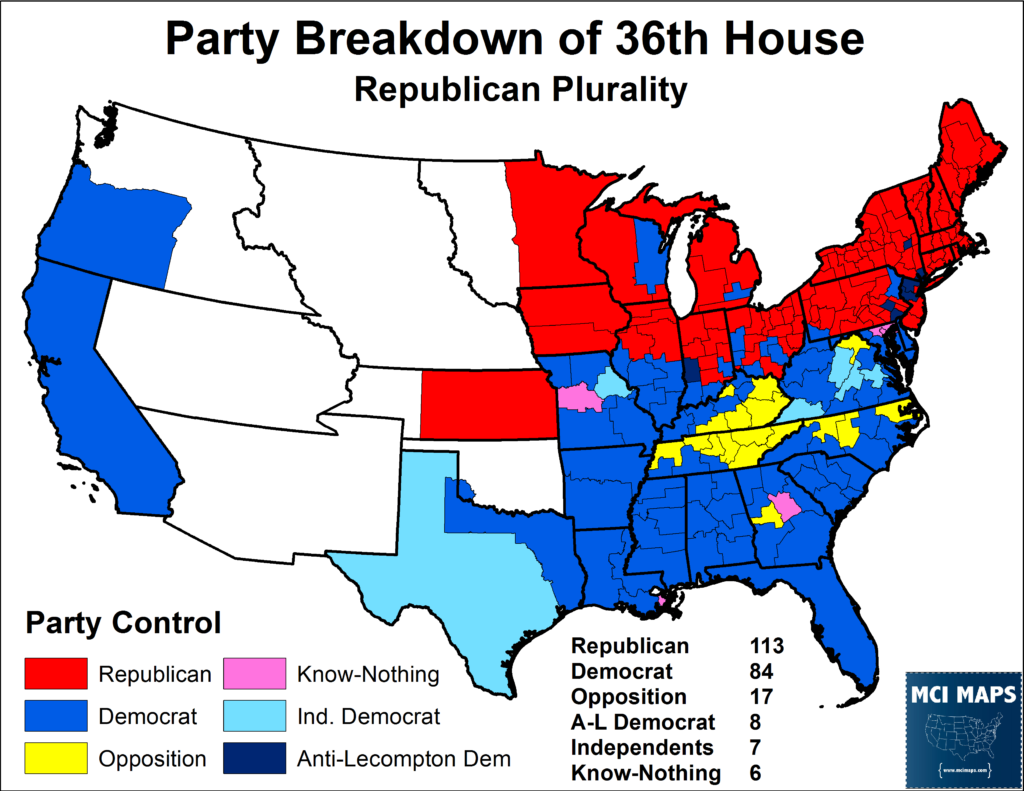

By 1854, Florida was solid Democratic state. The Whig Party had been torn apart by slavery and Democrats maintained strong majorities in the legislature and kept racking up modest but consistent wins statewide. Florida’s First Gubernatorial Election in 1845 produced a Democratic Governor. A Whig Governor was elected in 1848, but 1852 saw the Democrats reclaim the office and not relinquish it till the end of the war. Florida’s Democratic Governor in 1854, James E. Broome, echoed southern sentiment about the congressional results that year; which saw a Northern-backed coalition of Whigs/Republicans (called “Opposition”), and Know-Nothings win the House Majority.

Many of the newly elected representatives favored repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law and Kansas-Nebraska Act (which allowed slavery North of the 39th parallel). Neither repeal would happen. Democrats in the Florida, some of whom had advocated secession during the debate over the Comprise of 1850, were again beginning to clamor that secession might be needed if Northern hostility to slavery continued.

Pre-War Elections

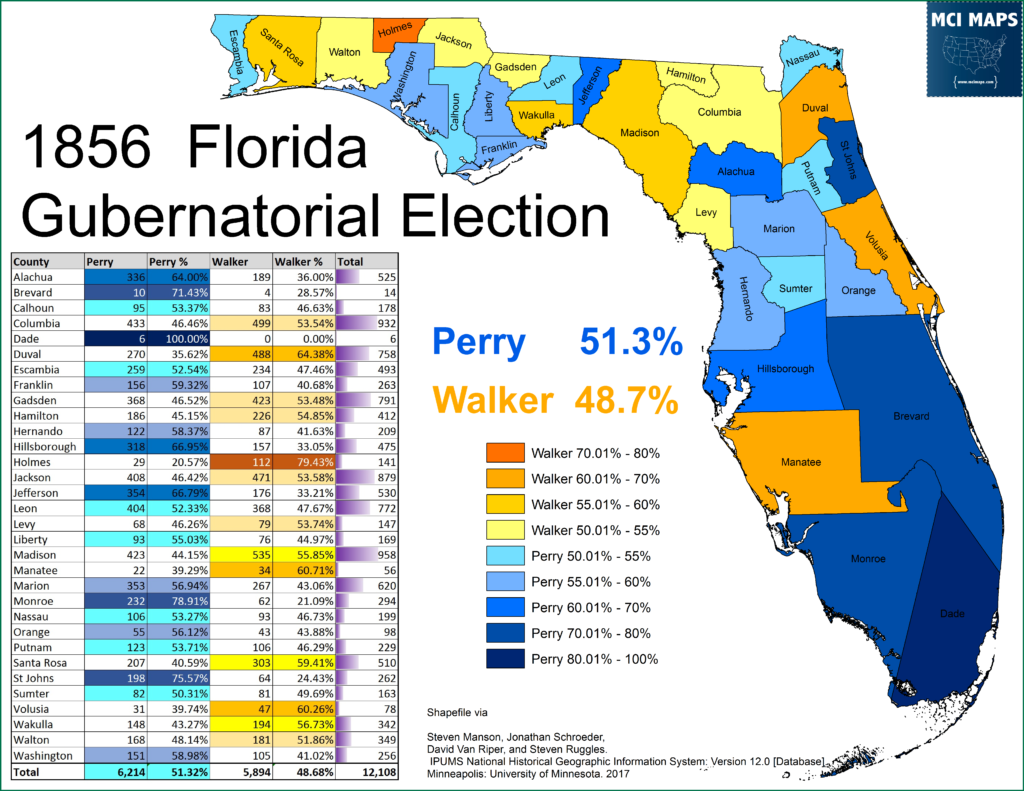

The 1856 Gubernatorial Election came at an especially tense time for the state. The race was held in October, one month before the Presidential Election (a common practice back then… and where the phrase “October Surprise” comes from). The Presidential race featured Democrat James Buchanan taking on Republican John Freemont and former Whig President Millard Fillmore. Freemont ran against slavery expanding in the territories. The prospect of a Republican win elevated secession calls if Freemont was elected. Democratic candidate Madison S. Perry argued for secession vs “black Republican” rule. David Walker, the Know-Nothing candidate, favored preserving the union and working toward concessions from the North on slavery. The results were a narrow win for Perry. A month later James Buchanan would win the Presidency and Florida (Freemont wasn’t even on the ballot).

The county results showed Walker strongest in the west and North. These counties, many made up of upper class southern planters, were more hesitant on secession; fearing it would disrupt business. The Democratic Party at this time in Florida has much more appeal with the rural and working class voters. The former Whigs, who’s support is similar to Walkers, were always more a party of middle and upper class voters. More details on this dynamic can be found here.

Perry was an ardent secessionist and believed that it was a matter of when, not if. He pushed for increasing the state militia and preparing for possible war or peaceful secession. The midterms of 1858 saw the Republican Party secure a majority of the US House, furthering Southern worries they would be shut out of power in DC.

Secessionist sentiment grew. In 1859, the Florida legislature passed a joint resolution pledging support to any southern states that seceded.

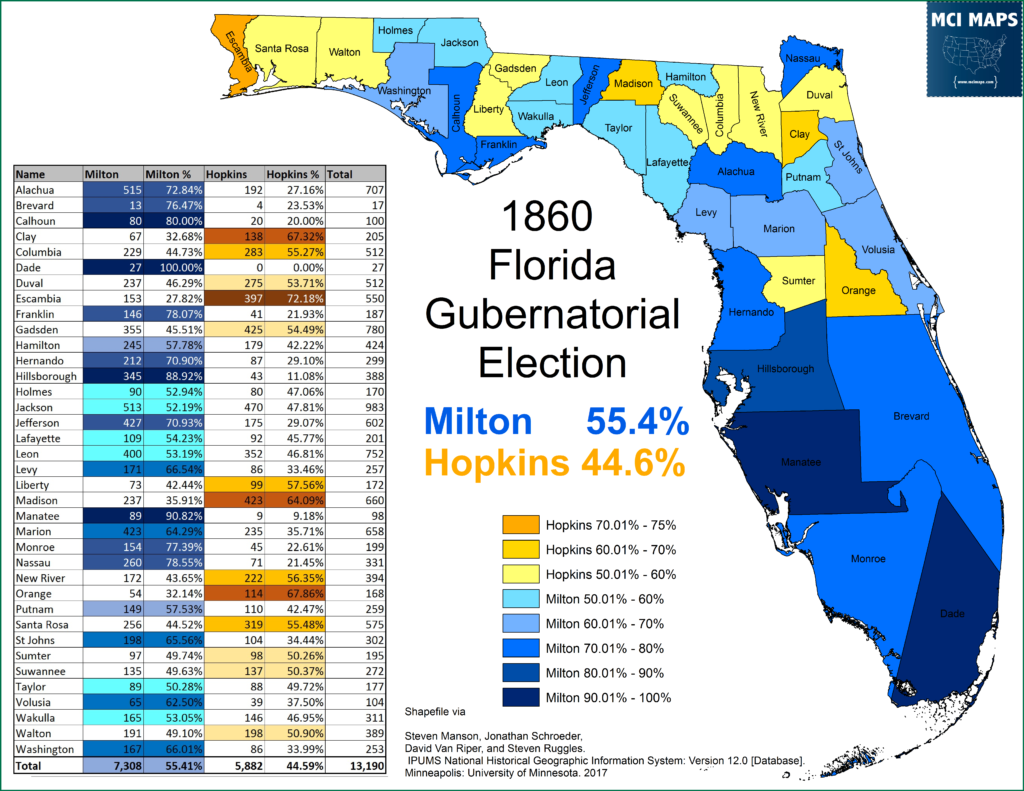

The 1860 Gubernatorial election was almost entirely based around the issue of secession. Lincoln was running for President and the chances of a Republican win was strong. Democratic candidate for Governor John Milton was, like Perry, a strong supporter of secession of the time called for it. Edward Hopkins ran under the “Constitutional Union” banner – a party that advocated unionism and compromise over slavery (while maintaining slavery in the south and some territorial expansion). Milton won the Governorship, ensuring Florida would have a pro-secession Governor during the war.

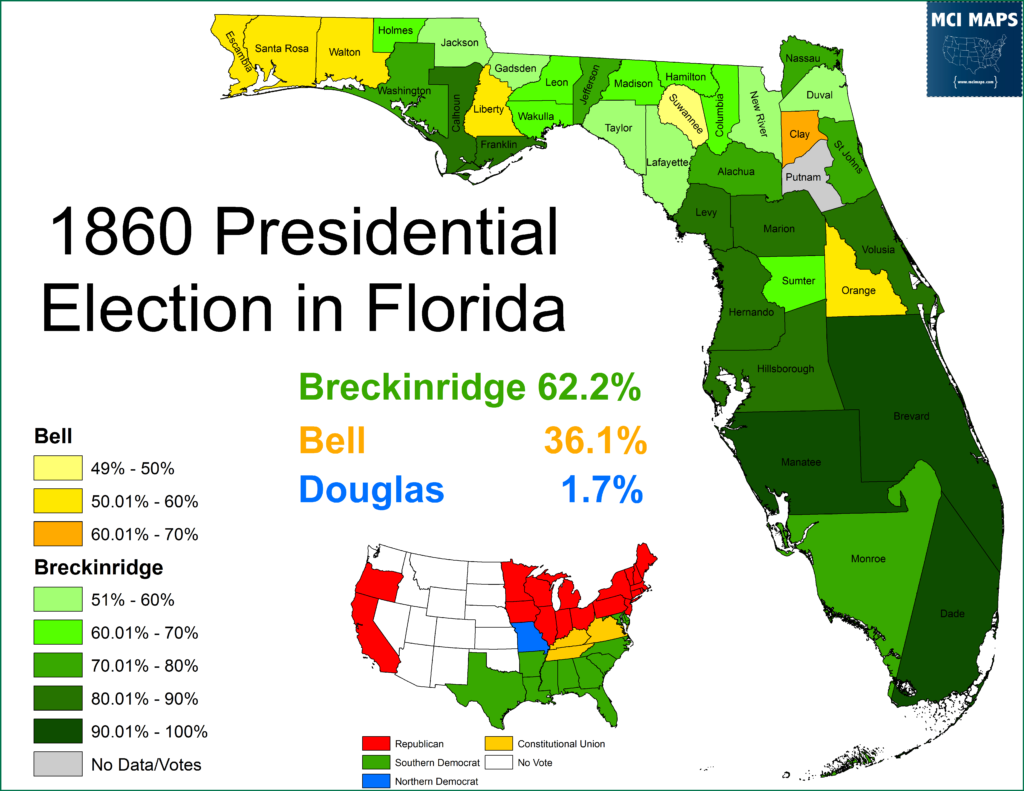

It was long believed the 1860 Democratic candidate for President would be Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas; the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. However. the national party had split when southern delegates demanded extreme positions in the platform. Southern slave-owners no longer supported Douglas’s “popular sovereignty” proposal. This proposal allowed residents of states/territories to vote on if a state should be slave or free and was the basis for the Kansas-Nebraska Act. However, in 1856 the Supreme Court announced the Dredd Scott Decision – which effectively struck down slavery bans in every state. Douglas supported states being able to ban slavery (like the North continued to do). Southern’s demanded the party take the position that slavery could not be restricted in the territories, regardless what the population wanted. When these demands were not met, the southern delegations bolted and set up their own convention. They nominated Vice President John Breckingridge of Kentucky; who during the campaign asserted that states had the right to secede.

The Presidential results saw an easy win for Breckingridge. The national Constitutional Union Party ran John Bell, who took a handful of counties in the state and secured over 30% of the vote. Douglas, representing the Northern Democrats, got scattered votes as most of his backers went to Bell. Lincoln wasn’t even on the ballot.

The national results saw a popular vote and electoral college win for Abraham Lincoln. With Lincoln’s election; secession sentiment kicked into high gear.

Florida’s Secession Convention

After the election of Lincoln, Governor Perry called for elections to be held for delegates to a convention on seceding from the union. The legislature adopted December 22nd as the date of the elections. The campaign was largely a fight between extreme secessionists, who favored immediately seceding, and cooperationists, who favored only leaving when other southern stated did as well. Many cooperationists hoped delay would force a compromise with the North and avoid possible war. Many prominent plantation owners were cooperationists, as they saw secession risking business. Those with fewer slaves, or pro-slave voters without slaves, were much more stringent secessionists. Even those without slaves, often due to income, desired to one day be slave owners. In addition, white workers feared the competition freedmen would present in the workforce.

Exhaustive research has not turned up actual results from the these races. Scholarly reports have cited different first-hand accounts but all acknowledge the difficulty in tracking down results. They almost surely exist but at the time of this writing I could not find them. It is estimated that the strict secessionist slates won around 60-65% of the popular vote and cooperationists got around 35-40%. Cooperationist, and scattered unionist, support was strongest in the western counties and counties that were former Whig and Know-Nothing strongholds. Secessionists were strongest in Democratic counties.

The makeup of the delegation was clear when John McGehee, a long-time rabid secessionist from Madison County, was elected President of the convention. The first day of the convention was January 3rd. Cooperationists knew they were outnumbered. The state apparatus favored secession and delegations from Alabama and South Carolina were sent to assure the delegates their secession was the right course of action (and that Alabama’s would be coming soon). By this point South Carolina had seceded and Mississippi was days away. Debate raged in Alabama and Georgia. Cooperationists argued they should wait till Alabama and Georgia acted before seceding themselves.

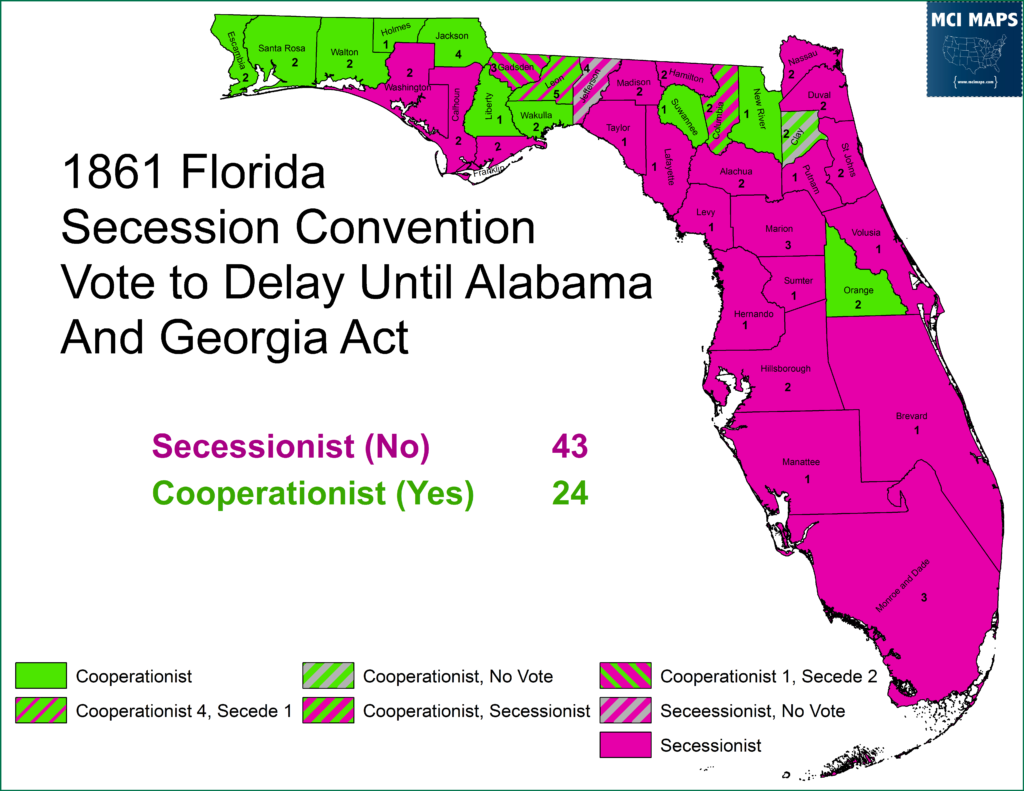

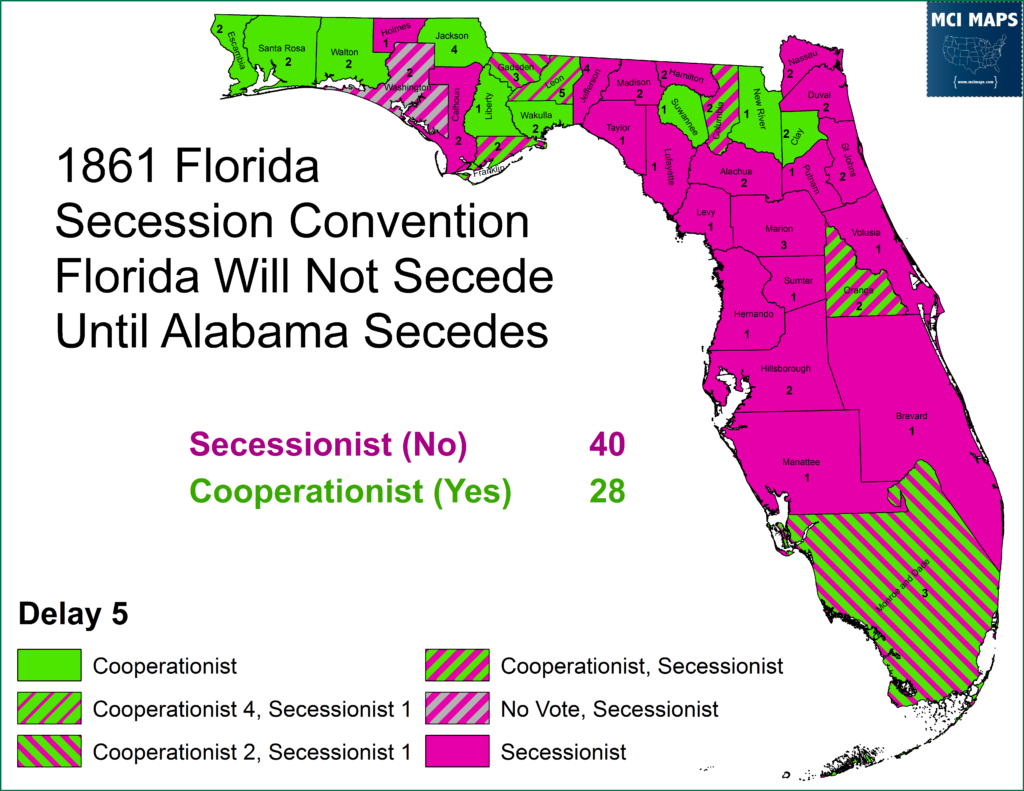

The first effort to delay came in the 3rd day of the convention when the cooperationists tried to attach an amendment to a resolution stating Florida had a right to secede if it chose to. The amendment changed language to argue Florida would hold off on secession to see if Alabama and Georgia would indeed secede. The amendment failed.

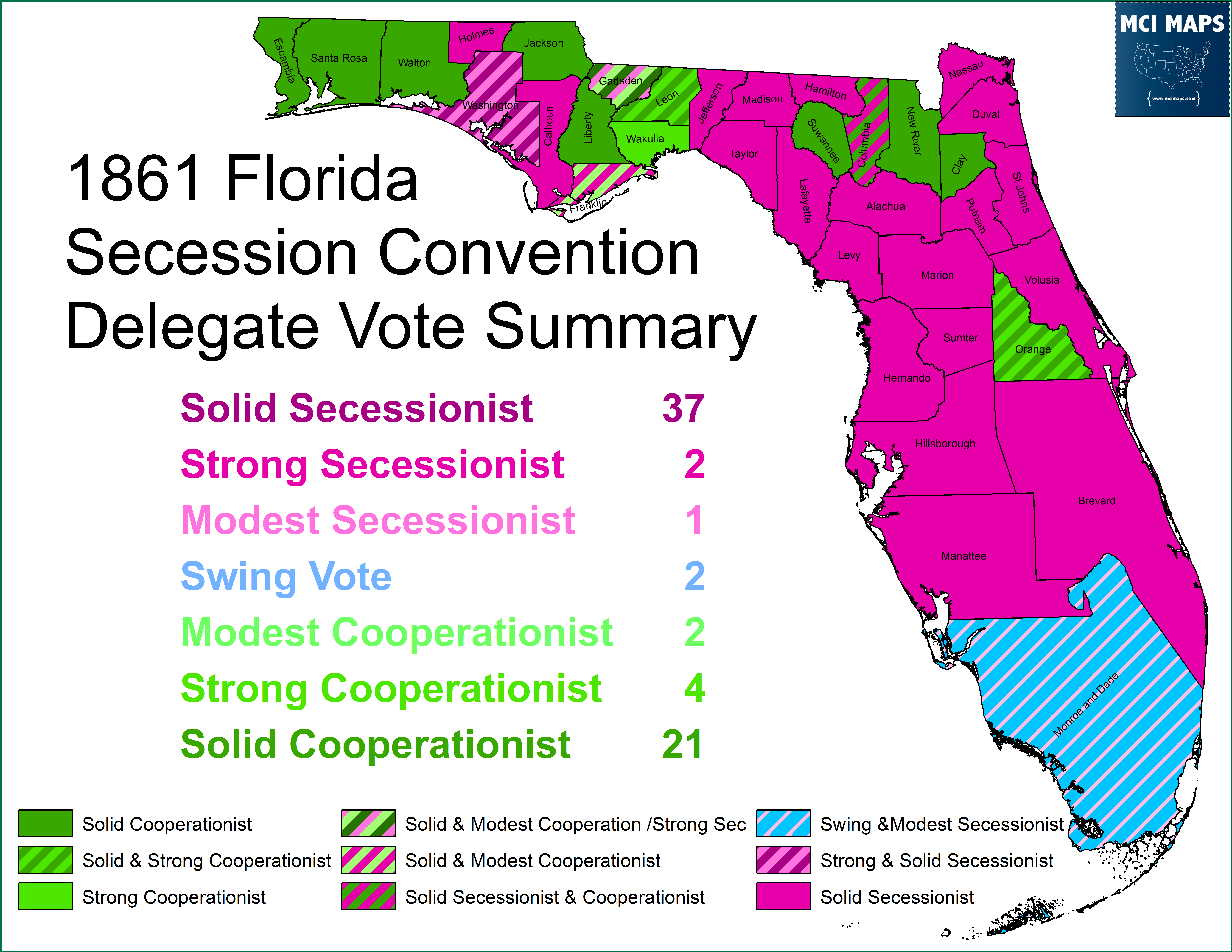

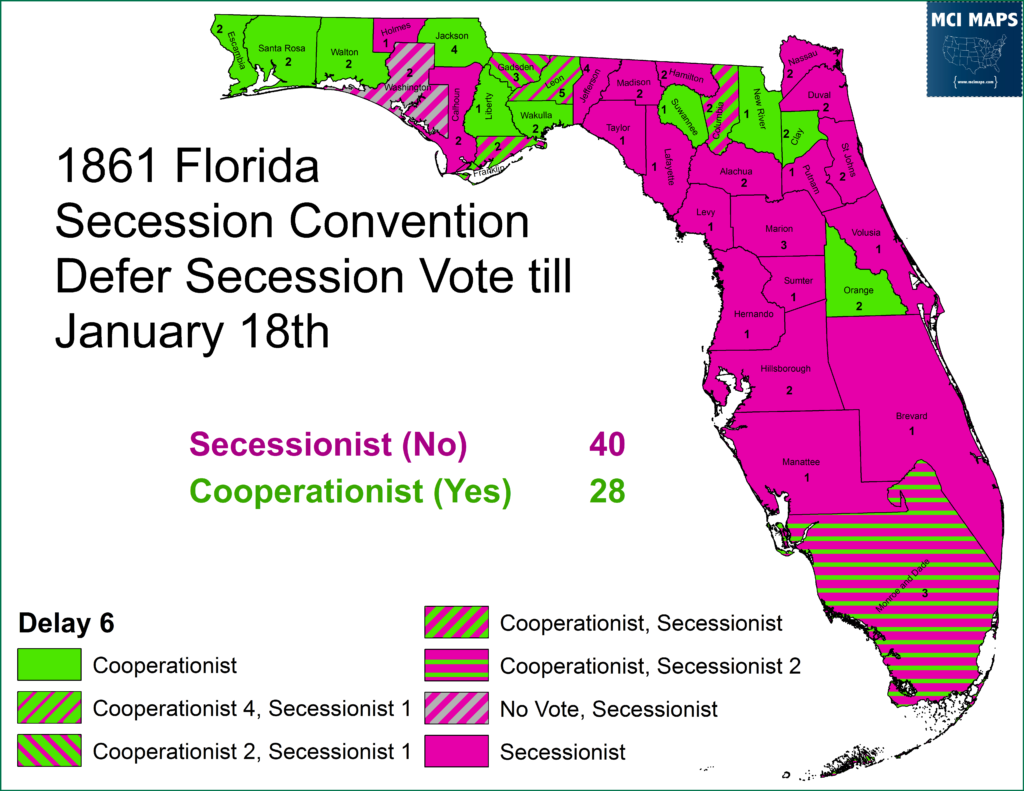

The maps show the number of delegates in each county and what “camp” each vote fell into. Counties had different delegate numbers depending on population and some State Senate districts sent delegations as well. If a county is colored whole, that means all its delegates voted the same. As the map shows, many of the former Whig, Know-Nothing, and Constitutional Union counties saw their delegates support the amendment.

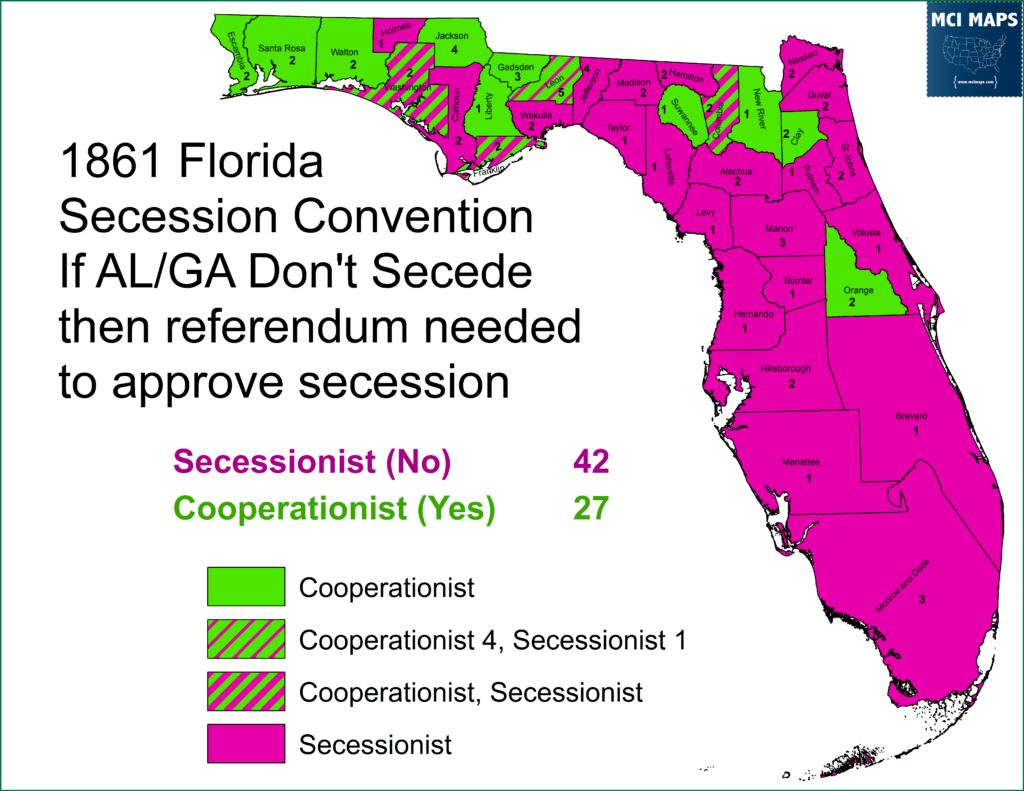

The convention broke into committees, heard speeches and delegates began drafting a proposed ordinance of secession. Cooperationists kept trying to insert amend amendments to delay actions. On the fifth day they introduced several amendments. The first said that if Alabama and Georgia did not secede, then a popular referendum would be needed before Florida seceded. The vote failed.

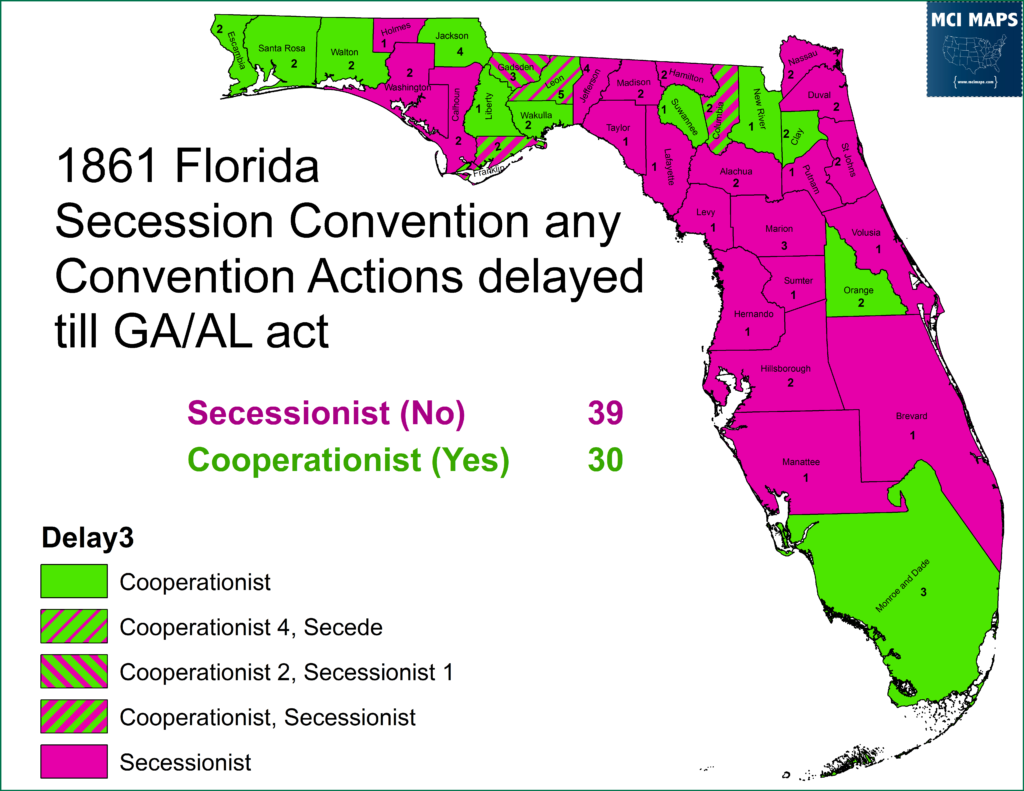

The next proposal delayed any action by the convention until Alabama and Georgia acted on the issue of secession. The measure was also rejected by a similar margin.

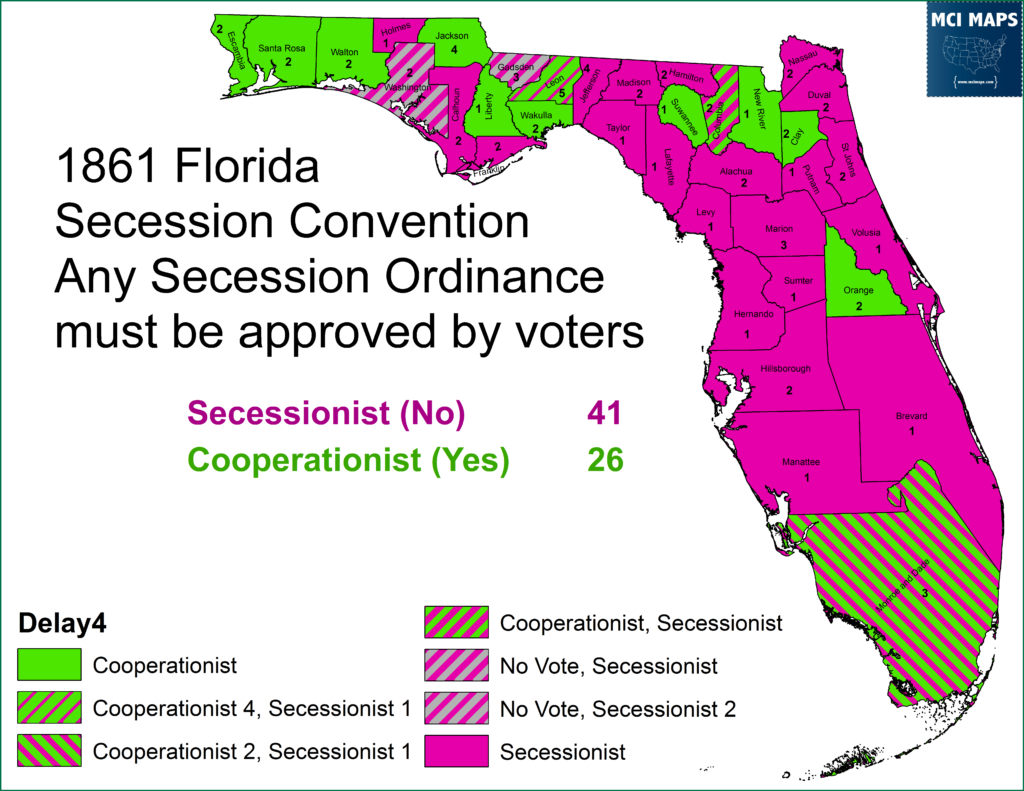

The next proposal, a more stringent cooperationist measure, said secession could not happen until the voters approved it; regardless what Alabama and Georgia did. This lost by a larger margin.

The next measure said the convention would not vote on secession until they heard from Alabama on its secession plans. This, like the others, fell.

The final amendment offered delayed the convention from voting on the secession ordinance until January 18th. This measure failed as well.

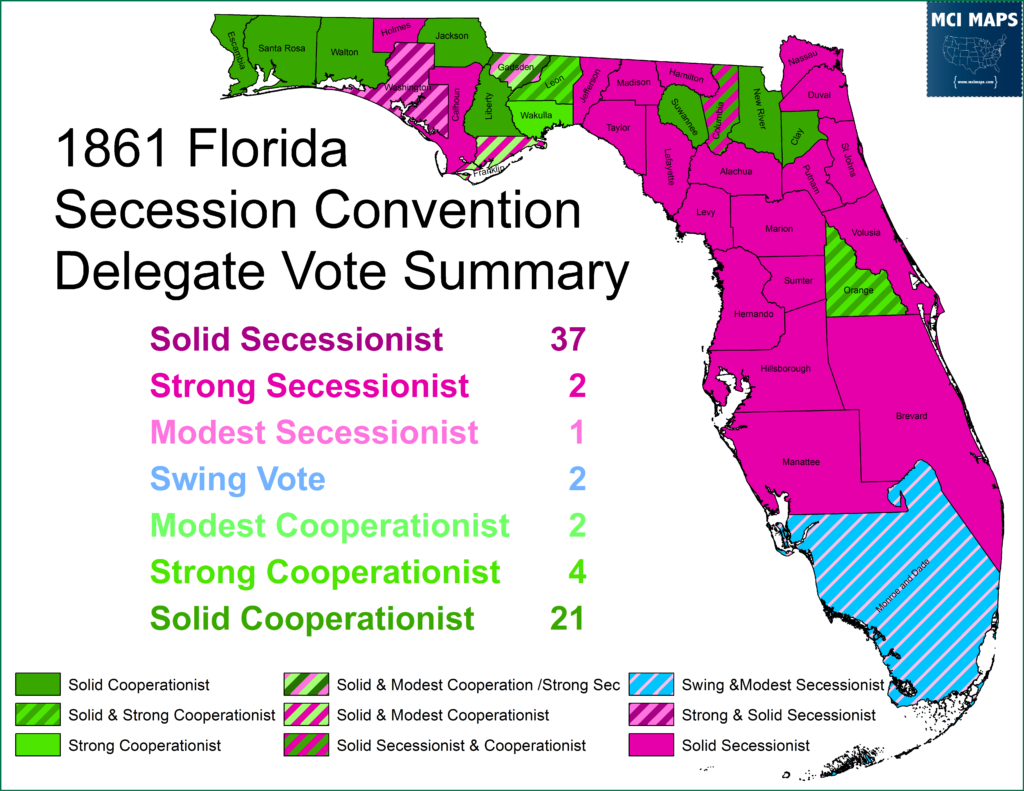

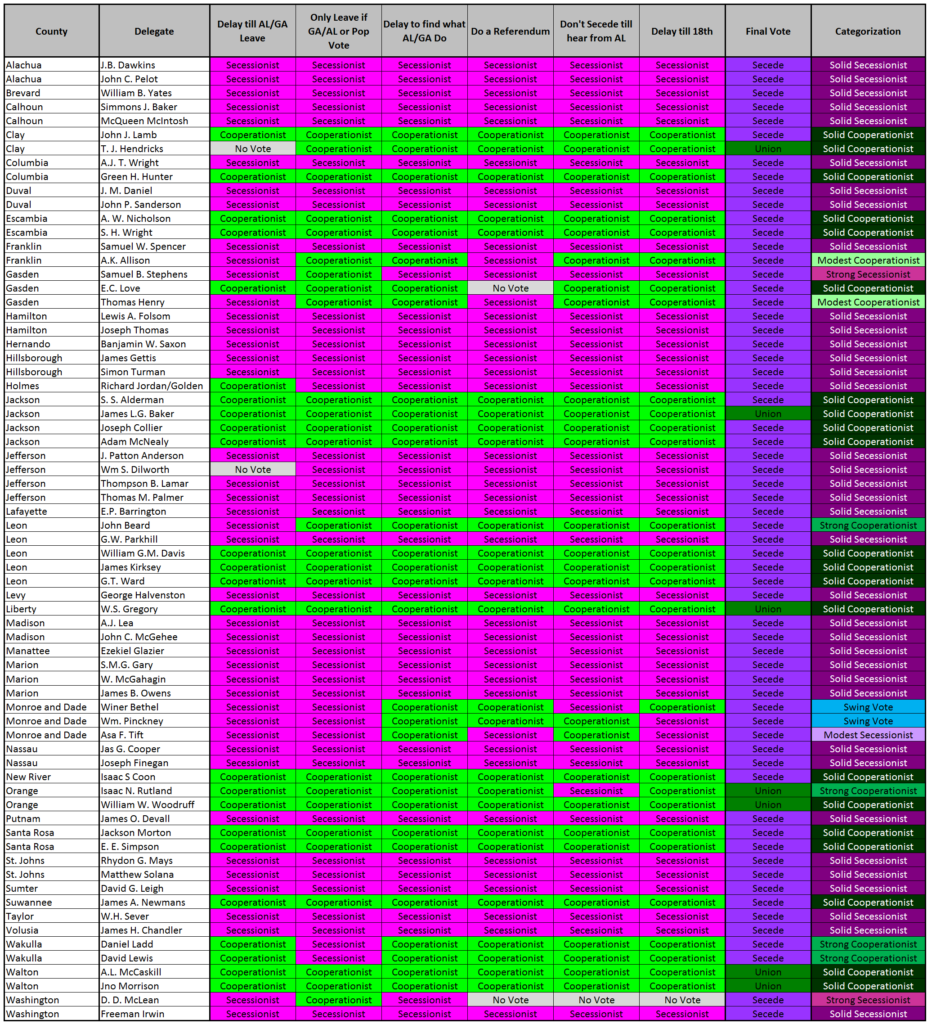

The six votes the cooperationists push show a clear pattern in terms of county voting. Many cooperationists voted for every proposition, though there was some deviation. Using these six votes I categorized each delegation.

Solid Cooperationist — Supported every measure when voting (not voting didn’t count against them)

Strong Cooperationist — Vote against only one measure

Modest Cooperationist — Voted against at two measures

Swing – Split 3/3 on the measures

Modest Secessionist — Voted for at two measures

Strong Secessionist — Vote for one measure

Solid Secessionist — Didn’t vote for any measure

The results are below.

The map shows a pattern similar to past elections. The west and northern plantation counties were much more wary of secession while more rural and growing areas were much more in favor.

Map Note: The Holmes delegate during the first vote (cooperation side) was removed when the election showed his opponent had won. The replacement voted secessionist across the board.. so I labeled that seat “solid secessionist.”

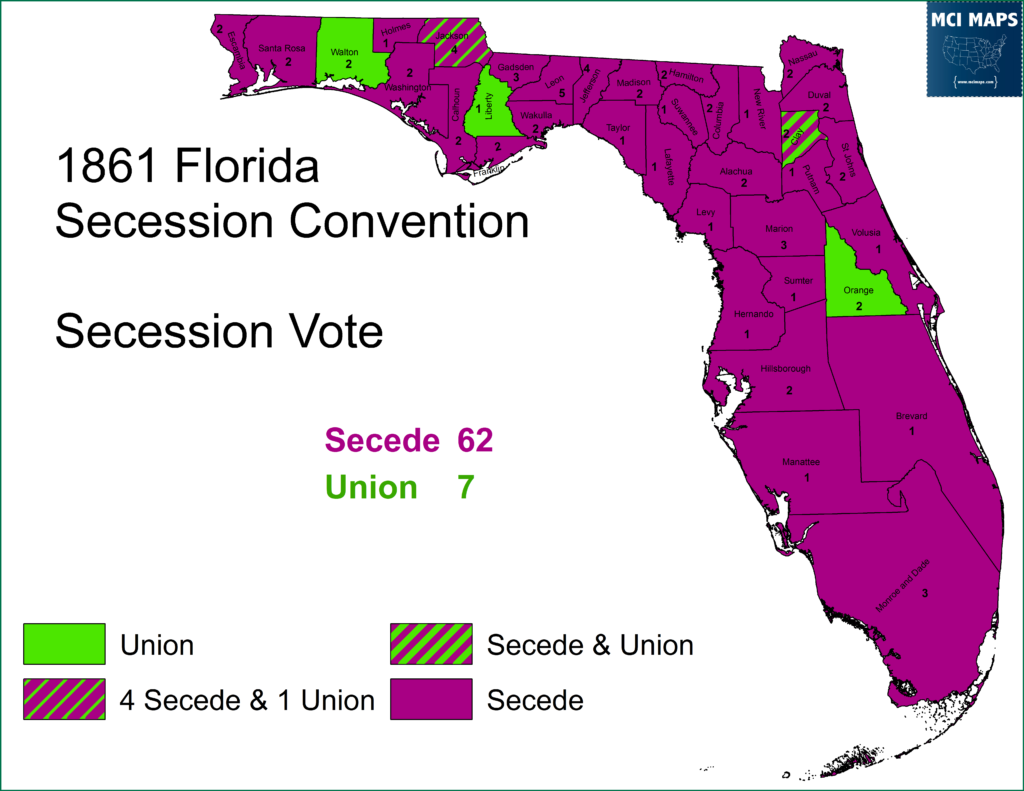

With all cooperationist measures soundly defeated, it was clear secession was imminent. The convention adjourned for the day. On the sixth day, the convention took up an ordinance of secession for an up or down vote. Many cooperationists, resigned to the fate of Florida, voted to secede as an act of solidarity. Only a handful of hard unionists voted no.

Florida, therefor, officially seceded on January 10th, 1861.

Conclusions

Florida would not be the site of ferocious battles you read about in history books. The Battle of Natural Bridge is likely the most famous, and it pales in comparison to major fights. Florida was more a source of supplies than it was a battlefield. Tallahassee remains the only Confederate Capital not to be invaded (obviously due to its distance). When union victory was assured, Governor Milton wrote to the legislature that “death is preferable to reunion” and committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

—- We might be the only state to have a sitting Governor kill himself. I couldn’t find any other examples.

Federal troops would enter the capital on May 19th, 1865 (six days after the war ended) and take control of the state government. Florida would go through reconstruction like its fellow southern states and eventually devolve into a Jim Crow state through much of the late 19th and early/mid 20th century. The state’s rapid population grow via migration has left only a small share of its populace with ancestors dating back to Florida at this time.

And, yes, we still have plenty of people who still try to claim the war wasn’t about slavery.

–

Note

Below are the convention votes I highlighted by delegates. You can click the image for a larger view.