Last week, I examined the push to get redistricting reform enshrined in Florida’s Constitution. This effort culminated in 2010, with the passage of the Fair Districts Amendments. The measures banned partisan gerrymandering and set up tiers of criteria for drawing of districts.

The measures set up two tiers for redistricting regulation in Florida.

- Tier 1 – Lines cannot be drawn to favor or disfavor an incumbent or party. Districts also cannot be drawn to diminish the ability of racial or language minorities to elect candidates of their choosing. Districts must be made up of contiguous territory.

- Tier 2 – Districts must be compact, as equal in population as possible, and honor administrative boundaries when possible

The Fair District Amendments were vehemently opposed by the Republican leaders in Florida. This article will cover the initial clash between the GOP and the Fair Districts Amendments.

2011 Efforts to Stop Reform

With the passage of the Fair Districts Amendments, there was a clear effort by opponents of the law to circumvent the measures. This began as early as 2011.

Lawsuits

In my article on the Fair Districts campaign, I talked about opposition to the measures that came from Republican Congressman Mario Diaz-Balart and Democratic Congresswoman Corrine Brown. Brown’s opposition to the fair districts amendments was well documented; with Democratic activists largely viewing her opposition as an act of self-preservation (as she tried to maintain her JAX to Orlando district). Both members filed a lawsuit seeking to strike down the amendments, arguing it would hurt minority voting strength. House Speaker Dean Cannon joined the lawsuit; spending millions in taxpayer money to fight the measures. In September, a federal judge rejected the lawsuit and affirmed the Fair Districts Amendments. Cannon kept the House involved in the ultimately-unsuccessful appeals.

Department of Justice Approval-Nonsense

Rick Scott waded into the redistricting war as well when he opted to delay submitting the Fair Districts Amendments to the Department of Justice for review/approval. At the time, Florida had to get DOJ approval for voting/redistricting changes. Outgoing Governor Charlie Crist submitted the amendments to the DOJ for approval in December of 2010. However, just three days after taking office, Governor Rick Scott pulled the request for review. Scott insisted this was not to delay redistricting, but never offered a clear reason for the move. Scott would eventually declare he legally was not the one to submit the measures to the DOJ, resulting in the House and Senate doing it. As a result, Speaker Dean Cannon and Senate President Mike Haridopolos submitted a request for approval. Their memo to the DOJ had an add-on interpretation….

To avoid retrogression in the position of racial minorities, the Amendments must be understood to preserve without change the Legislature‘s prior ability to construct effective minority districts. Moreover, the Voting Rights Provisions ensure that the Amendments in no way constrain the Legislature‘s discretion to preserve or enhance minority voting strength, and permit any practices or considerations that might be instrumental to that important purpose. In promoting minority voting strength, the Legislature may continue to employ whatever means were previously at its disposal.

Cannon-Haridopolos note in memo to JOJ

The implication was clear, the Florida GOP was eager to continue its practice of packing minority voters; as it had in 2002. In June of 2011, without agreeing to the legislative interpretation, the amendments were approved by the DOJ. The whole debacle did nothing but spark ill-will on all sides.

2011-2012 Mapping Process

The legal and political drama of 2011 revealed a legislature and Governor who did not like the restrictions that were being placed on them. The go-to defense of their opposition was to frame themselves as the great protectors of minority voting interests. Nevertheless, as the lawsuits went through the courts, the legislature began its redistricting process.

Mapping Software and Political Data/Functional Analysis

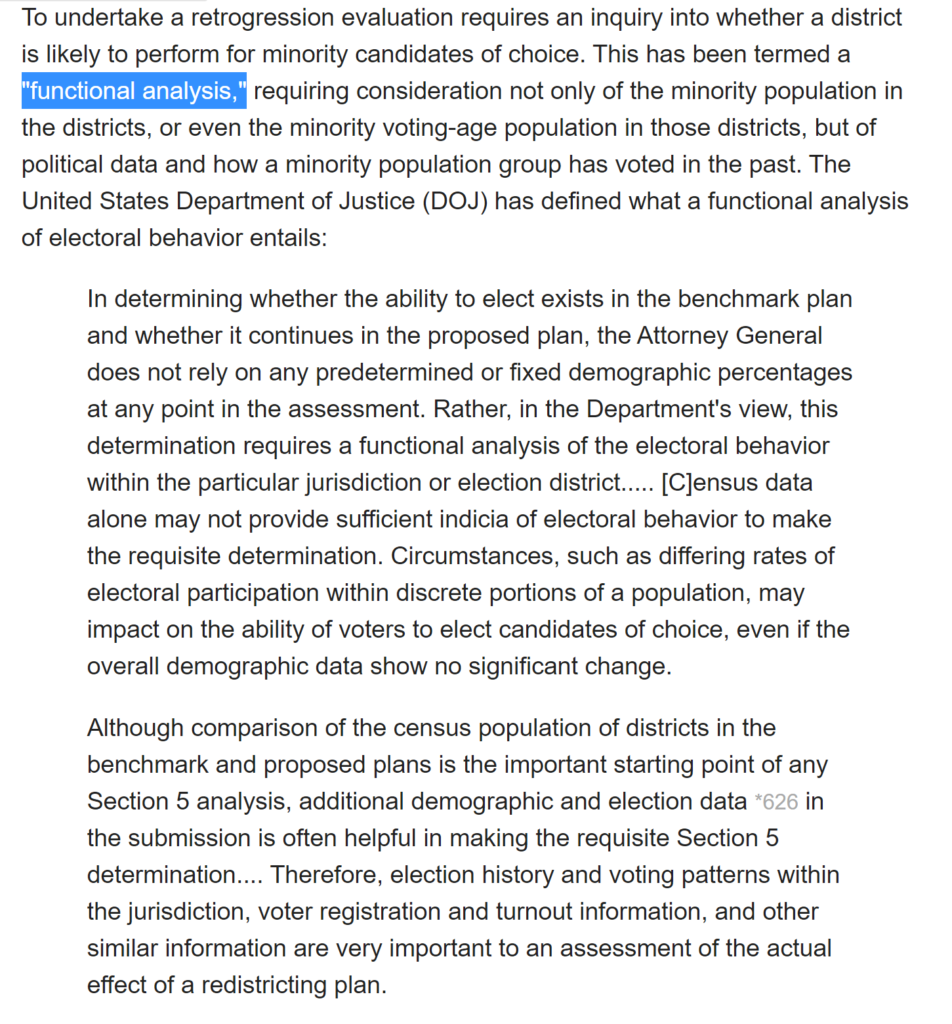

Florida got its census data in March of 2011, and a public portal was made available for the public to submit and draw maps. The mapping software was fairly user-friendly and didn’t take much time to get accustomed to. The software included all relevant census and American Community Survey data. In addition, political data was included. The inclusion of political data was a necessary but tricky considering the Fair Districts Amendments. While the amendments banned drawing districts to benefit a party; political data was needed for ensuring minority districts. Many minority districts, especially African-American seats, were under 50% African-American. A common method to determine if a district was a viable minority-performing seat was known as Functional Analysis. This process involved looking at how a district voted in general elections, and then looking at the demographic makeup of the primary for the dominant party. If a 45% African-American district was shown to back Obama with 60%+ of the vote, and had a 65% Democratic primary, then it gave African-Americans the opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice.

Functional Analysis was being used in Florida as far back as the 1990s. At the time, Hispanic districts were largely viewed as needing well over 60% Hispanic voting-age-population (VAP) due to large non-citizen shares of the population. African-Americans largely did not require such a large share of a district. Functional Analysis was often used to confirm how census data matched voting reality. Political data was needed to run this analysis, and was utilized by lawmakers in both parties. The Florida Supreme court would affirm the need to use political data when it passed its rulings on the 2012 legislative districts.

The major conflict in 2012 over minority districts, namely African-American districts, was how high the African-American VAP should be. In 2002, Republican had supercharged multiple African-American plurality seats and turned them into majority-black districts.

Using the online mapping software, over 150 proposals were submitted by the public.

Hearings

Beginning in the summer of 2011, hearings were held across the state of Florida. Members of the redistricting committees travelled across Florida, where residents could discuss how they preferred the district lines went through their communities. These hearings were videotaped and archived for viewing Florida’s redistricting website.

Initial 2012 Maps

The legislature passed preliminary Congressional, State Senate, and State House maps in February of 2012. In the case of the state legislative maps, each chamber agreed to draw the lines for its own body. The combined maps would be passed together. The legislative maps were drawn by Republicans, passing on a party-line vote in the house but with multiple Democratic votes in the Senate. The Senate vote reflected a more collegial nature in the chamber, while the House was ruled by arch-conservative Dean Cannon. However, many Democratic Senators angered activists with their backing of the maps. Two Republicans, Fasano and Dockery (who had bad relationships with the growing Conservative wing of the GOP) rejected the maps. While the NAACP backed the maps, the Senate’s black caucus was divided on the maps. Gibson, Siplin and Bullard backed them; while Joyner, Smith, and Braynon did not. In the House, all members of the black caucus voted no to both sets of maps.

Both chambers were able to come to an easy agreement on the Congressional map (less drama than 2002). The state was getting TWO new Congressional seats. Maps were initially passed in February of 2012. The roll calls for this plan was largely the same, with a party-line vote in the house and more bipartisan vote in the senate.

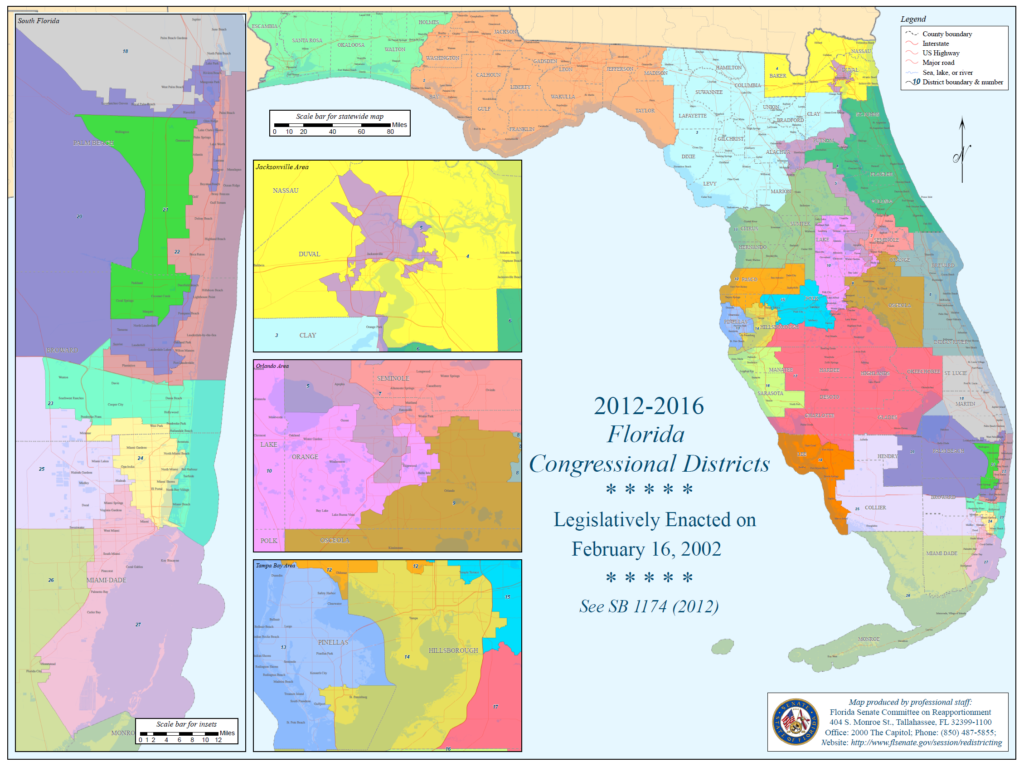

The Congressional map that was passed is below.

The district retained the 3 African-American and 3 Hispanic districts from 2012. In addition, a new plurality-Hispanic district was formed in the Orlando region – district 9. This reflected massive growth in the Orlando area, specially among the growing Puerto Rican population.

- FL-05: 49.0% Black VAP

- FL-20: 48.9% Black VAP

- FL-24: 51.7% Black VAP

- FL-9: 39.1% Hispanic VAP

- FL-25: 68.9% Hispanic VAP

- FL-26: 67.4% Hispanic VAP

- FL-27: 72.8% Hispanic VAP

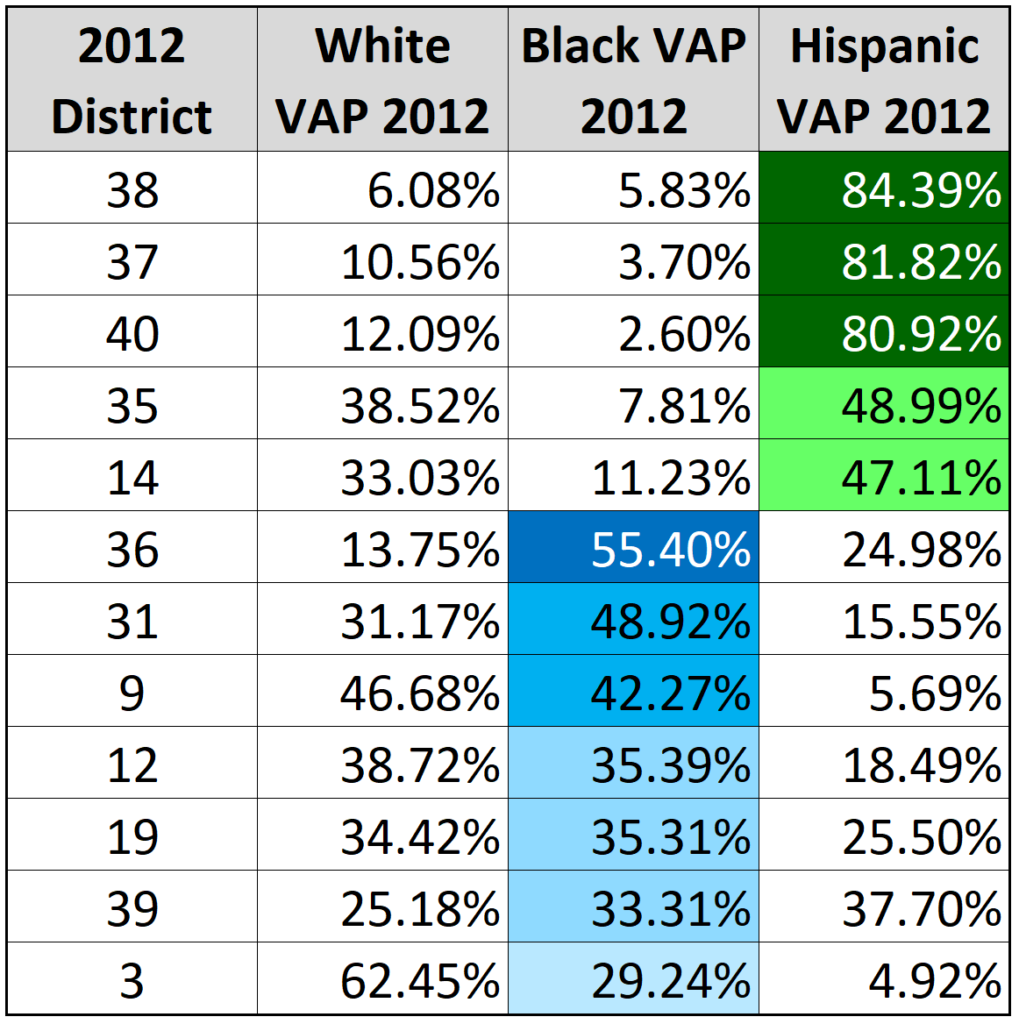

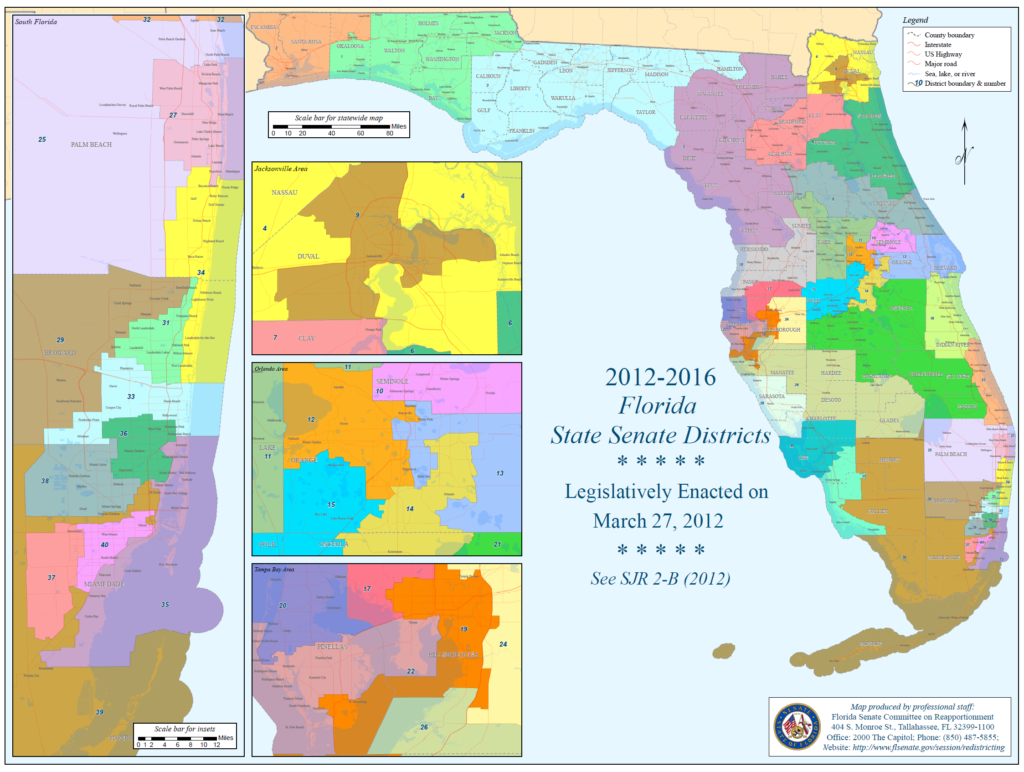

The State Senate map can be seen below.

The map continued multiple minority districts and saw the creation of a new plurality Hispanic district in the Orlando region.

The State Senate, unlike the house, would not use a functional analysis to confirm the minority opportunities of districts. Instead they relied on VAP data. This would be subject to criticism from the Florida Supreme Court.

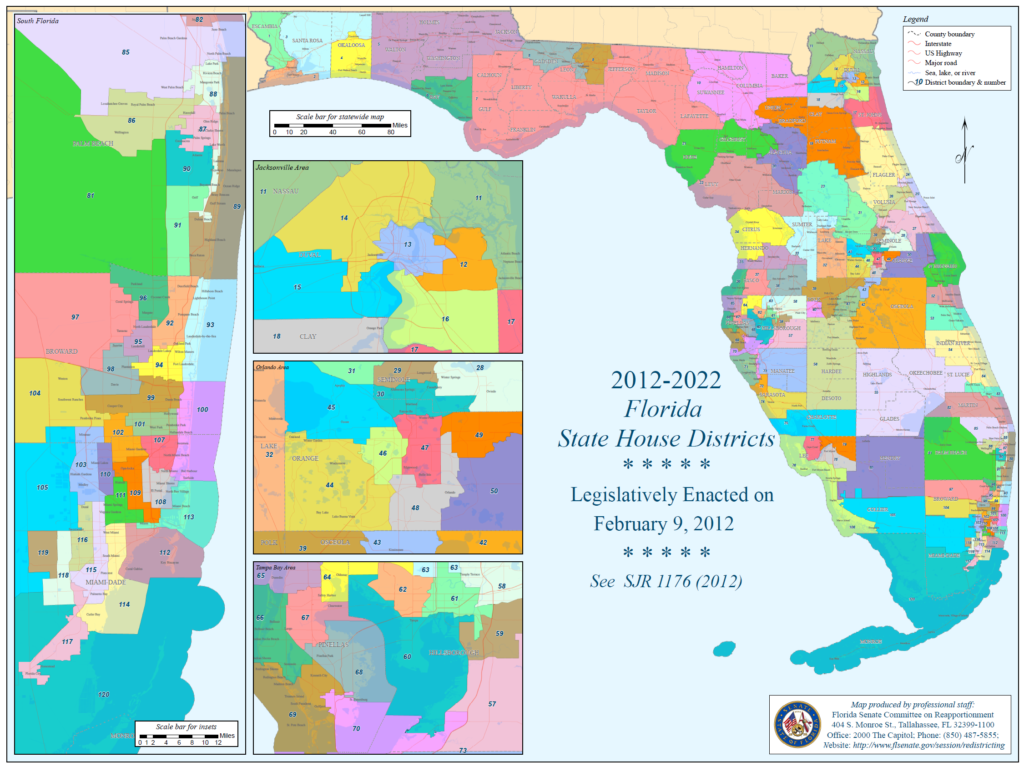

The State house plan can be seen below.

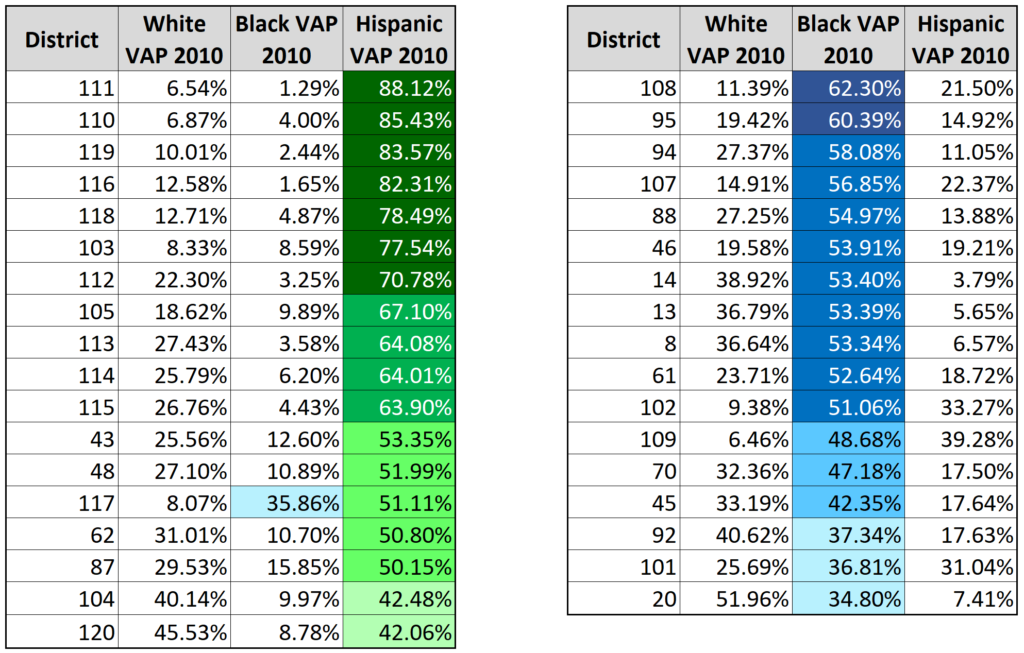

The racial makeup is below. As discussed before, Hispanic VAP numbers in Miami-Dade needed to be super-majority to contend with the sizeable non-citizenship population in the community. Functional analysis was utilized to confirm the voting makeup of the electorate. For example, while HD-117 was majority Hispanic, it was actually an African-American district in terms of voting (and would have an African-American representative). Meanwhile, HD-48 and HD-43, located in Orlando metro zone, did perform as Hispanic districts. The Orlando area, home to a growing Puerto Rican population, had a smaller non-citizen population. Through lower Hispanic turnout was an issue.

In 2002, many plurality African-American districts were moved to majority African-American. The 2012 House plan largely continued this practice. Meanwhile, districts like HD-20 or HD-101 performed as African-American districts thanks to being heavily Democratic and having Democratic primaries with a plurality or majority African-American vote. An example of the Functional Analysis at play.

Florida Supreme Court Review

Per the Florida Constitution, the Supreme Court of FL had to review and sign-off on the legislative maps (but not Congress). Multiple districts in both maps were being challenged. Some were challenged by a coalition of plaintiffs made up of the Fair Districts organization. Others were being challenged by the Florida Democratic Party.

The court used the review as an opportunity to review the Fair Districts amendments and set the standards for redistricting going forward.

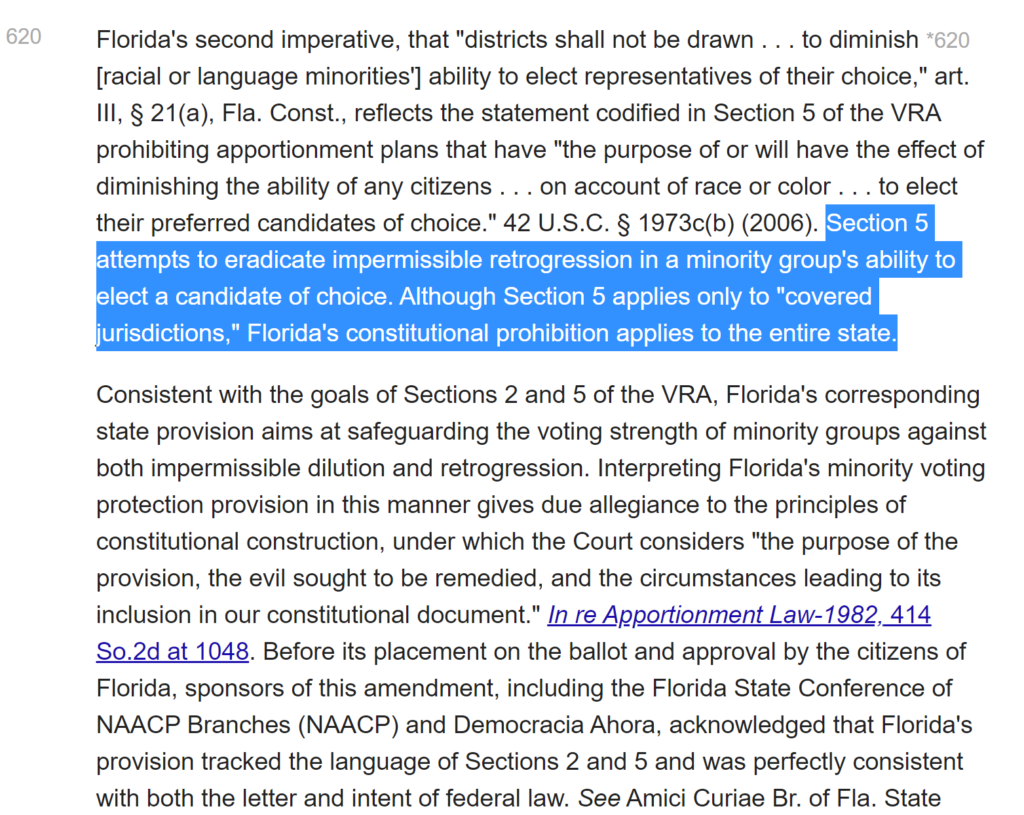

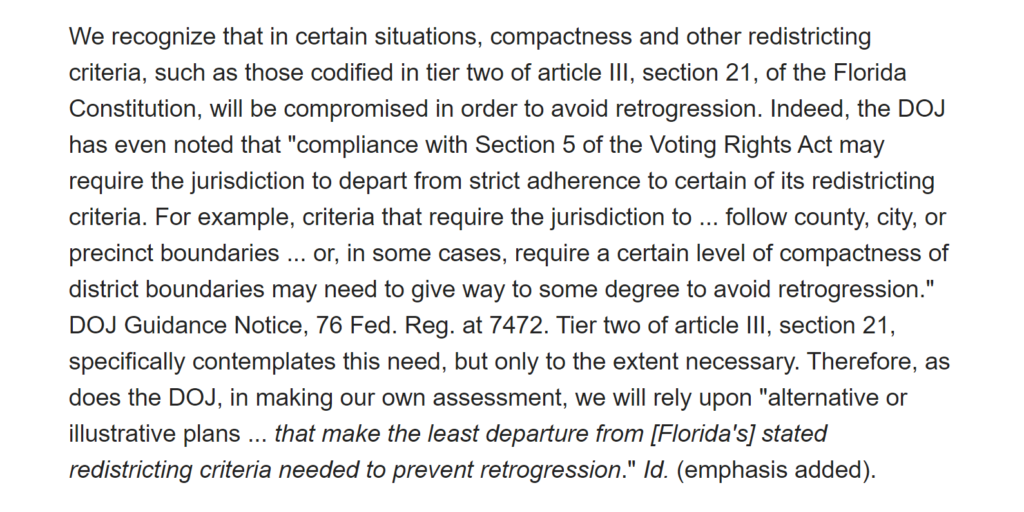

The court examined the issue of retrogression in great detail. As the court pointed out, the Fair Districts Amendments incorporated language from Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. This language creates the standard against retrogression (aka a reduction in the ability of minority voters to elect candidates of their choosing). This created a universal, state-wide standard protecting minority-performing districts from being eliminated. This meant districts that perform as minority seats were protected. 50%+ VAP was/is not needed.

The court again affirmed the use of political data for the purposes of functional analysis.

The court opinion; which upheld the house plan but invalidated the senate plan, went into detail on its interpretation of the Fair District Amendments. The court went into detail in discussing the balance of compactness with racial minority voting rights and the ability of the court to judge political intent. The full opinion can be found here. For this article, I will go over some of the highlights. The opinion is full of very valuable information, and I consider it critical reading for anyone who wants to fantasy-redistrict this cycle.

State House Signed Off

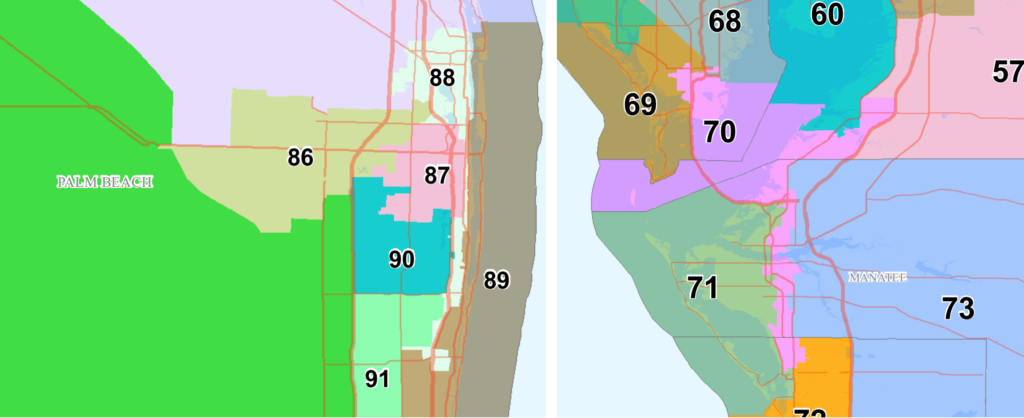

In the state house map, the legislature reviewed multiple districts and upheld multiple oddly drawn seats because they were designed to prevent retrogression of minority voters. Notable examples were the 88th and 70th – both which are historic black seats. In upholding these districts, the court did emphasize the importance of compactness but made clear that racial voting power did supersede it. Baring evidence more compact minority districts were possible, or that partisan politics dominated the decisions, the court ruled on these districts were acceptable.

What helped the case for both districts was that even with the odd shapes, the districts were not heavily African-American. The 70th was just 44% Black VAP while the 88th was just over 50% black (which was actually down from a 2002-version of the district). The 70th was a historically black district going back to the 1992 maps. The 88th had taken many forms since the 1990s, but the current iteration aimed to create a district not only for the historic African-American population of the district, but also the growing Haitian community in the area. The “tail” along its south end had a sizeable Haitian and Caribbean population.

Both of these districts highlight the complicated nature of compactness vs minority voting interests. The court discusses this at great length in its opinion.

Political intent can be hard to gage as well. The 88th especially is tricky, because its tail helps take heavily Democratic voters out of the swingish 89th. It could certainly be argued the GOP is happy with the 88th’s “tail” because it helps them preserve the 89th as a more GOP-friendly coastal district. However, baring a “smoking gun” proving that was the intent, the court could only rule on if the 88th’s tail had a legitimate function; which they found it did.

In both districts, the court reiterated an important point. Minority-district protection is a TIER ONE REQUIREMENT. Compactness is a Tier Two Requirement. Compactness must yield to mandate against retrogression.

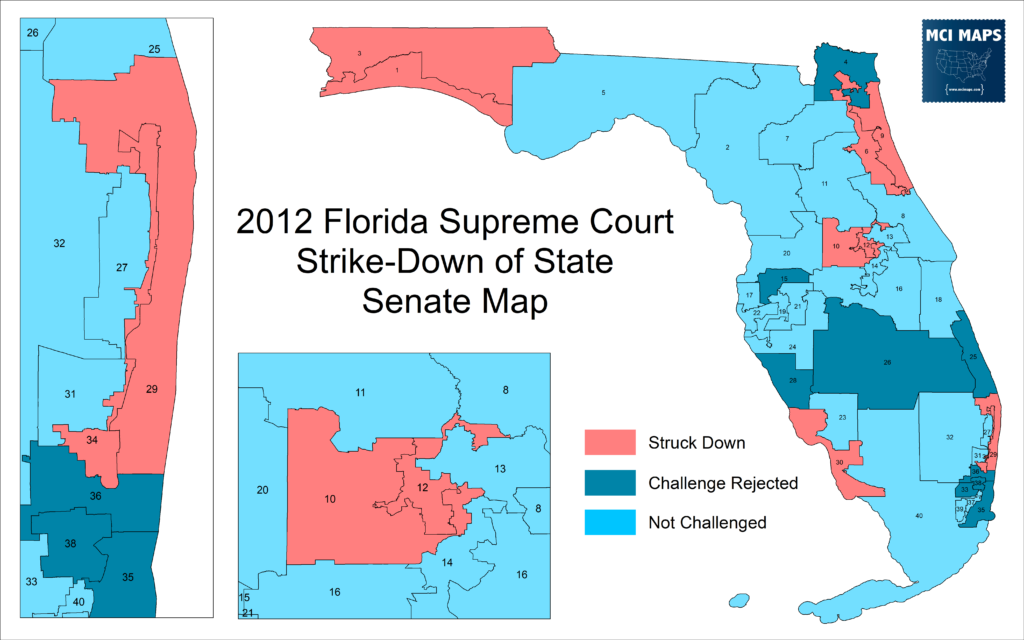

State Senate Strike-Down

The state senate plan was rejected for on multiple accounts. The court struck down multiple poorly-shaped districts; drawn either to “protect communities of interest” or “ensure the voting power of minorities.” The court took the senate to task for not using voting data or registration (the Functional Analysis) and instead relying just on only census data for determining minority districts. This was the opposite of what the house had done.

Lets take a look at these districts

Districts 6 and 9

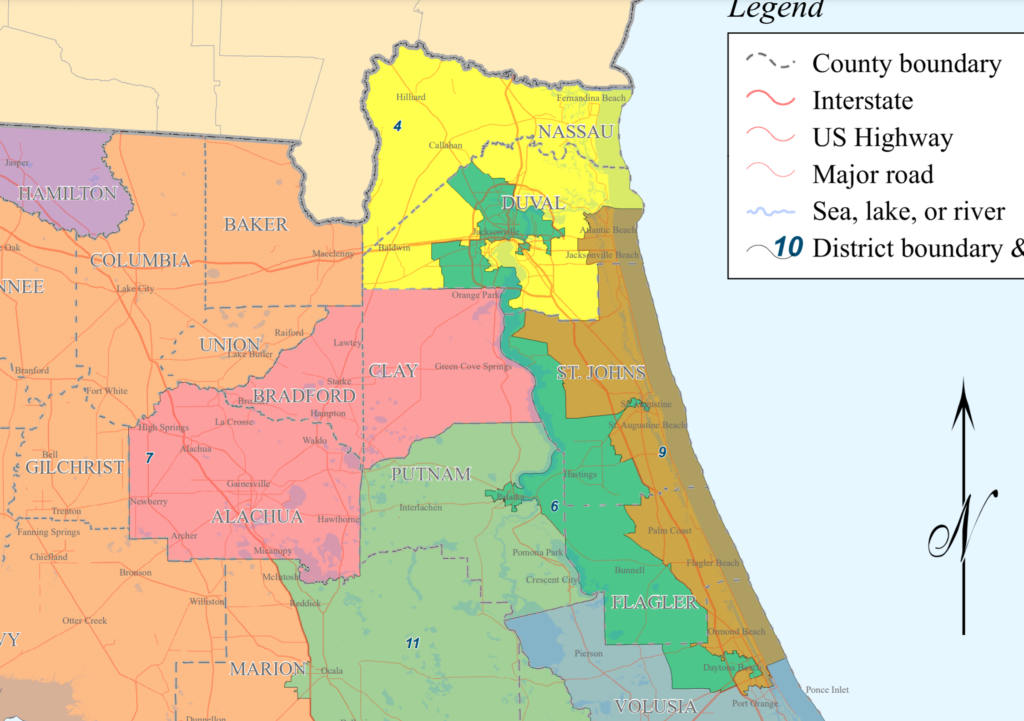

One of the big strike-downs was the plurality-black seat that stretched from Jacksonville to Daytona. The court struck this district, and its coast-hugging neighbor, the 9th, down.

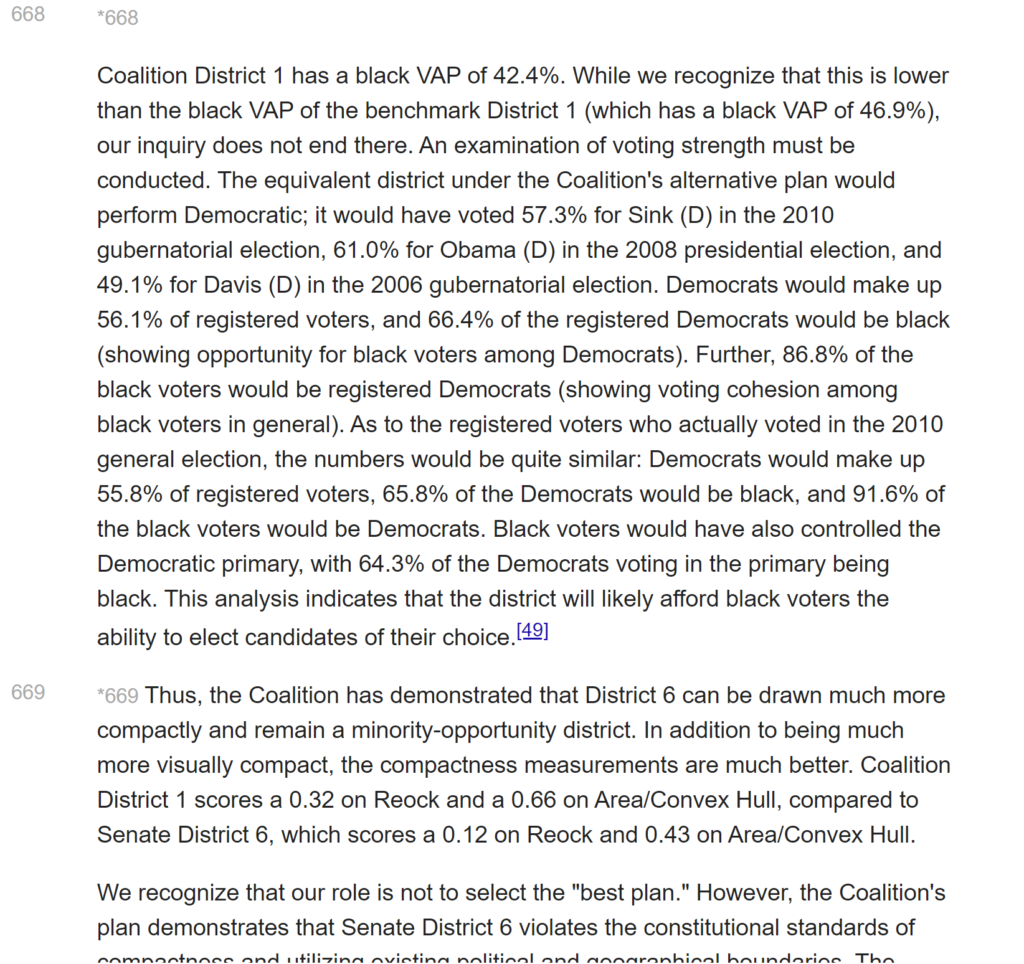

The court found that a district could be drawn in just Duval county while still being functionally black, and as such, the jagged lines and splits of counties and cities was not warranted. The court specifically cited a proposal from the coalition of plaintiffs challenged the maps – citing a proposed “district 1” located just in Duval.

Functional Analysis has been cited by the courts and is laid out by the Justice Department as a valid tool in determining the performance of a district. As we saw here, the House GOP leadership used it for their maps, so it is not merely a court-driven or “liberal” tactic.

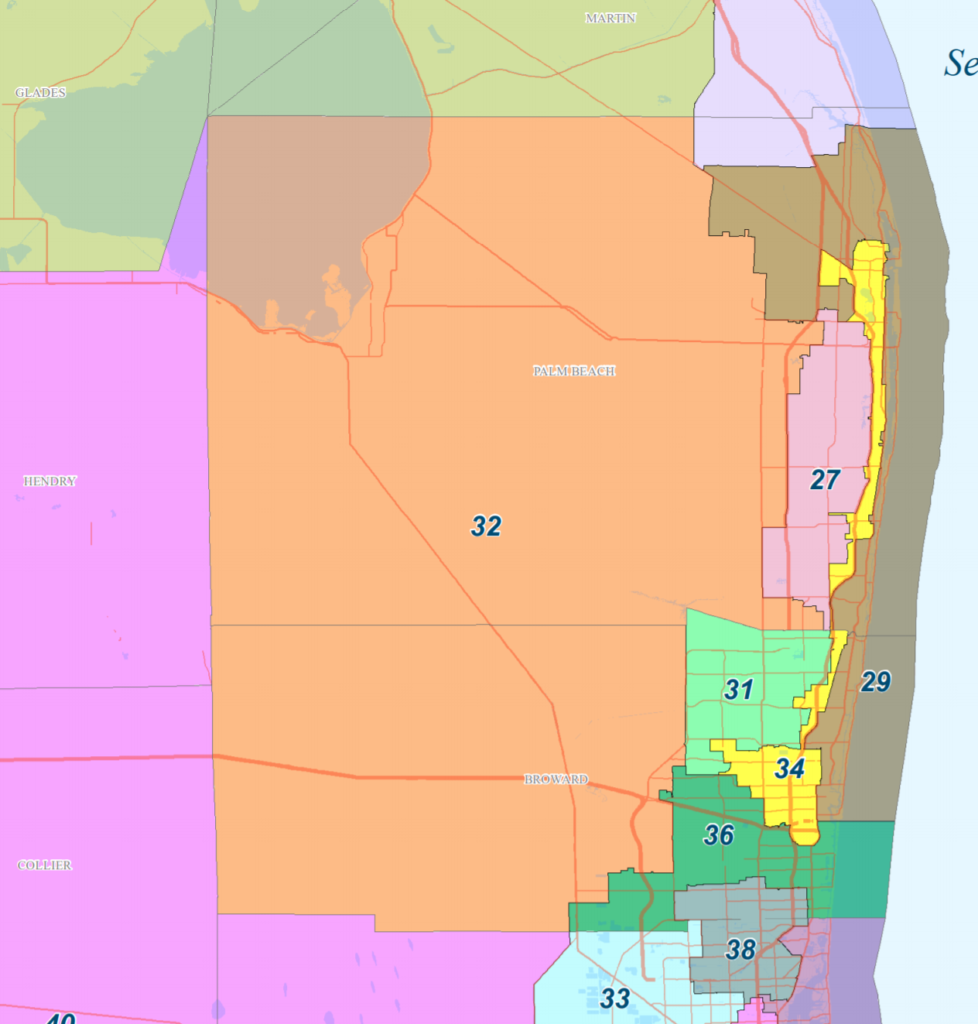

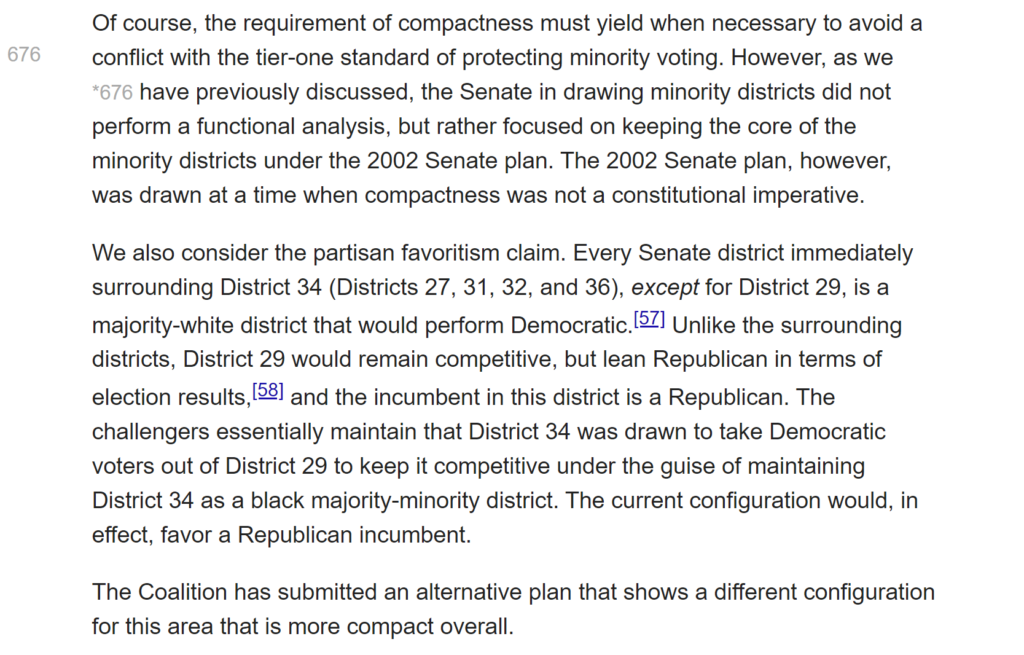

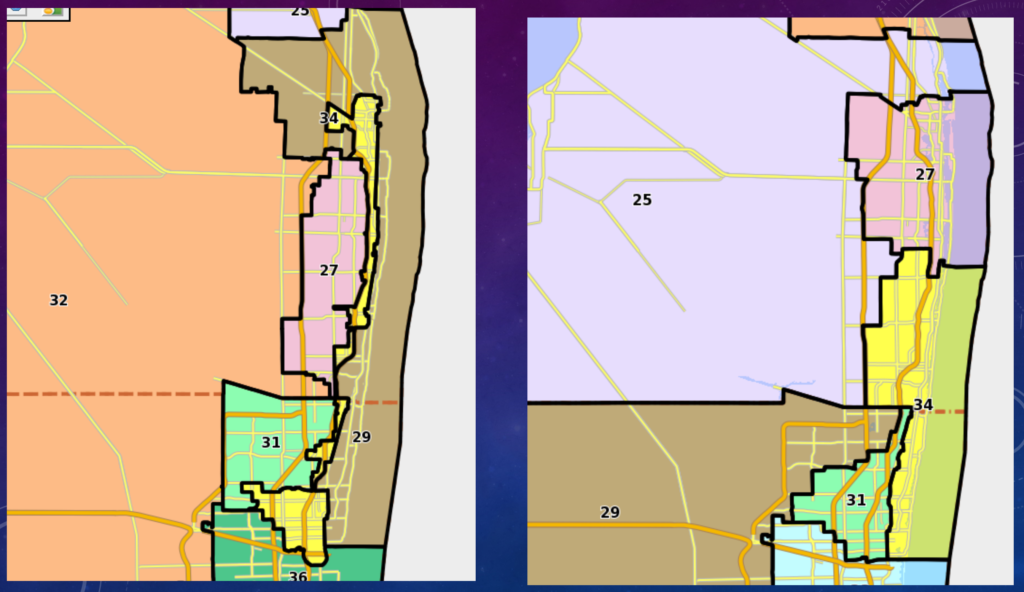

Districts 34 and 29

In addition, the court struck found that the 34th and 29th dynamic was in violation of Fair Districts. The legislature argued its plan (left) made the 34th (yellow) a strong black seat. The ruling, however, made it clear that since such a sliver was not needed to make the 34th a functionally-black seat, then it was not justifiable.

The court also found that the 29th was configured to aid the GOP. The court rejected claims that the 34th was justified by working to retain a similar shape/coverage as the old 2002 plan.

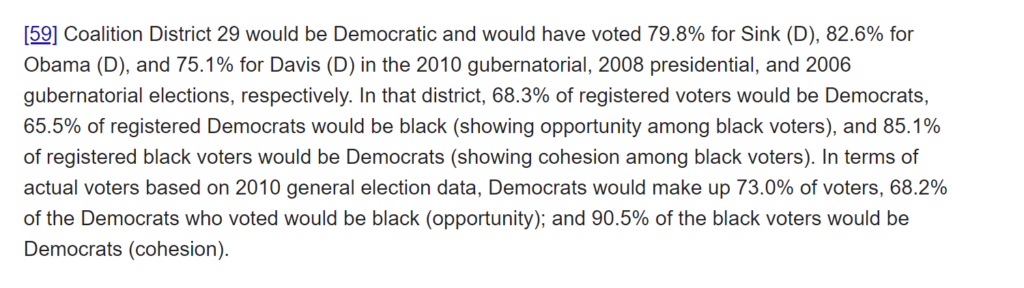

A great example of the court examining Functional Analysis for the purposes of examining minority districts is see below. Here the court was examining a proposed district from the Coalition Plaintiffs who were challenging the districts. (Note, their alternative map numbers the black-performing district as 29).

Districts 1 and 3

The panhandle districts set a precedent for what could be considered a “community of interest” under Tier 1. The Senate had continued a tradition of drawing a coast-hugging seat under a rural-heavy seat. The region is heavily Republican, so no partisan reason is at play. Rather, some in the coastal communities consider themselves a unique constituency vs the more rural inland portions of the counties. The court, however, found this justification for splitting multiple counties did not hold up; especially since the belief in rural vs coast was not nearly unanimous. The senate was forced to redraw the lines.

Districts 10 and 12

The court struck down the 10th and 12 districts in the Orlando region. The focus was largely on the 10th, which the court found used an appendage on its east end to grab a GOP incumbents address and keep them in a largely white, GOP district. The 12th, the legislature argued, was designed to be a minority opportunity district (namely it was 38% black VAP). However, the court again took the legislature to task for not performing a functional analysis. The districts were ordered for a redraw (a new version would maintain a black opportunity district).

District 30

Similar to the strike-down in the panhandle, this coast-hugging seat in a largely GOP area was struck down. The court found coastal communities are not “communities of interest.”

Rejected Challenges

A quick overview of the rejected challenges

- 4th – District rejected the claim the district split Duval too much

- 15th – Claim was lines were configured to protect a GOP incumbent – but court said evidence was needed

- 25th and 26th – Court rejected argument fewer counties could be split (since no alternative map offered)

- 28th and 33rd – Court rejected argument that since districts retained a great deal of their old 2002 lines, the districts were designed to protect GOP incumbents.

- 38th – Challenge claimed this majority-black district was packing Democratic voters. Court rejected this, pointing out district was compact. The coalition offered an alternative plan, but court found the coalition proposal was less compact.

- 35th and 36th – Court rejected claims these districts were drawn to protect incumbents, pointing out both were largely shaped by the minority districts surrounding them.

Numbering System Rejection

In addition to the Senate districts struck down, the court also struck down the numbering system for the map. The numbering was important. Florida’s redistricting process is that after a redistrict, every Senator runs in the next election. However, even-numbered districts are only electing for a two-year term. So anyone in an even-numbered district would have to get elected in 2012, then run again in 2014 (and then in 2018). Anyone in an odd-numbered district would run in 2012, but not again to 2016, then 2020. The court found that the numbering system gave a preference to incumbents, which violated the intent of Fair Districts.

The strike-down of this system would lead to a new game of a chance for determining district numbers.

New Senate Map

With the court order, the Senate went to work re-drawing the map. A special March session of the legislature was called for make changes. The Senate finalized and passed a plan, which the house pledged to back.

The plan modified 24/40 districts.

From a minority districts perspective, the biggest changes were modest reductions of the Black VAP populations in the 31st (Broward-only African-American seat) and 9th (Duval only African-American seat). These reductions were opposed by the FL NAACP, who worried the reduction could lead to a loss of minority representation. These concerns turned out to be unfounded, as the districts constantly performed as African-American districts.

All of the above districts elected either Hispanic or African-American representatives with the exception of 3 and 35. The 3rd, a longtime access/influence district, was Represented by Al Lawson until his terming out in 2010. He was replaced by Bill Montford, Leon County’s former Superintendent of Schools. The 35th, meanwhile, was represented by Gwen Margolis (of my 1990s article fame). This coast-hugging district in Miami-Dade was plurality Hispanic, but as discussed, the largely non-citizen population and weaker turnout made the district more of a white-performing district.

Partisan-wise, the biggest effect was in Southeast Florida. The changes the Senate was forced to make effectively doomed one of their GOP incumbents.

This change also ensured the electoral defeat of Republican Ellyn Bogdanoff, who needed a coast-hugging seat to win. She would have run in the 29th but was instead forced to run in the new 34th, where she lost re-election to Maria Sachs.

After the changes were made, the Florida Supreme Court signed off on the final proposal. Ruling here

Political Performance

So, how did these maps perform partisan-wise? The Florida Republicans had fiercely resisted reform. Did the proposals restrain their gerrymandering?

Well, a little yes, and a little no.

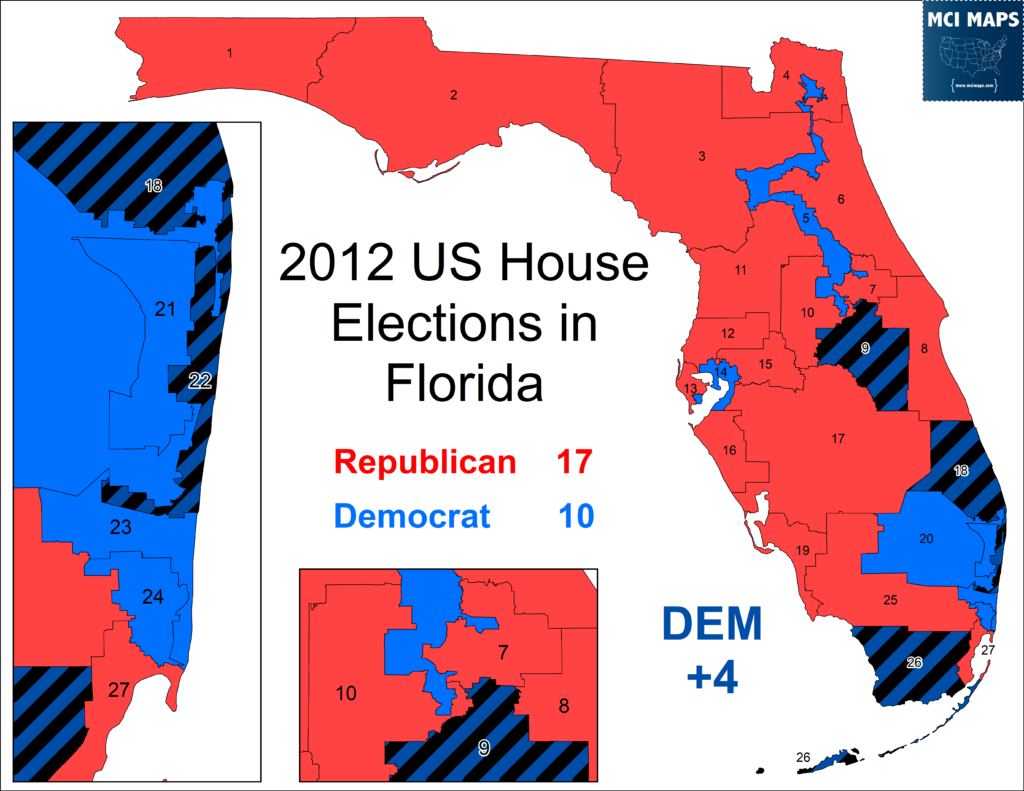

The Republicans were in a very strong position after 2010. Florida’s delegation was down to 6 Democrats and 19 Republicans; following four Democratic losses that year. Republicans were primed to lose seats, but without fair districts they’d likely have been able to stave off some losses. Democrats, aided by Obama winning Florida in his re-election bid, were able to bounce back and gain four seats.

Since Florida was gaining two seats, the GOP only really lost a net of 2 out of the state. This put the delegation at 17 to 10, which was still incredibly low for a state Obama won. In fact, Obama only one 11/27 districts in the state, a reflection of the partisan bent in the map.

Democratic wins were partly driven by redistricting, and partly driven by candidate issues.

- FL-26: This Hispanic-majority district was won by Democrat Joe Garcia, who defeating freshman Republican David Rivera; who was tainted in scandal.

- FL-09: The new plurality-Hispanic district, was considered a solidly Democratic and was easily won by Democrat Alan Grayson. This district’s creation was heavily driven by the Fair Districts Amendments and the growth in south Florida.

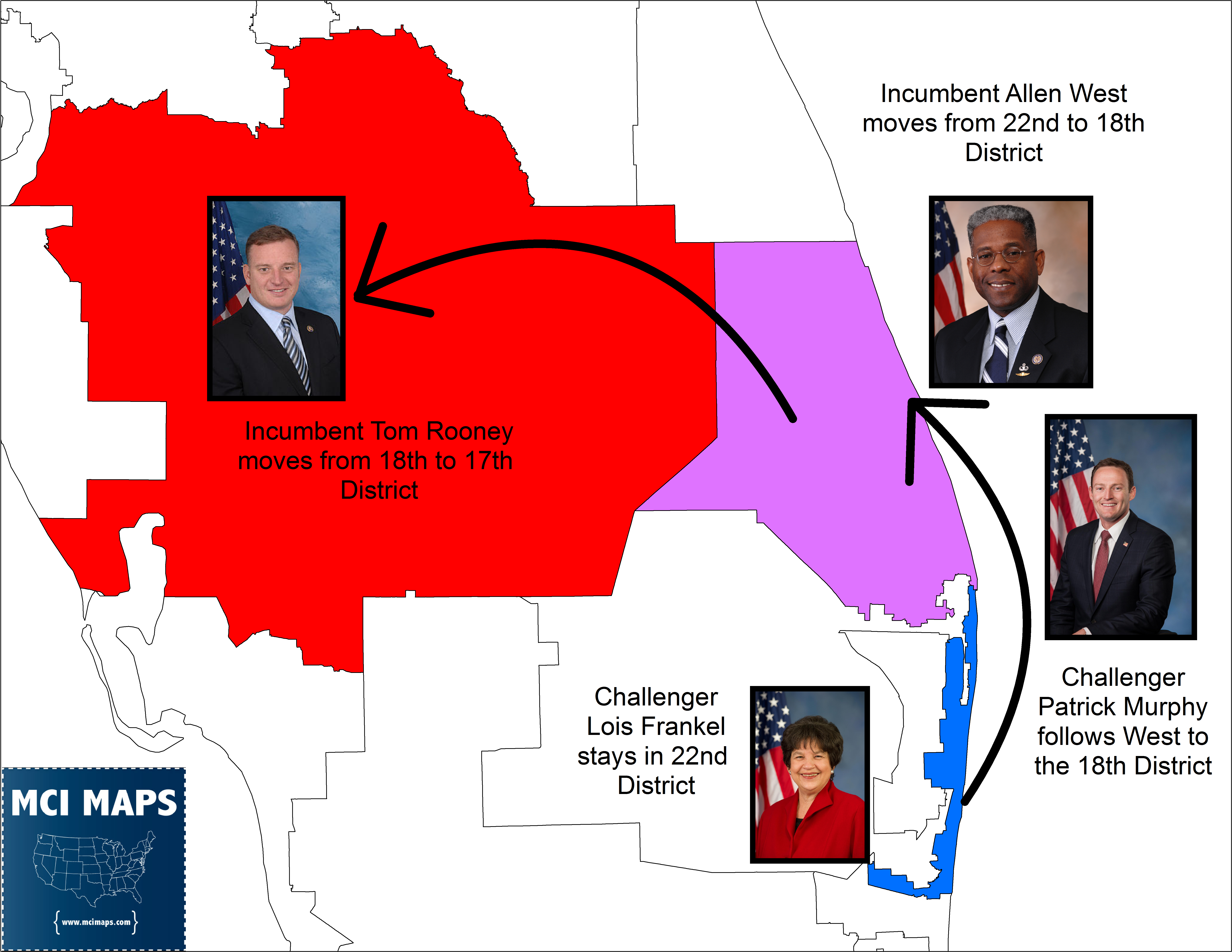

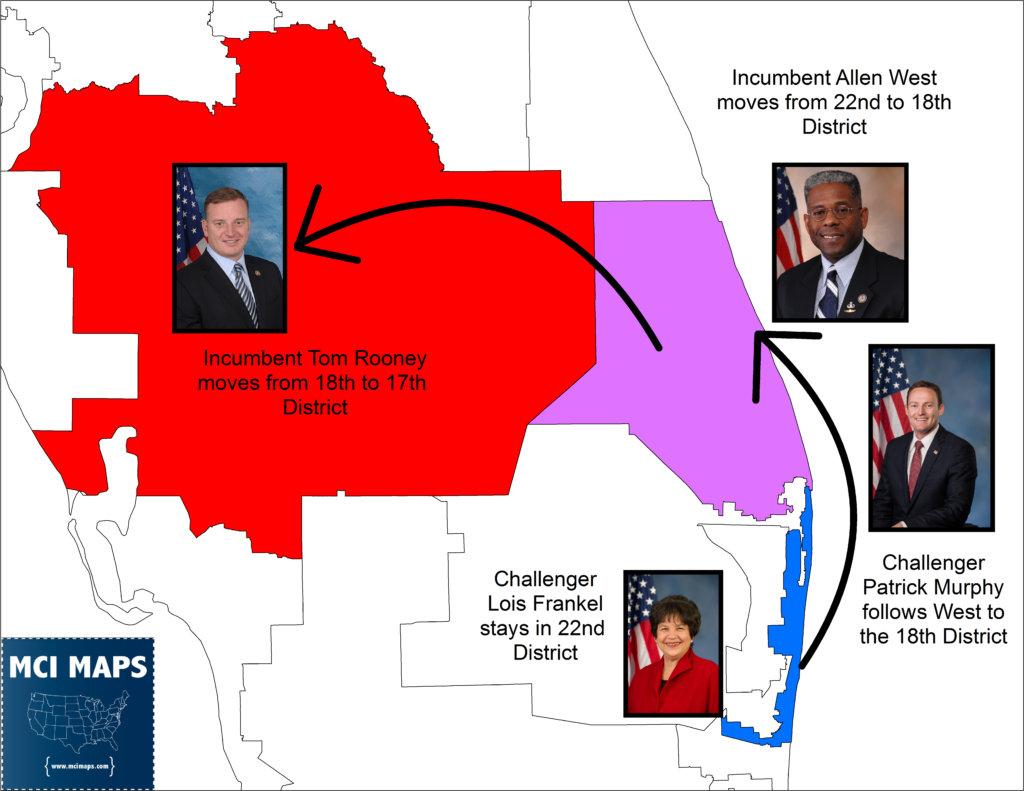

Southeast Florida is where Fair Districts likely caused the greatest shifts. In 2010, Republican Allen West had won the swingish and coast-hugging FL-22, taking it from two-term Democrat Ron Klein in the red wave. West was a controversial and very conservative Republican. In 2002, Republicans had worked to shore up the 22nd for then-Representative Clay Shaw. The Fair Districts amendments meant such efforts this time would be virtually impossible. Indeed, as new draft maps came out, it was clear a cleaned up 22nd would be solidly Democratic. MEANWHILE, two Democrats, Louis Frankel and Patrick Murphy, were already in a Democratic primary to see who would take on West in the 22nd. West, therefor, opted to move and run in the newly-formed 18th district (located around St Lucie) – which was a pure swing seat that Obama narrowly won in 2008.. The would-be-incumbent of the 18th, Tom Rooney, was happy to then jump to the super-safe 17th. Murphy, in a stunning move, opted to follow West to the 18th, leaving Frankel with the 22nd. Murphy and Frankel would win their races, flipping both seats to the Democrats.

This was a musical chairs that wouldn’t have happened without Fair Districts.

These events can be touted as Fair Districts victories. However, they gloss over the fact the map was still decidedly more GOP than the state.

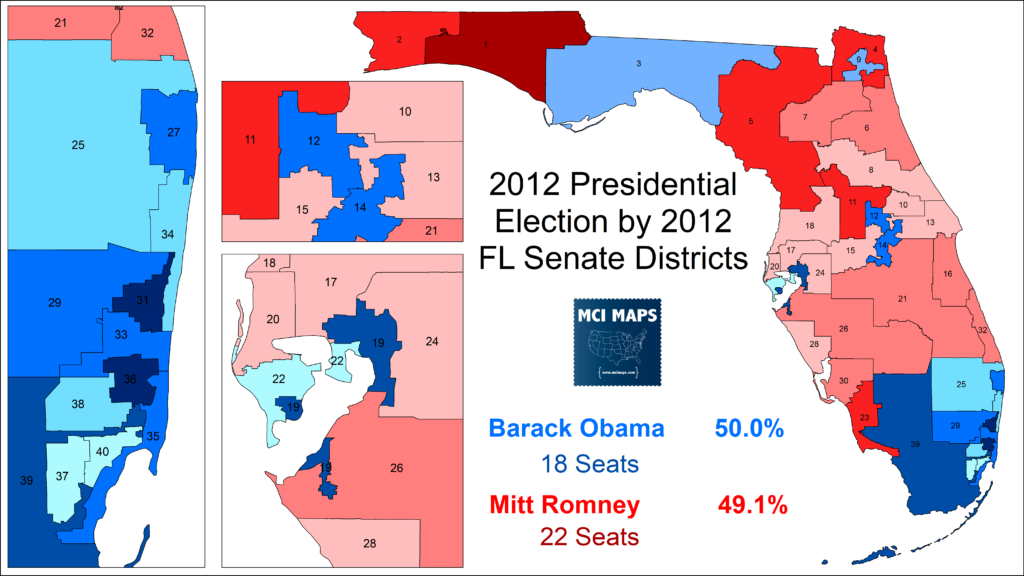

On the state Senate front, the map continued to give a distinct Republican advantage. The Republicans had long held a 26-14 advantage in the chamber, which widened to 28-12 in the 2010 wave. With the new cycle and the new map, Democrats managed to win back two seats; taking the 34th and the 14th.

- 14: Now-Congressman Darren Soto won this new Hispanic-plurality seat in the Orlando region. Unlike Miami-Dade, the central Florida Hispanic community is solidly Democratic

- 34: As discussed earlier, the Supreme Court ordered redraw doomed Incumbent Ellyn Bogdanoff, who’d won in the 2010 red rave.

When looking at how the Presidential race broke down by State Senate district, Obama still lost a majority of districts despite winning the state.

The seat breakdown may seem close, but it actually conceals a solid GOP edge. Three of Obama’s districts were won by under 0.5% of the vote. SD40 had a margin of under 200 raw votes, and depending on how you break down federal absentees and split precincts, you could argue either Romney or Obama won it (I almost made it a tie on the map). Meanwhile, all 22 Romney seats had a 3% margin or greater. The median Presidential margin by Senate District was 4.6% Republican.

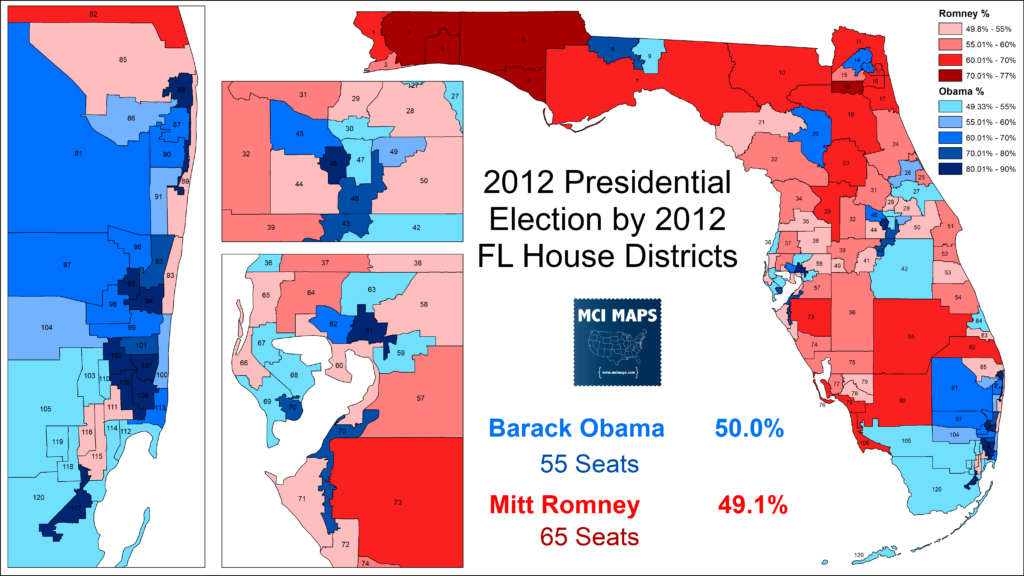

The State House map, similar to the Senate, retained a modest but steady Republican edge. Democrats would make a handful of gains in 2012 thanks to recovering from losses in 2010, but the map remained solidly Republican.

Obama would lose a majority of districts in both 2012 and in 2008. The median Presidential result in the districts was a Republican margin of 3.5%.

The coalition that pushed for the Fair Districts Amendments did not view the maps as fair. Lawsuits and discovery were promised, with reformers firmly believing that the lawmakers worked to circumvent the rules against political gerrymandering.

Looming Lawsuit and Strike-Down

For those who follow Florida politics, you surely know about what would come next. A lawsuit pushed by the Fair Districts coalition would reveal the FL GOP worked behind the scenes to gerrymander the maps and put on the mirage of an open and fair process. This would lead to a redraws of the State Senate and Congressional maps in 2015. Next week, I will look at those lawsuits, the the findings, and the crazy 2015 special sessions.