This article is #5 in my series on the history of redistricting in Florida. Last week, I looked at Florida’s redistricting battle in the 1990s. This would mark the last time Democrats controlled the process in Florida. From here on, we move away from Democrats trying to gerrymander the lines and onto Republican efforts to lock in their own control.

Political Background

Democratic Decline

By the time the 2002 redistricting process began, Florida’s Republican Party was already beginning to cement its control. The Senate flipped in 1994, followed by the house in 1996. Jeb Bush’s 1998 Gubernatorial win gave the GOP full control of Florida’s government for the first time since Reconstruction. Republican margins in the legislature would grow; with chamber control never in doubt in 1998 or 2000. Many Democrats decried the 1992 maps for dooming them; claiming the creation of majority-minority districts bleached everything surrounding. However, this glosses over the fact Democratic candidates were losing to ticket-splitting as well. Democrats lost Congressional seats that otherwise voted for Lawson Chiles in 1994. In 1996, the Republicans won the Florida State House the same day that Bill Clinton beat Bob Dole in a majority of the districts.

Florida’s Democratic Party was on the losing end of an electoral realignment in the sunshine state. This was driven by midwestern migration, Cuban refugees, and a shift in rural voters toward Republicans. The 1990s maps are not what knocked them out of power.

Republican Plans for Redistricting

When redistricting talk began in 2001, Republicans promised to make redistricting the most open process in state history. Like the times when Democrats made this same promise, the truth was entirely the opposite. Republicans found themselves in charge of the line drawing for the first time in Florida history. Like any party in power, they would work to cement their majority. Florida was also going to get TWO additional Congressional districts; and the pressure to ensure those were GOP seats was immense.

The Republicans were in a much stronger position in 2002 than Democrats were in 1992. Adhering to the Voting Rights Act was much easier for the GOP; who had no electoral issue with creating majority-black districts. Meanwhile, the creation of Hispanic seats in Miami-Dade largely meant the creation of Republican districts. The Republican leaders also had the benefit of a decade of DOJ lawsuits and court cases. The notion of what was mandated by the VRA was clearer in 2002 than 1992; even while being foggy at times. Regardless, the Republicans had a clear benchmark to structure the minority districts around; a big benefit.

Redistricting Process

This link includes a great summary of news articles on the 2002 redistricting process

Republican leaders appeared to believe they’d always be able to come to an agreement on lines. Lawmakers began working on maps in the winter of 2001, with the first plans coming out of committees at the beginning of January 2002. The legislative session was scheduled to begin on January 22nd, and the goal was to avoid a special session. Both chambers agreed to let the House and Senate pass their own chamber’s maps. The only compromise would have to be in the Congressional plan.

Partisan Process

In 1992, Democrats did not include Republicans in the map-drawing process. In 2002, the Republicans returned the favor. The GOP was concerned with adhering to the VRA and drawing a plan that would maximize their gains. In the state legislature, the GOP already had commanding majorities: 77-43 in the House and 25-15 in the Senate. Their maps would aim to codify those margins. The Republicans did not hide their intentions. Their was no rule against political gerrymandering, and the GOP made it clear that their maps aimed to protect GOP incumbents and take some Democrat-held seats.

The GOP and Minority Districts

The Republican’s in 2001 were fortunate to already have several benchmark districts to work off of. The State already had three African-American and two Hispanic Congressional districts. Demographic change meant a third Hispanic district was likely warranted in the Miami-Dade region. Republicans made their intention for a third Cuban-Hispanic district in the southeast Florida region; with State Senator Mario Diaz-Balart (brother of Congressman Lincoln) having eyes the new seat. Balart also served as the redistricting chair for the State Senate; ensuring he was in a strong position to direct the new lines.

Democrats, meanwhile, did not support such a third Hispanic district in Miami-Dade; and instead called for a Hispanic-Black coalition seat in the Orlando area. However, their idea never gained any traction with the Republican leadership.

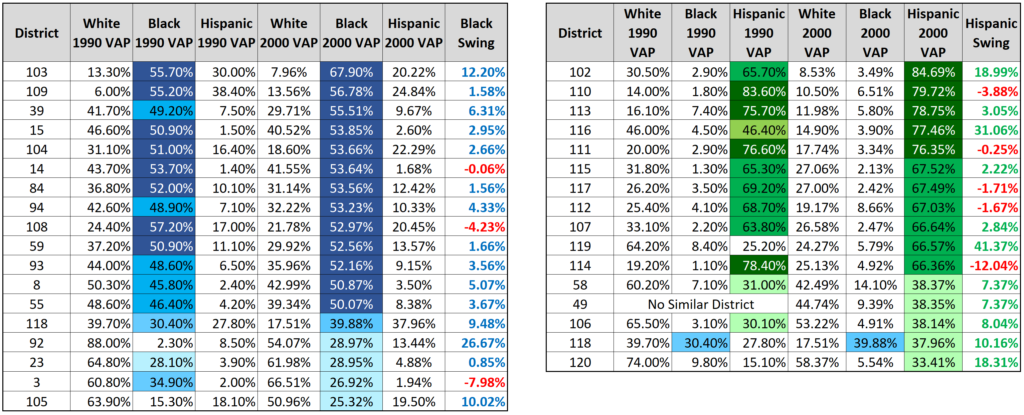

Republicans also made efforts to increase the minority share of state house and state senate districts. Many seats that were 40-45% African-American in 1992 (and were electing black members) were super-charged to majority-black

Speaker Feeney’s Congressional Seat

Perhaps the biggest issue that could trip up the House and Senate was the the ambitions of State House Speaker Tom Feeney. The Speaker made it very clear that he wanted to run for Congress; having already raised over $100,000 for a campaign. Feeney worked to steer a Congressional seat that would include his current district; nestled in eastern Orange and Seminole counties. Feeney did not have a good relationship with Senate President John McKay; who had no plans for a Congressional run and wasn’t moved by Feeney’s ambition. The two men had been on the opposite sides of multiple policy fights; with Feeney a much more brazen firebrand Conservative and McKay more reserved. Perhaps no better example of this was the 2000 recount for Florida. McKay, while support Bush, encouraged patience and going through the courts. Feeney favored just having the state declare its electors for Bush and ignoring a recount. (Sound familiar?).

It should be no surprise that when the house released its proposed Congressional plan, it included a new seat for Feeney. It is also no surprise that the State Senate’s plan for Congress did not include such a district. However, despite the differences, it was made clear that the chances of a compromise were there. McKay wanted the house to back a tax reform package that Feeney would not put up for a vote. It was made pretty clear in the press that support for the package would likely be leveraged by the state senate. This turned out to be exactly how things played out. The house passed its proposal. The State Senate held off on any final votes. Feeney agreed to the tax reform. The Senate drafted a map with a seat for Feeney, all sides came together and approved a proposal. Done and done.

The legislative maps were passed on March 22nd, and Jeb Bush signed the Congressional map on March 27th. On May 3rd, the Florida Supreme Court signed off on the maps.

DOJ Challenge to State House

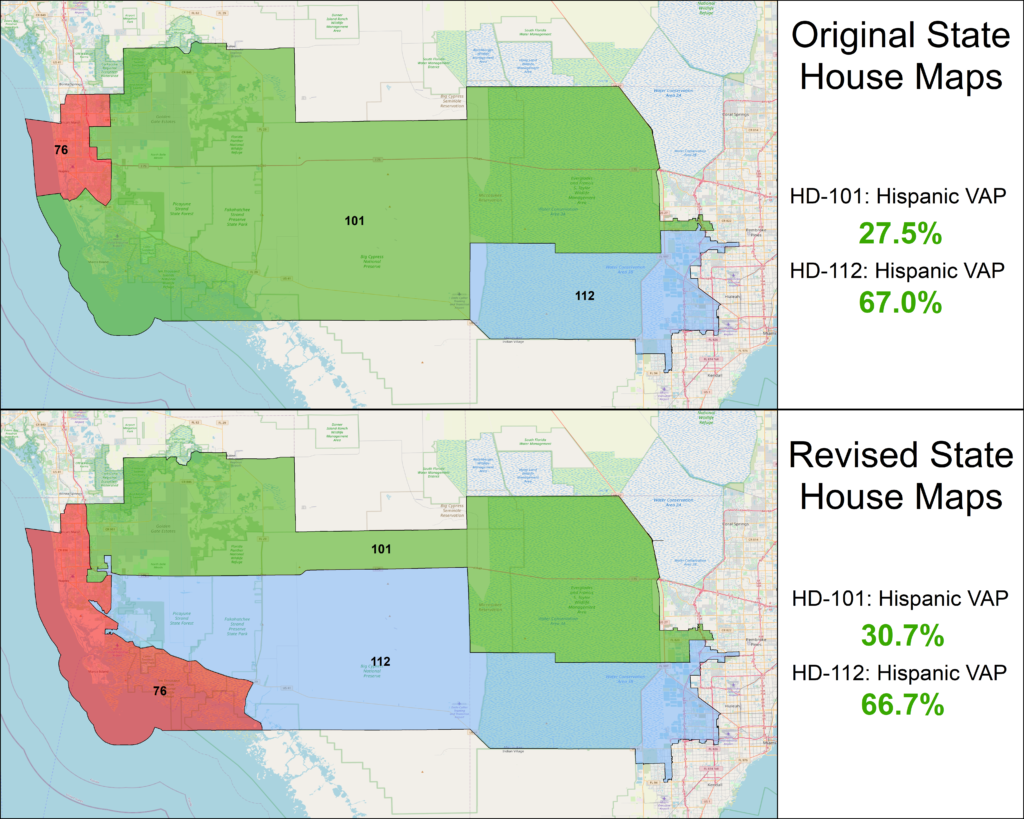

After the maps were passed, they were submitted to the DOJ for preclearance. Only five counties: Hillsborough, Collier, Hendry, Monroe, and Hardee; were subject to preclearance. On July 1st, the DOJ found the Congressional and Senate lines passed muster; but raised objections to the Collier region in the state house. The DOJ argued that the Hispanic minority in Collier county needed to be given the opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice. In the 1992 map, these voters were part of a Collier-Dade, majority-Hispanic district. The 2002 House plan put those Hispanics into a Broward-Collier seat that was just 28% Hispanic. The overall number of Hispanic-majority seats went up statewide, but the DOJ rejected the Collier Hispanic change.

The House tried to argue that since the number of Hispanic districts increased, the state did not engage in retrogression. The DOJ disagreed. On July 2nd, Speaker Feeney submitted to the court an alternative map that only changed three districts. This plan was approved by the court for use.

The changes put a large portion of Collier’s Hispanic population into the majority-Hispanic HD112. The Collier portion of this the district was 46% Hispanic, 42% white.

The Supreme Court of Florida signed off on the changes. The map would be formalized in 2003 with a legislative vote.

The Maps

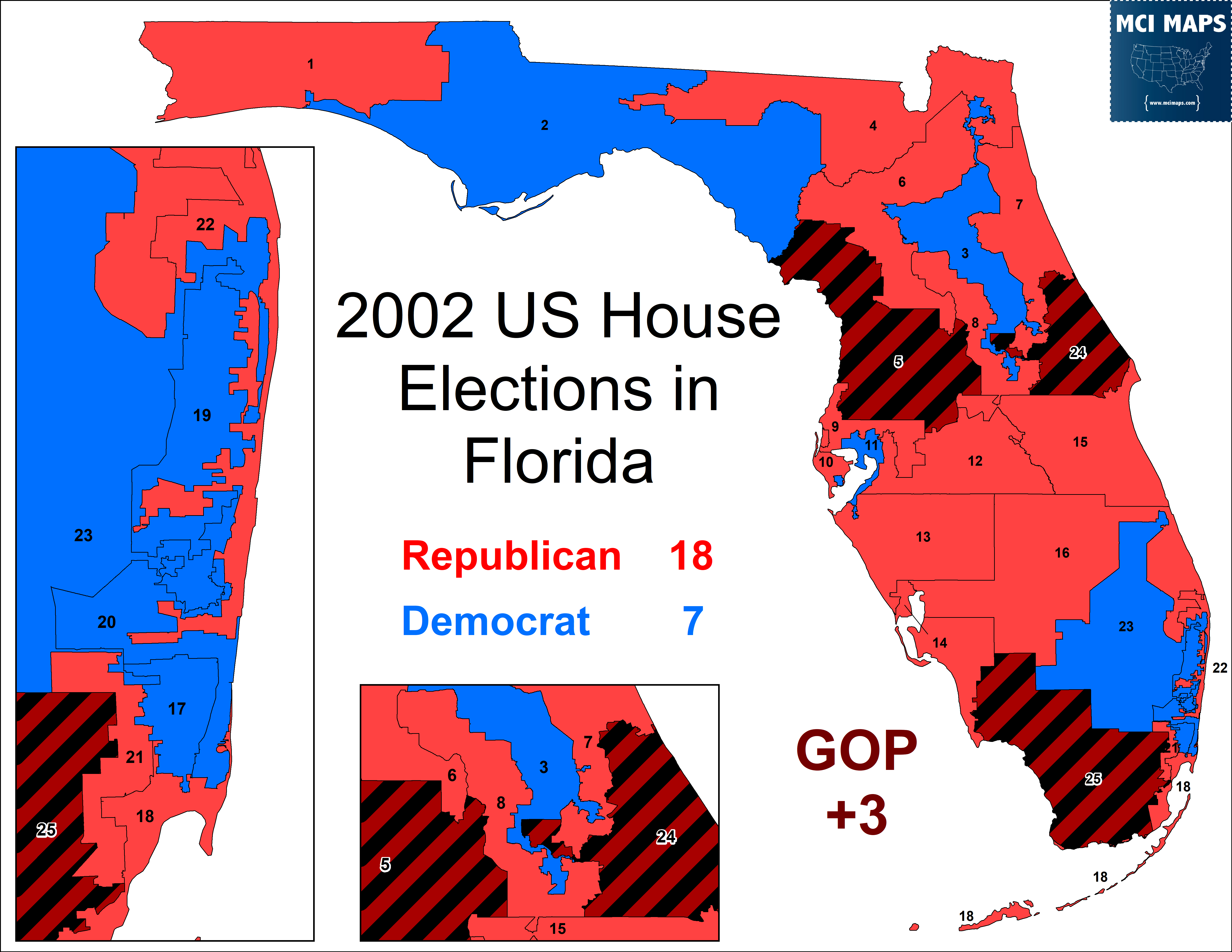

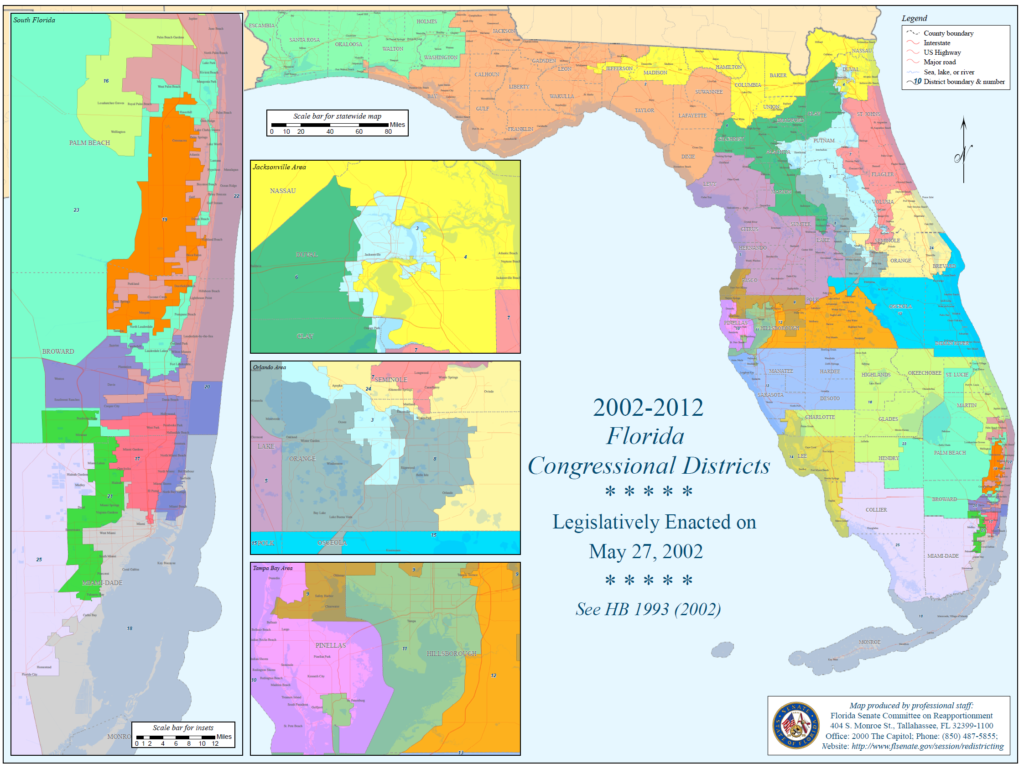

Despite the early divide between the house and senate, the final Congressional map was passed without a special election or court order. It heavily favored Republicans.

The proposal included the following minority districts

- FL-03: 46.2% Black VAP (50.6% Black)

- FL-17: 53.9% Black VAP (57.9% Black)

- FL-23: 49.3% Black VAP (54.6% Black)

- FL-18: 62.0% Hispanic VAP (60.8% Hispanic)

- FL-21: 70.8% Hispanic VAP (68.2% Hispanic)

- FL-25: 63.2% Hispanic VAP (61.2% Hispanic)

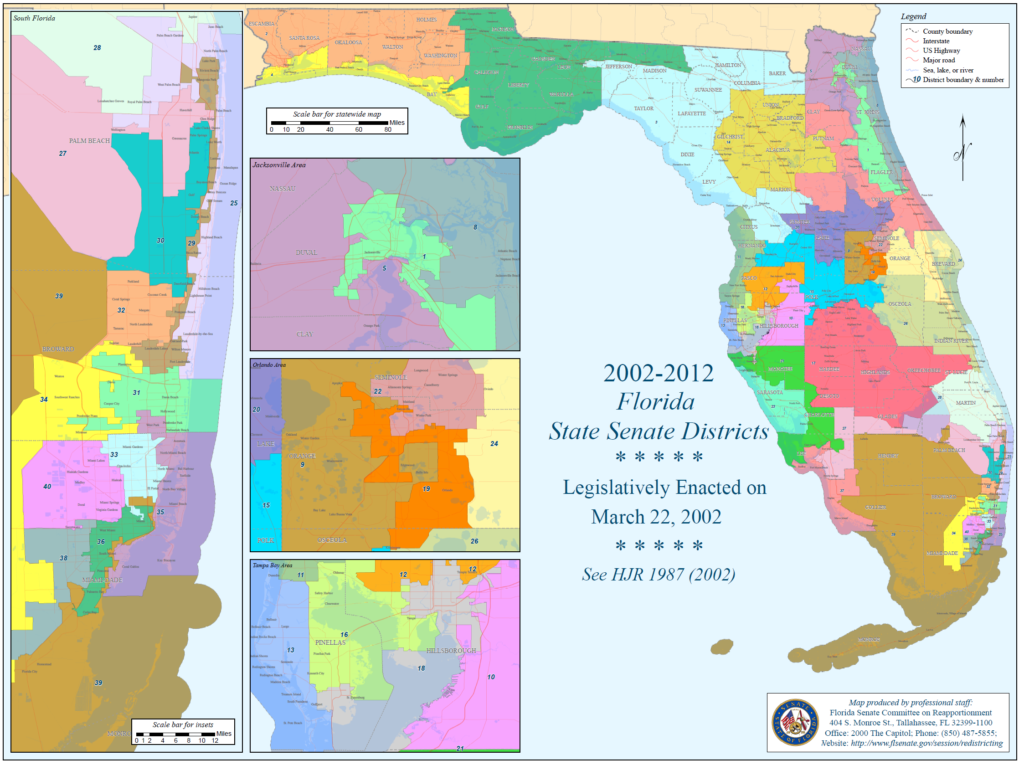

The state senate map maintained minority districts already in place and worked to solidify the GOP’s 25-15 majority.

The State House map, with three districts adjusted per the DOJ objection, saw an increase in Hispanic districts and was a very extreme Republican gerrymander.

These maps would remain in place for the entire decade.

Breakdown of the Lines

Partisan Congressional Efforts

Multiple areas of the map involved efforts by the Republicans to lock in a lopsided Congressional delegation. The efforts of the GOP were as follows…

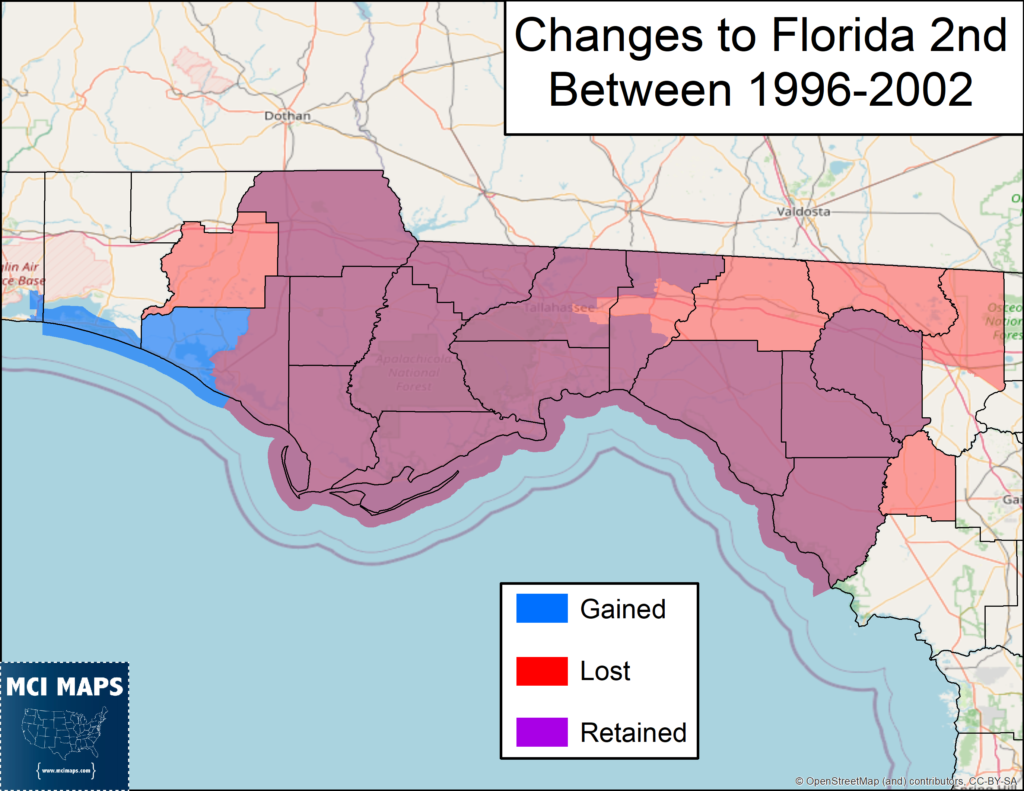

- FL-02: Remove Democratic voters from Leon and Jefferson. Goal was to recruit State Comptroller Bob Milligan to run against Democratic incumbent Allen Boyd.

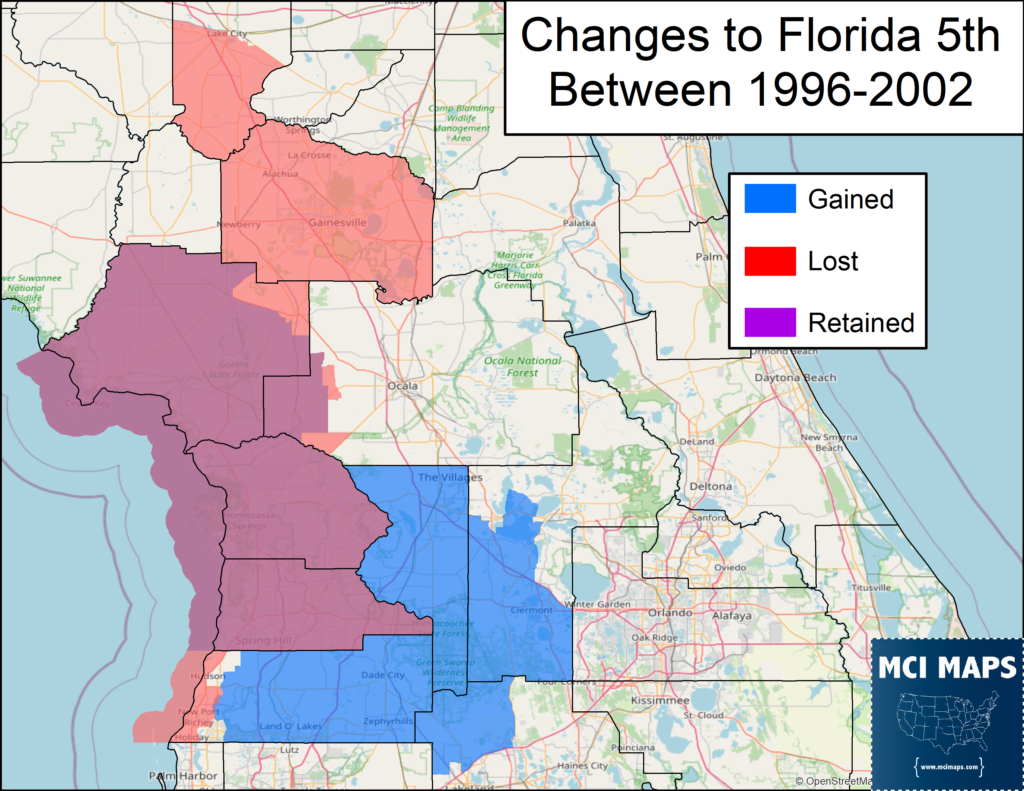

- FL-05: Remove Democratic voters in Alachua, add in more Republicans. Goal was to knock off Democratic Congresswoman Karen Thurmond.

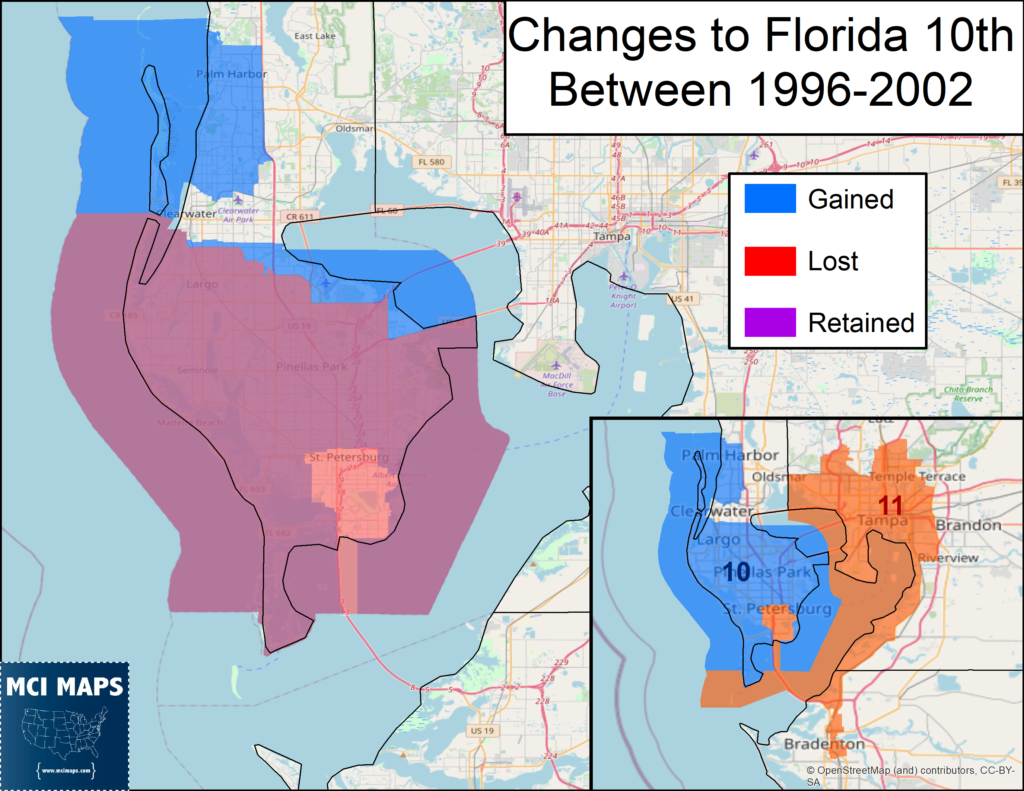

- FL-10: African-American voters in St Petersburg were removed from Republican Bill Young’s district; and added to Democratic Jim Davis’ Tampa-based Congressional seat.

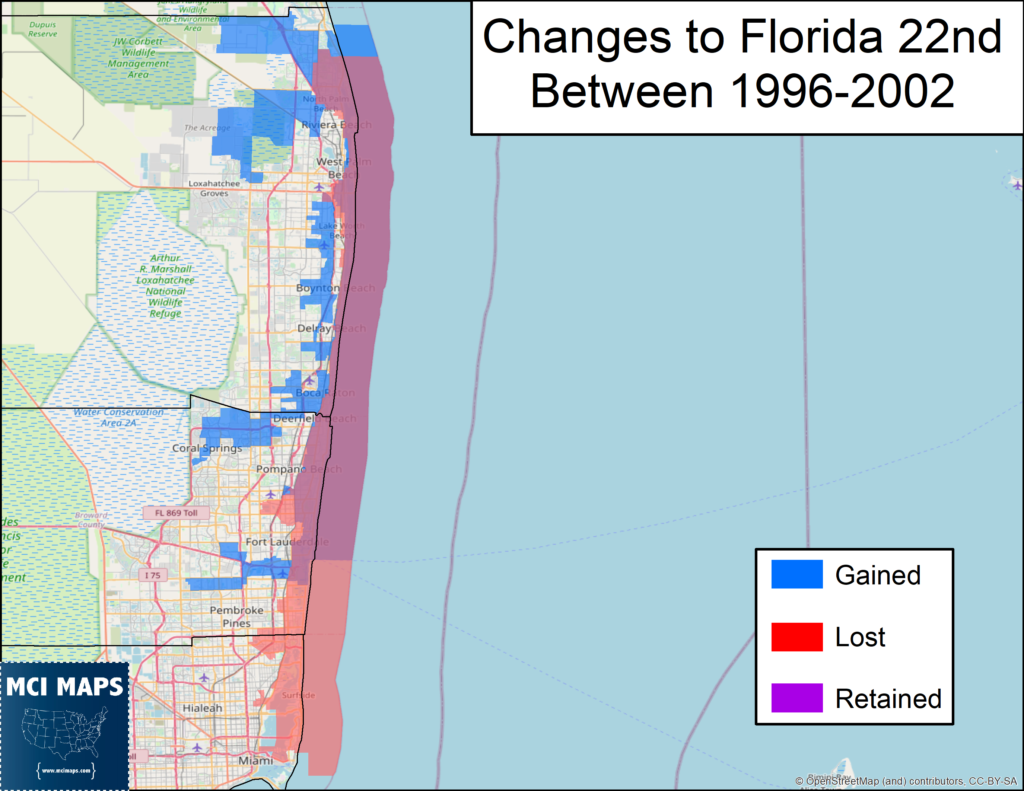

- FL-22: Republican Clay Shaw (who only won re-election by under 1,000 votes) saw his district move out of Miami-Beach and further North – up to the treasure coast in Palm Beach. This made the district several points more Republican

- FL-24: This seat was drawn for Republican Speaker Tom Feeney

- FL-25: The third Hispanic-majority district, while likely mandated by the VRA, was drawn to be an easy win for Senator Mario Diaz-Balart.

These efforts to lock in a solidly Republican delegation came true. Republicans won both of the new districts; and ousted Karen Thurmond in the 5th.

Shaw had no trouble winning until he was swept out in the 2006 midterms. Boyd, meanwhile, had largely secure re-elections until his 2010 loss (with Milligan never making the run). The delegation always remained solidly Republican. Democrats flipped the 8th and 24th in the 2008 blue wave, but lost them right back in 2010 (along with the 2nd and 22nd).

Minority District Changes

For much of the 2001 redistricting process, the legislature had a good working relationship with many minority groups. In contrast to the contentious situation of the 1990s, the NAACP was largely on board with the legislative proposals. The Hispanic caucus was likewise happy with how the maps turned out. This isn’t too surprising when we look at the final products.

Hispanics, reflecting their growth in the state, ended up with additional districts. HD116 and HD119 both became majority Hispanic. Hispanic growth in the Orlando region also resulted in HD58 holding a sizable Hispanic minority.

Many of the plurality African-American districts (which were electing black members) became majority-minority. HD118 also became a functional African-American seat as well. In Broward, HD92 became an access seat, as did 105 in Miami-Dade.

The increases in African-American % in some districts was related to population changes. However, in many other instances, the tactic by the GOP was to pack as many African-Americans as possible – bleaching the surrounding seats. This became part of the overall Republican tactic; packing minority voters and claiming it is needed to adhere to the VRA. In essence, packing when it was not needed.

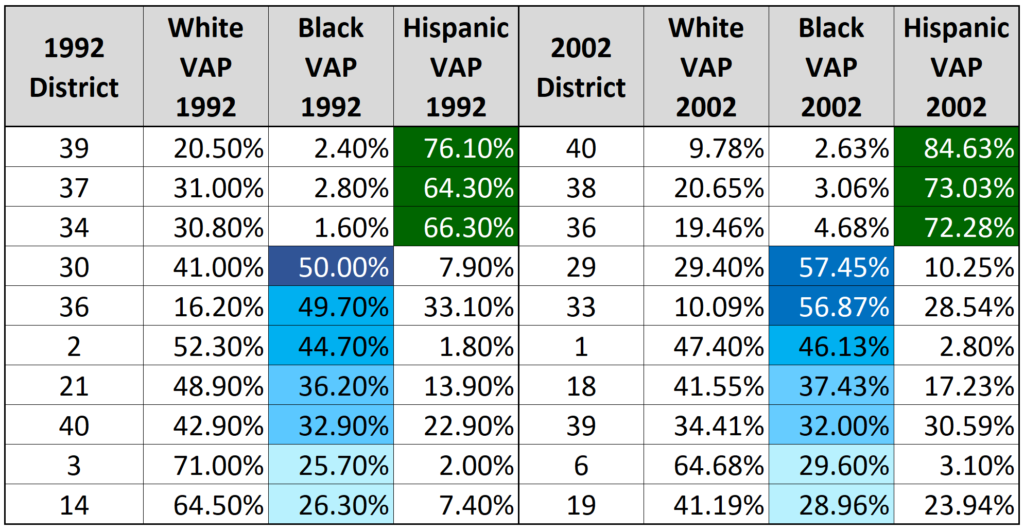

The Senate map largely preserved the minority makeup of the 1990s districts. (Note some numbering changed). The three Hispanic-majority districts saw a further reduction in the anglo-vote, a reflection of Miami-Dade’s continued demographic transformation. While creating four majority-Hispanic districts was likely possible, the large non-citizen share of Dade Hispanics (many who were refugees), meant true Hispanic seats often needed to super-majority Hispanic.

In a fashion similar to the state house plan, some African-American districts saw their BVAP % increased. The 30th and 36th further consolidated black voters

Partisan Effect on the Legislative Map

Republicans never tried to hide their intentions with any maps. They wanted maps that would adhere to the VRA while also rigging the lines in their favor. This is something they admit in court in the Martinez v Bush lawsuit filed by many Democratic-aligned plaintiffs. In the end, there was nothing for the courts to strike down. The maps adhered to the VRA, and political gerrymandering was not against the Florida Constitution.

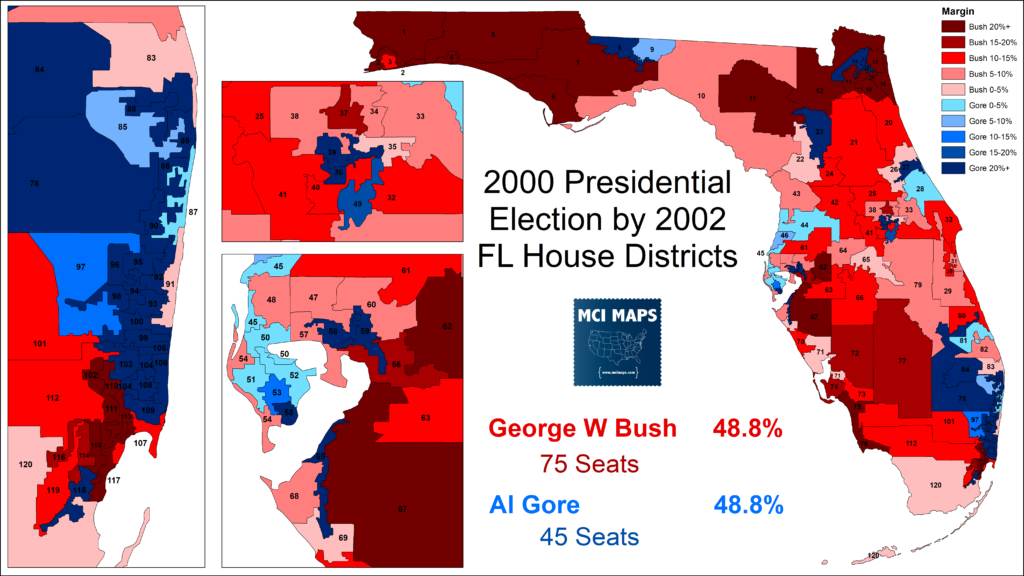

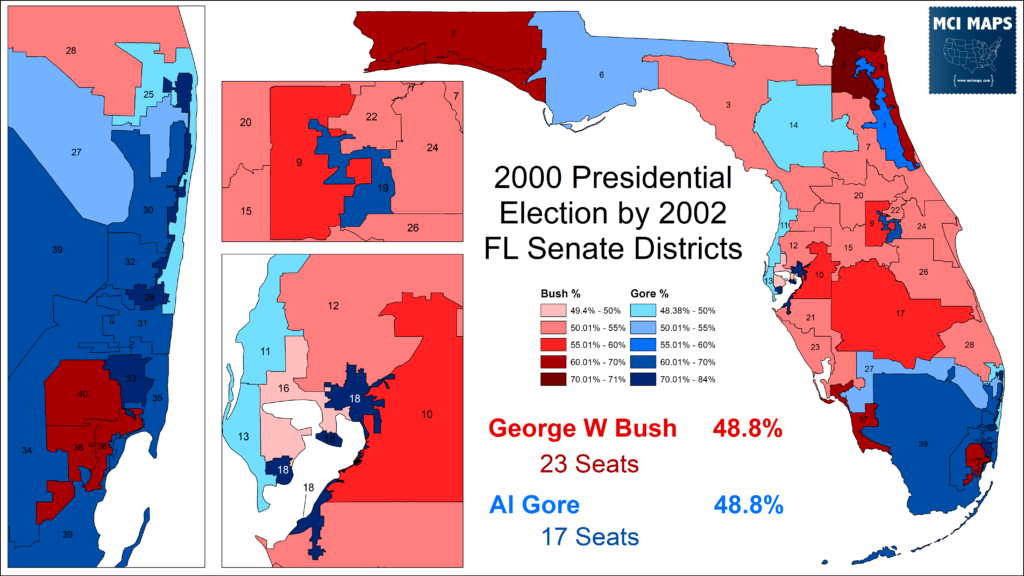

The gerrymandering was very effective. The State House map was especially masterful. Looking at how the 2000 Presidential Election (the famous 500 vote margin) by house district reveals just how extreme the gerrymander was.

Bush won 30 more seats than Gore despite the extremely narrow result.

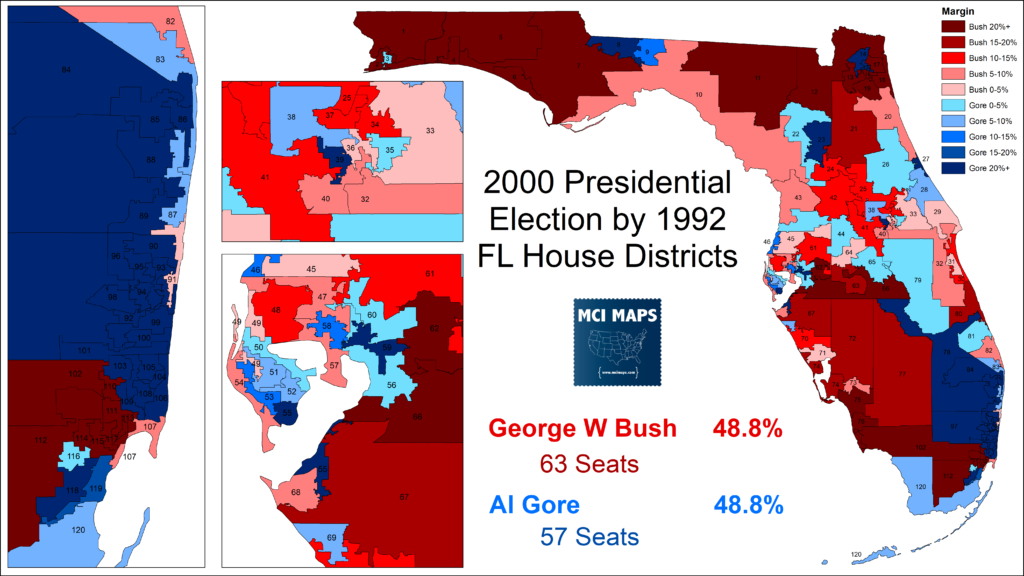

As a counter example, here is that same election broken down by the 1992 lines.

This was a Democratic-drawn map; but one they effectively passed in protest under the threat of Voting Rights Act. It provides a seat breakdown much more indicative of a close election.

The State Senate map tells a similar story. Looking at the Presidential race, 23/40 districts voted for Bush. However, two of the Gore seats were won by razor thin margins of under 100 votes. Bush won steady majorities in over half the seats.

The House and Senate maps performed strong for the GOP through the decade. Granted this was a time of GOP dominance in the state. However, the maps made any Democratic flip in a wave year virtually impossible. For Republicans, this was sweet revenge for the 1980s and 1990s redistricting battles.

Conclusion

The Republican gerrymandering of 2002 made Democrats realize they had no chance to regain control in Florida if something didn’t change. In the 1990s, many Democrats had balked at efforts for independent redistricting commissions; something that seemed increasingly appealing after the 1992 redistricting saga. Out of power, the Democrats and their allies would team up with good-government groups to push a series of redistricting reforms. Next week we will look at that campaign and the passage of the Fair District’s Amendments.