This week’s article is #3 in my series on redistricting in Florida. Last week’s article looked at redistricting in the 1970s and 1980s; a time when minority voters pushed for district representation yet often were short-changed. The 1990s would be a very different process, however. After the passage of the 1982 Amendment to the Voting Rights Act, minority voters had much great power to demand districts drawn for their communities. This new mandate would clash with Florida Democratic leadership; who were trying to preserve a shrinking legislative majority. The result would be a chaotic redistricting saga that led to multiple special sessions and years of court cases.

This week’s article will focus on the political dynamics in Florida and the redistricting process for the state house and state senate districts in the 1990s. Next week will look at the Congressional remapping.

Legal Background

The 1990s redistricting process was the first held after the passage of the 1982 Amendments to Voting Rights Act. The biggest change to come out of 1982 was an expansion of Section 2: which until that point made it clear that discriminatory voting systems were illegal. However, after the Supreme Court case of Mobile v Bolden (1980), where the court found that the VRA does not offer a protection unless discrimination is the intent, pressure was on congress to make changes to the law. The fact was, intent is hard to prove. As a result, Congress approved a “results test” for Section 2. This meant that if the voting system had a negative impact on a minority group; they had standing to sue under the Voting Rights Act. For redistricting purposes, the issue of “vote dilution” – either via cracking or packing – was the primary issue.

In 1986, the Supreme Court gave its precedent-setting ruling in Thornburg v Gingles (1986). The case struck down multi-member districts in the North Carolina assembly. In the majority opinion, the court laid out three conditions for future plaintiffs to use for lawsuits under Section 2 of the VRA.

- The racial/language minority is large enough and compact enough to make up a majority of a single member district

- The minority group is politically cohesive (aka they can/do vote as a block)

- The majority racial block often votes as a unit to deny minority candidates victory in elections.

The result of the amendment to the Voting Rights Act, as well as the Gingles court decision, led many legislatures across the country to conclude that maximizing minority districts was a legal priority. The George HW Bush Department of Justice made it clear to lawmakers across the states that failure to create minority districts could be a reason for failed preclearance under Section 5 of the VRA.

Political Background

When the 1990 census figures came out, they revealed that Florida’s population had grown by a staggering 30%. As a result, the state was entitled to FOUR new congressional districts. As Florida had continued to grow, so had Republican strength in the state. Voter registration in 1982 was a 63%-31% advantage for Democrats. By 1992 it was down to 52%-41%. Republicans continued to gain ground in the legislature, with Democrats controlling the Senate by just 22-18 and the House by 74-46.

The pressure to draw more minority districts placed the white democratic leadership under tremendous pressure to protect its incumbents while also satisfying legal requirements. A big part of Florida’s growth was a rapid rise in non-white voters; especially in the southeast. This put many white Democratic incumbents in a precarious position, as only a handful of “anglo” seats in Miami-Dade would be left; far fewer than the number of white incumbents in the region.

African-American & Republican Alliance?

The narrative about the 1990s redistricting process paints a story of African-Americans uniting with Republicans to push for more minority districts. This is an oversimplification of the story. What is indisputable is that African-Americans were demanding greater voices and a share of the districts.

Republicans had aligned with African-Americans in the 1970s to push for the end of multi-member districts. This time, they tried to forge an alliance again over redistricting. African-Americans were willing to work with whoever, but the relationship with the GOP was not always easy. Well before 1992, Republicans began pushing the narrative that white Democrats did not want to give African-Americans their own districts. Republicans State Senator Kirk Kiser said

Democrats “could enhance minority representation or hold down the number of republican seats, but it could not do both”

However, there was plenty of distrust around these efforts. Democratic State Rep Mike Langton said

Republicans are “trying to appear as if they’re the great protectors of black and minority representation, and that’s not really their intention. They are doing this it for pure partisan political reasons”

Efforts by Republican operatives put them at odds with many African-American politicians. One major blow up happened when Republican operatives funded radio ads on African-American stations where a narrator claimed to be an African-American activists who was attacking the white democratic leadership for its hesitance on minority districts. The NAACP and many black lawmakers were furious at the move.

Meanwhile, the Democratic leadership was terrified of losing its majority and working behind the scenes to make African-American politicians and activists happy while at the same time keep the most aggressive maps from becoming law. Part of this effort involved getting Governor Lawton Chiles to hint (but never say) that any aggressive “rebel map” (aka one not supported by leadership) would be vetoed.

State Legislative Redistricting

The redistricting process of 1992 was planned out well in advance. Lawmakers spent years working on getting the software ready for computer-based drawing of lines and held 32 public hearings on redistricting between September and December of 1991. All sides expected the redistricting process to be a major fight; especially with the Democratic leadership trying to adhere to the Voting Rights Act will also trying to protect their majority.

Legislative Process

As the legislature began its redistricting process for both the Congressional and legislative maps, several broad themes emerged.

- The white Democratic leadership wanted to lock in its majorities and did not want to create too many majority-black districts. Leadership preferred “access” seats where the African-American voting age population (VAP) was between 25%-50% of the district. This would allow Democrats to pad their districts with reliable Democratic voters.

- African-American lawmakers and organizations wanted more seats, but there was a divide within the community on how aggressive to be. Some favoring maximizing the number of majority-black districts, while the NAACP and other politicians favored getting concessions but not “packing” so much that it led to GOP control.

- Hispanics Republicans in Miami-Dade wanted more districts to reflect their growth through the 1980s. It was also important that Hispanic VAP was high to account for turnout dynamics and the non-citizenship of many refugees. To keep it simple, a 55% Hispanic seat was not a guaranteed Hispanic-performing district.

- Republicans portrayed themselves as allies of Hispanic and African-American lawmakers, arguing for more minority districts (and often the most extreme bizarre lines).

On top of all this was a distrust between the House and Senate leadership – something that would boil over in the Congressional and legislative debate.

State Senate Debate

The initial plan released by the State Senate leadership did not feature an expansion of minority districts. The plan aimed to sure-up the two African-American districts in the map. This proposal was roundly criticized. It sparked the unprecedented move of the state house; which offered up its own state senate plan. This plan, a break for the decorum of both chambers sticking to their side, was much more aggressive, and called for 4 majority-black districts and 2 access districts. Another Senate plan was proposed by African-American State Reps Corrine Brown and Darryl Reaves, which created 4 black-majority districts and 3 access districts.

The State Senators were angered by the house proposals, which put many incumbents at risk and made the Senate look bad for its lack of minority consideration. The Senators warned of retribution with their own map of the state house.

State House Debate

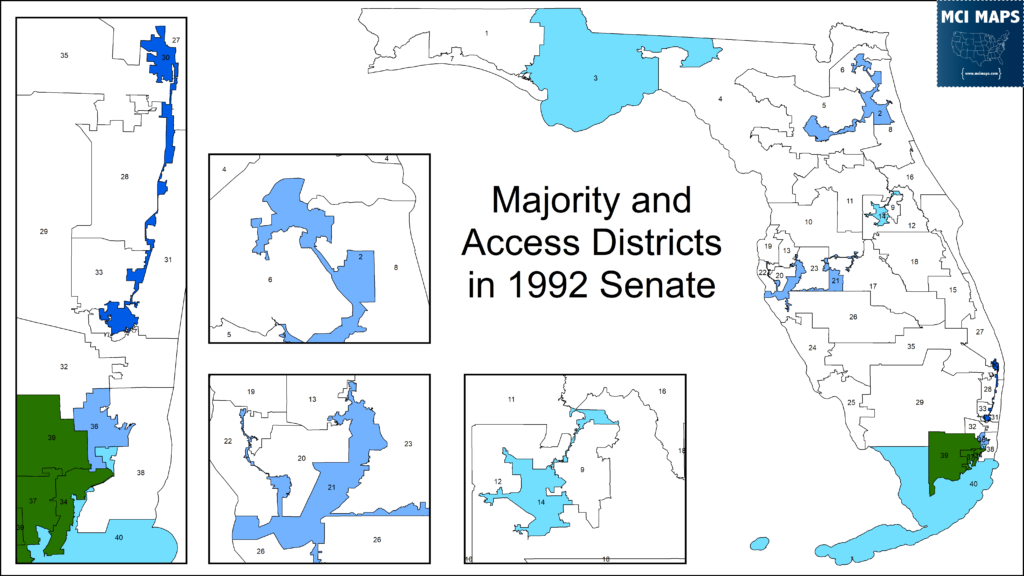

The State House plan proposed by leadership called for increasing the number of African-American districts from 11 to 15. This proposal appeased many black caucus members, however, as the session went on, some divide in the caucus grew. Hispanic Republicans, meanwhile, were angered that the plan did change the number of Hispanic-majority districts; which remained at 7. The Hispanic caucus offered their own plan, which created 18 African-American districts and 11 Hispanic districts.

Special Session on Redistricting

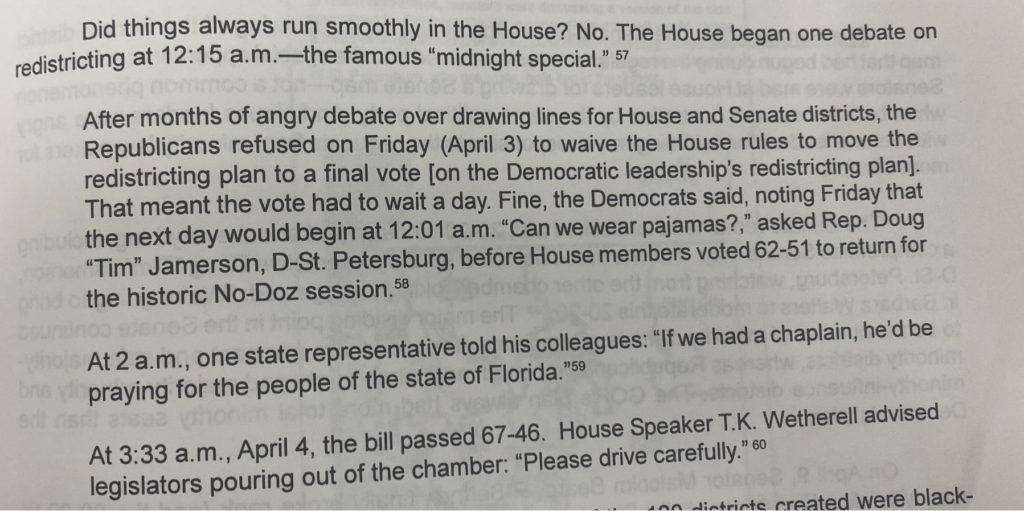

In the original legislative session, neither chamber could agree on final maps for the house and senate. The two chambers were already at loggerheads over the Congressional map, and the tension there dragged the legislative maps down as well. A special session would be needed to try and iron out an agreement. However, before lawmakers could meet for a special session on the house/senate redistricting, a special session for Congressional redistricting was needed. The special session for the Congressional map redraw was held from March 23rd to April 2nd and it did not yield an agreement. That session was gaveled out on April 1st, and Governor Chiles announced a special session for the house/senate redistricting to begin April 2nd.

The special session saw the house and senate remain at loggerheads over the number of minority districts the state senate should have. Tensions got so high that the Senate actually passed a state house plan drawn by the GOP; a form of payback. In the end, the house leadership plan would be approved. Its passage was actually quiet the story itself.

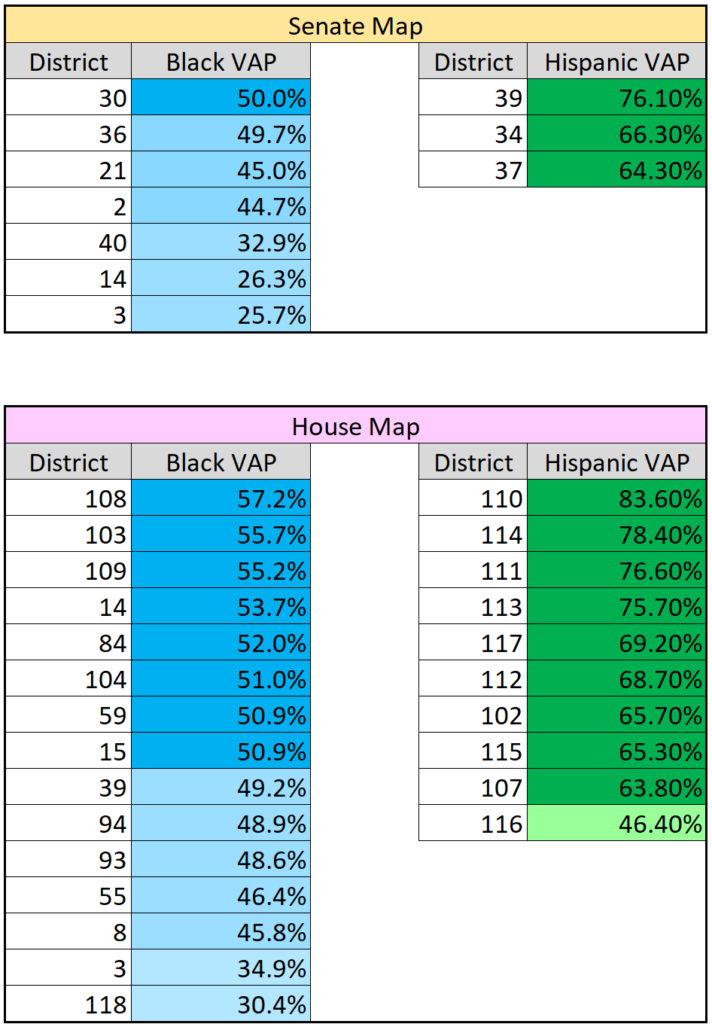

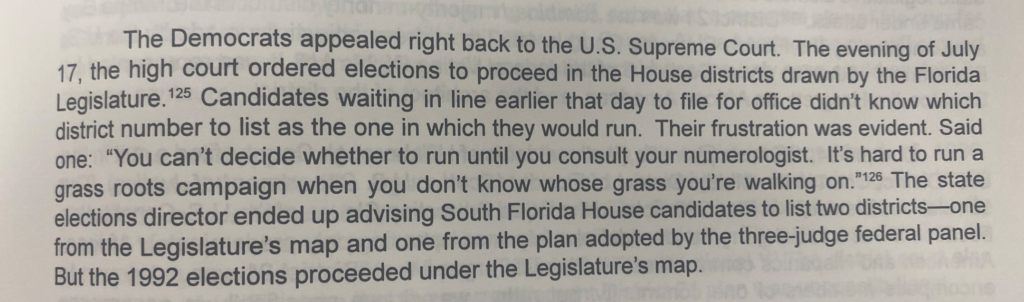

The state house plan created 13 majority-black districts and 2 access seats; in addition to 9 majority-Hispanic and 7 access seats. It was also had a Democratic registration advantage for 67/120 district.

The State Senate, meanwhile, was deadlocked 20-20. The congressional special session saw two Democrats: Larry Plummer and Vince Bruner, defected to vote with the GOP on rejecting the plans. This deadlocked continued for the legislative maps. The Senate finally agreed on a compromise map that offered more minority districts; but the chamber was still deadlocked. Finally, Republican Malcolm Beard defected and backed the map. Republicans, furious with Beard, claimed the Senator was given a favorable district. Beard said he preferred the compromise map than the uncertainty of leaving the courts in charge of drawing even more districts. The plan created two majority black seats, three access seats, and three Hispanic majority seats. Democrats topped Republicans in registration for 24/40 districts.

Supreme Court Review

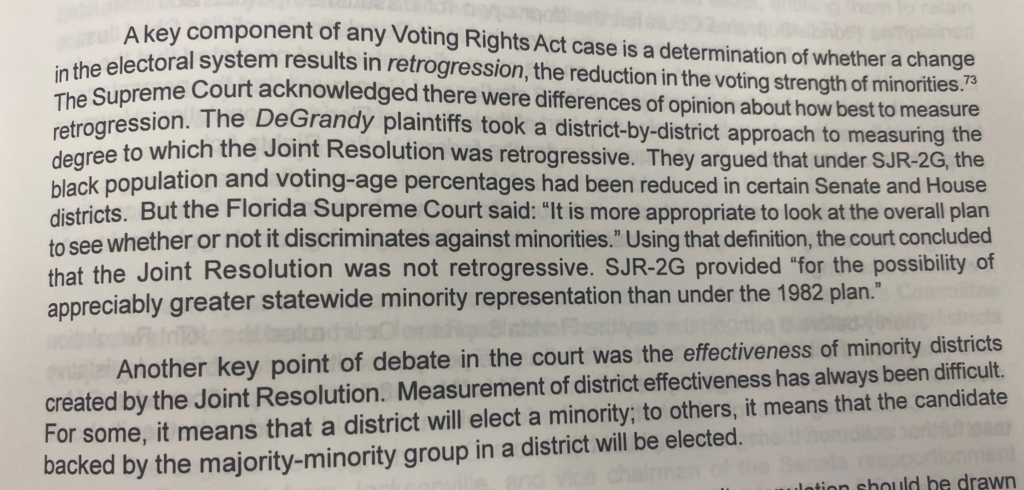

With house and senate plans finally passed, it was now onto the Supreme Court of Florida for review. The supporters of the plans were Democratic leaders. The opponents were Republicans and the NAACP. The constitution gave the court 30 days to make a ruling on the plans; but the court openly acknowledged that that was not nearly enough time to do a complicating Voting Rights Act analysis. The debate over whether the maps included retrogression (the reduction of minority voting strength) came down to whether you viewed that on a district-by-district or map-as-a-whole perspective.

The other major issue was what share of a district being a minority group was needed to be an effective minority districts. Data on this subject was still new; and while many called for maximizing minority strength wherever possible, other experts argued the 1980s elections had shown districts where minorities won office in seats with 50%+ white populations.

In the end, the Supreme Court ruled it could not do a comprehensive analysis. Rather, based on testimony and data provided, they could only offer if the maps were facially valid; while leaving the door open to future suits. The court subsequently ruled 6-1 to sign off on the maps. The lone dissenter was Chief Justice Leander Shaw, the court’s lone African-American.

DOJ Rejection

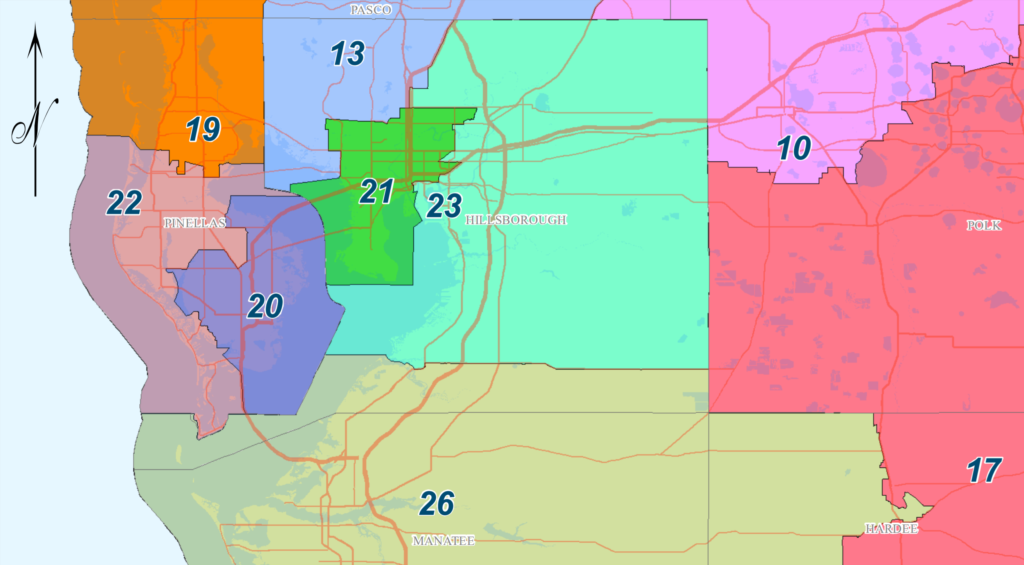

The Attorney General of Florida submitted the plans to the Department of Justice for review. The preclearance provisions for Florida only applied to five counties: Hillsborough Collier, Hardee, Monroe, and Hendry. However it was expected the DOJ, which has already struck down plans in many southern states, would expand its ruling. On June 16th, the DOJ denied preclearance for the lack of a black seat in the Tampa Bay region.

Following this, on June 23rd, the DOJ filed suit against Florida over the state house lines in Escambia and Miami-Dade. In Miami-Dade, the DOJ argued the state senate and state house lines deprived Hispanics of additional seats. In Escambia, the DOJ argued the black population could have been kept together under one black-access seat.

Fixing Tampa Bay

The Supreme Court of Florida tried to get the legislature to agree to come into special session and fix the plans. However, the legislature was already in its THIRD special session, this one over taxes and the budget. Burned out on redistricting, lawmakers balked at taking the task up again.

The only absolutely pressing issue was fixing the Tampa Bay region. The lawsuit over the Escambia and Miami-Dade regions would have to go through the courts. Tampa’s fix was needed to get preclearance. However, Republicans tried to use the situation to push for a full redraw. Democrats and the NAACP were on the same page for this, however, and favored keeping the remapping localized to the Tampa region.

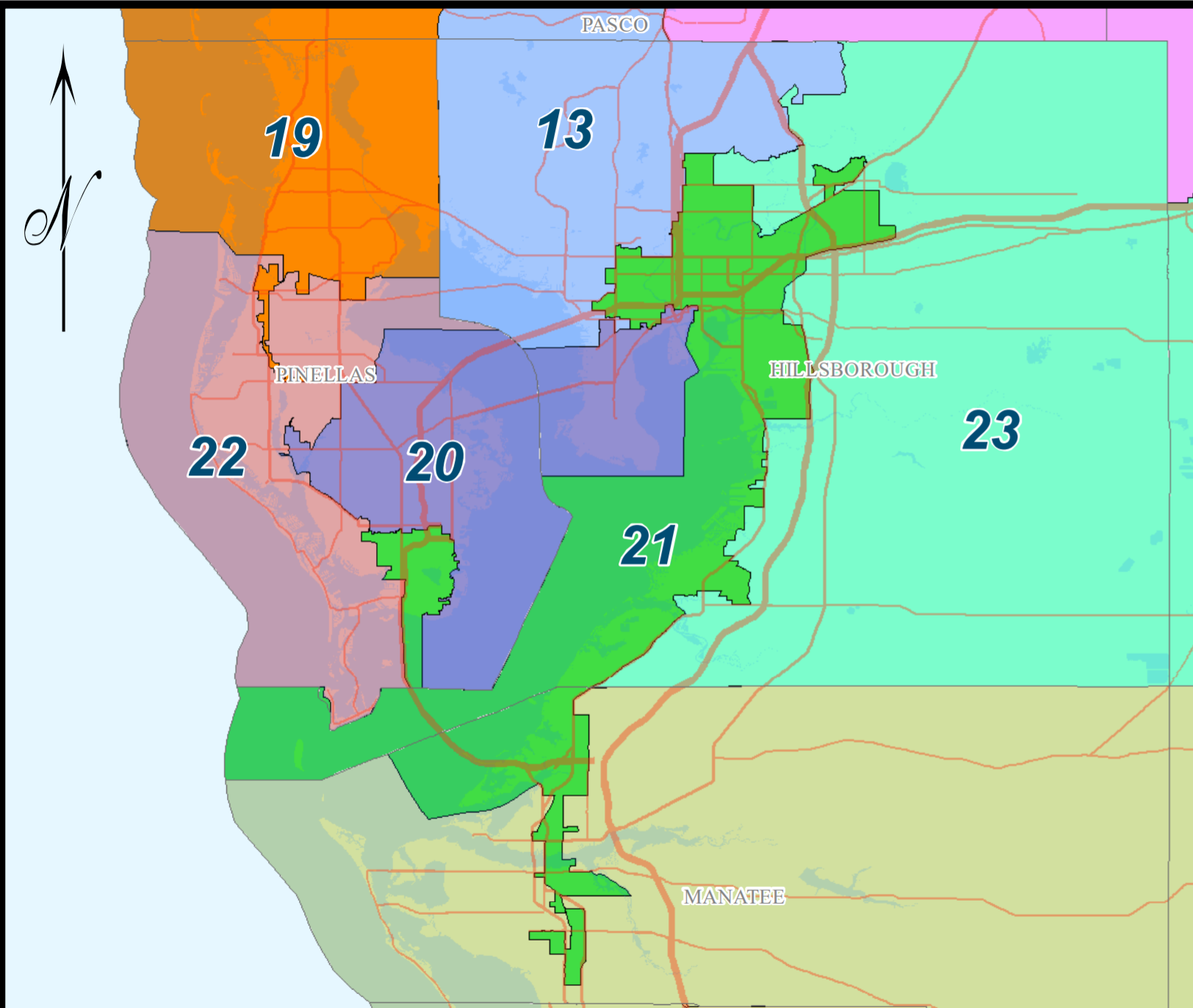

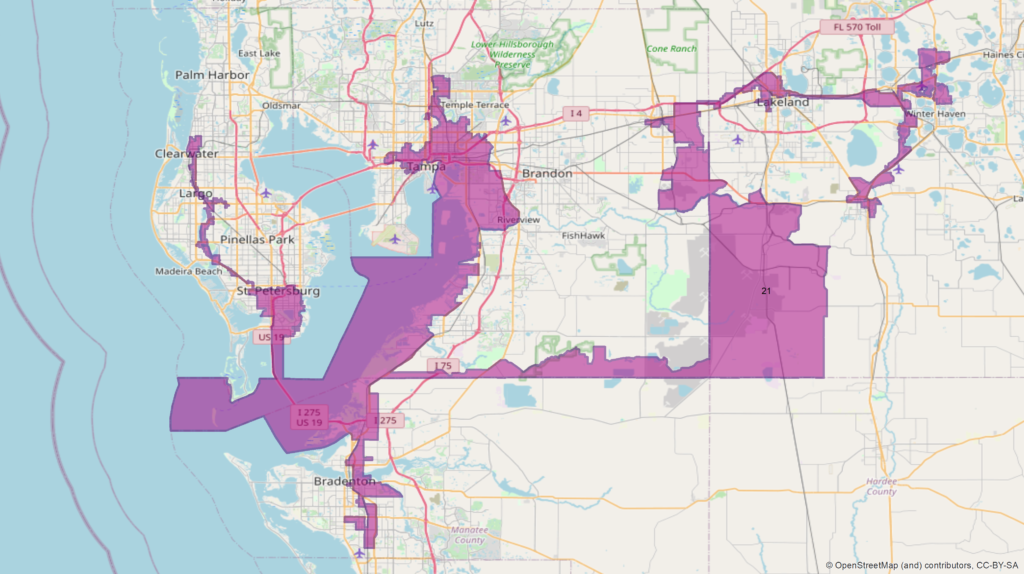

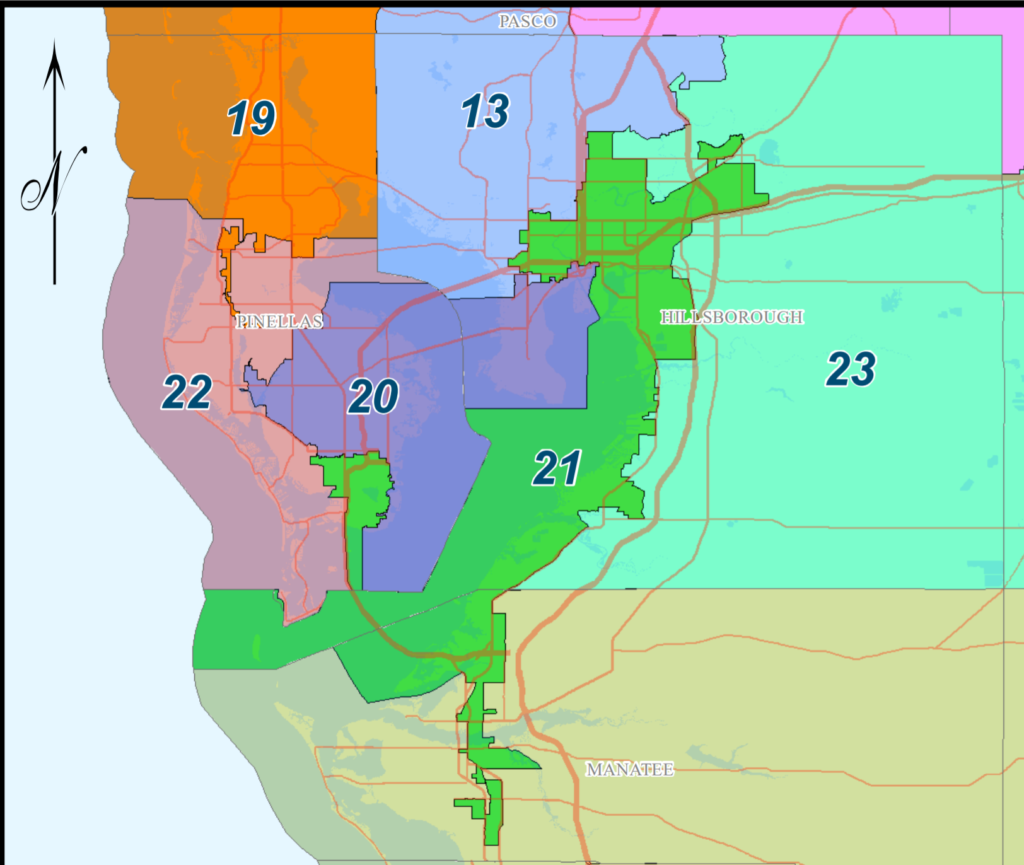

To make things even more confusing, it wasn’t clear if the Supreme Court of FL or the 3-judge panel already dealing with the Congressional redistricting would take charge of the state senate plan. To try and beat the 3-judge panel, the Florida Supreme Court told interested parties to submit plans by June 22nd (a few days before the 3-judge panel would hold its own hearing). The court picked a final plan that create a 50% black (45% voting-age population) district that went all across the Tampa Bay region and into Polk County. Behold State Senate District 21.

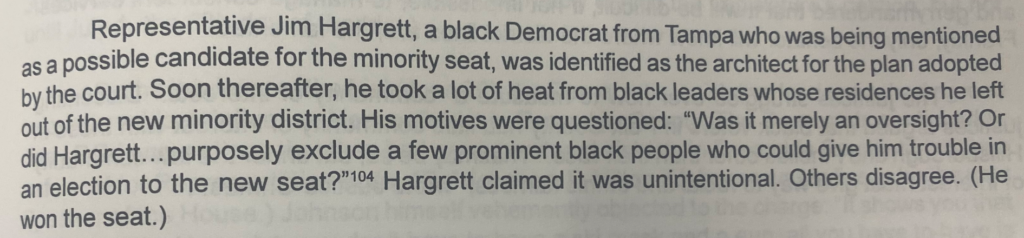

The final plan only made changes to the region effected by the district. Just a few days later, the 3-judge panel signed off on the new map. The district was believed to be the brain-child of State Rep Jim Hargrett; who apparently made sure to draft a district he would eventually be elected to by leaving out some prominent black neighborhoods in Tampa.

The Florida Supreme Court justices backed the final plan in a 4-3 decision. Justices on both sides acknowledged the bizarre lines. However, proponents of the plan said the weight of creating an additional minority district outweighed the issue of compactness.

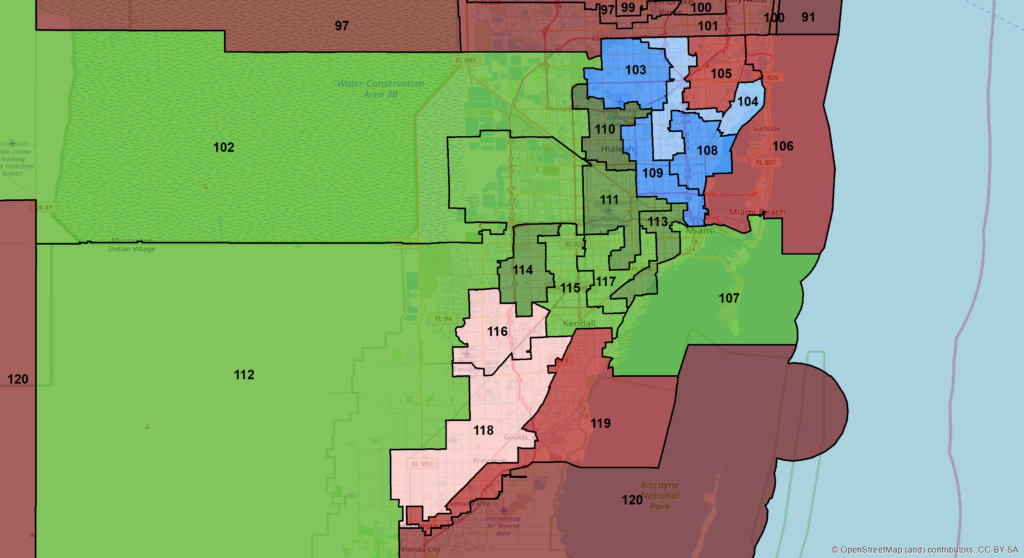

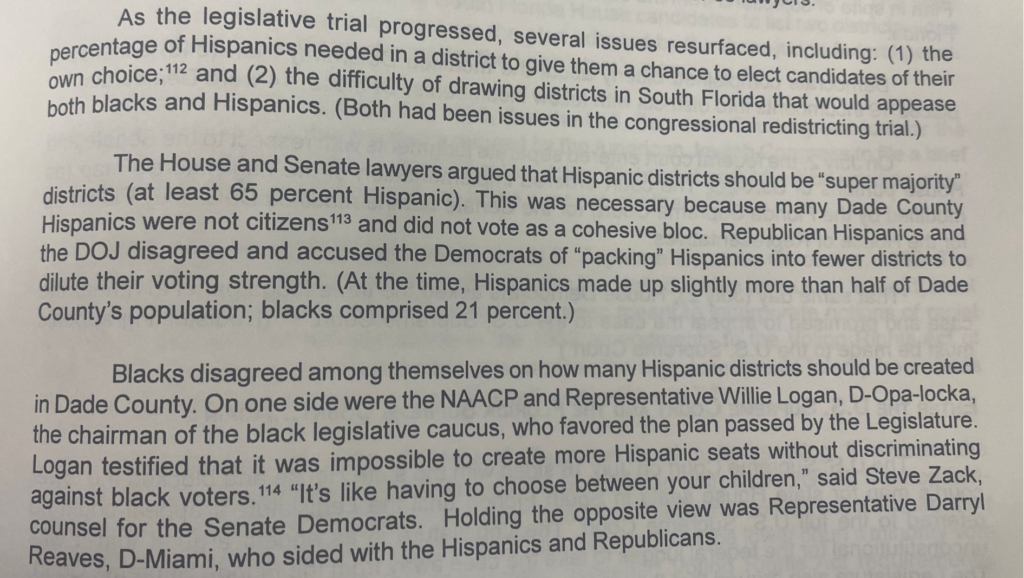

DeGrandy v. Wetherell Trial

A trial over the Miami-Dade and Escambia maps began on June 26th in the US District Court before a 3-judge panel. By June 29th, the legislature agreed to reconfigure the lines in Escambia County, but Miami-Dade was a far more complicated issue. Hispanic plaintiffs wanted 11 districts in Miami-Dade, two higher than the passed plan. The remedy was not simple. Many Hispanics were not citizens, so the question of how high the Hispanic % needed to be was a major focal point. In addition, Hispanic districts bordered several black seats. Maximizing Hispanic districts could come at the expense of African-Americans.

Proposed remedies also caused conflict among white and Jewish citizens and politicians that resided more along the coast. The trial was one that would guarantee some racial, religious, or ethnic group would end up unhappy.

Redraw Ordered – Then Reversed!

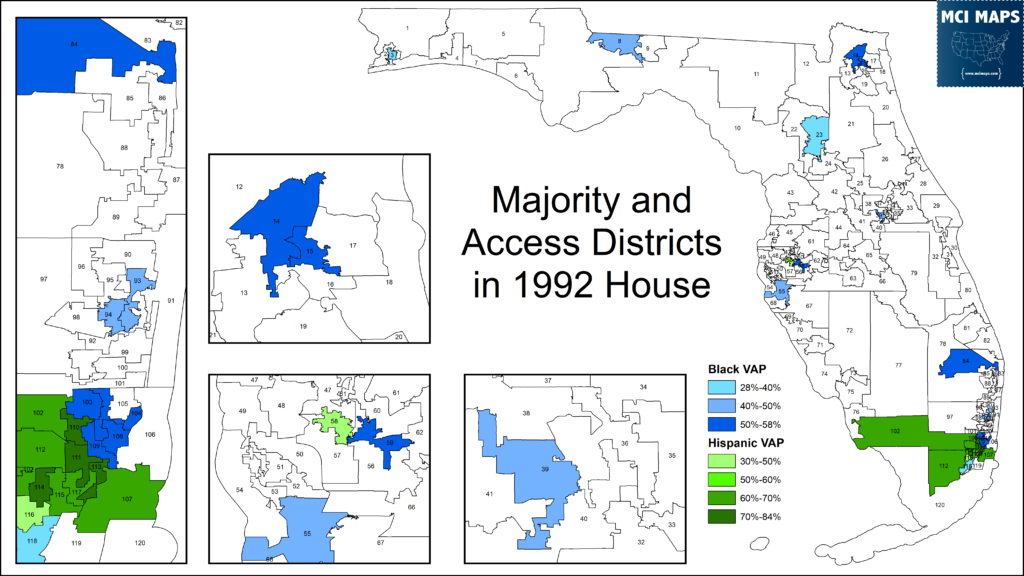

On July 1st, the court upheld the state senate plan in Miami-Dade, but struck down the house plan. That same day, a remedial plan was approved that increased the number of Hispanic districts. The plan was opposed by white democrats, but also the NAACP, and Jewish groups. The plan redrew 31 seats in the southern Florida region. Candidates began to finalize filings for the seats. However, on July 16th, the US Supreme Court STAYED the lower court decision. After several legal back-and-forth, SCOTUS affirmed that the legislative elections for 1992 would be held under the DOJ-approved legislative maps (so what the legislature originally passed, plus the new state senate configuration for Tampa).

This meant the agreed redraw in Escambia and the court-ordered redraw in Miami-Dade were NOT to be used for 1992. The late court decisions forced an extension of the filing deadlines for office. Chaos ruled the day.

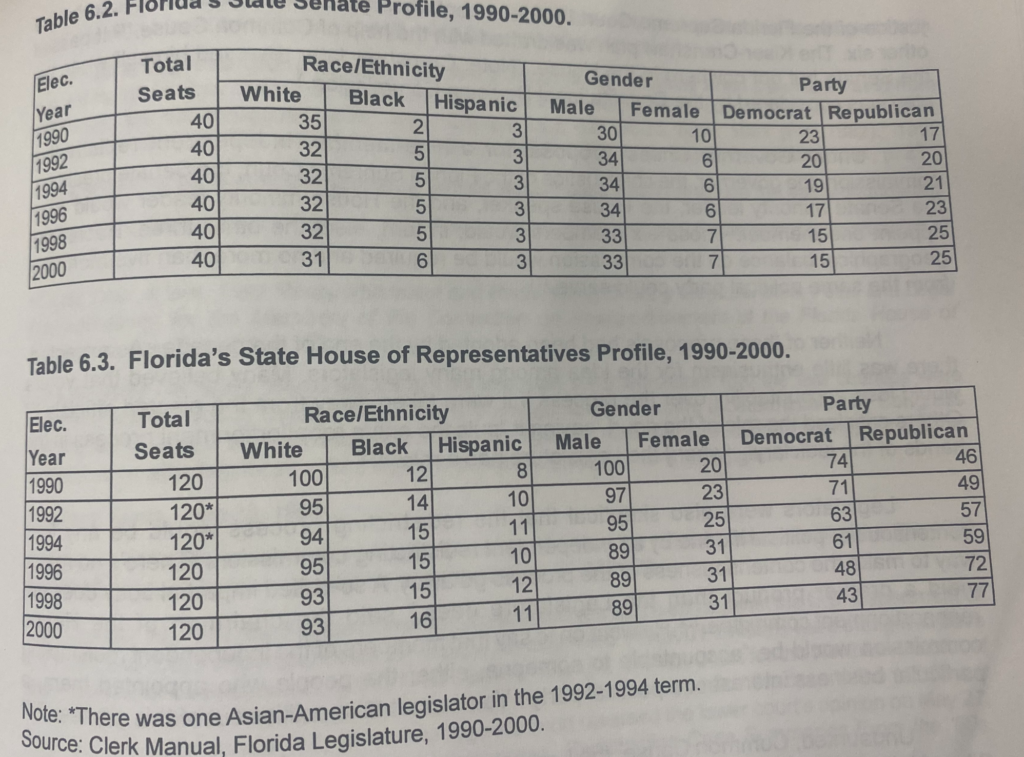

This marked the final end of redistricting pre-1992 elections. The finals plans saw a notable expansion in the number of African-American and Hispanic seats (whether majority or access).

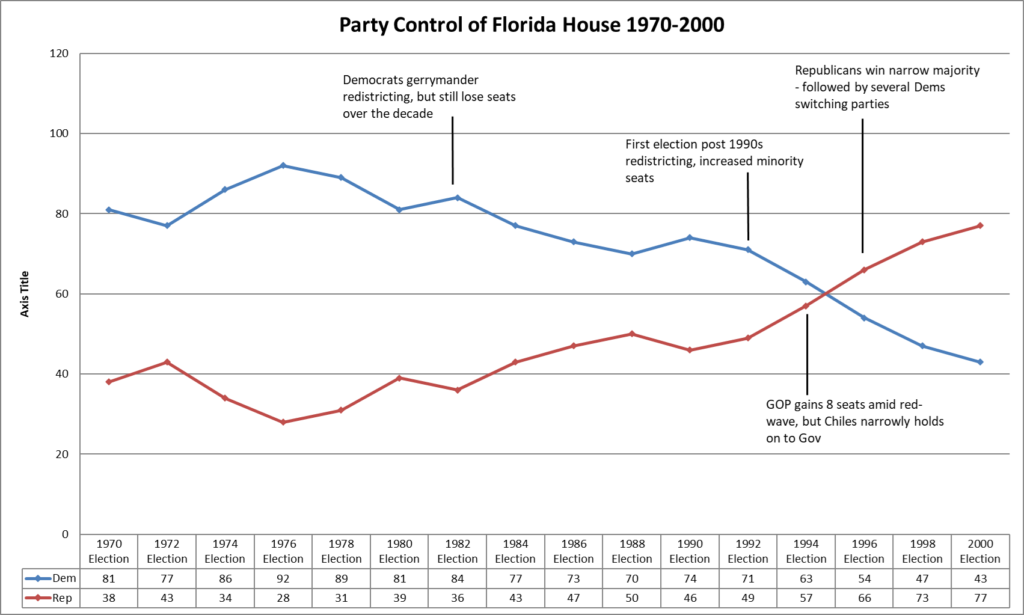

That fall, Democrats in the state house would lose 3 seats; but overall still maintained a solid 71-49 edge. The state senate would see Democrats wind up at a 20-20 tie with the Republicans.

Interactive versions of the House Map and Senate Map can be viewed in the links.

Court Cases After 1992

Johnson v DeGrandy

In February of 1993, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case over the redraw orders for Miami-Dade and Escambia. This was the case of Johnson v DeGrandy, and was closely watched by legal scholars. At the heart of the issue was to what degree any legislature had to go to maximize or ensure proportional representation of a minority group. The trick also became, how you do maximize one minority group without hurting another. SCOTUS allowed Jewish groups to file briefs for this case as well; as an expansion of Hispanic districts in Miami-Dade risked costing them representation as well.

Oral arguments were held in October of 1993, and a final ruling came down in June of 1994. The court reversed the lower court order for the redraw; thus SCOTUS upheld the state house districts drawn by the legislature and used in 1992. The court ruled that maximizing the number of minority districts was not a requirement of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The legislature was found to have drawn lines that gave Hispanic voters “roughly proportional” representation. SCOTUS affirmed the lower-court finding that the state senate lines in Miami-Dade were in line with the VRA (and that any expansion of Hispanic districts would come at the expense of African-Americans). The court cited the “totality of circumstances” – rather than any single test – in its decision.

Redraw for Senate District 21

While the DeGrandy decision was going through the courts, another district in Florida was put in the crosshairs: Senate District 21. This district had been picked by the Florida Supreme Court to meet the DOJ’s preclearance requirements. However, the US Supreme Court began taking a critical look at some of the bizarre lines coming out of district maps across the country.

Opponents of SD21 had precedent in their favor when the Supreme Court handed down its Miller v Johnson (Georgia map) and Shaw v Reno (North Carolina map) decisions. These cases struck down odd-looking districts that court found were drawn with only race in mind. In Miller, the court stated

“a reapportionment plan may be so highly irregular and bizarre in shape that it rationally cannot be understood as anything other than an effort to segregate voters based on race”

In the Shaw case, Justice O’Conner wrote that such race-based districts are subject to strict scrutiny, meaning they must satisfy three conditions: a compelling government interest, narrowly tailored to achieve the goal, and use the least restrictive means to achieve the goal.

Senate District 21 would eventually be challenged in Scott v. U.S. Dept. of Justice in federal court; with plaintiff’s believing the Shaw case gave them strong ground to stand on. Few desired a long trial, so in 1995, both the plaintiffs and the legislature agreed to try and agree on a remedial plan. Eventually a remedial map was agreed on.

A new district was drawn, one which better balanced racial minority interests with compactness and didn’t just use race as its motive for the lines (using income as well).

The new districts for the Tampa Bay were utilized for 1996 and going forward. This marked the last change in the legislative maps for the 1990s.

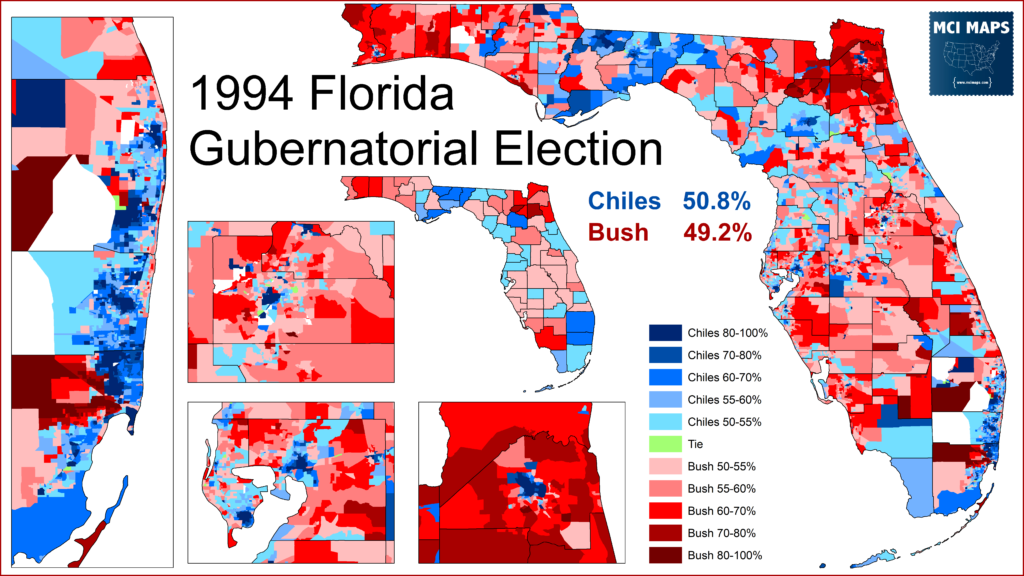

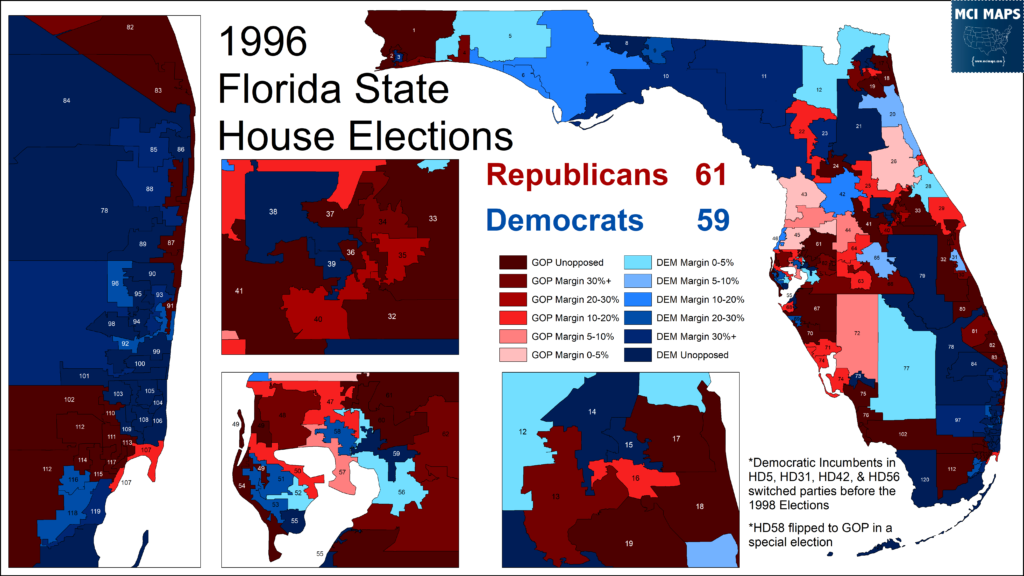

Partisan Shift in 1990s Florida

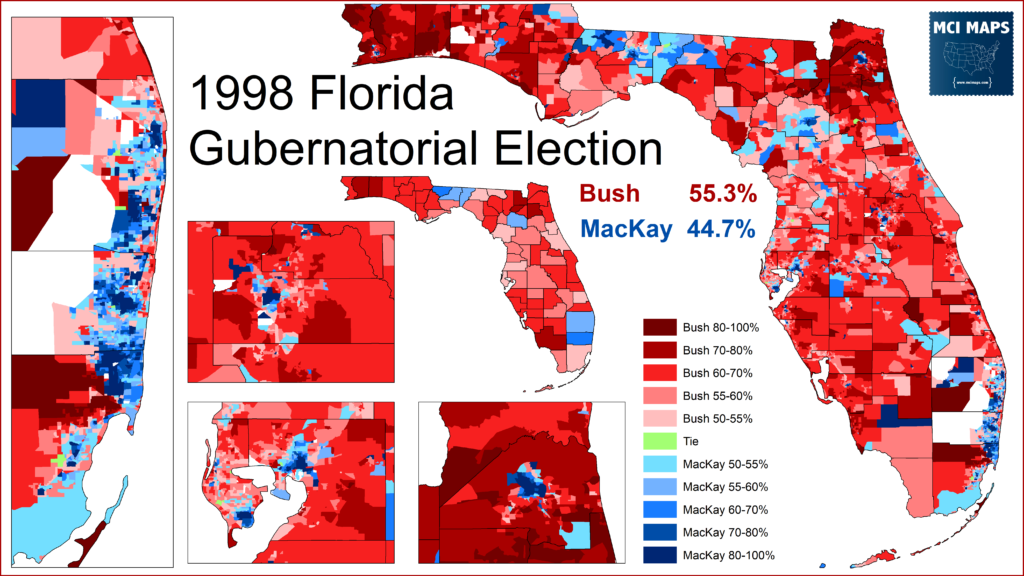

The 1990s would mark the final time Democrats held any power in Florida. The Florida Senate would slip into Republican hands the 1994 midterms, with the house falling to the GOP in 1996. Many opponents of majority-minority districts point to the lines as the culprit for the fall. However, this ignores trends that began before the new lines got underway. The State Senate was already very close, and the State House didn’t begin to trend significantly to the GOP until 1994 and 1996. The Republican takeover of the legislature came at the same time that Lawton Chiles only narrowly survived re-election against Jeb Bush.

Four years later, Jeb! would easily take the Governor’s mansion.

Republicans would finally win control of the state house in 1996. In that election, they secured a 61/59 margin; the same day Bill Clinton won 67 of the districts. The Republican win was followed by four Democratic incumbents switching parties, and another seat flipping in a special election.

Florida’s partisan shift began well before 1992, and while the VRA may have tied to the gerrymandering hands of the Democratic majority – it isn’t why the state moved further to the right. The rise in minority members of both chambers was highest in the 1992 election itself. Many GOP gains occurred after 1992.

Republicans in Florida had been on the ascendency for years; the 1990s is just when it finally culminated.

Could the white democratic leadership have saved some districts by padding them with black voters? Yes. Could they have restricted and packed Hispanics in Miami-Dade to keep more districts for themselves? Yes. Would that have been ethical? No. If it is to be argued the VRA doomed Florida Democrats in the legislature, that means it doomed their efforts to gerrymander against voter allegiances that would soon put the Governor’s office and multiple cabinet seats in the hands of the GOP.

Conclusion

The state legislative redistricting process shows how contentious and complicated the process was by this point. Legislatures and the courts would struggle to find the best way to implement the Voting Rights Act while at the same time creating districts that represented a united constituency. On top of all this was the partisan efforts of both parties to use the process to benefit their side. This situation would be even more intense in the Congressional redistricting process. Next week we will take a look at that Congressional redistricting process; and how far off the rails it got.