(This article marks Issue #2 of a history of redistricting in Florida)

Last week, I wrote about Florida’s redistricting/apportionment battles from the 1840s through the 1960s. The state’s use of counties for representation, instead of population, led to a malapportioned legislature that could get a majority elected with under 15% of the statewide vote. It took intervention from the US Supreme court to end the practice and force equal population districts. Elections in 1967 under a new map took place and in 1968 the state passed a new constitution. Redistricting from that point on would take place two years after every census and all maps would need to be signed off on by the FL Supreme Court.

This article will look at redistricting in the 1970s and 1980s, a time when Florida debated multi-member or single-member districts and minority voters fought for representation in the map-drawing process.

1970s Redistricting

Maps and Process

The 1970s redistricting process was the first held under the Constitution of 1968. The rules set out allowed for a Senate between 30-40 members, a House of 80-120 members, and allowed county/city lines to be split. The legislature would eventually adopt the first plans to divide counties to create districts. These were the first plans in Florida history to use precise population data and census districts to build the maps. For the first time, computers were used to aid redistricting in Florida. Eager to avoid further lawsuits over malapportionment, the population deviation was less than 200 people in the house and less than 2,000 people in the state senate.

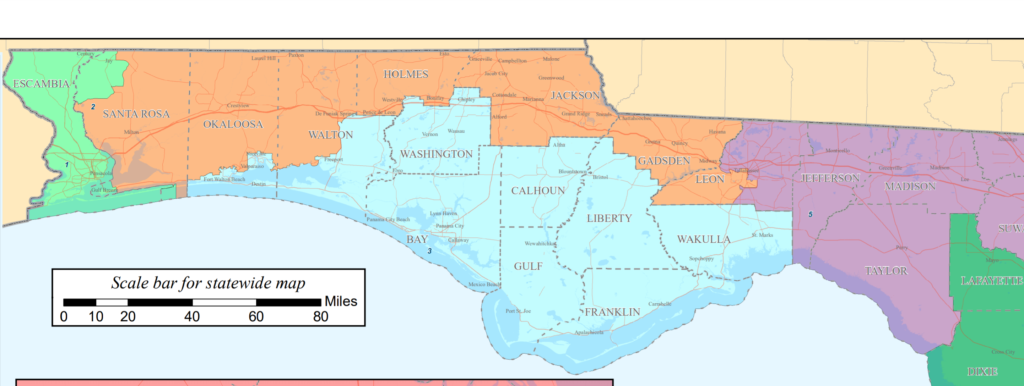

This was the state senate plan.

The house and senate products used a combination of single-member and multi-member districts.

However, while the 1970s redistricting process was fairly straight forward – that does not mean it wasn’t without a great deal of debate and controversy. Beside lawmakers going back and forth on different lines, the maps passed would eventually be challenged in court on racial discrimination grounds.

Race and Redistricting

Two obviously nefarious actions were taking place in the 1970s redistricting; political and racial gerrymandering. The Democratic majority worked to preserve its own power – using multi-member districts to restrict Republican gains whenever possible. In addition, the use of MMDs in urban areas meant most delegations were uniformly white despite representing communities with notable minority blocs. It was during this session that an alliance between the Republican minority and the African-American community would be forged for the purposes of redistricting. At the time, Florida’s black minority was just coming into its own political power. Registration was steadily increasing as the Jim Crow structures fell apart. For example, 1970 would finally see African-Americans take control of registration in Gadsden; Florida’s lone black-majority county.

Despite this growth, the number of black representatives did not rise and the white Democratic leadership showed little sympathy to the issue. The biggest focal-point in the race and redistricting debate at this time was the use of multi-member districts.

Single-Member v Multi-Member Districts

When Florida’s state legislative districts were finally passed, they were challenged by both Republicans and the NAACP. The Florida Supreme Court, which automatically reviewed maps (per the 1968 Constitution) narrowly ruled 4-3 in favor of the state. In the decision, the court made it clear it felt the use of MMD may be demonstrated to diminish minority strength, but that the evidence at the time was not there. A federal suit was filed in Wolfson v Nearing; but the court rejected the complaints. Courts would eventually come around the the point of the NAACP, but in the meantime the 1970s the maps stood.

The statements from politicians at the time demonstrate a tremendous amount of privileges and arrogance. Miami-Dade State Senator George Firestone said, on the prospect of single-member districts in his county

[We’d be replaced by] “a senior citizen representative, a black community representative, a condominium representative, and a Cuban-American representative”

December 12, 1976 Tampa Bay Times newspaper

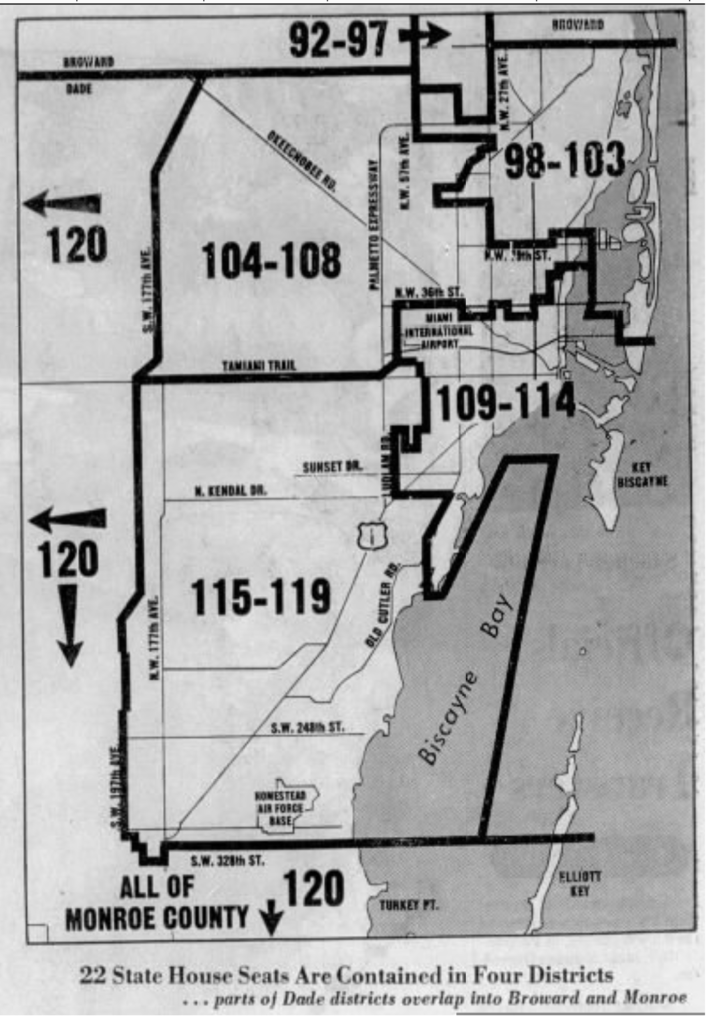

Miami-Dade county itself had been divided up into 4 large multi-member blocks. The white representatives argued the minority voting blocs could “influence” multiple districts instead of controlling a handful.

It is notable that multi-member districts were specifically used in urban (and diverse) areas while rural communities were more often the locations of single-member districts.

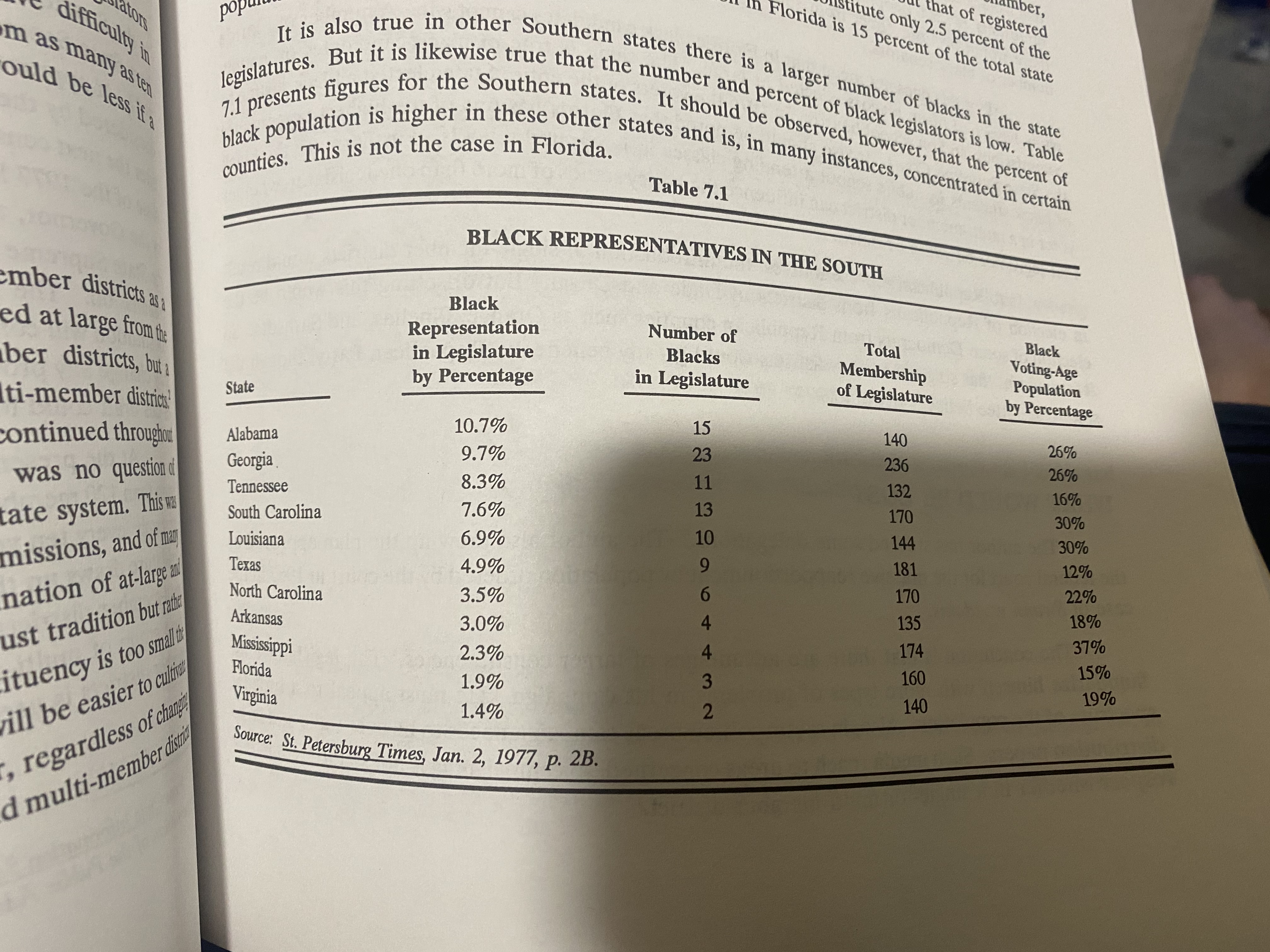

As the 1970s dragged on, the issue of racial voting power and MMDs continued to brew. Florida lagged in black state representatives compared with the rest of the former Jim Crow south. In 1977, only 3 black state representatives were elected in Florida, with 0 state senators. John Lewis himself commented on the problems of Florida’s minority representation.

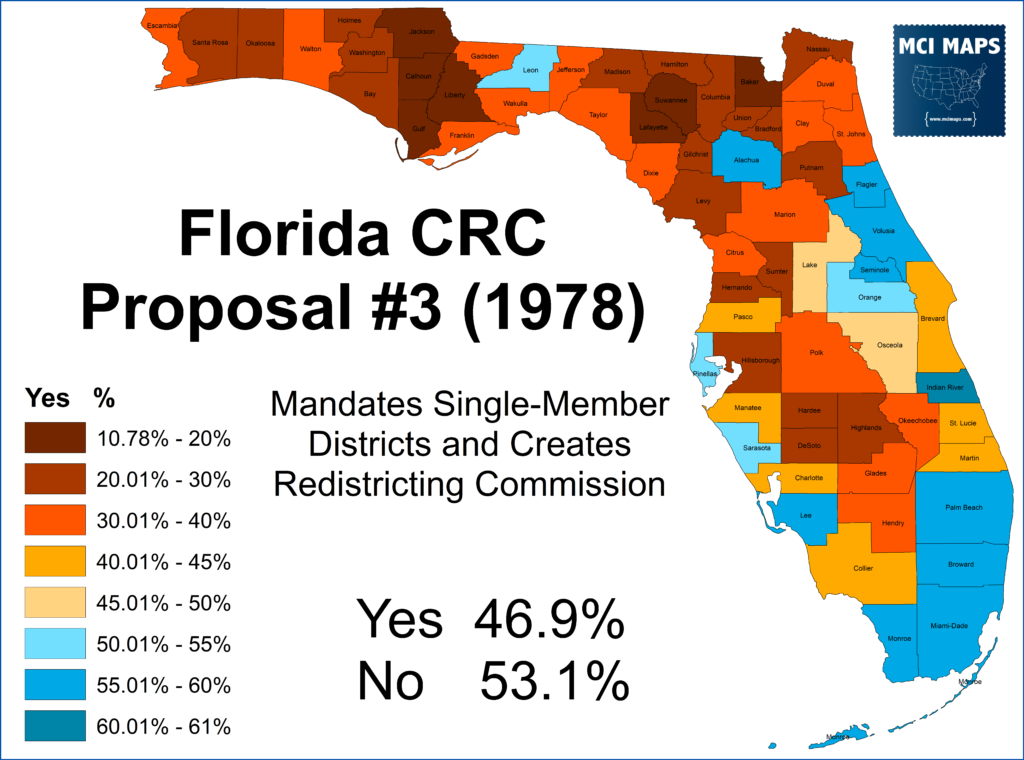

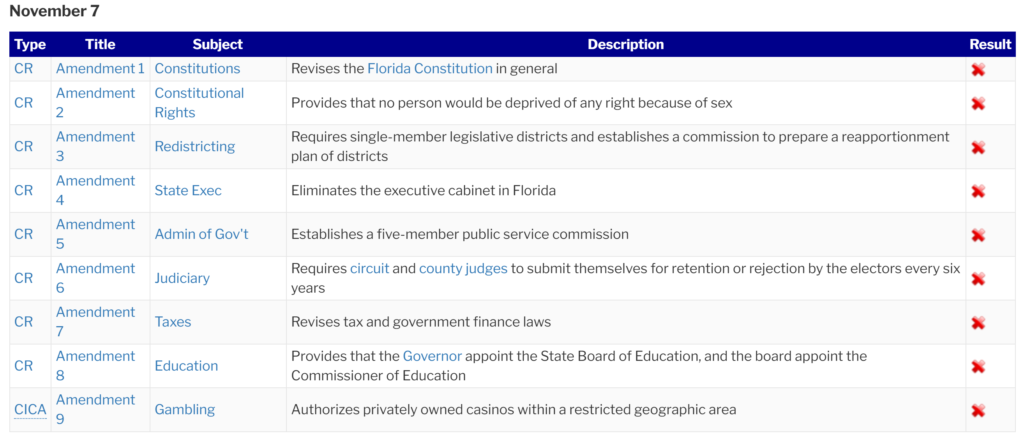

Reform-minded Governor Rubin Askew gave his support to ending MMDs; and in 1977 the Florida Constitutional Revision Commission began to meet on possible reforms to put before the voters. One proposal to come out of the CRC was a ballot measure that would created an independent redistricting commission and eliminate multi-member districts. The measure had broad political support. By the late 1970s, many politicians knew multi-member districts were likely to be killed-off in the 1980s redistricting, and few wanted to defend the MMDs or gerrymandering in the papers. However, the measure failed at the ballot, along with every other proposal from the CRC.

The measure’s failure was heavily influenced by North Florida opposition – but it also failed to generate the landslide numbers it needed in urban counties. The proposal likely got swept up in an overall opposition to multiple Constitutional Revision Commission proposals.

The most contentious ballot measure was a proposal to expand casinos in Florida; something rarely population with Florida voters. It is believed that measure, which was put on the ballot via citizen initiative, overshadowed debate on the redistricting reform measure and other proposals.

An effort to get a similar measure on the 1980 ballot failed to get the signatures it needed.

The measure may have failed, but the trend against multi-member districts was growing. Through the 1970s, courts had begun reviewing the use of MMDs and at-large elections and evidence was mounting the system of MMDs did hurt minority representation. With the Florida debating getting more heated, lawmakers saw the writing on the wall and announced 1982’s redistricting would utilize entirely single-member districts.

1980s Redistricting

Background

By the 1980s redistricting sessions, the fight over single-member vs multi-member districts had already come to an end. The legislature held a listening tour across the state and found a vast majority of the public wanted SMDs. With any effort to preserve MMDs seen as unlikely to succeed, supports of the practice caved. The redistricting process would largely be regarded as an open and transparent process. However, the process was not without controversy or debate. The House and Senate would eventually clash over redistricting issues. In addition, the demand to draw minority-favored districts would lead to efforts to meet those mandates while also protecting white incumbents.

Partisan Efforts

When the 1982 redistricting got underway, the Democratic majority was not seriously at risk. Over 60% of registered voters were Democrats. Democrats had a large 81-39 majority in the house and 27-13 majority in the senate. On top of this, all Cabinet offices and the Governor were Democrats. However, this strength did not mean efforts to protect Democratic incumbents were not put forward. These efforts stand out the clearest in the Senate – where the divide over redistricting was much more evident than the house. The Senate democratic caucus was divided between Senate President W.D. Childers and Senator Dempsey Barron; a conservative Pork Chopper from Bay County. Barron was chairman of the redistricting committee for the Senate and he aimed to create an ideological gerrymander to protect conservative Democratic incumbents wherever possible; while also acknowledging minority districts would be increased.

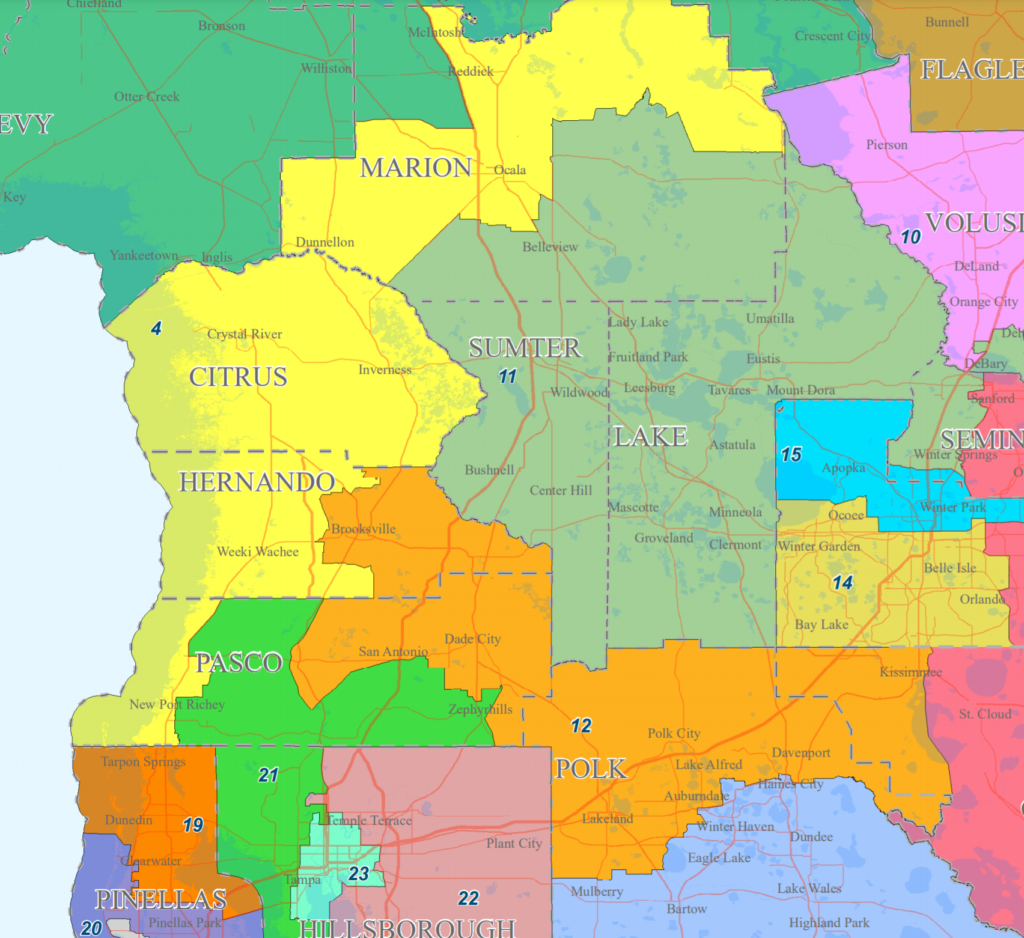

All three chambers were drawn to try and protect the Democratic majorities, but the Senate map by far as the most obvious bizarre lines. Though the House has plenty of stand-outs.

The Congressional map saw some flare-ups between the delegation and ambitious lawmakers. Members of the delegation, including non other than future-Senator Bill Nelson, had to work to keep as much of their bases in their districts as possible.

The Push for Minority Representation

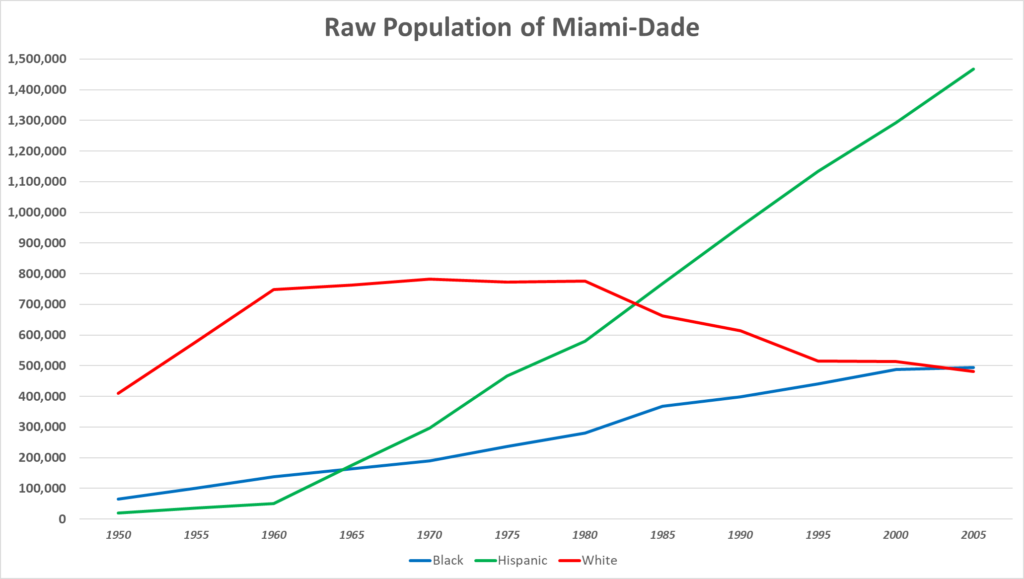

As the 1980s redistricting got underway, it was acknowledged by everyone involved that minority districts would be a priority. The 1970s saw multiple court cases on minority representation in legislatures and Florida already trailed other states. At the time, only 5 black members were in the Florida House, and just one Hispanic member. Congress was in the process of amending the Voting Rights Act, something that would have massive implications in the 1990s redistricting. Florida was also growing more diverse, especially in the south Florida region. Dade County alone was seeing a massive increase in Hispanic and Caribbean populations – something that would continue through the 1980s.

This massive shift in Miami-Dade County was fueled by refugees as well as traditional immigration – something I covered in my Substack Newsletter. This ethnic shift in southeast Florida, as well as the activation of black voters who’d been long suppressed by Jim Crow, would put tremendous pressure on the legislature to create minority districts.

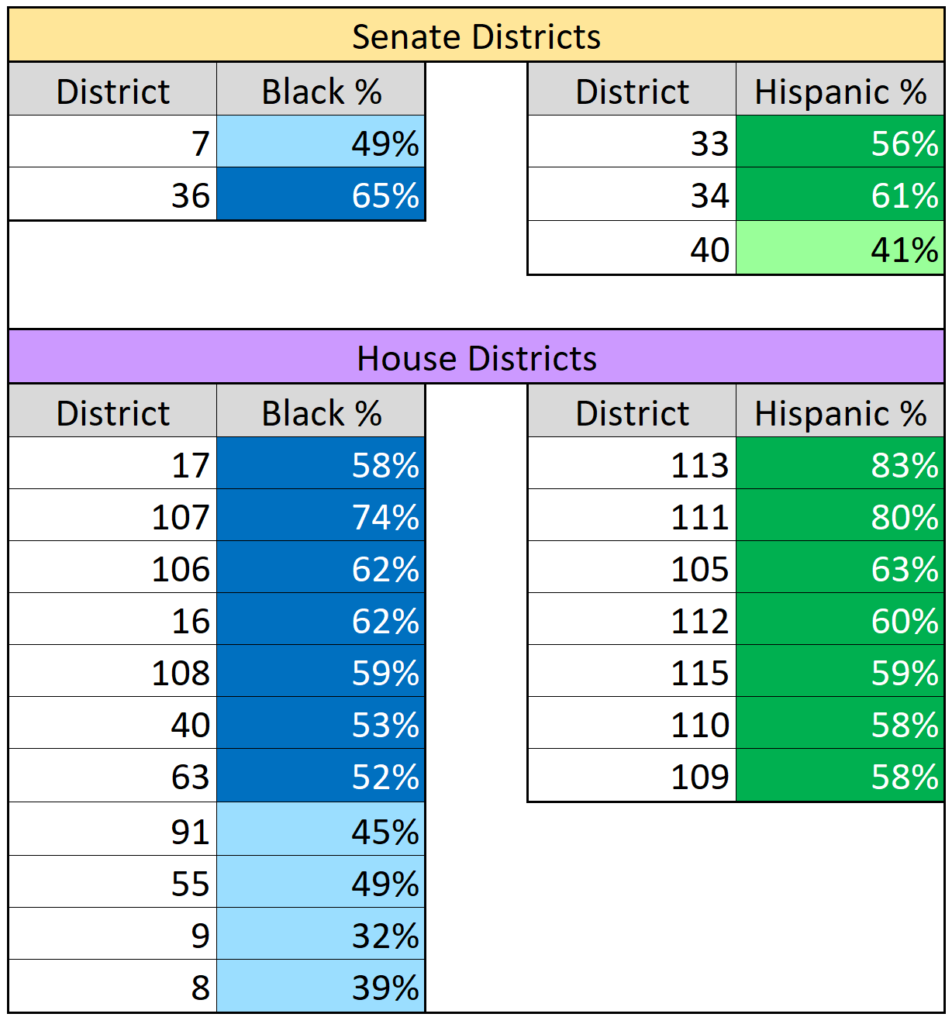

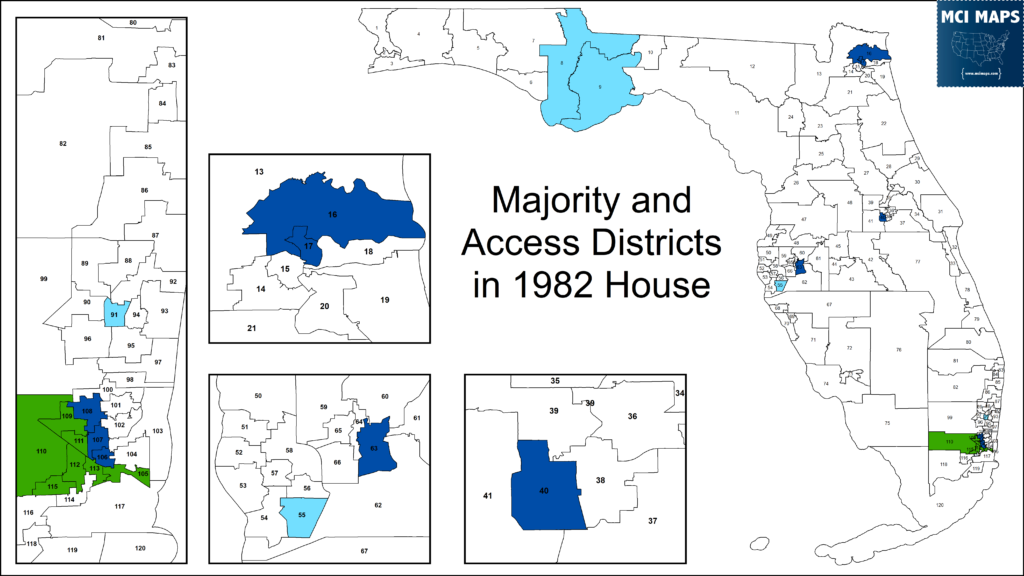

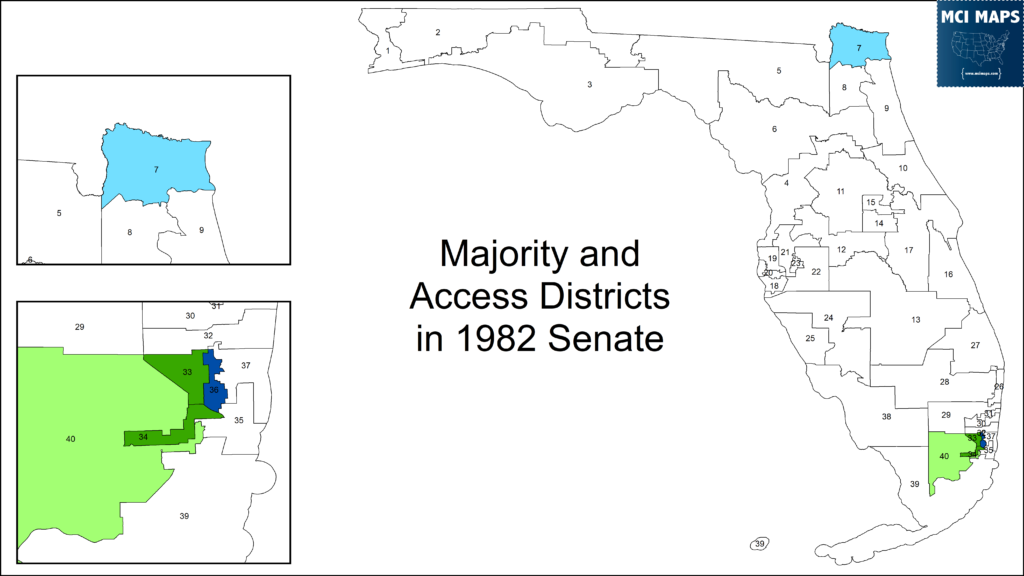

The legislature underwent what was referred to as “Affirmative Gerrymandering” – a process of drawing districts to create minority districts. The legislators aimed to create both minority-majority districts and minority-access districts. Access seats were largely viewed as seats with 30% of more of the population being minority (sometimes 25% is used). The final legislative plans came out as

- House Plan: Seven black-majority districts, four black-access districts

- House Plan: Seven Hispanic-majority districts, no access districts

- Senate Plan: One black-majority district, one black-access district

- Senate Plan: Two Hispanic-majority districts, one Hispanic access district

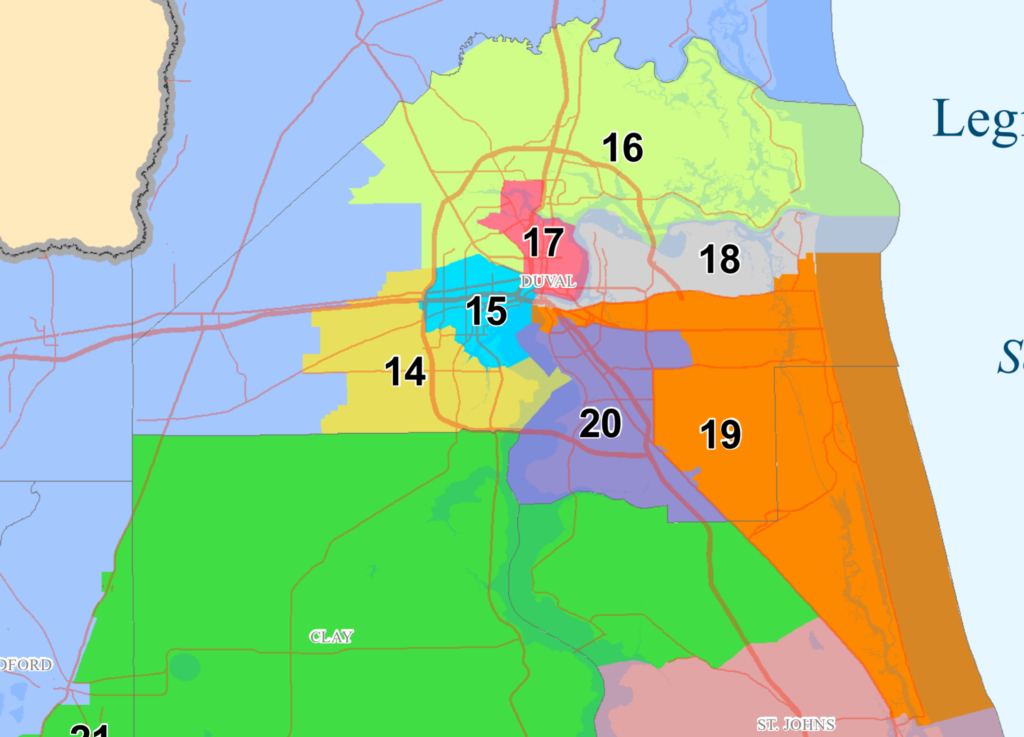

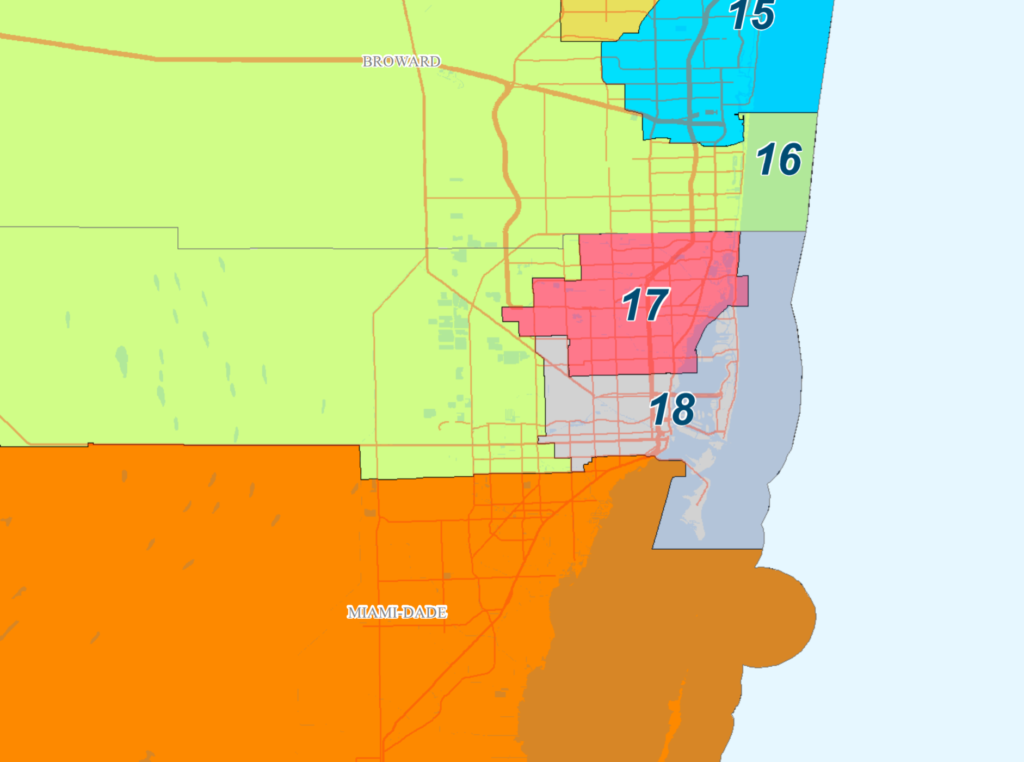

On the Congressional side, the delegation map remained heavily white. Talk of creating a black-access seat in Tampa never got past the committee phase. A Hispanic majority (51%) district was create in Miami-Dade county: the 18th.

This seat was held by Democrat Claud Pepper, who’s popularity with Hispanics prevent him from losing his seat. When he passed in 1989, a huge ethnically-driven fight took place for the district; ultimately ending in the election of Congress’s first Cuban-American, Republican Ileana Ros-Lehtinen.

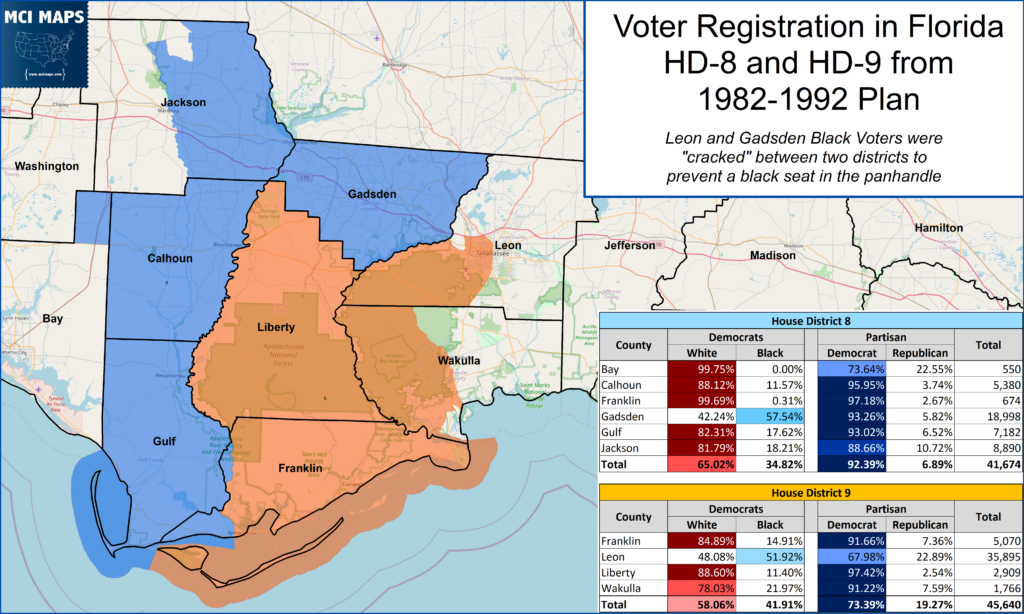

1980s Cracking Example

While the 1980s maps would be a major improvement for racial representation, the efforts to “crack” (divide) minority voters is still evident in places. One of the clearest examples was in the panhandle. The state house plan created two “access” districts in and around the Tallahassee region, but this was done instead of creating a true black-majority (or close to majority district). The NAACP and local black leaders wanted a district connecting Tallahassee’s southside black population with the majority-black Gadsden County. Instead, the 8th and 9th were drawn to split the southside and Gadsden and put them in with heavily white, rural voters. Both the 8th and 9th were right around 31% black, technically access districts.

The legislature got to claim it was creating “access seats” but it was paring black voters with rural/white voters in North Florida.

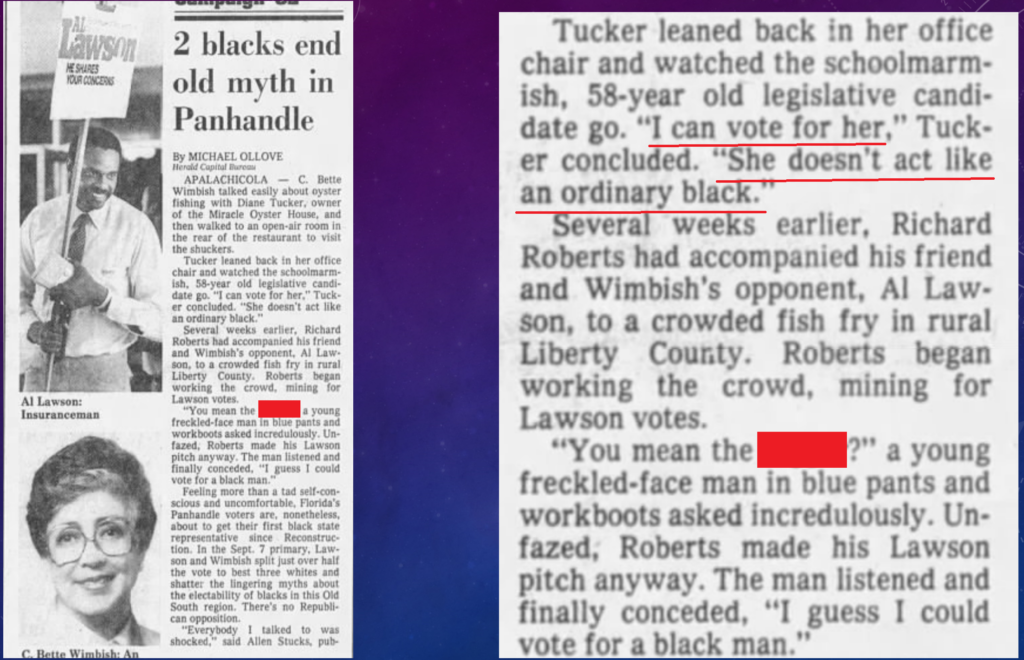

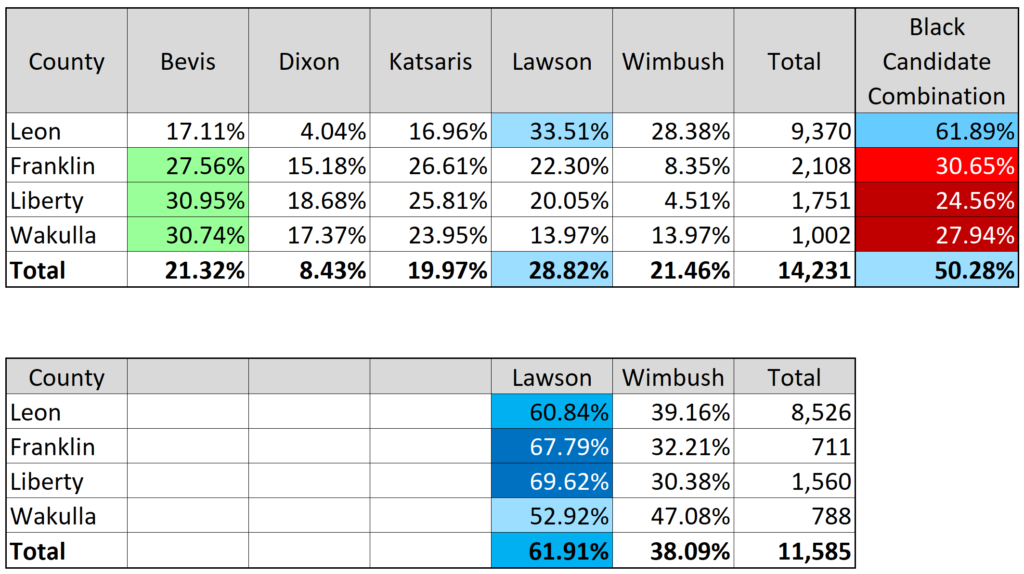

Undaunted, black voters in Tallahassee would work to take the 9th district. This district would see a 5-way Democratic primary that, thanks to three white candidates splitting the vote, saw a runoff of two African-Americans; Al Lawson and Bette Wimbush. The white vote split was part of the story – but another factor was the strength of black turnout. The Tallahassee black population galvanized to get the vote out for Lawson and Wimbush; in the end getting 40% turnout compared to the 30% average among white voters.

Lawson would win the runoff, becoming the first panhandle African-American representative since reconstruction. However, part of this was only thanks to avoiding a white v black runoff — and forced two black candidates to campaign in objectively racist rural populations.

Both candidates were from Tallahassee, but Lawson was able to dominate in the rural portions in the runoff – campaigning as a more moderate and business-friendly candidate while Wimbish was a more regular liberal.

Lawson’s success was impressive and was heavily touted. However, it does not change the fact the district was born out of cracking black voters. Lawson would represent the least black district by far of any of the newly-elected black representatives.

Effects on Minority Representation

The 1980s redistricting session would overall yield a notable increase in minority representation. African-American membership doubled from 5 to 10. Hispanic membership went from 1 to 4 in 1982, but increased to 9 by the end of the decade. Multiple districts would be marked as either minority-majority or minority-access.

Over the next decade, Florida would continue to grow in diversity. On top of this demographic shift, a new version of the Voting Rights Act would be passed and multiple Supreme Court cases would be issued on the subject of race and voting/redistricting. This would all combine to make the 1990s redistricting process in Florida a titanic battle.

Conclusion

Race and redistricting began to bubble up as a bigger issue in Florida in the 1980s. The issue would dominate the 1990s redistricting process in the state – coming at a time when the Democratic majority desperately tried to cling to its power. Next week’s article will cover the 1990s dynamics as well as the state legislative redistricting process. An article following that will cover the Congressional fight of the 1990s. That’s right, the 1990s are so complicated that it will take two articles. Buckle up. The 1990s process was more complicated that you know.