(This article marks Issue #1 of a history of redistricting in Florida)

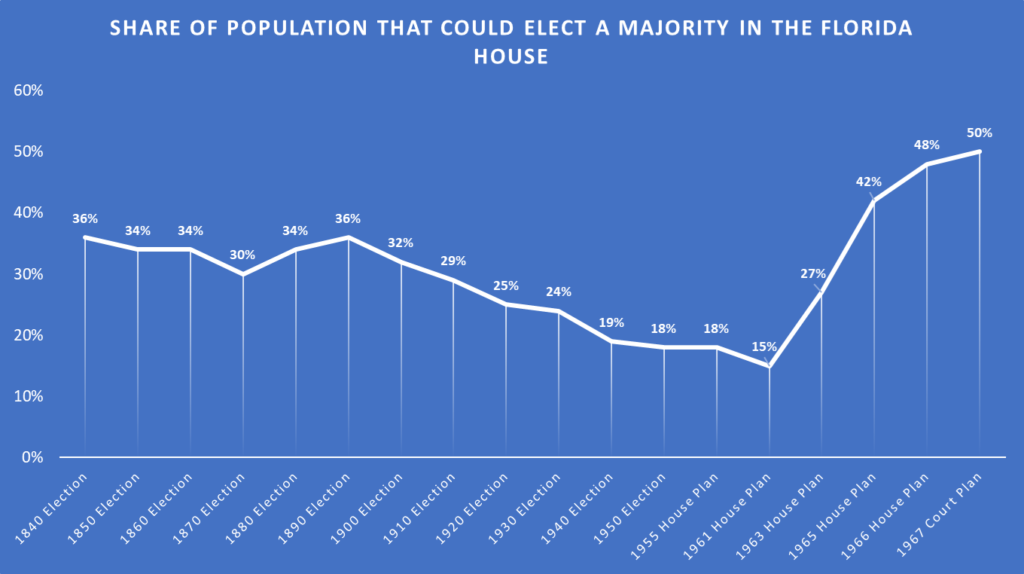

Redistricting has been a contentious issue in Florida since its 1845 statehood. However, while we tend to think of redistricting as something involving equally-populated districts, many states used to organize their state legislatures in a very different manor. Until the 1960s, many states designed their state legislatures around county boundaries – giving little consideration to population. These legislatures would operate similar to the US Senate – which affords all states two Senators. States like Florida treated their counties as mini states; guaranteeing representation and limiting the power of larger counties. Lawmakers argued these systems ensured one region of a state wouldn’t dominate a legislature. However, growth in urban centers over time meant Florida, as well as many other states, had some of the most malapportioned legislatures in the nation; with under 20% of the population able to elect a majority in a chamber. It would take the US Supreme Court to bring an end to these malapportioned legislatures. This article will look at how this process played out in Florida.

Malapportionment from the Beginning

The Original Maps

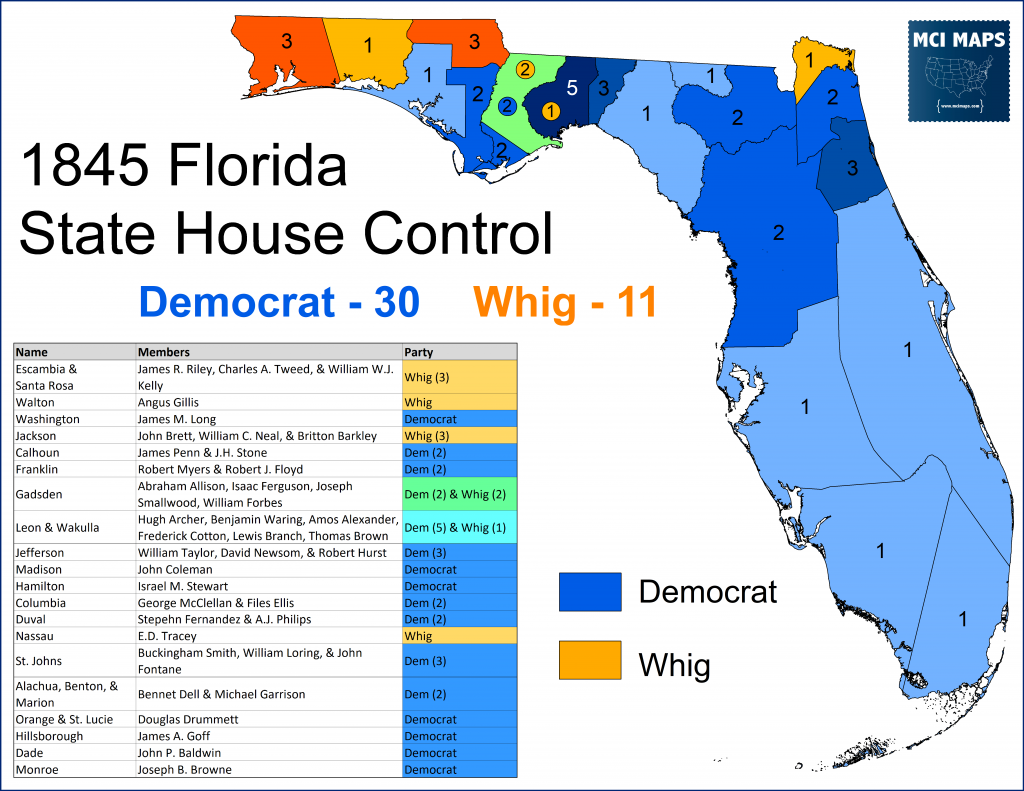

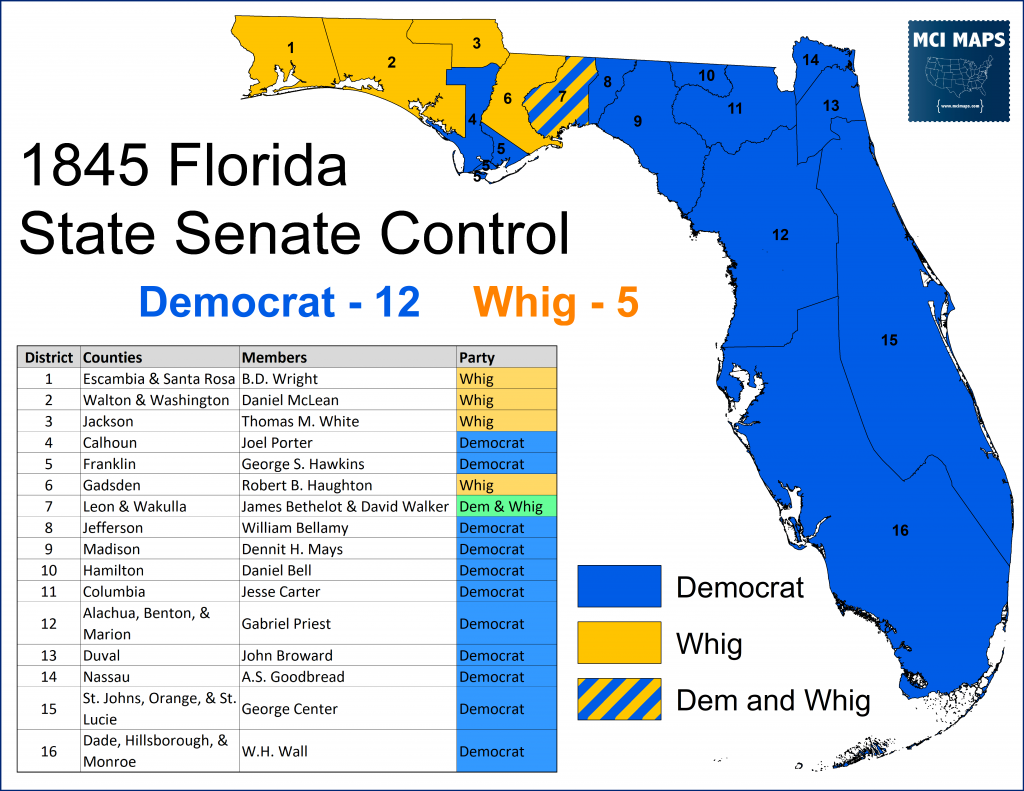

When Florida became a state in 1845, it was governed by the 1838 Territorial Constitution. This document gave every county a state representative, with the maximum number of representatives capped at 60. After each county got its seat, the remainder seats could be divided up among the larger populated counties based on a ratio approved by the legislature. Senatorial Districts could be multi or single county and could not total more than 1/2 the state house total. The first statehood elections were for a 41 member State house and 17 member State Senate.

The constitution did not allow counties to be divided into districts. Counties with multiple members would hold elections for the assorted “groups.” This insistence on counties using at-large elections for the state legislature would remain until after the 1968 Constitution.

At this point, 35% of the population could elect a house majority; and just 28% was needed in the senate. These totals were never changed for the life of the 1838 Constitution and carried into the Civil War. The Confederate Constitution for Florida maintained the same system. Florida’s constitution would be rewritten, however, after the Civil War.

Reconstruction Constitution of 1868

In 1867, Congressed Passed the Reconstruction Act, which ordered former confederate states (except Tennessee) to be reorganized into five military districts and new constitutions being set up that conform with the 13th and 14th amendments. General John Pope ordered delegate elections for a new constitutional convention, which subsequently met in January of 1868. Of the 46 delegates, 18 were black and 28 were white. A coalition of black members and radical republican white members made up a majority; known as the “radicals.” A faction of “moderates” – made up largely of white planters and business interests, were a minority at the convention. Once the “moderates” realized they were a minority at the convention, they tried to delay the actions of the body for weeks as they plotted with former Confederates to overthrow the leaders.

Apportionment became a major fight at this convention. The “moderates” wanted a system that gave equal county weight – a system that would benefit the small but numerous rural, white counties. The former plantation counties, many now with voting black majorities, were the biggest voting blocks in the state. As such, the “radical” faction at the convention favored apportionment with more of a population emphasis. The fight over apportionment by county vs population became a def-facto fight between black and white.

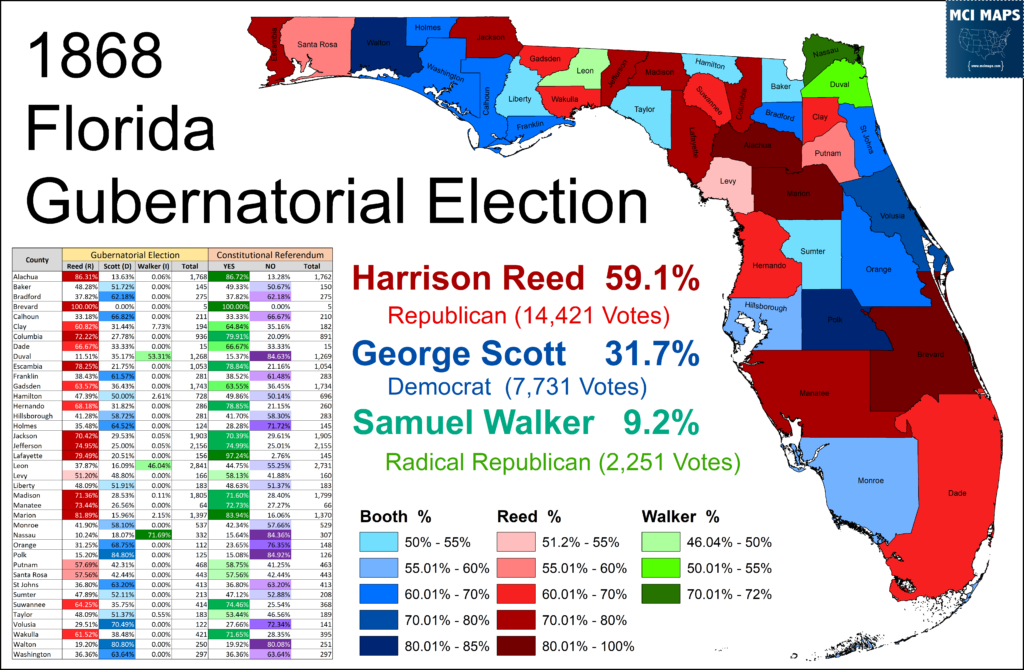

The “moderates”, realizing they couldn’t win fairly, left the Tallahassee convention and travelled to Monticello, some 25 miles away. There, they passed their own constitution, which gave each county one state house member and allowed a county to have an additional member for every 1,000 registered voters (not census count). No county could have more than four members. The State Senate would be single-member districts and supposed to be equal in population “when feasible.” The “moderate” faction then returned to Tallahassee, kidnapped two “radical members” in order to get a quorum, went to the convention hall at night, and “passed” their constitution. This was all done with the aid of federal troops stationed at the capital. Eventually the “radical” majority was able to pass its own constitution, but the reconstruction committee in DC picked the “moderate” constitution. Future Governor Harrison Reed, a moderate Republican politicians, wrote…

“Under our Constitution the Judiciary & State officers will be appointed & the apportionment will prevent a negro legislature.”

Harrison Reed, moderate Republican future Governor, in a letter to former Confederate Democratic Senator David Yulee

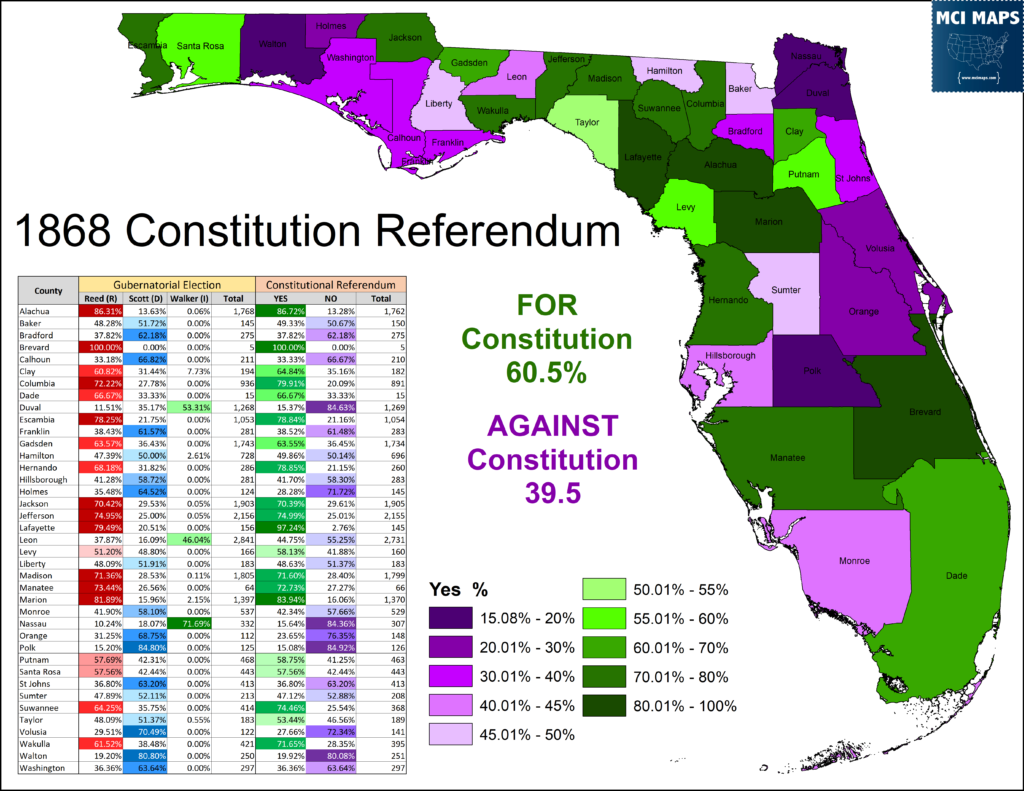

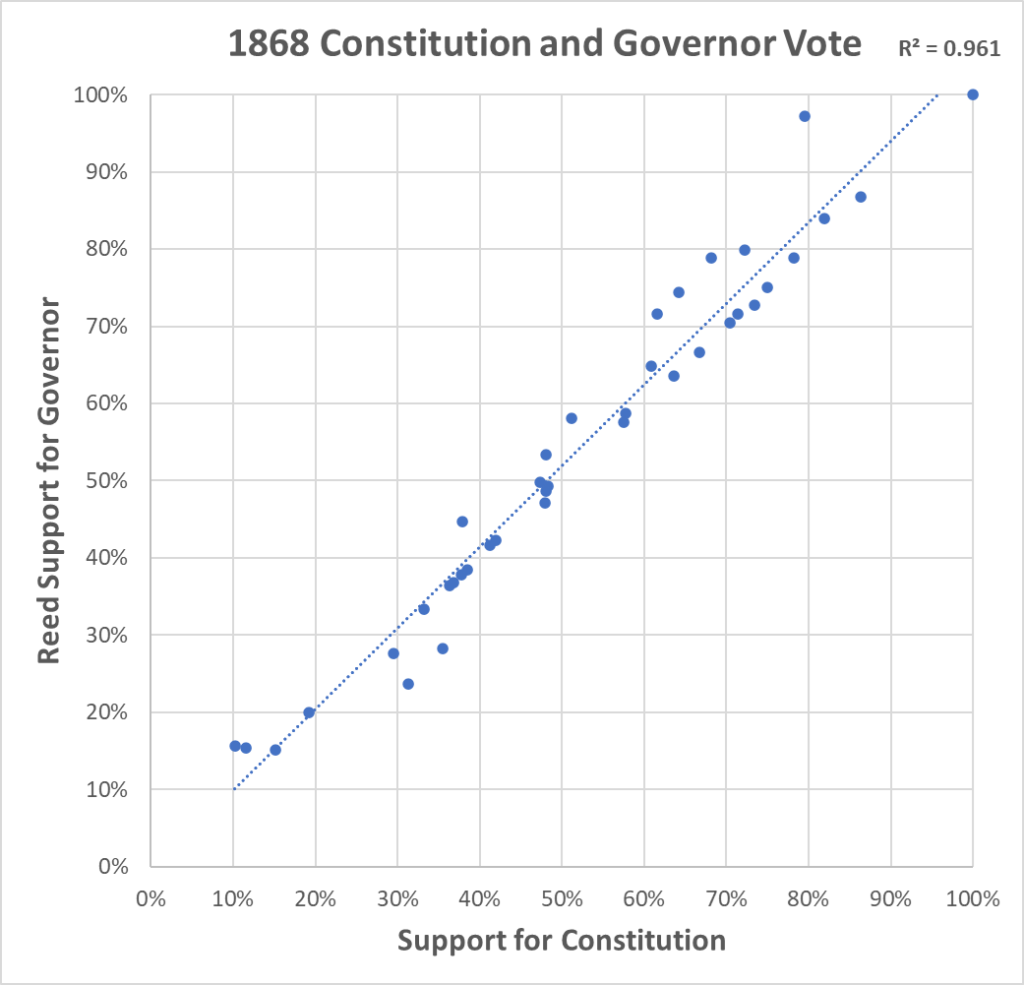

The vote on the Constitution would take place in May of 1868. That same day, Reed would win the Gubernatorial Election, defeating Confederate George Scott and radical Republican Samuel Walker. Black voters in populated counties like Leon and Duval supported Walker’s campaign.

The constitution passed with a similar percentage as Reed. The returns show that Reed and the Constitution had near-identical support. The opposition to the constitution largely came from ex-confederates who hated its rights for freed slaves, and urban black voters hated the apportionment provisions. Rural black voters were more in favor of the apportionment plan, and hence gave the constitution, and Reed, their support.

The ordeal proved that many reconstruction supporters did not favor true Democracy if it meant black rule – and apportionment was a key way to prevent it (even while giving black men the right to vote). This apportionment system would remain in effect until the 1885 constitution. The system allowed only 1/4 of voters to elect a majority of state senators, with 1/3 able to elect a state house majority.

Jim Crow Constitution of 1885

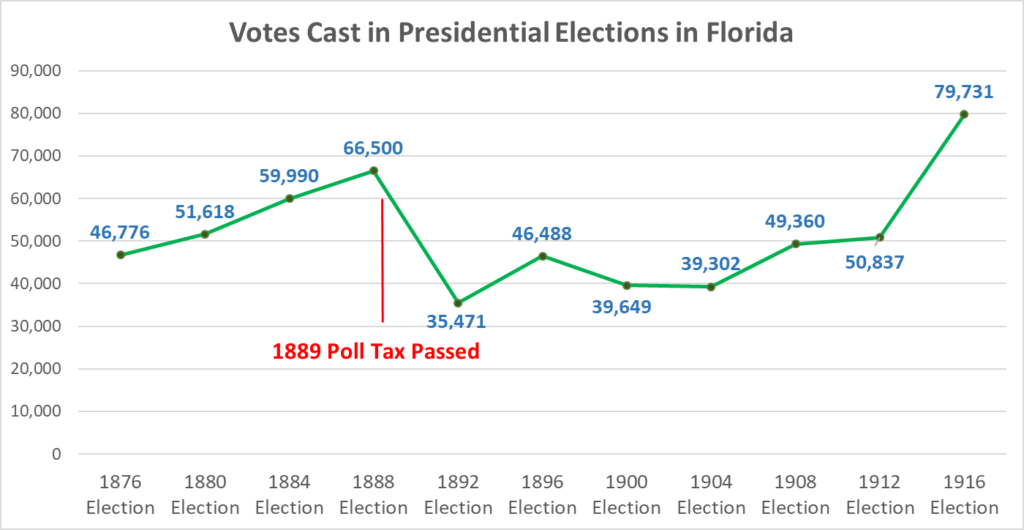

In 1885, after white Democrats took full control of Florida in the post-reconstruction era (using violence and intimidation), another constitutional convention was organized. The convention passed a new constitution to officially bring Florida into the era of Jim Crow. The constitution codified racial segregation and allowed the passage of a poll tax. The poll tax caused turnout in Florida to crater.

Apportionment was also tweaked, with each county getting one state representative and not allowed more than three. A state house of 68 and state senate of 32 was set up and remained malapportioned. The state entered the era of single-party rule. However, the growth of populations in urban centers would begin to crow, furthering the malapportioned of the legislature and brining white politicians from rural and urban counties into conflict.

Rise of the Pork Chop Gang

Legislative Heartburn over Redistricting

In 1900, Florida voters approved an amendment that ensured every time a new county was added, it automatically got one state representative. By 1915, Florida had added so many counties that the state house had exploded past the 68 member limit – and currently sat at 73. This meant reapportionment would require members losing seats. As a result, the legislators, eager to preserve their power, failed to reapportion and rather submitted an amendment to the voters to change the formula again. This tactic began a long trend for the next several decades. The legislature would delay, and when finally pushed, would send a measure to the voters. Even if the amendments failed, the process acted as a delaying mechanism to any change.

- 1916 Amendment – Would give each county a state senator and at least one state house member. Counties maxed at 3 state house districts. Failed 37%-63%.

- 1922 Amendment – Would have a Senate of 38 members and each county getting between one and four state house members. Failed 42%-58%.

- 1924 Amendment – Creates Senate of 33 members. Counties have between one and three state house members. Apportionment required in 1925 and every ten years after. Passed 73%-27%.

By this point, the divide between rural and urban populations was already extreme. Under this plan, 1/3 of the population could elect a majority of the state senate and while Duval and 113,000 residents got three house districts, Lafayette and its 6,000 got one. Senate districts were supposed to be as equal in population “as practicable” – but the legislature drew a map that gave no such balance. Both chambers were malapportioned and would only get worse over the next three decades. South Florida growth would explode as the Everglades were drained and North Florida’s share of the state population would shrink as its share of the legislative districts remained intact.

The Pork Chop Gang

By the 1940s, the apportionment system was a major dividing line in Florida. The state was still single-party rule for Democrats; and the divide was urban vs rural. The rural lawmakers of North Florida wielded power in the legislature thanks to the malapportioned districts. These lawmakers, deeply conservative segregationists, would be eventually be called “the pork chop gang” by Tampa Tribune editor James Clendenin. The name, a reference to how they brought revenue home to their small districts, stuck.

The rapid growth in the south led to further clamoring for reform. A 1945 reapportionment session only occurred because Governor Caldwell demanded it, and passed little changes to the maps. Efforts by the legislature to amendment apportionment failed at the ballot box several times. All were efforts to keep the malapportioned plan in place while offering token changes to south Florida.

- 1942 Amendment – Add two new Senate districts. One made up of Broward County, the other from a combination of Gulf and Calhoun Counties. Failed 39%-61%.

- 1944 Amendment – Add three new Senate districts. One for Broward, one for Gulf/Calhoun, one for Osceola/Okeechobee. Moved formula for state house a bit. Failed 48%-52%.

- 1948 Amendment – Add two new Senate districts. One made up of Monroe County, the other made up of Gulf and Washington Counties. Failed 35%-65%.

- 1952 Amendment – Add one new Senate district, made up of Bay and Washington. Failed 30%-70%.

- 1952 Amendment – Add one new Senate district, made up of Monroe County. Failed 31%-69%.

By the 1950s, apportionment was one of the biggest issues in Florida political circles. Less than 20% of the population could elect a majority of both chambers and Florida ranked near the bottom when it came to state legislative malapportionment

The Pork Chop Gang Clings to Power

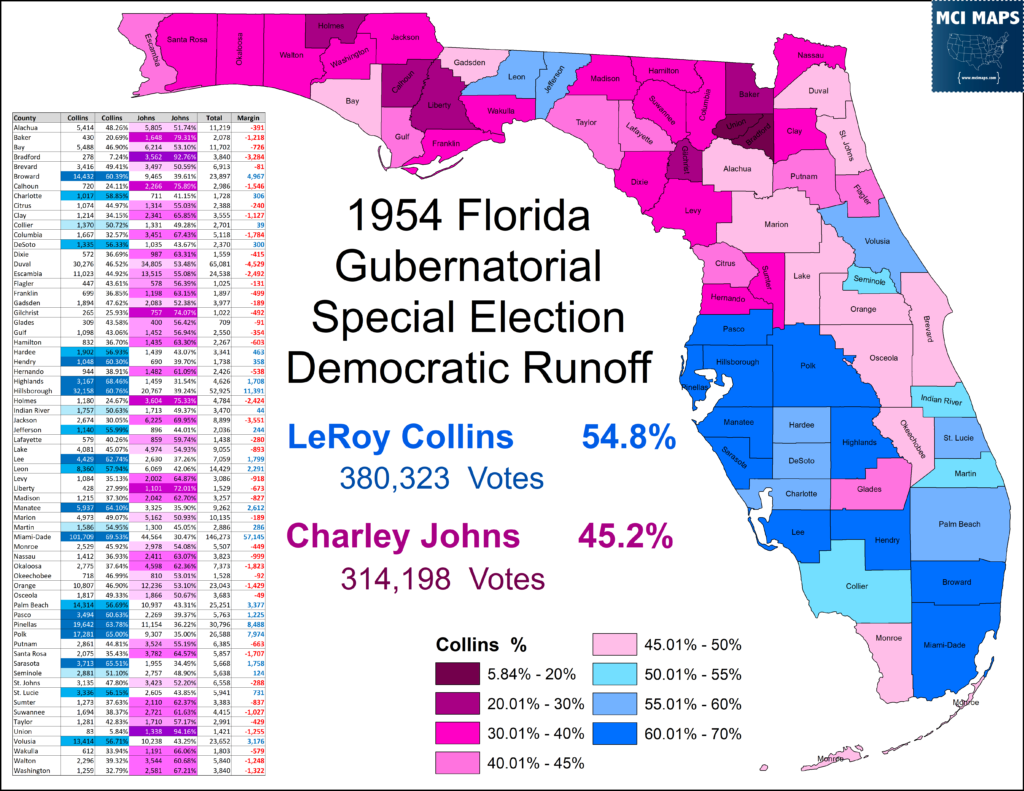

The Pork Chop Gang got a big enemy in 1954 when LeRoy Collins was elected Governor. Collins won a 1954 special election (triggered by Governor McCarty’s death) by defeating fellow Pork Chopper Charley Johns.

Collins campaigned as a reformer and against the malapportionment in the legislature. Once in office, he’d battle with the Pork Chop Gang over reapportionment.

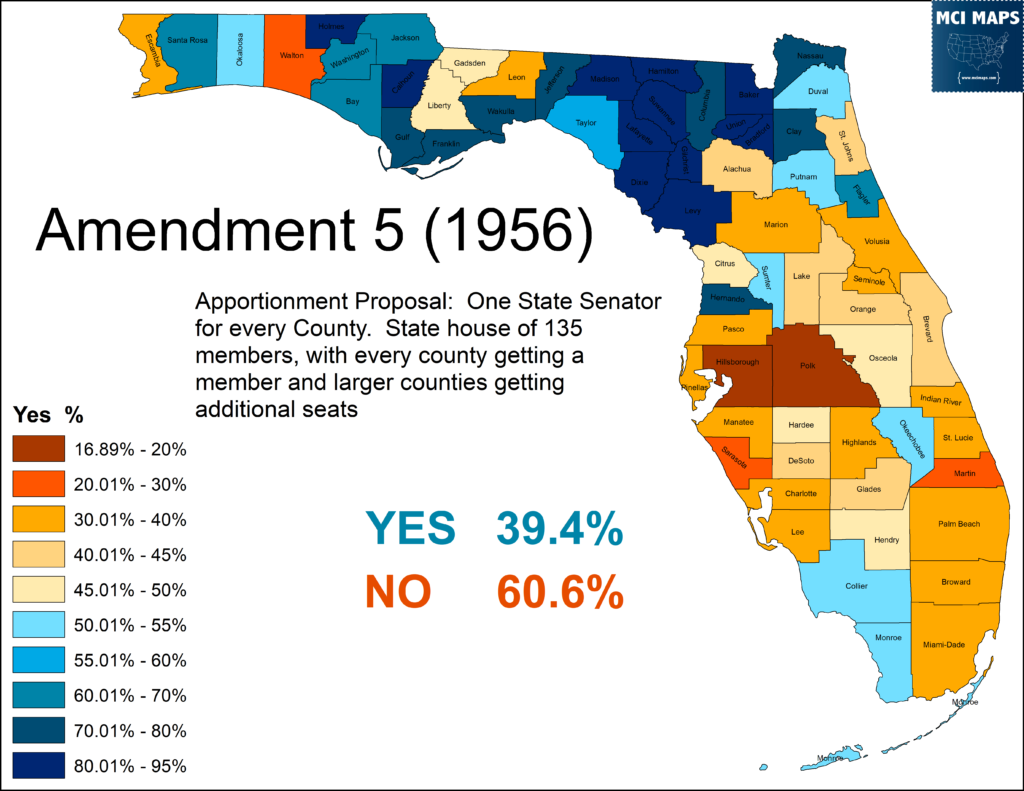

The 1955 apportionment session was dreaded by the Pork Chop Gang. The plan to delay with another referendum came in the spring. The proposal would give each county a state senator, with the county methodology changing – allowing for more representatives in the large counties. The proposal was an improvement for the house, but it was still weakened by the guarantee of a house seat for each county. Under the plan, 30% of the voters would be be needed to elect a state house (bad but better than sub-20). However, only 10% would be needed for the state senate. In addition, the the continued growth in the urban counties meant those percentages would only continue to fall. The measure failed.

The divide between the rural and urban counties continued to grow. Collins’ clashes with the Pork Chop gang were unable to yield a positive outcome, however. Efforts to make changes continued to fail. Another proposal was put before the voters in an emergency referendum in 1959; which likewise failed. Analysis showed the proposal would not fix the malapportionment issue; but several urban counties supported it for their own representation gains under the plan.

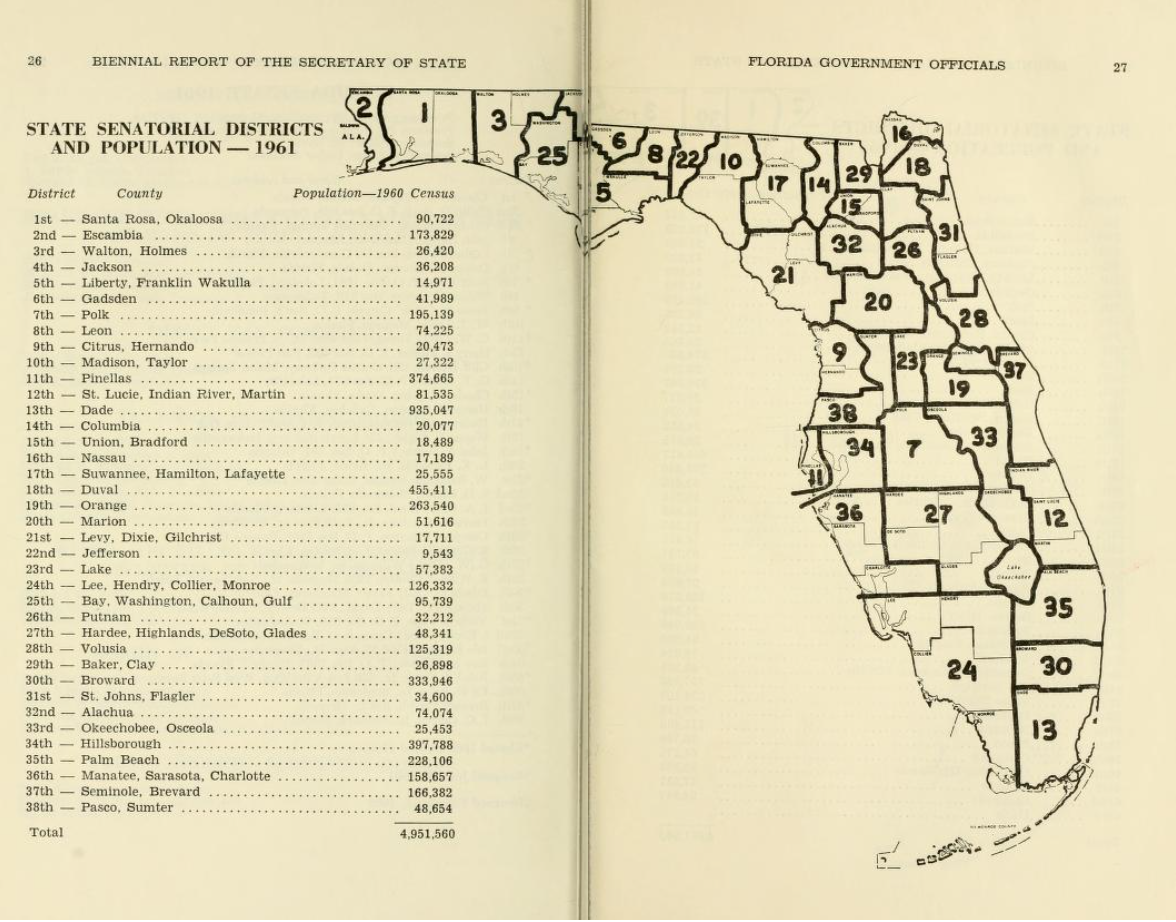

As the 1960s began, the State Senate map looked like this – with the largest district having 900,000 people and the smallest having less than 10,000.

Heading into the 1960s, apportionment only grew as a major dividing issue in the state. However, the stalemate would soon be broken with an intervention from the courts.

Fall of the Pork Chop Gang

As Florida grappled with its apportionment stalemate, the courts were beginning to get more involved in apportionment and redistricting. There was no choice for the courts at this point. Florida’s constitution gave little power to the state judiciary or the governor. By 1961, 12% of the state’s population could elect the Florida Senate, and 14% could elect the Florida House. Meanwhile, the Pork Chop Gang lived up to their name, ensuring their rural/small counties got outsized shares of revenue allocation. This situation began to finally collapse in 1962, with the Baker v Carr decision from the US Supreme Court. Things can get convoluted here, so lets lay out events in a timeline format.

- April 1962 – Baker v Carr – The US Supreme Court ruled that issues of apportionment and redistricting could be in the purview of the courts (was in relation to lawsuits over equal population of districts – decision gave clear indicator the courts would get involved in malapportionment cases).

- July 1962 – A 3-judge federal court invalidated the legislatures apportionment plan. Legislature met in special session and put a new plan before the voters. The amendment, which did not fix the malapportionment issue, was rejected by voters 45%-55%.

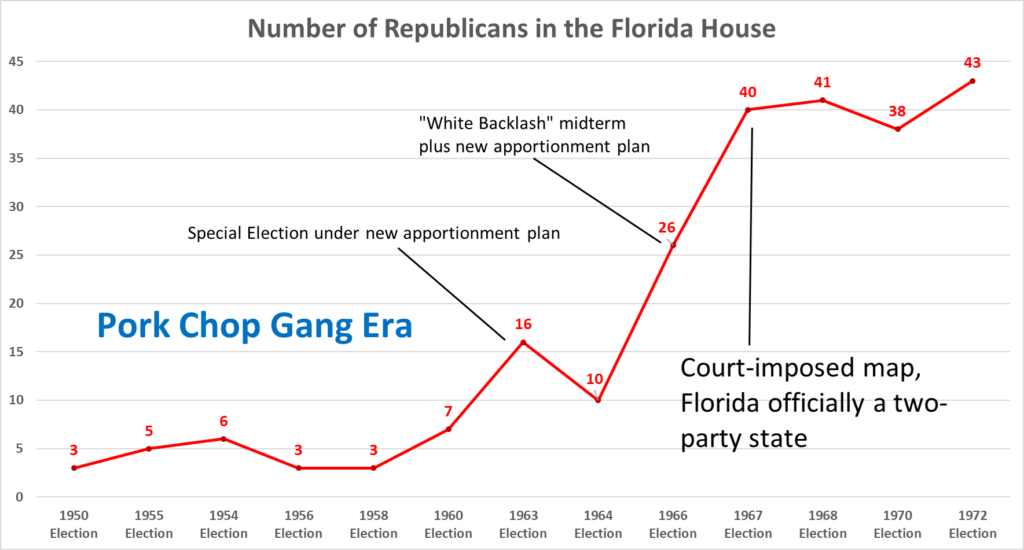

- February/March 1963 – With the 1962 midterm results thrown out by a court, a special election for the legislature under a new plan. While the Senate could still be elected by just 14%, the house now required 27% of the population to elect a majority. This was “better” but still malapportioned. The elections saw more urban members elected, but the plan would be struck down.

- June 1964 – Reynolds v Sims – Court set up the “one person, one vote” principle and ruled against geographic redistricting (vs population).

- June 1964 – Swann v Adams. US Supreme Court struck down the legislative plan for violating “one person, one vote.”

- November 1964 – Voters reject an amendment that reflected the legislative plan already tossed out by the court. Measure failed 35%-65%.

- June 1965 – Legislature passed another plan, ahead of a July deadline from the Court. Plan did represent a massive improvement. Majorities of both chambers now needed at least 40% to win control.

- February 1966 – Swann v Adams (2). US Supreme Court invalidated latest plan for not adhering to “one person, one vote.”

- March 1996 – Legislature passed another redistricting plan, this one means 47% of vote needed to win majority of both chambers.

- January 1967 – Swann v Adams (3). US Supreme Court strikes down the latest plan, invalidates the 1966 midterm legislative results. Court orders the lower court panel to pick a new plan themselves.

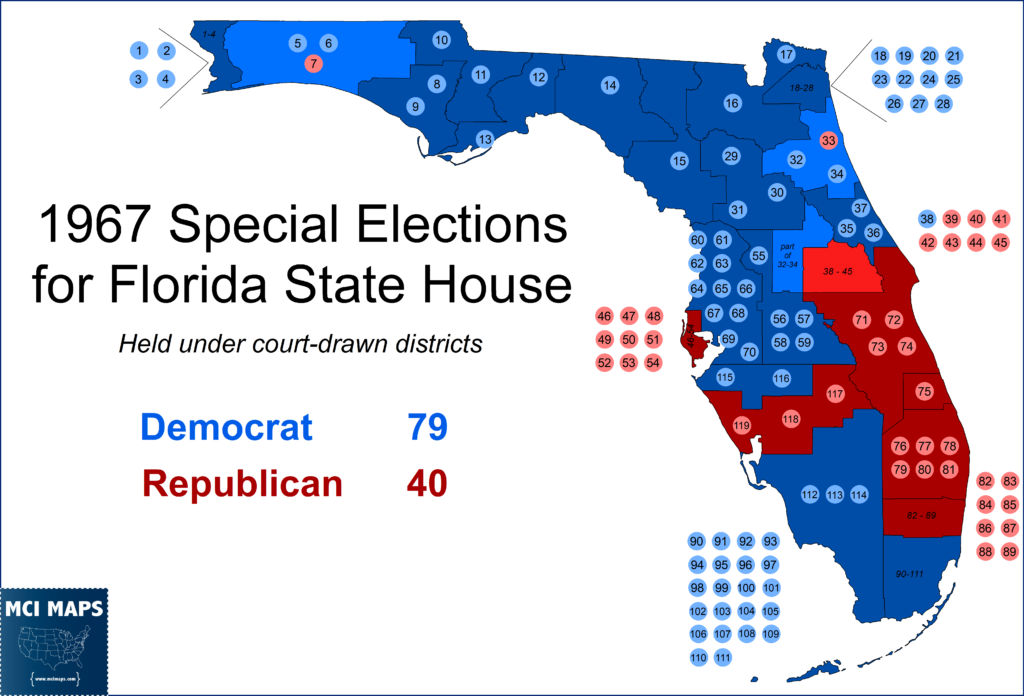

- February 1967 – District court announces its new plan, drawn by UF Political Science Professor Manning Dauer Special elections scheduled for late February and March.

The court-approved plan finally meant both chambers of the legislature needed 50% of the voters to elect a majority. Just 6 years ago, it only took 15%.

The court ruling set off a rushed campaign. The final map was decided in early February, with primaries held later that month and the general election at the end of March. Several remaining Pork Choppers were paired into the same districts and had to face off in Democratic primaries. The final results saw Democrats maintain a solid majority, but with a notable growth in the GOP caucus.

The results also codified Florida as a two-party state. GOP gains made in the 1966 midterms were improved upon just months later. While this growth is party thanks to the 1966 “White backlash” midterm (which saw Republican Claude Kirk win the 1966 FL Gubernatorial election) – the collapse of the North Florida Dixiecrat domination of the legislative plans also played a major role.

This election formally marked the end of pork chop rule and the beginning of modern Florida.

The 1968 Florida Constitution

While Florida’s apportionment battle was going on, efforts to make massive changes to the state’s constitution were already underway. Reform-minded lawmakers were able to get an amendment placed on the ballot in 1964 that allowed for the legislature to propose a new constitution. This measure narrowly passed, 51-49.

In 1965, the legislature created a Constitutional Revision Commission; which began its work in 1966. Any final product would need legislative approval – and its likely many Pork Choppers figured anything radical could be blocked. The court-ordered pork chop collapse was something these lawmakers did not see coming.

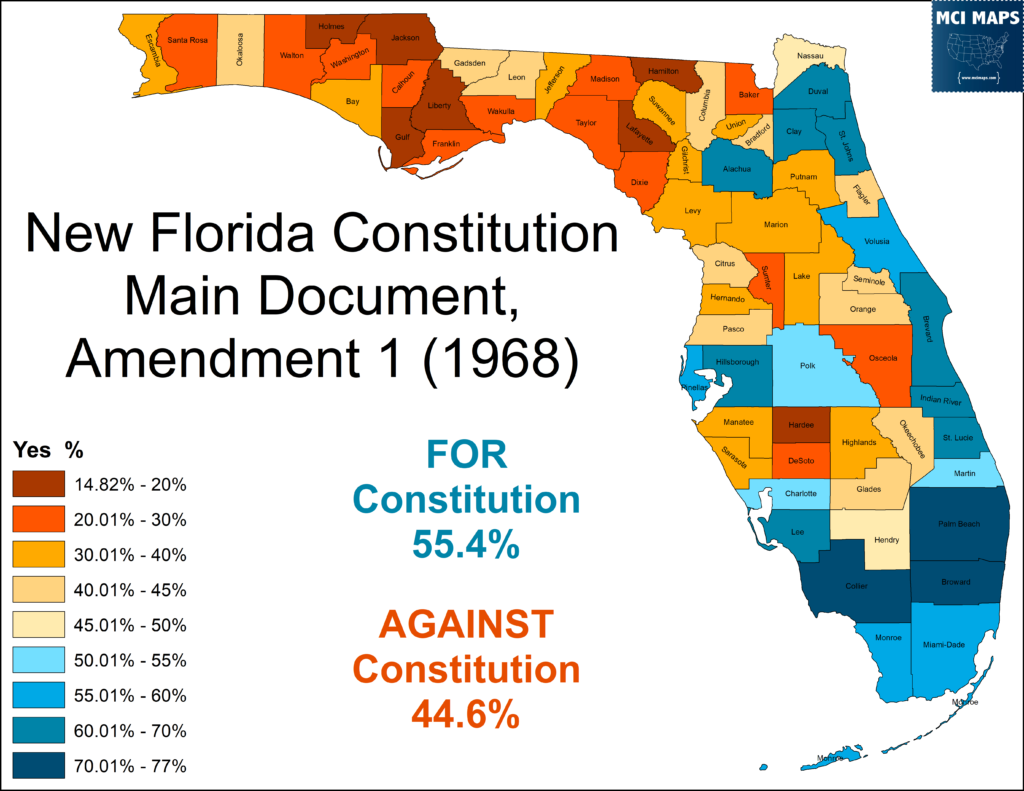

The CRC worked through 1966 on drafts, amendments, and held public hearings. Efforts to look into the CRC drafts were delayed by the 1967 court order for new districts and new elections. It wouldn’t be till 1968 that the newly-elected legislature could look over the CRC documents and come to an agreement on a new constitution. The document would be put before the voters on the 1968 ballot. The document formalized the equal population requirements for legislative districts and allowed for a range of 30-40 senators and 80-120 house members.

This constitution passed with the support of the larger urban counties. Many rural counties broke against the constitution due to its apportionment rules and its repealing of the racial segregation provisions of the 1885 document. Leon County notably voted against the measure because they worried the constitution’s new popular initiative process would lead to a ballot measure to move the capital out of Tallahassee.

Conclusion

Florida’s battles of malapportionment mimic what modern redistricting battles have shown; politicians in power will do whatever they can to hold onto their offices. Federal intervention finally broke the Florida Pork Chop Gang, but redistricting battles did not end there. Through the 1970s to 2000s, both Democrats and Republicans worked to gerrymander districts to protect their own interests. In the next article, we will look at at the gerrymandering of the late 20th century and heading into the 1990s.