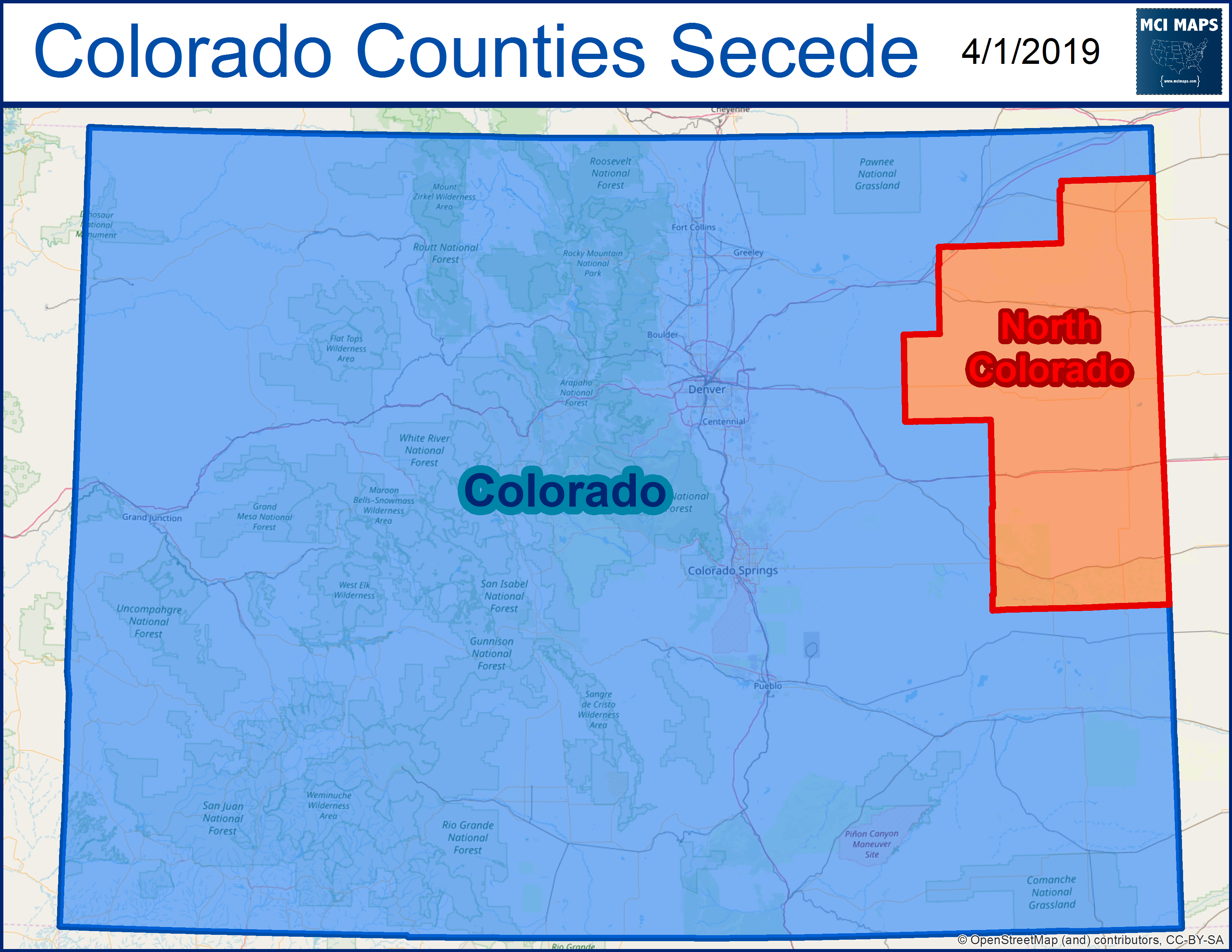

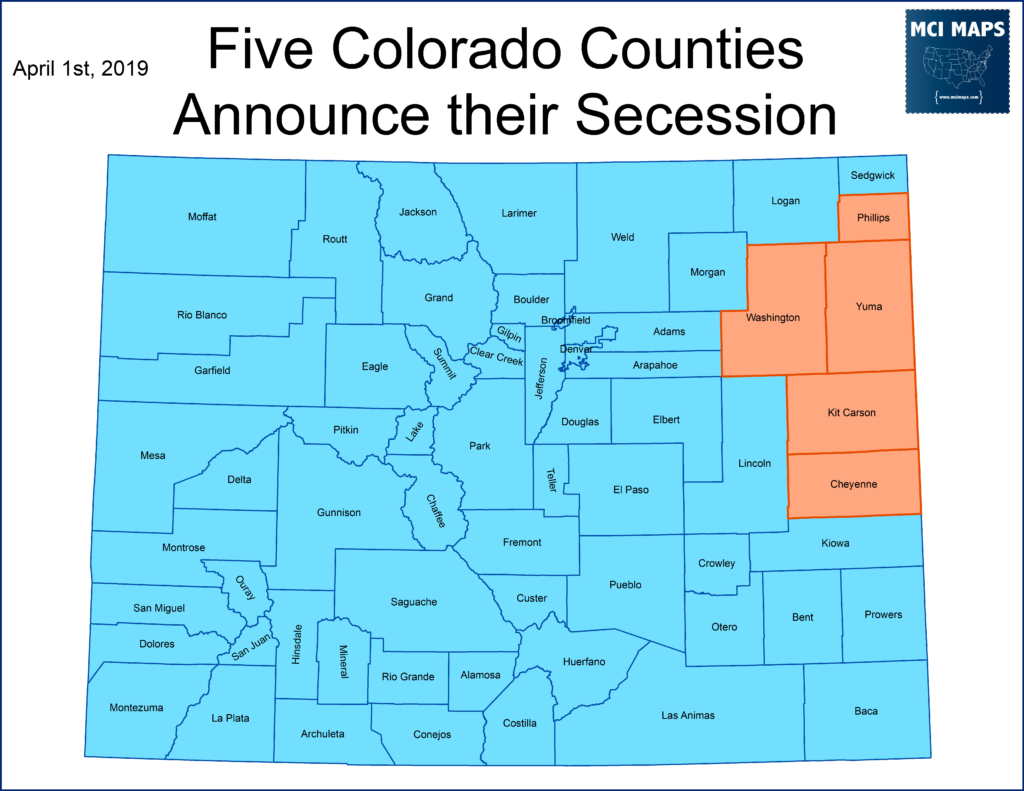

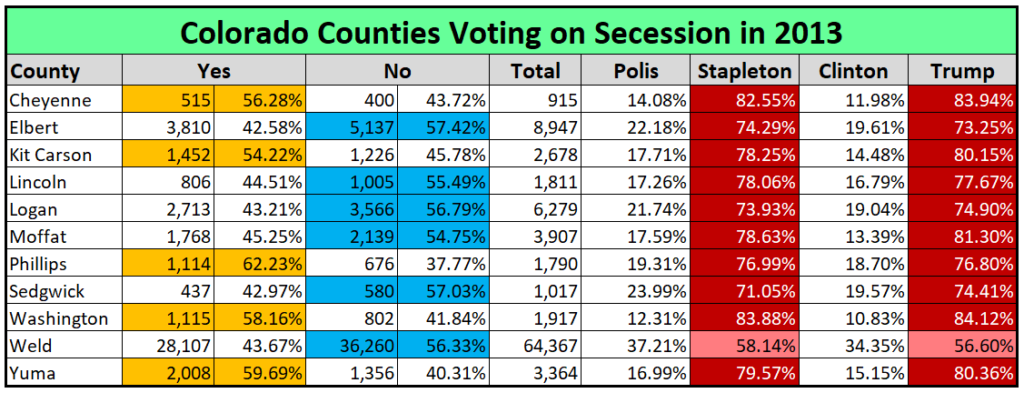

In 2013, eleven rural Colorado counties held referendums on seceding and forming a 51st State – “North Colorado.” The referendums were, of course, non-binding and really served to send a message to the state government. The conservative counties were unhappy with liberal legislation coming out of a state that has been ticking more to the left in recent years. In the end, five counties voted to leave, while six voted to remain.

Afterward, nothing really changed. The State Senate flipped to the GOP in 2014 and liberal legislation halted. However, with the 2018 elections ushering in solid Democratic majorities and a liberal governor, the rural counties began agitating again. In March, State Senator Vicki Marble said secession may be needed for the rural counties. She hails from Weld county, which didn’t support secession then and whose local officials say they don’t support now. However, the next several weeks saw the issue continue to come up as the legislature passed new bills further regulating the oil and gas industry in the state.

Then, over the weekend, rumblings emerged that several small counties might make a proclamation that they wanted to leave Colorado. It came to fruition Monday morning, as the original five counties that voted to secede in 2013 announced they were seeking to leave the state.

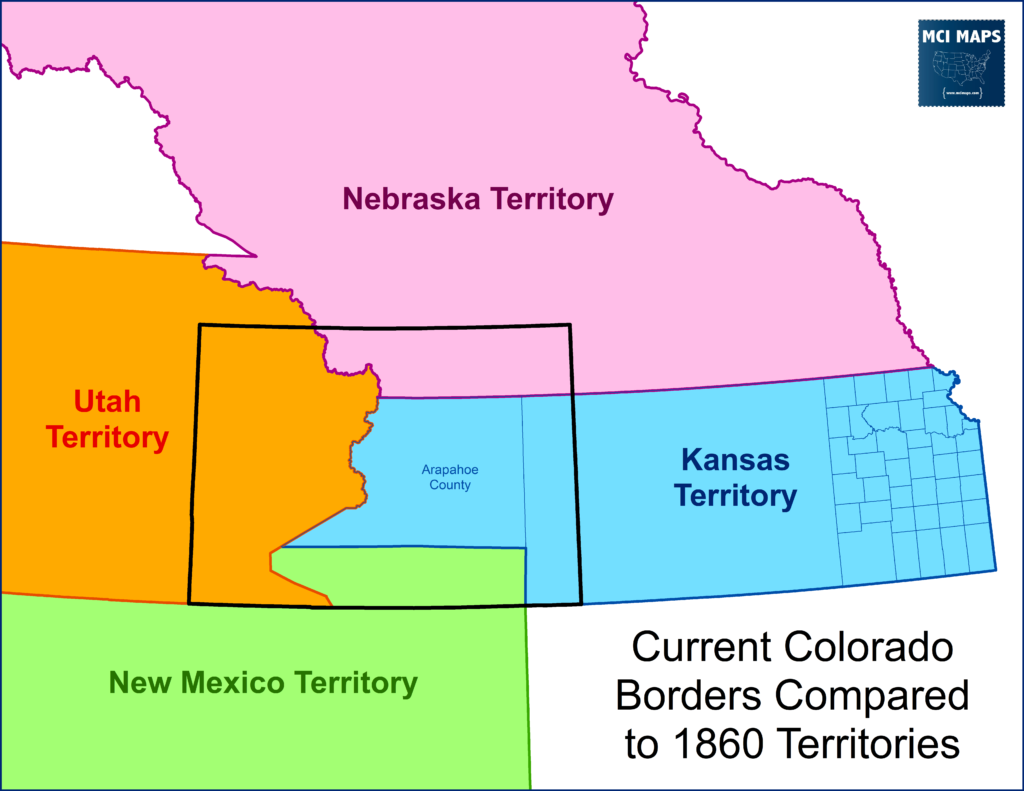

This secession push is ironic considering Colorado’s own history. The state actually was a break off from Kansas. Western Kansas gold miners even declared their own territory.

Lets look at the crazy history of Colorado’s statehood push.

History of Colorado

Seceding from Kansas

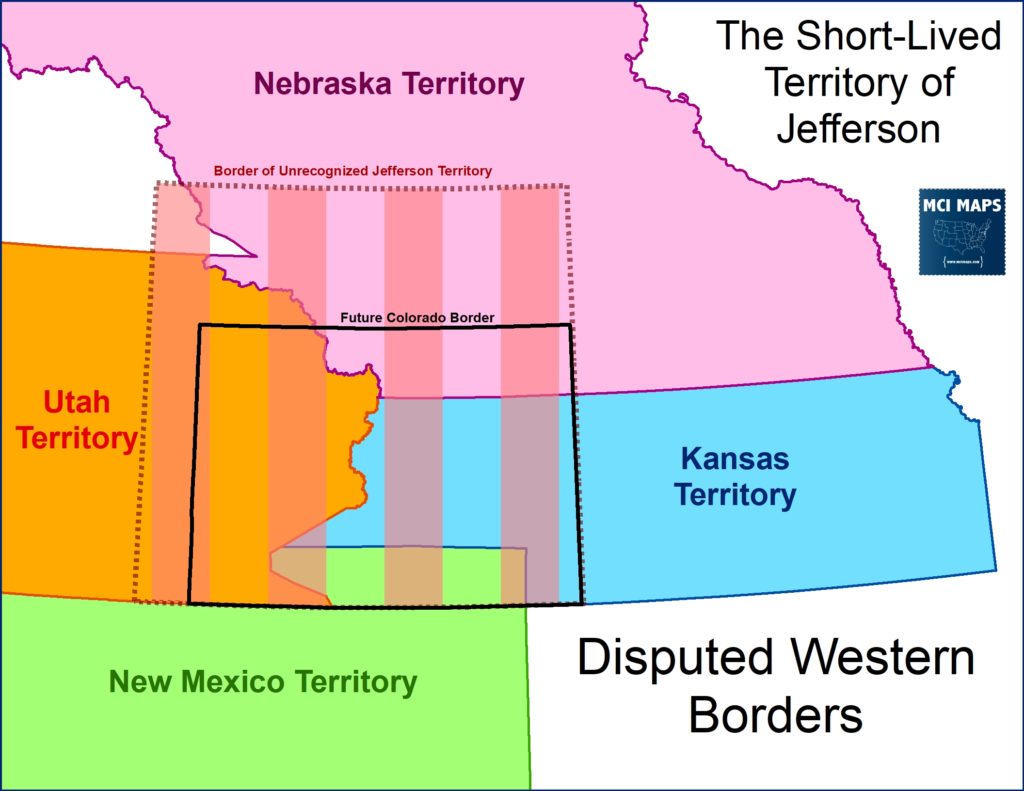

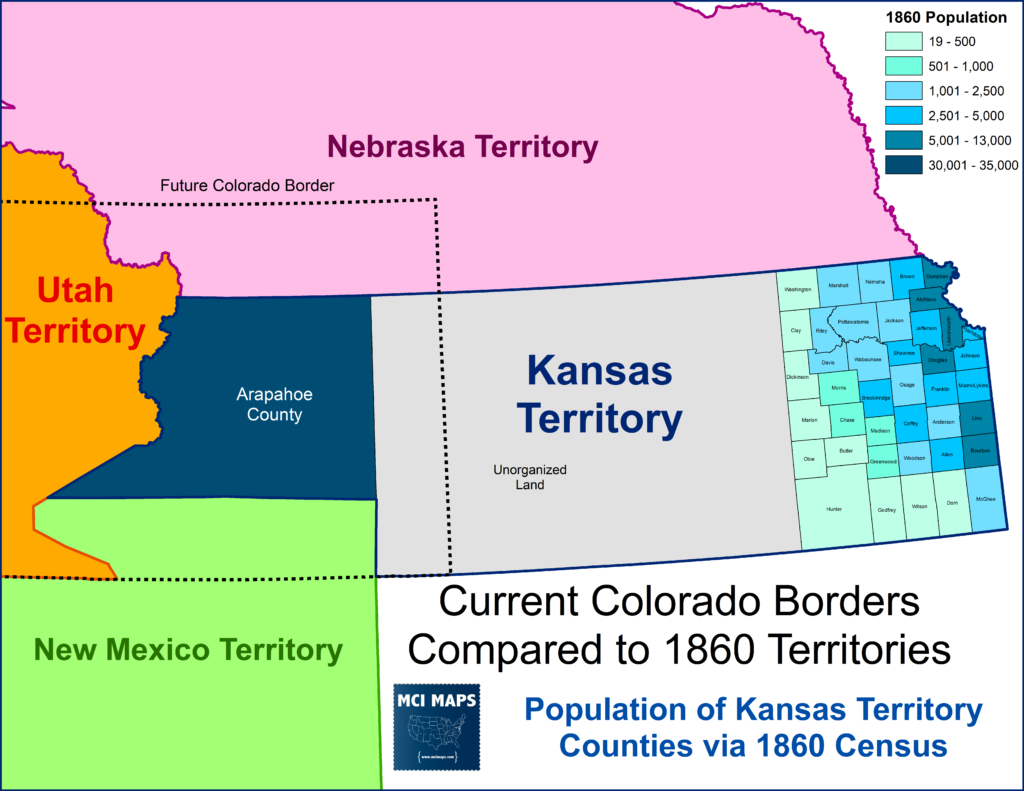

Much of what is now Colorodo was made up of several territories, namely those of Kansas, Nebraska, and Utah.

The whole region was very low in population. Much of the area that became populated fell within the Kansas County of Arapahoe. In 1858, gold was discovered in the region, and a gold rush, not unlike the one in California, began. Prospectors rushed to the region and local governments began to form. Kansas further divided Arapahoe into six counties and appointed commissioners, but the positions were never paid for and the people never took their posts. The people of the region continued to govern themselves and formed their own governments, effectively ignoring the fact they were under the Kansas territory jurisdiction. Between them and the main counties of Kansas was unorganized land; creating a real divide between the east and west territory.

In 1859, the residents of the gold fields voted to form their own government; the Jefferson Territory. The land claimed was far larger than the gold fields.

Goals of the territory depend on who you ask. Many of the elected officials for the territory sought to become their own state while others wished to be united with Kansas. However, many officials in Kansas did not desire to hold on the western portion of the territory. Power in Kansas had long been concentrated in the eastern border and the growing western gold fields threatened to upset that.

By the time of the 1860 census, Arapahoe County had a larger population than any other county in Kansas. The local officials even argued this 35,000 figure was under-counting gold miners out prospecting; and that the actual total was closer to 60,000. The county was already acting like it was part of this “Territory of Jefferson” – but many Kansas officials feared that if it its residents got involved in Kansas politics, then political power would instantly tip west.

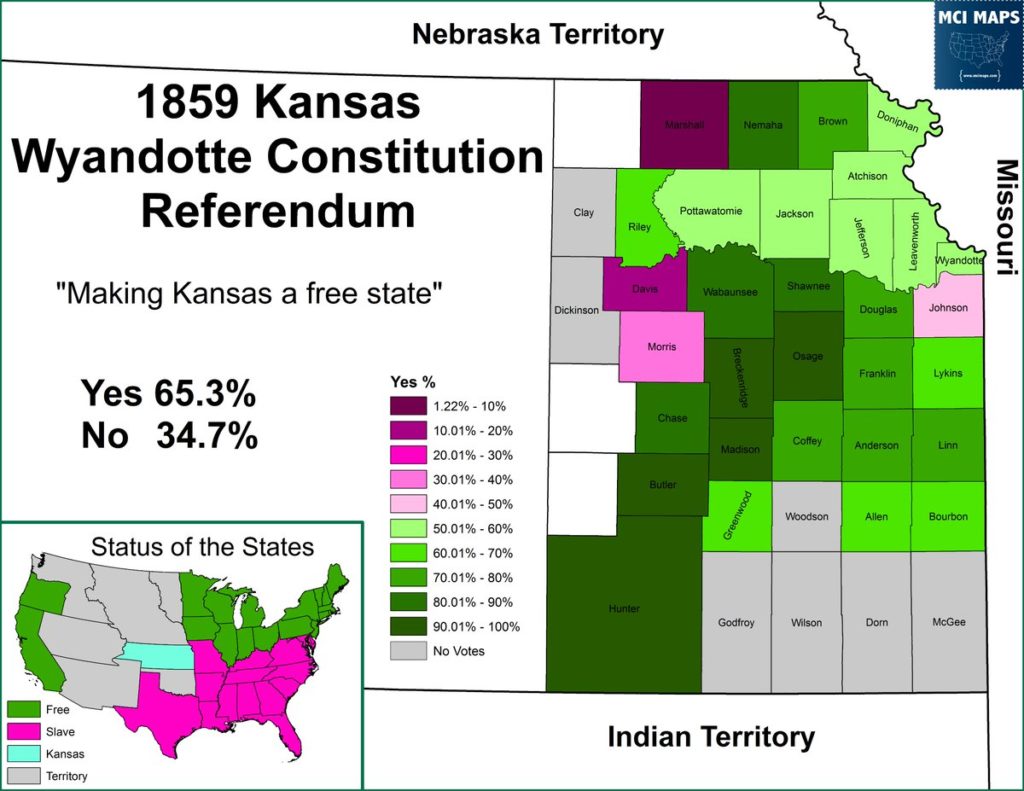

Kansas had voted in 1859 (which the west did not participate in) to approve a free-state constitution and statehood was a major issue heading into the upcoming Civil War.

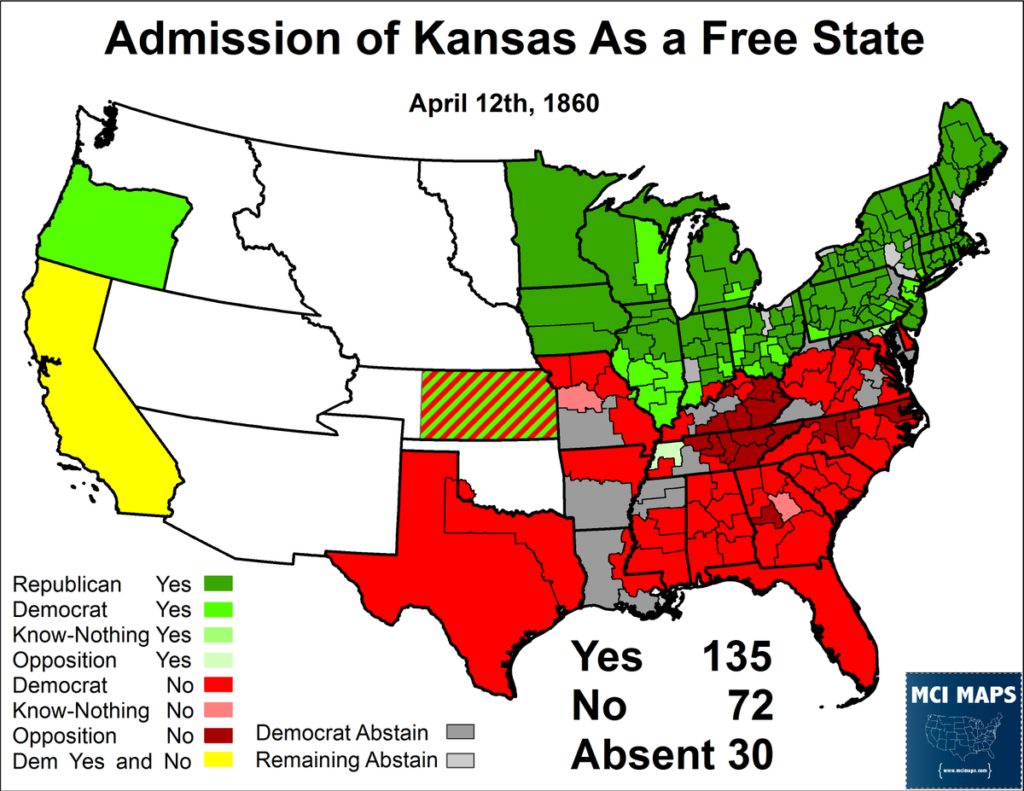

In 1860, with Lincoln’s election and the Civil War just months away, Kansas was admitted to the union as a free state. Congress cut off Kansas’ western portion (at the same line the Jefferson Territory claimed) and left the region unorganized. The government never recognized the Jefferson Territory, but acknowledged a government was needed for the gold fields.

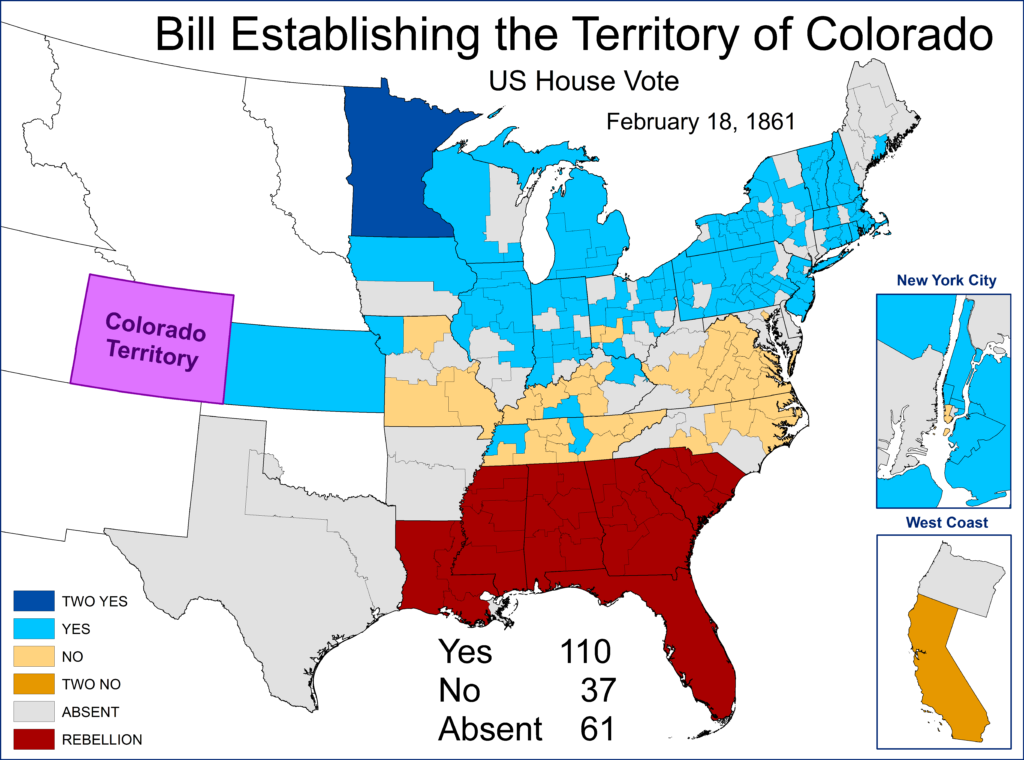

A few months later, in early 1861, Congress approved a bill establishing the Territory of Colorado. It was smaller than the Jefferson Territory but shared its southern and eastern borders. Jefferson officials welcomed the move. The vote easily passed but saw opposition from border states. Already several southern states were in open rebellion and hence did not have members in congress.

Colorado went through a long history to achieve statehood from this point. As the civil war raged (including efforts from a Kansas militia to take Colorado’s gold fields, which failed) the territory aimed for statehood. The timeline of events is as follows

- March 1864 – Congress passes a law to admit Colorado as a state, pending a constitution and voter approval (hoping for extra GOP electoral votes that fall)

- October 1864 – Colorado voters REJECT the constitution drafted

- September 1865 – Colorado voters APPROVE a new constitution

- Andrew Johnson, now President, refused to admit Colorado (knowing they will likely send GOP Senators)

- May 1866 – Congress passes a law approving Colorado statehood, but Johnson vetoes

- January 1867 – Congress passes another Colorado statehood bill, but Johnson vetoes

- Colorado statehood falls as a priority once Grant elected and reconstruction (under harsher rules) begins

- 1873 – Grant calls for Colorado statehood

- March 1875 – Congress approves Colorado statehood bill (pending new constitution and vote by the people)

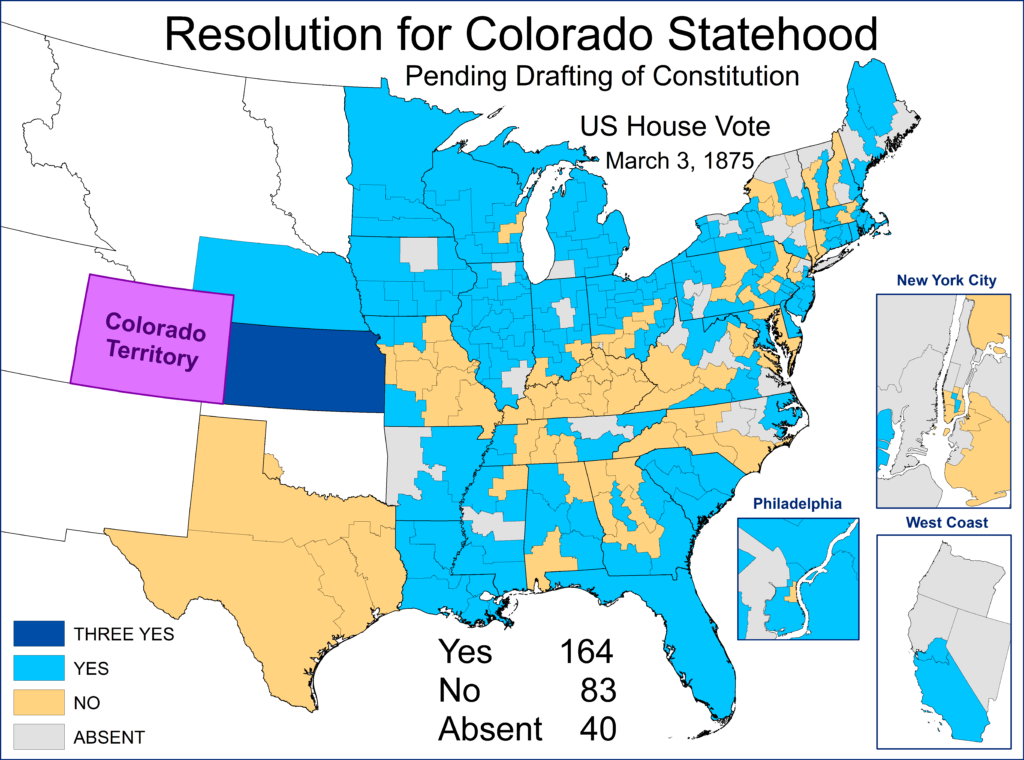

The 1875 vote was critical. The GOP-controlled House lost its majority in 1874, but the new congress would not be seated till March. Just before this transfer of power, the congress voted on Colorado statehood. It was largely opposed by Democrats who feared another GOP state. However, the territory had elected a Democrat for Delegate in 1874, giving some party members less concern. The measure narrowly passed the two-thirds rule needed at the time (this happened at the end of the last congress). IF Democrats had remained united, it would have failed to get the two-thirds needed.

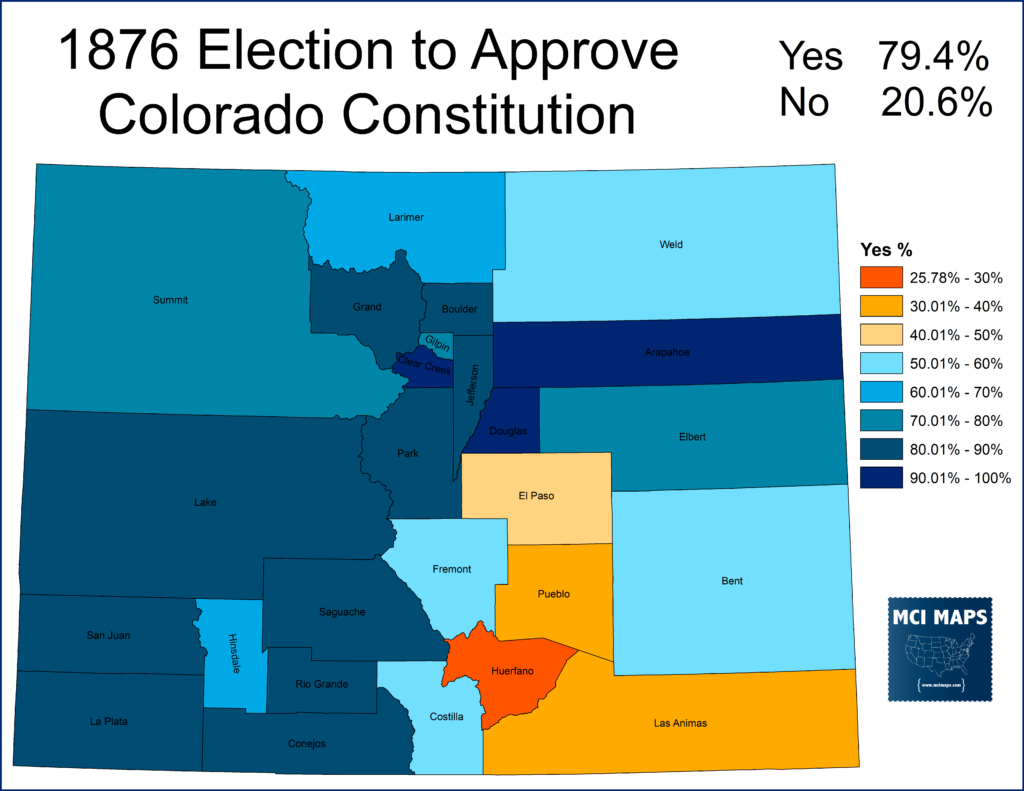

In July of 1876, Colorado voters approved a constitution and joined the union. As a result, they would be able to participate in the 1876 election.

Colorado’s role in the election would be pivotal, but often forgotten.

Swing State from the Start

Colorado was considered a lean-GOP state but Democrats did have hope they could win it. The infamous 1876 election saw Democrat Samuel Tilden beat Rutherford B Hayes in the popular vote, but lose the electoral college. The election was so close and controversial that a commission had to be formed to figure out the electoral votes for Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina. When the commission voted to award all 3 states to Hayes, he won the electoral college 185-184.

What people forget is that had Colorado, which gave its votes to Hayes, not been a state (which was only possible because a few democrats backed the 1875 House bill) – Tilden would have won.

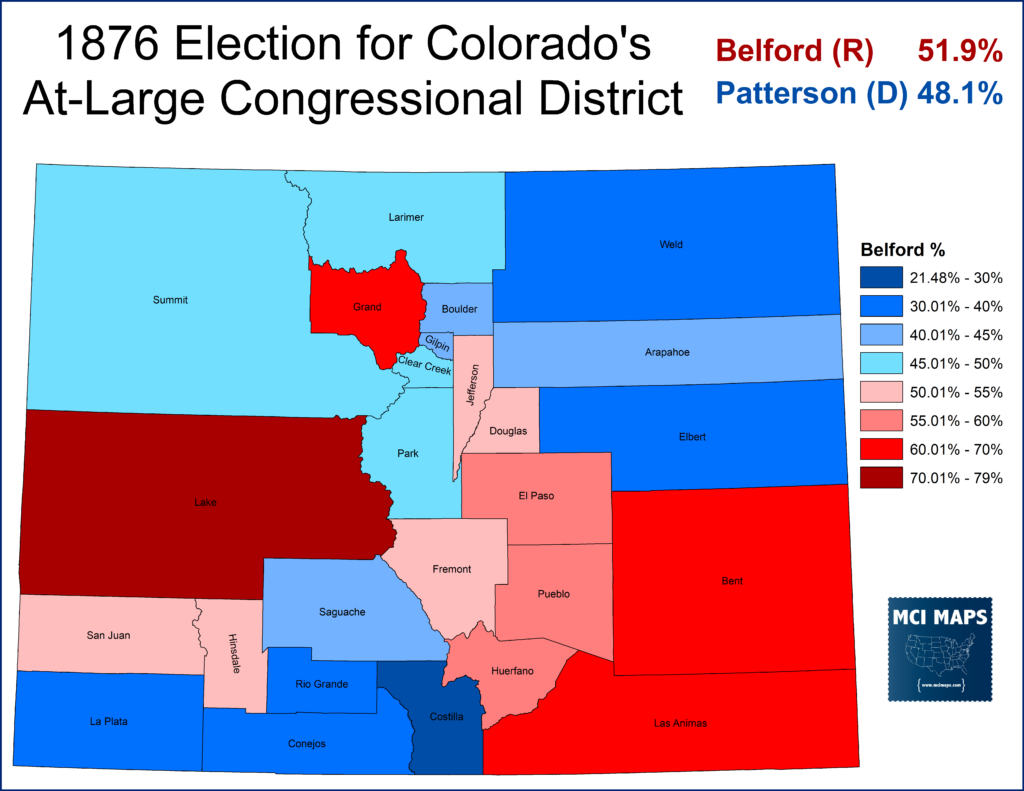

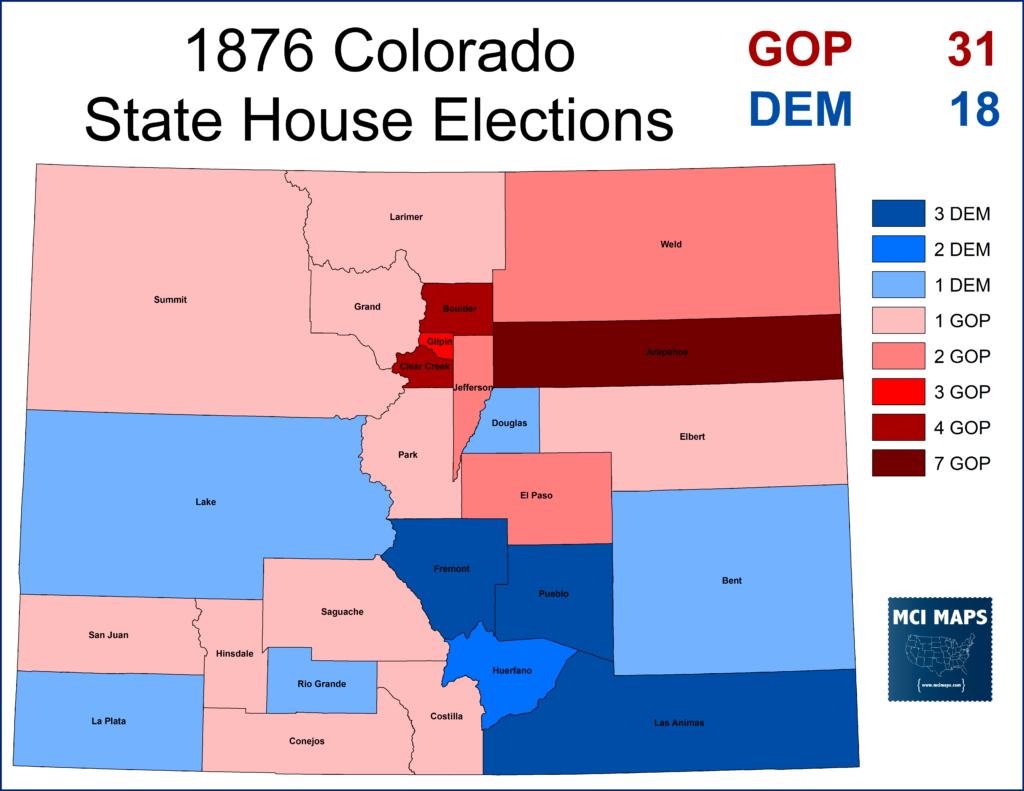

Colorado had a series of close elections in 1876. It narrowly voted GOP for Congress and Governor.

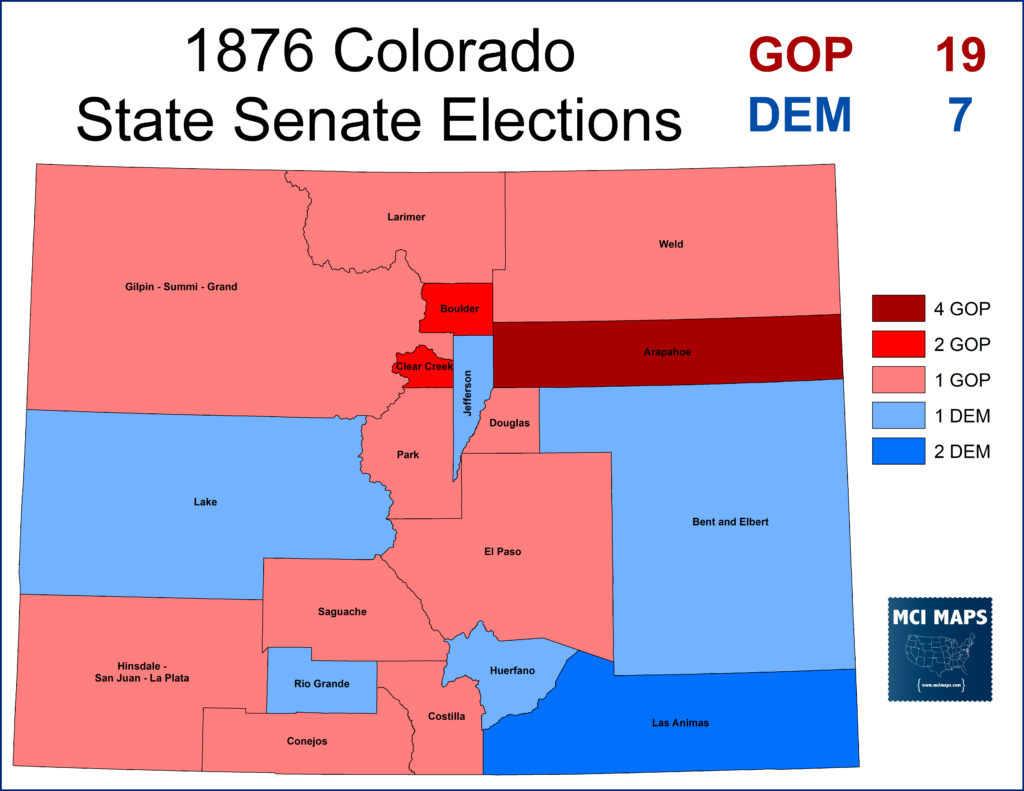

However, it easily voted for a GOP legislature.

These legislative elections were important. In 1876 Colorado had its electors chosen by the legislature, and not the result of a popular vote. This was a common practice in the early states of the nation, but was no longer used by this point. This was the only time Colorado would use this method.

Modern Colorado

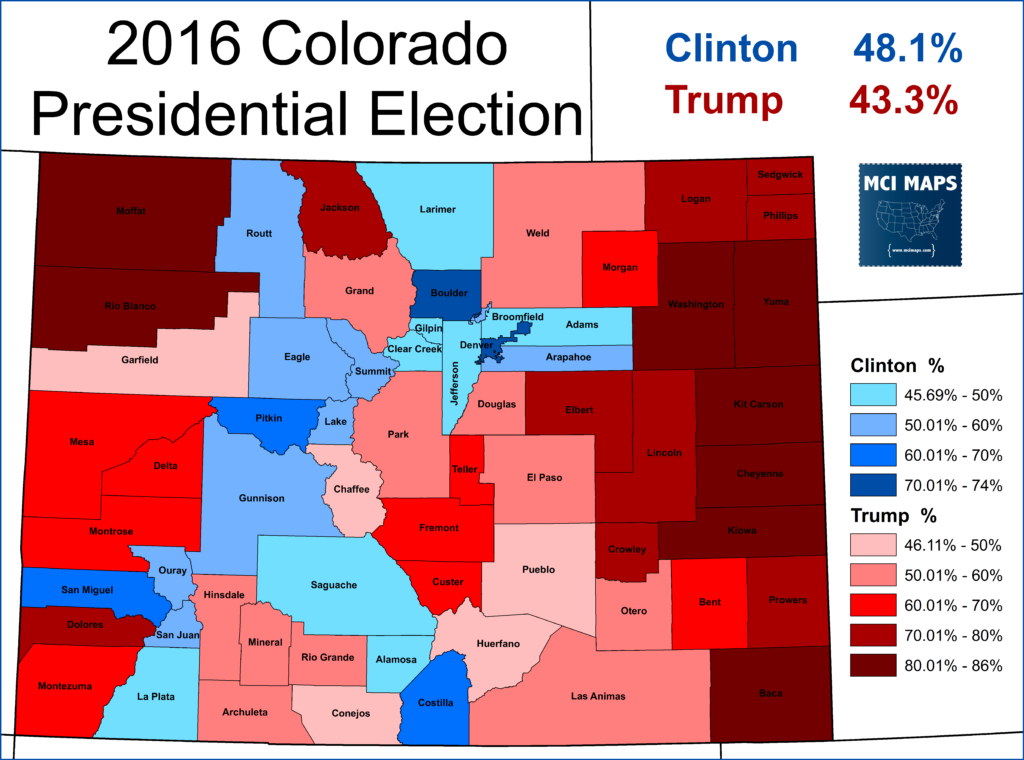

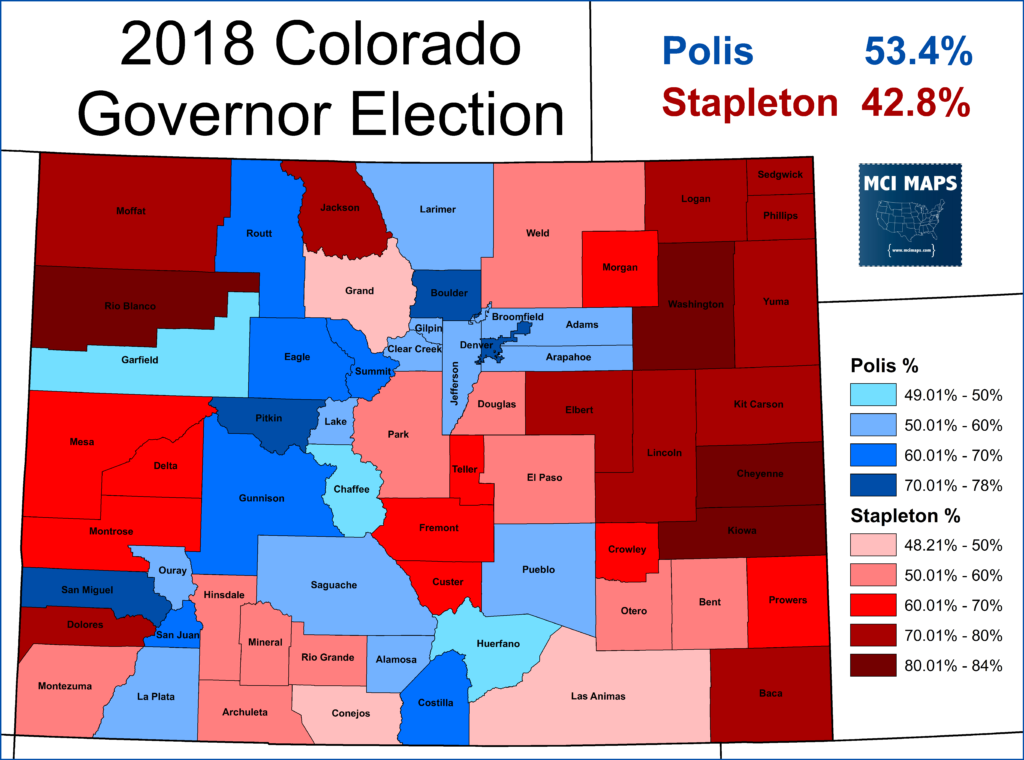

For much of the modern political era, Colorado leaned to the right of the nation. However, it has become much more democratic in the last few election cycles. Growing non-white and a growing higher-educated population (both groups trending democratic) have resulted in Colorado moving into Lean Democratic columns. The state has elected Democrats for Governor four times in a row and Democrat for President the last three. Republican Senator Cory Gardner is considered the most vulnerable GOP Senator up in 2020.

In 2016, Colorado backed Clinton by 5 points. In 2018, it voted for Jared Polis for Governor by 10.

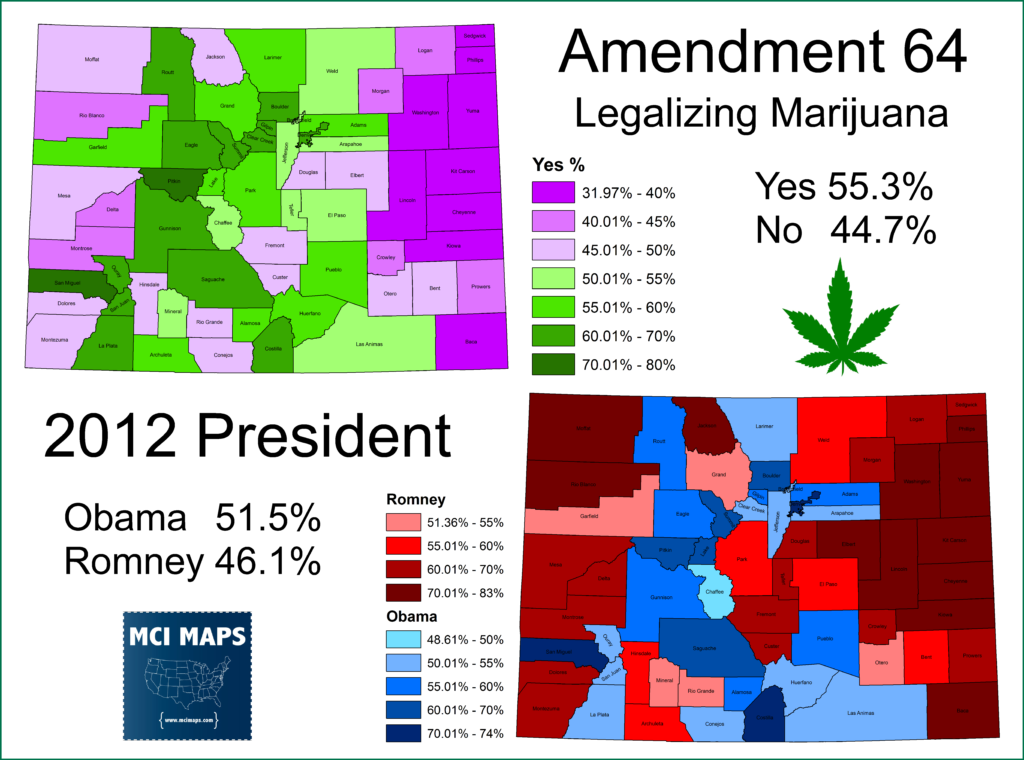

Polis’ also made him the first openly gay man elected Governor in the nation. Democrats also control all cabinet seats and the legislature – a level of party control unseen in Colorado in recent time. The state also voted to legalize marijuana in 2012.

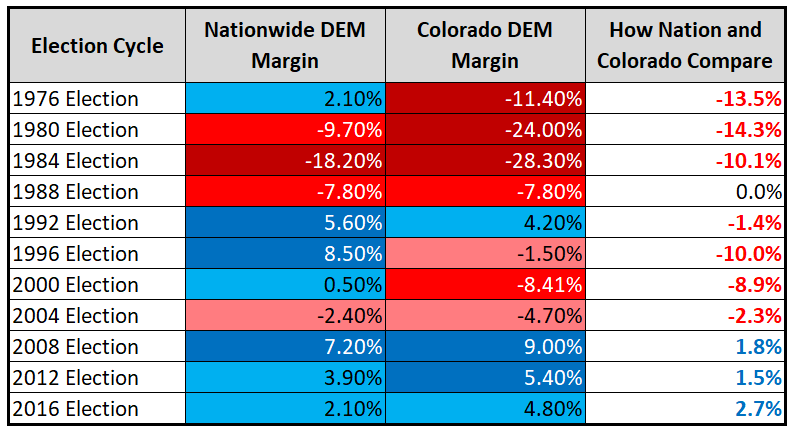

Since 1976, Colorado has moved to the left of the nation. Its still in a mild swingish column, but overall its trending blue. This table below compares how Colorado votes for President compared with the nation.

However, while the state grows bluer, the rural counties remain solidly GOP. Of the 2013 counties to hold secession referendums, all but Weld are over 70% GOP.

What has clearly happened is the rural counties of Colorado see their state government moving further to the left and their low population gives them little influence to stop it. The question is, what happens next? Congressional and state approval is needed for any dividing of a state. Colorado democrats should welcome the move, as it removes a small but very red group of voters from their elections. Of course, the counties are too small and rural to survive as a state on their own. They share borders with Kansas and Nebraska and could try to join either.

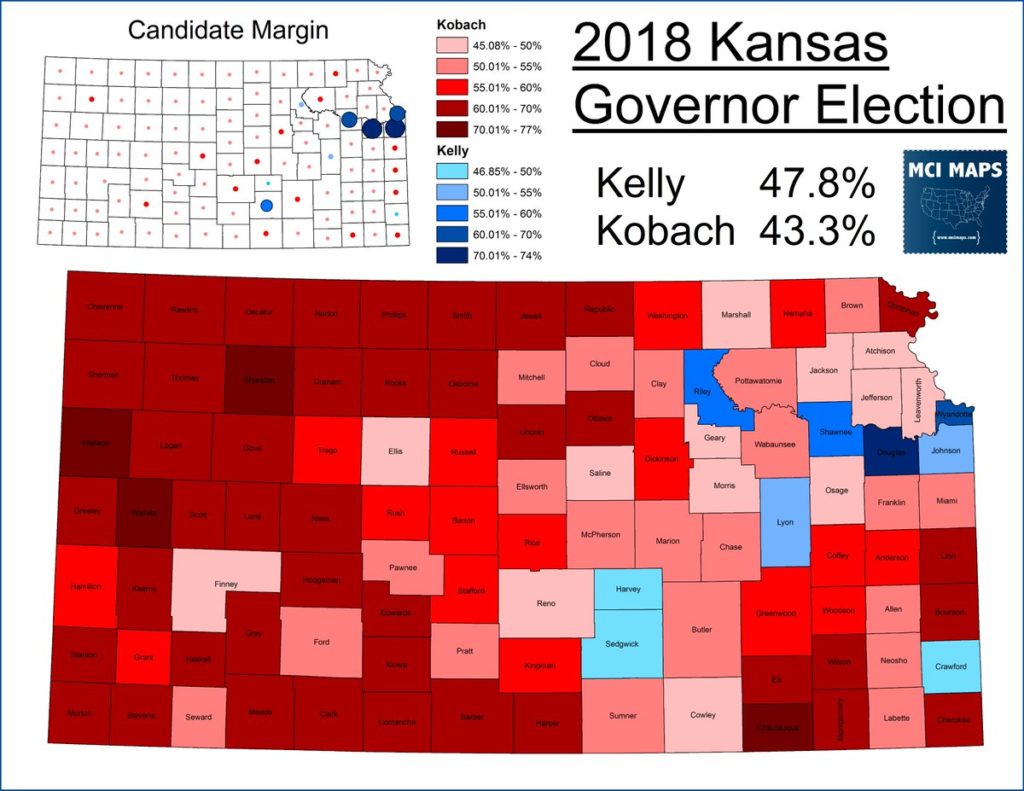

Rejoining Kansas would have some historic poetry to it, but considering Kansas elected a Democrat for Governor last cycle (who probably doesn’t want these GOP voters), I don’t think its very likely.

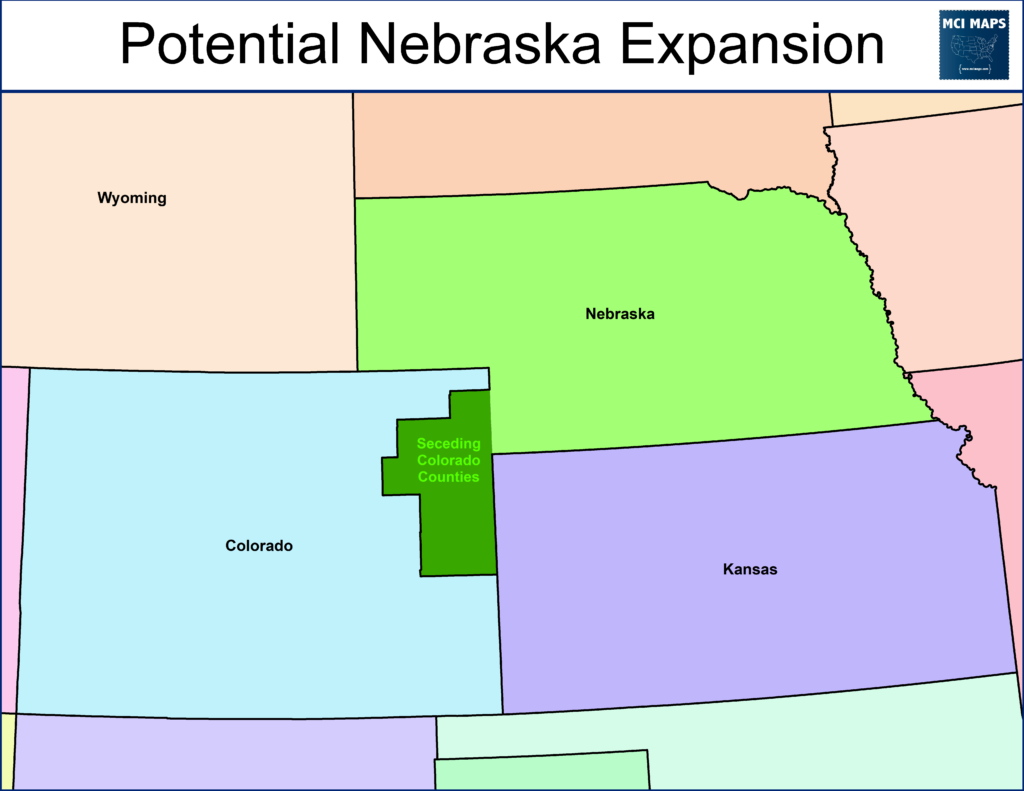

Nebraska then becomes the best option, as its already solidly GOP. Granted the map would look a little weird.

We will have to wait and see what happens. In the meantime, while its “not recognized” – the maps of Colorado may have to start looking like this…..

You can read the resolution passed by the five counties here.