October 31st, 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther nailing the 95 These to the the Catholic Church door in his town, beginning what we now call the reformation; the great split of the Catholic Church in Europe. Ok, actually the whole nailing to the door thing has been dramatized a bit, but the point is this is the date that is used to mark the beginning of the reformation.

The story of the reformation’s origins, timeline and effects is long and complex and not remotely what we are going to cover here because I do not consider myself a strong enough authority on the complex details. Rather I am a devout Lutheran with an obsession for maps and I can give us a geographic look at the effects the reformation have had on Christianity in America. I pulled from the Association of Religious Data Archives, who do a “census” every 10 years of adherents to faith in America. This data is skewed much more to those who actively practice their faith, and less focus is on “cultural” believers. This naturally reduced the totals compared to what polling might tell us.

Over 70% of Americans these days consider themselves Christian. That Christian bloc is heavily geared toward Protestantism but Catholicism also has a strong presence. Mormon’s (who largely do not consider themselves Protestant) make up a small share of Christianity but are heavily clustered in Utah and Idaho.

The map shows us not just the states dominated by Protestantism or Catholicism, but also the regional splits within states. Southern Louisiana is famous for its French Catholic history. Miami, Florida and southern Texas are dominated by Catholic Hispanics. The growing Hispanic population across the southwest has led to a growing Catholic presence in the region. New England is largely Catholic; a well known historical fact, and the South is overwhelmingly protestant.

Catholicism in America is largely united. Protestantism, however, can be sliced and diced many different ways. The main divide is between “Mainline” and “Evangelical” Protestantism. Their are many subtle distinctions but the main divide is over ideology. Mainline protestants are more moderate while Evangelical churches are more conservative. We see this in exit polls on voting all the time, where Evangelicals are overwhelmingly Republican while Mainlines are more split.

Mainline protestants are found much more in the North and Midwest while Evangelicals dominate the south and west. This is simply the breakdown within Protestantism however, so many of the western and New England states still have fair more Catholics. Mainline protestants used to be the majority but now are far behind Evangelicals. Part of this trend is not just growing conservatism in protestants but more and more protestants leaving for “unaffiliated” or non-denominational groups. The third group that makes up Protestantism is historically African-American church groups. These churches are separated from the others because of their long cultural and historic significance, especially in civil rights pushes.

Black Protestant churches are heavily clustered in American’s black-belt, the areas where slave populations where highest before the Civil War.

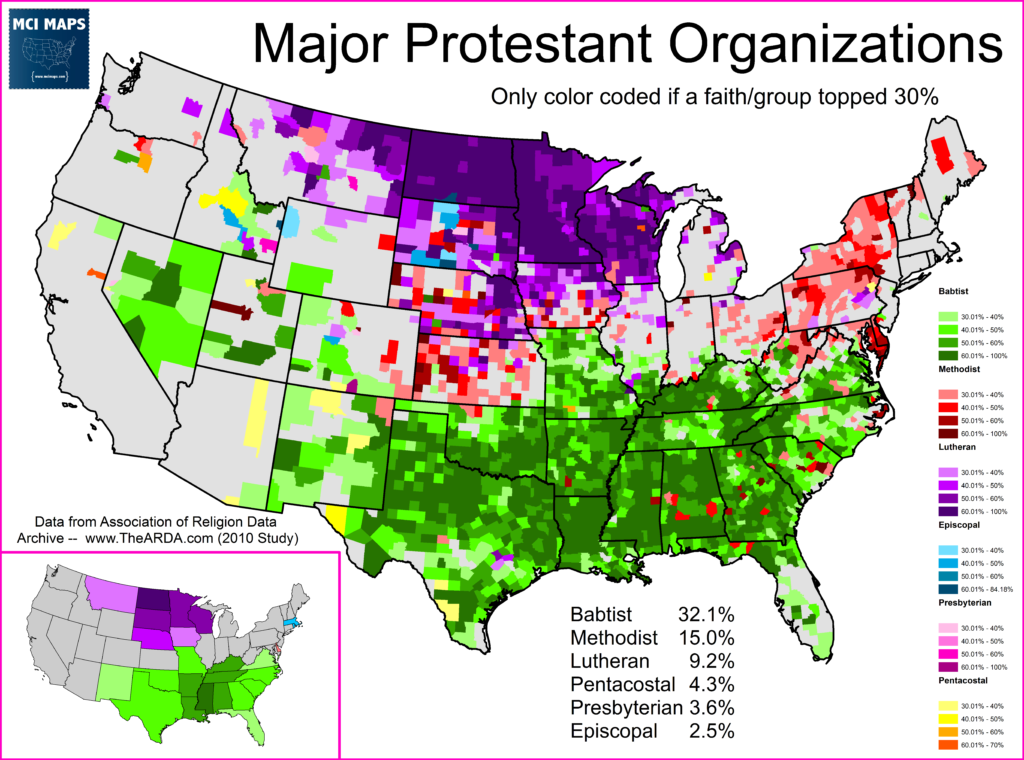

Protestantism is further divided by the different religious associations within in. Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans (the original reforms, you’re welcome), Presbyterians, and many many more groups make up “protestant faith”. In addition, the “non-denominational” version of Protestantism has been growing with the rise of mega churches faith services that do not identify with a specific protestant group. There are still areas where the main protestant groups still dominate. The map below shows where each group has the most followers, with anything less than 30% being voided.

The map tells us a few things. We see where different protestant faiths dominate geographically. However, we also see alot of grey zones — areas where non-denomination leads the pack or where the split between the different religious groups occurs between so many different organizations that its impossible to say any single group really leads. I saw several counties where the largest protestant faith group has 15% of the counties protestant adherents because the population was split so many ways.

Lutheranism in America

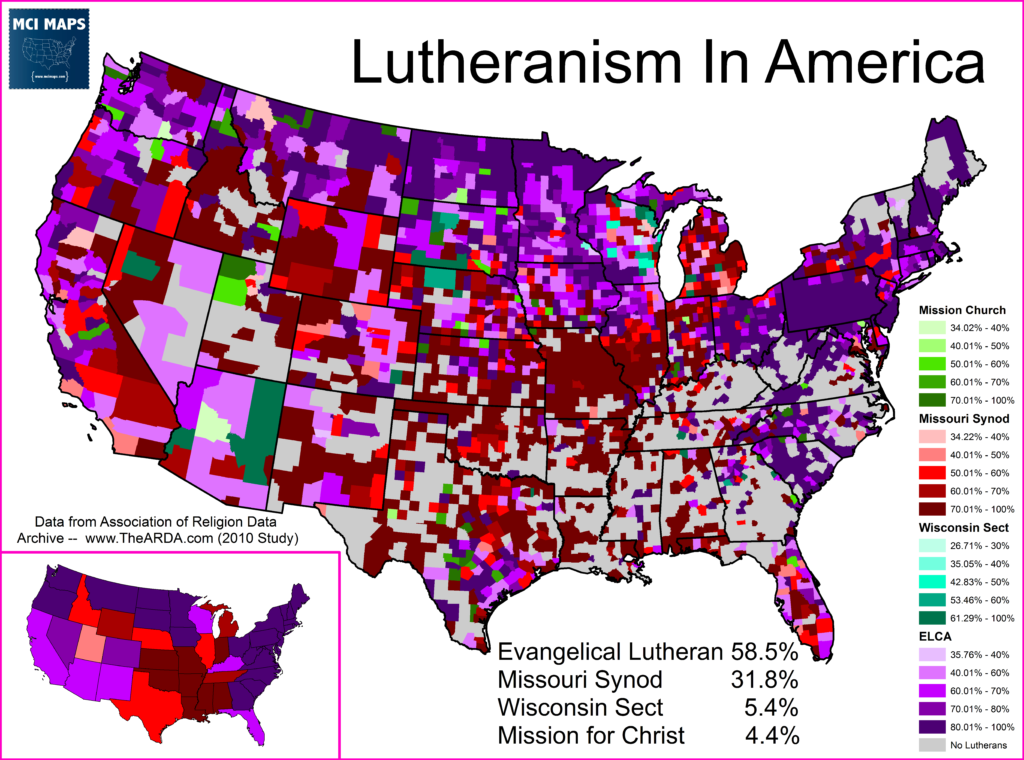

Of course I had to look at the current state of Lutheranism in America. The organization named after Martin Luther (though its not what he wanted) may have been one of the first break-offs from Catholicism but it does not dominate protestant faiths. The church is strongest in the Midwest and weakest in the south; where Baptism rules. Lutheranism is divided into four main branches.

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of America – A very liberal denomination

- Missouri Synod — A more conservative denomination

- Wisconsin Sect — A very conservative denomination

- Mission for Christ — A new, moderate denomination

The ELCA has long been the dominant group in Lutheranism and that continues to hold now. The geographic strength of each is below.

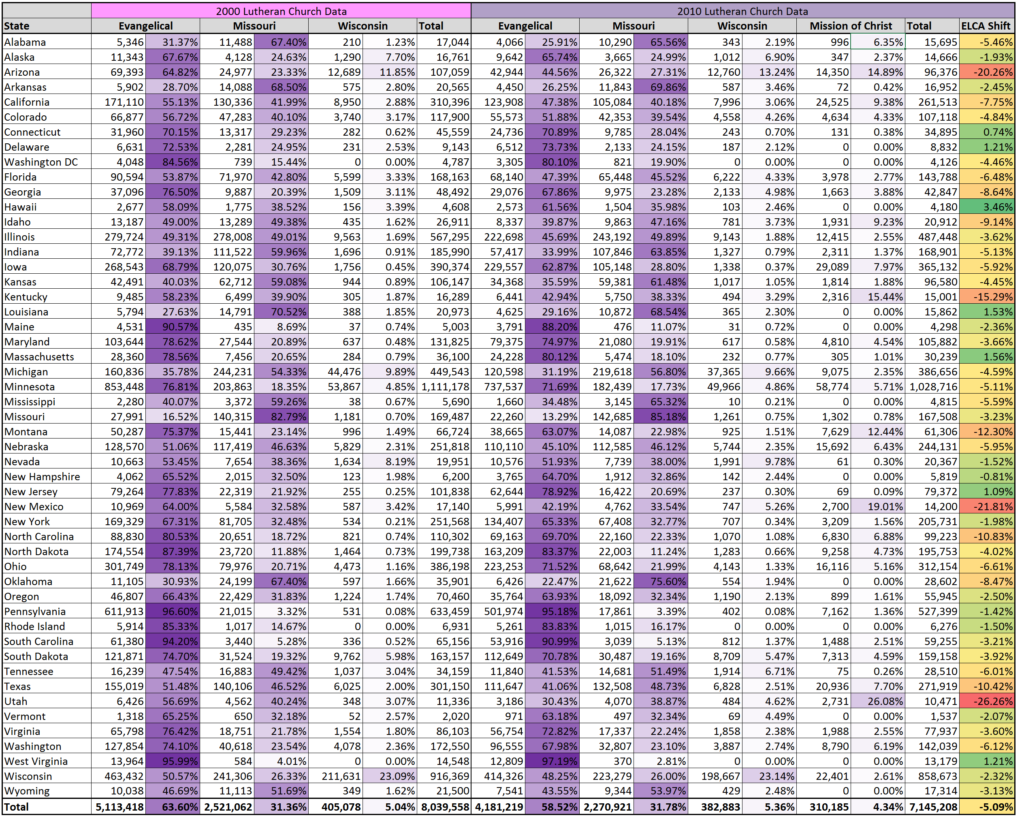

The Missouri Synod is strongest in Missouri and surrounding states and branching out into the west. The ELCA meanwhile dominated in the rest of the country. However, the ELCA has generated controversy in recent years. The church’s liberal positions have caused defections within the organization. The ELCA moving to allow gay priests, support same-sex marriage, and a more pro-choice (before viability) stance have led to many congregations leaving the ELCA. The Mission of Christ is a new Church that formed for these breakaway congregations. The MoC existed for those who felt the ELCA was too liberal but felt the Missouri Synod was too conservative. As the chart below comparing 2000 and 2010 data shows, the ELCA declined the most where the MoC is strongest.

Despite the defections, the ELCA still has a commanding majority of Lutherans in America. It will, however, be interesting to see if the MoC continues to rise when 2020’s study comes out.

Smaller Faith Groups

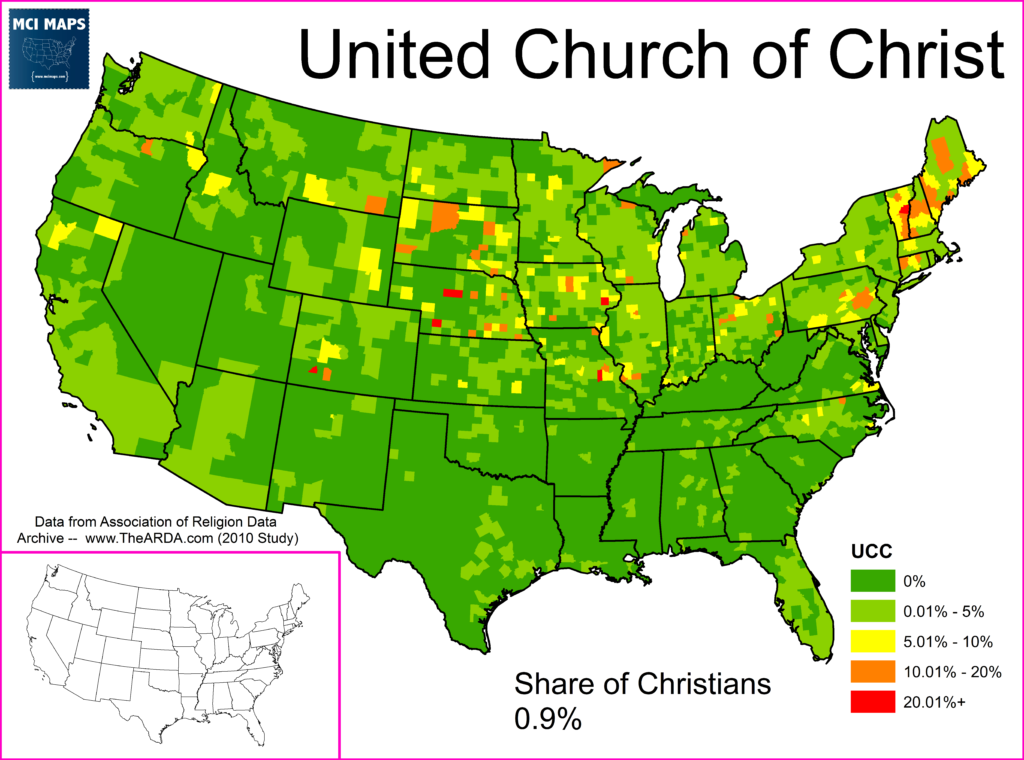

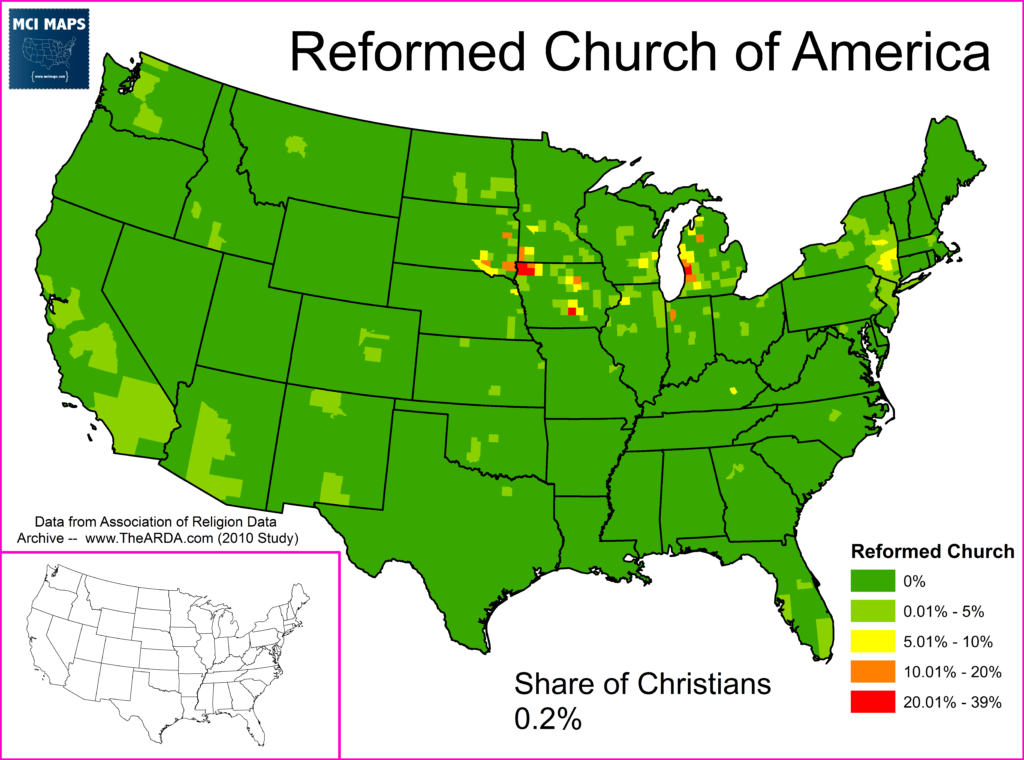

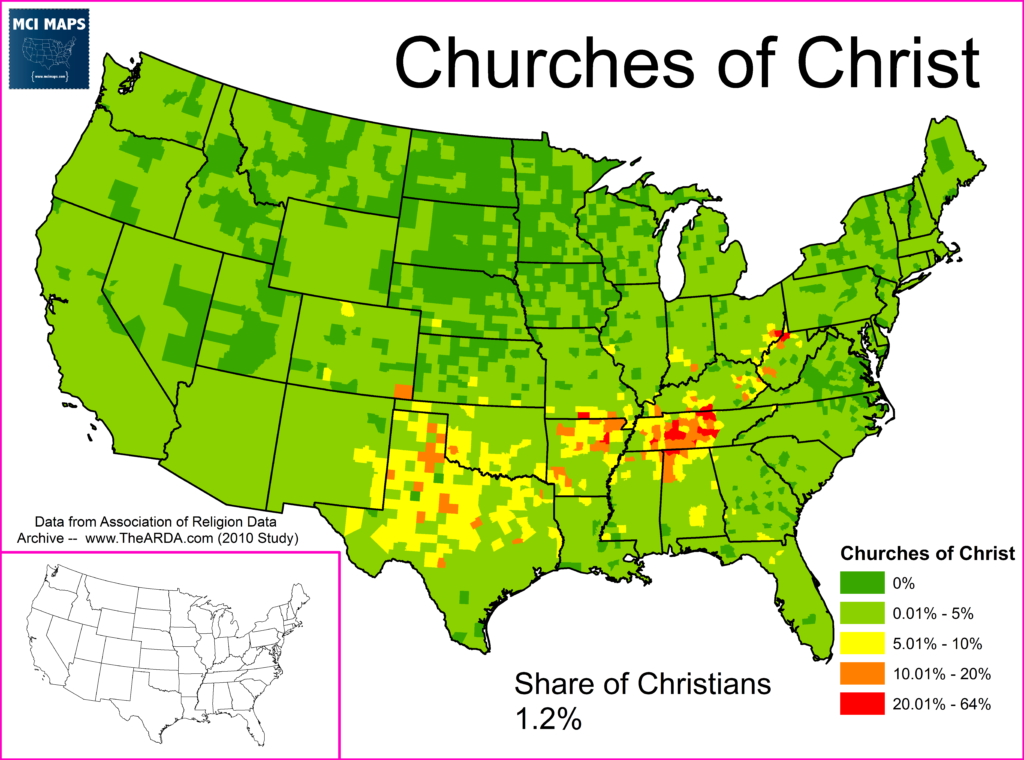

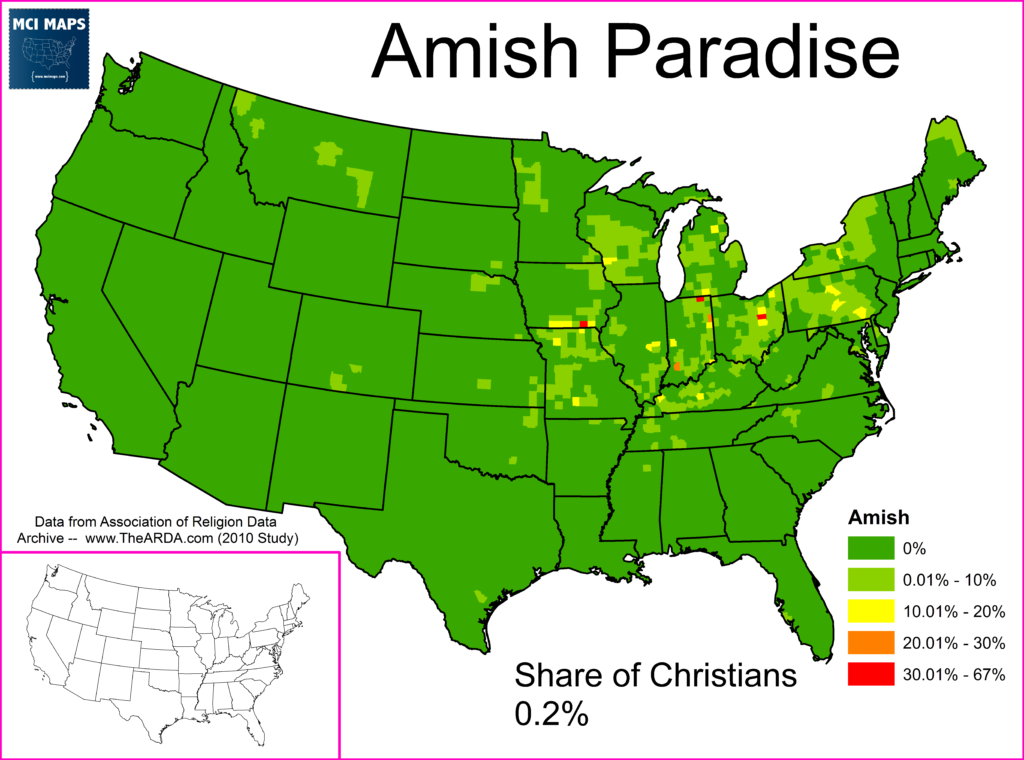

Many parts of the nation have smaller protestant sects that have regional support but are not heavily spread out. A few examples of this are below to highlight the regional base some faiths have. These maps show these groups and their share over Christianity overall, not just Protestantism.

The United Church of Christ, a very liberal protestant denomination, is strongest in parts of New England and select counties in the Midwest but has little reach in the south and rarely tops 20% in any county. The group makes up around 1% of Christianity overall and 1.6% of protestantism.

The Reformed Church of America is a declining sect of Protestantism. The church falls in line more with Mainline Protestantism. As the map shows, its regional strength is very specific.

The Churches of Christ are a loosely-structured group of churches who believe in bible liberalism and overall are very conservative. Many consider themselves protestant while other congregations would argue they are not. Their styles and focus depend on the region, but overall they are a conservative sect of Christianity and their strength in conservative pockets of the country bear that out.

One group few would doubt where geographically isolated are the Amish. However, as the map shows, they aren’t all in Pennsylvania like many from outside the Midwest would suspect. The Amish have a slight presence in many counties of the Midwestern states with several prominent villages in many states.

.

Conclusion

This was just a short overview of Christianity in America. I hope to be able to offer a more complex and detailed analysis in the future. In the meantime once thing is clear; Christianity is heavily split in America. Much of this split is not acrimonious and doesn’t summon up dread here like it does in other parts of the world; areas where such splits lead to violence. Rather, they show a diverse pool of groups and faiths, some with geographic limits and some spread all over. Luther’s break from the church 500 years ago led to a bloody conflict that left millions dead. This was never what Luther wanted. However, the horrors of the reformation wars did cause future democratic governments to stress religious freedom not just for people’s rights, but also to prevent violence. For Christians, the splintering of the Church in America is both a good and bad thing. The goal is a united Christendom, but the facts that these splits largely occurred without major violence (especially compared to Europe) are a clear victory for religious freedom.