The November 7th, 2017 elections saw a huge swath of premier races that got a good deal of state and national attention. Virginia and New Jersey Gubernatorial elections dominated national coverage while Florida’s political press closely watched the St Petersburg Mayoral runoff. However, in Miami-Dade county the most closely watched election was for a $400 million dollar bond measure in the City of Miami.

The bond referendum, dubbed “Miami Forever” by Mayor Tomás Regalado, was the retiring politician’s last big push to cap off the end of his 20+ years as either a Mayor of City Councilman for the city. The measured aimed to use property taxes to fund efforts by the city to combat the rising threat of climate change. The issue of rising sea levels has been a well known issue in Miami-Dade county. The city of Miami Beach has probably garnered the most national attention as it works to combat flooded streets on sunny days. Regalado wants Miami to be as proactive as possible. The proposal he put before the city council called for property taxes (but not an increase in the current tax rate) to fund water pumps, sea walls, and other measures used by Miami Beach and other coastal communities to combat rising sea levels. His initial proposal was $300 million dollars. Estimates said over a $1 billion long-term would be needed for the city to prep for sea level rises. This bond measure was seen very much as a starting point, not the end of the issue.

Regalado put the package before the city commission in July. The bond had already included a combination of funds to combat sea level rising as well as additional funding or parks and affordable housing (a major issue in a city with increasing rents and home values). However, to get the support of commissioner Keon Hardemon, who represents the northern African-American population, the funds for affordable housing was increase from $20 million to $100 million. The final package came out to $400 million – a combination of housing, parks and climate change combating. The vote was expected to be close and the meeting was very heated. The Mayor needed 3 of 5 commissioners to get the measure placed on the November ballot, the same day city council and the open mayoral seat would be contested. Hardemon and Ken Russell, who represents the coastal portions of the city) were already YES. The third vote came from Wlfredo Gort, who represented an Hispanic in-land district. Gort sided with letting the voters having a say in the matter.

Commissioner Suarez opposed the measure, arguing not enough time was given for debate on the details. Suarez was the only major candidate for Mayor in November as well (he would go on to win with 85% of the vote). Commissioner Carollo, who’s termed out, was adamantly against the measure and vowed to campaign against it. Additional opposition came from public employee unions, who argue they are still owed back pay and additional debt on the city will hinder payment. Opposition didn’t center on the issue of if climate change was real. Rather, the opposition revolved around the high price tag and a skepticism the money will be property managed and go to the best programs.

During the campaign, a political group that aims to fight climate change called “Seawall Coalition” put $300,000 into a political committee to advocate a YES vote on the measure. Under the rules of the referendum, the city itself could not advocate for the the measure, only educate on the measure’s details.

Referendum Results

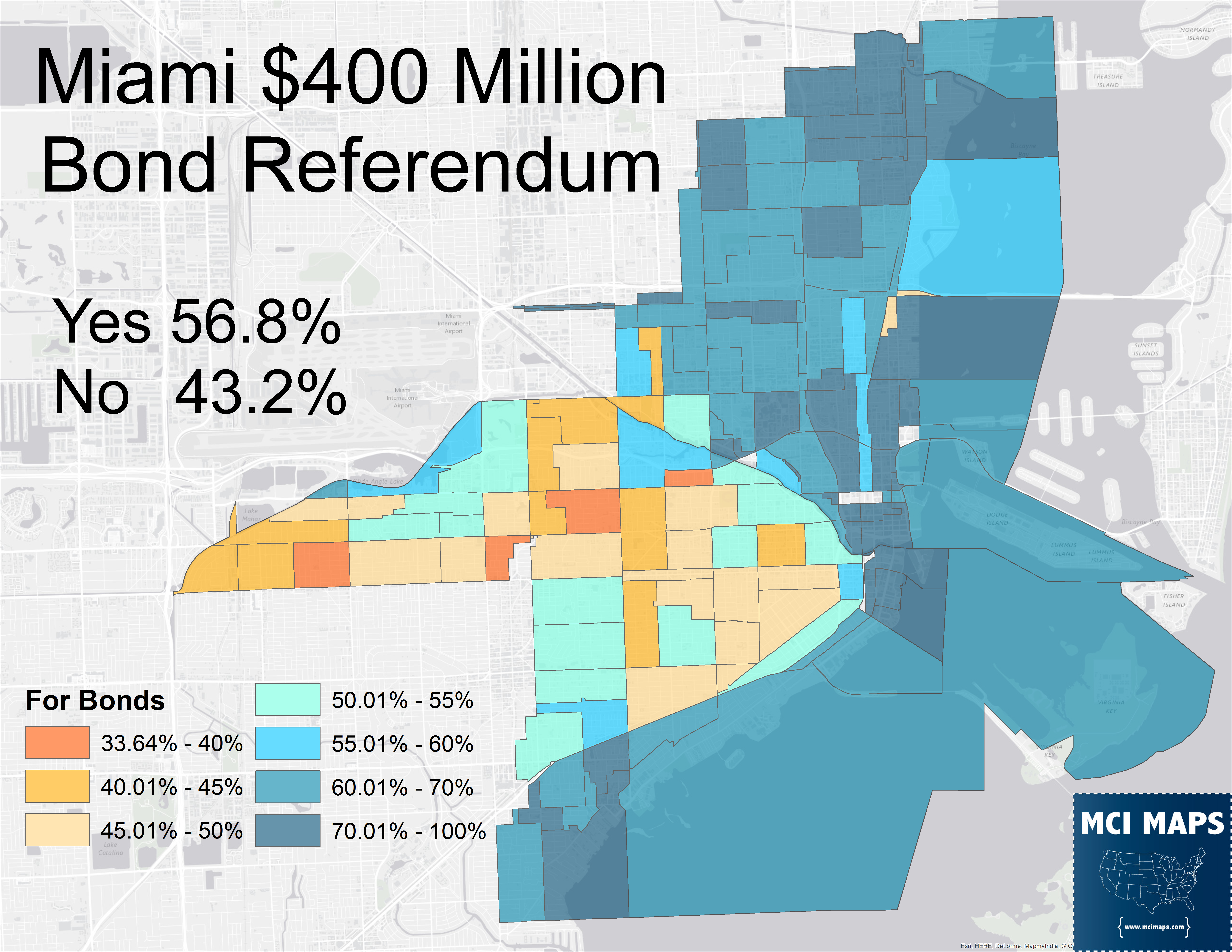

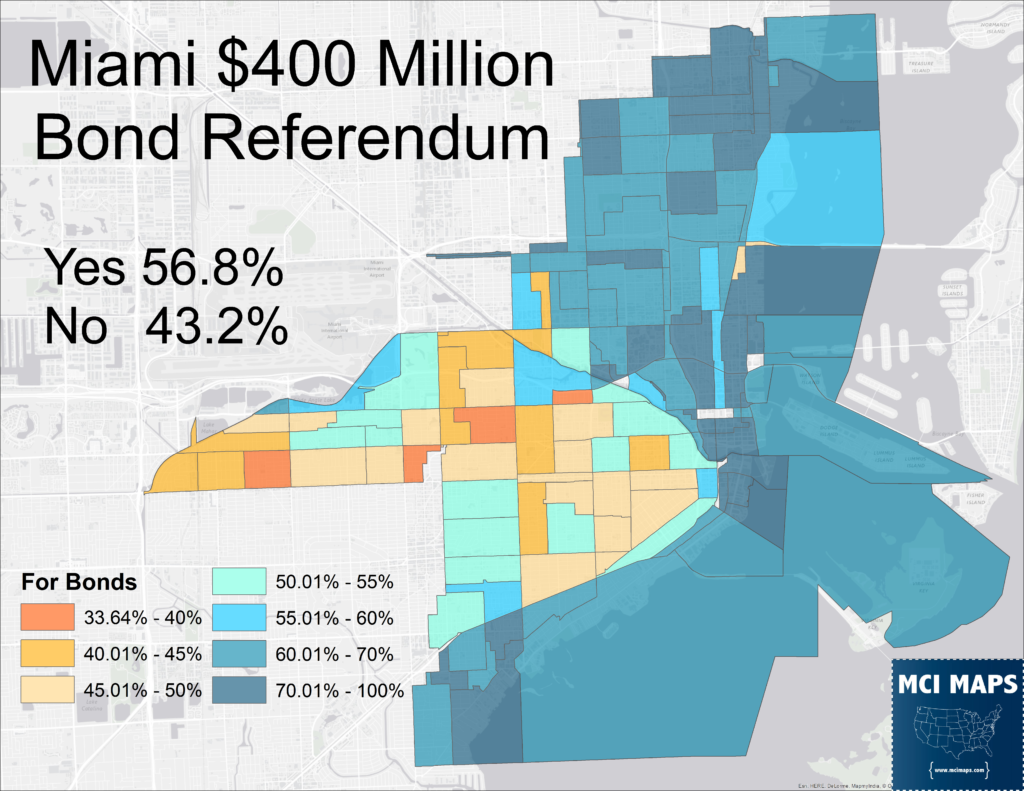

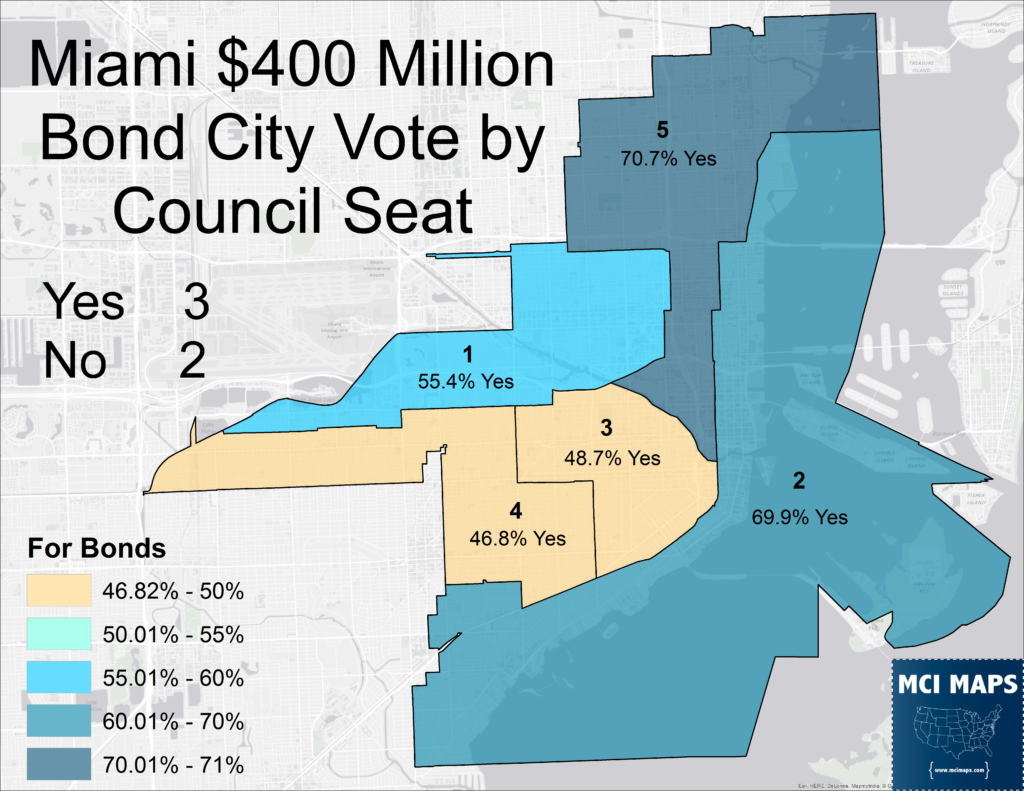

When the results came in, the YES campaign had a modest lead that they held onto through the entire counting process. 57% of the city voted for the bond measure. Support was strongest along the coast and in the northern African-American communities, while weaker inland in more Hispanic-dominated neighborhoods.

The regional spit in the vote sharply stands out. The coasts were overwhelmingly in favor while inland was either weak for it or against it. This vote split matches closely with voter registration in the city.

The white, coastal precincts heavily backed the measure. There’s little shock there since the effects of sea level rising will hit them before anybody else. The African-American precincts in the north also delivered for the bond measure. Commissioner Hardemon’s push for affordable housing funding was specifically designed to help sell his constituents on the measure. Hardemon had argued during the commission meetings that his constituents had pressing affordability issues and that concerns like sea level rise (especially since his seat was not on the coast) would take a back seat to voters who were suffering at that very moment.

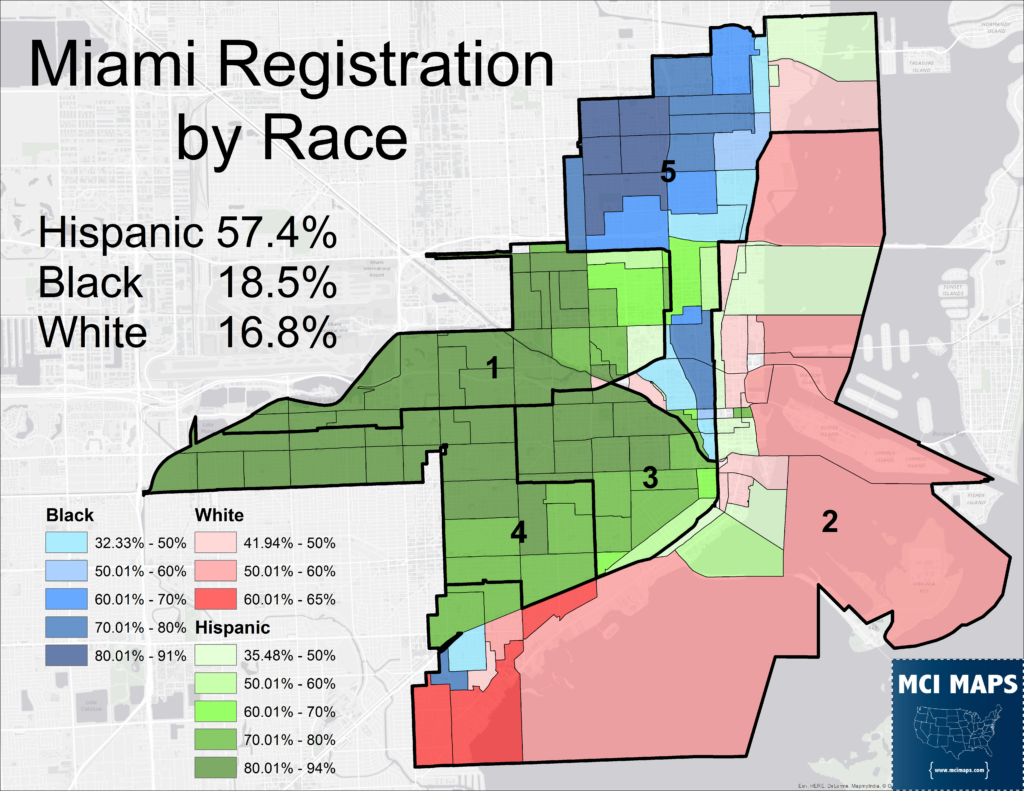

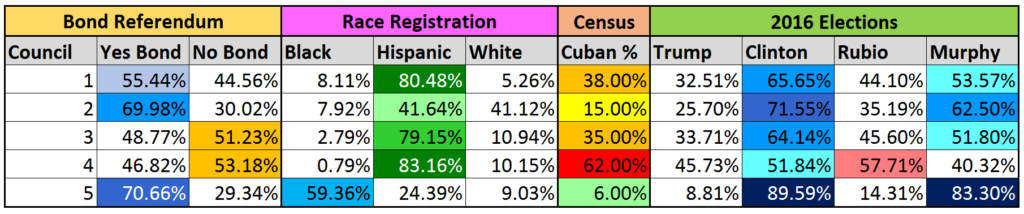

The Hispanic communities were the areas much more split on the measure. Hispanic voters nationwide are generally Democratic and more left on the political spectrum. However, anyone who studied Florida politics knows things are a bit different here. Miami-Dade’s Hispanic population has a large share coming from Cuban voters. These voters are much more conservative; especially the older Cuban voters who disproportional make up turnout in an off-year election. The large price tag as well as a general distrust in the local government’s proper management of the issue no doubt turned off many Cuban voters; even those with a concern for the effects of sea level rise. A map of Cuban estimates of the population are below.

The Cuban areas were much more split on the measure and Cubans make up over half the cities Hispanic population. It can be seen that several heavily Hispanic but less Cuban precincts in district 1 were more in favor of the measure.

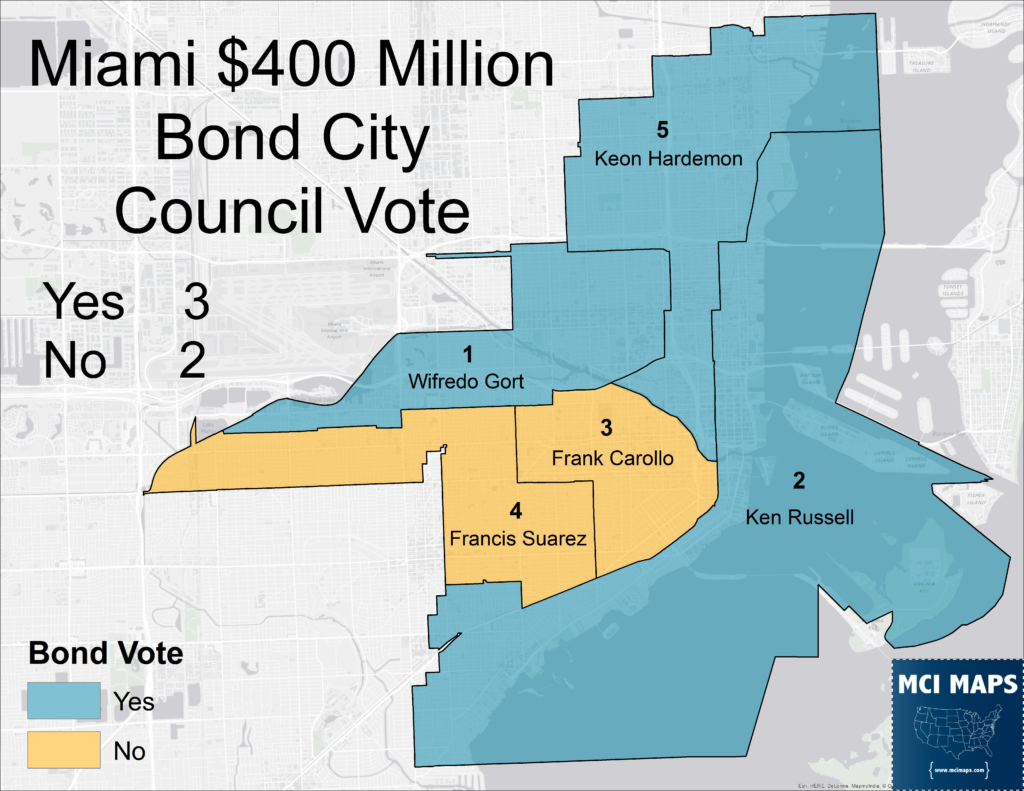

How the vote broke down by city council seat is below.

The vote breakdown by council seat perfectly mirrored how the council members voted on the measure. Suarez’s district has the highest Cuban share of the its population and that is reflected in the lowest Yes support for any of the districts. Meanwhile, despite Carollo’s strong dislike of the measure, it barely failed in his district. Gort’s district 1 passed the measure by a modest 55% thanks to strong support from less Cuban precincts in the east in addition to decent showings in the more Cuban west. Russell and Hardemon both saw their districts give 70% support to the measure.

More details of these districts can be seen in the chart below. Three of the city’s districts are overwhelmingly Hispanic. However, district 1 backed the measure while 3 and 4 said no. The 4th seat is no doubt the most conservative of the five thanks to being the most Cuban. While it backed Clinton narrowly in 2016, it gave Rubio a 17 point margin in the US Senate race. Council Seat 1 appears to have a larger Cuban population than Council 3 (though these are estimates because census tracts and the council seats dont match) but nevertheless appears to lean a bit more to the left.

When it comes to the referendum, one reason for the difference in council 1 and council 3 is the position of the commissioners plus the fact council 3 had an open commission seat to boost turnout while council 1 did not. The mayoral election was a blowout that everyone knew Suarez would win and the bond measures were heated but did not feature major GOTV efforts for. Indeed turnout in district 1 was 9% compared to the 16% in district 3. Turnout was also around 10% in districts 2 and 5, which featured no city council races while District 4 saw 16% turnout as well thanks to its competitive council election. Since turnout is almost always weaker with Hispanics in off-cycle races, it could be that more Hispanics and Cubans did not cast ballots in that seat. We won’t have final turnout figures for a few weeks.

Conclusions

The success of the measure is a final victory for Mayor Regalado as he prepares to leave office. Preparing the city for sea level rises as been a major priority of his for the last several years. The politics of the council vote and the referendum should be looked by other cities considering such efforts. Local community issues and trust in the local authority will determine a great deal of how the vote shakes out, not just an abstract view of the issue of climate change.