Miami Beach is many things to many people. For many its a great place to retire right on the beaches. For middle aged folks its a tropical paradise to raise a family in. For locals and visitors its a place to party and have fun. For college students its the site of legendary South Beach. Miami Beach’s reputation for its night life and party scene has been part of its identity for decades. Establishments across the city have last call at 5am vs the traditional 2am you see in most of the state. The iconic Ocean Drive (next to South Beach) has an active club and nightlife scene that brings in money and tourists year round.

For some reason that iconic nightlife bothered Miami Beach Mayor Philip Levine.

The Ocean Drive Referendum

Philip Levine has had a problem with Ocean Drive for much of his mayoral administration. Levine has seemed obsessed with this issue for for some time; pushing for a change in the closing time for multiple years now. The area is home to several iconic outdoor clubs (aka not confined inside walls). Like with any large gathering of people, crime has occurred. A shooting and stabbing over Memorial Day weekend cause Levine and the commission to push his proposal to reduce the last call time at these outdoor clubs from 5am to 2am. Levine has claimed for years Ocean Drive is riddled with crime. However, the city’s own crime data says over 95% of crime happens away the area. Levine has argued that the late last call time attracts unseemly folks into the city on the weekends and that reducing the last call time would reduce this migration of folks from outside the city. This type of talk of outsiders coming in was distressing considering the unsaid part of all this is many/most of the folks that come into the city for the night life are African-American. Of course the businesses in the area argued that reducing the flow of people would hurt the economy of the city and wouldn’t actually reduce crime. Another major critique was that Levine’s proposal only reset the last call time in the outdoor establishments on Ocean Drive; leaving 5am last calls for indoor establishments on the road and other establishments across the city. The notion that crime would be reduced by the change is very disputable since most crime in the city occurs far outside Ocean Drive. Nevertheless, Levine got the council to agree to put the binding measure on the November 2017 ballot to let the voters decide.

The response was an overwhelming no.

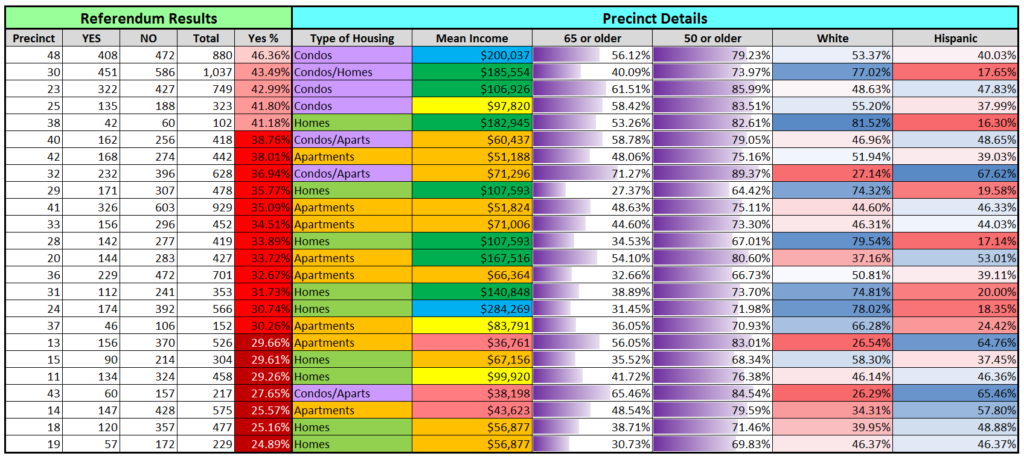

Every precinct in the city rejected the change. Precincts right along the region of Ocean Drive and South Beach that would have been effected gave the measure less than 40% support. The closest the measure came to passing was in the southern tip of the city.

Breaking Down the Vote

What is especially notable is that major neighborhoods in the north end of the city, areas not dependent on a vibrant Ocean Drive, were strongly against the proposal. What we might call “suburban” precincts made up of nice houses weren’t swayed or scared by the prospect of “scary people” flooding into Miami Beach either.

There were, however, a handful of precincts that got close to or cracked 40%. I wanted to investigate why that was.

The map below shows the precincts color-coded by two key factors. The left map classifies the precincts by the primary source of living arrangements in the precinct. Many precincts are predominantly traditional homes. Others are largely made up of apartment or townhouse developments. Third, several precincts are predominantly high-rise condos. A handful of precincts were fairly split between two types of residency so I listed them as both. The map to the right classifies the precincts by the median household income.

One variable really stood out when it came to support for the referendum. Precincts predominantly made up of condos were much more in favor of the change in Ocean Drive than the rest of the city.

Most condo-dominated precincts topped 40%. Only precincts 32 and 43, which are a mix of condo’s and apartments fell below 40%. Precinct 43, located right on Ocean Drive, was all the way down at 28% support. This precinct is a mix of some beach-area condos and apartments, but these are not the fancy high-rises and the mean income was only $40,000. Meanwhile, precincts 48, 30, and 23 were condo precincts with mean income over $100,000 and all gave YES 43% or more. Precinct 48, the highest YES vote, is dominated by high-rise condos and has a mean income of $200,000.

Condo’s and secondly income had the biggest impact on a Yes/No vote. Even income is very much secondary. Several high-income precincts that were house-dominated gave the measure terrible support. Precinct 24 is a house-dominated precinct with a mean income of $284,000 but only gave YES 30% of the vote. The one example of a house-dominated precinct giving the measure decent support was precinct 38, which has a mean income of $183,000. The caveat for this precinct though is its partially made up of the gated community of Star Island.

The chart below lays out the referendum results by precinct as well as income and housing classifications. I included some race and age data (estimates as we don’t have final turnout figures yet). However, I found little correlation with either of those data points.

I was surprised age didn’t have a greater correlation. But we have several very old precincts that did not support the measure. Of course the reality is every precinct has a large elderly population, so comparisons are tricky. Of course the condos are predominantly resided in by older voters.

While there has been plenty of anecdotal discussion about white voters or Jewish voters supporting the measure, the data only somewhat backs this. Jewish voters are too scattered in the precincts to analyze. While Miami Beach was once predominantly Jewish, its total share of the population has fallen to below 20%. As far as I could tell, no one precincts was predominately Jewish. As for whites in general, several heavily white precincts were strongly against the measure; granted those were apartment or house precincts. Whites in condos did however seem to be much more in favor; like in precinct 30.

Heavily Hispanic precincts largely gave the measure a poor showing, including Precinct 43, which is partly condos. We don’t have final turnout data yet but there is some argument to be made whites likely backed the measure more than Hispanics. However, part of that again goes back to the housing. Heavily white precincts made up of homes barely cracked 30% yes while heavily white condo precincts were much more supportive.

Looking at the results of the referendum by voting method, we see YES came closest (42%) in the vote by mail. One item that really stood out when comparing vote by mail ballots vs other methods what the share of that vote that came from condo-heavy precincts.

As the chart shows, condo’s made up a far larger share of the VBM vote than early or election day.

Why the Condos

So the question is, why was condo ownership so important in YES getting a higher % of the vote than other precincts. I think it comes down to two important items.

- Demographics. Condo owners in areas like South Florida are a unique demographic. Many are retirees from out of the city. Concerns about crime would be high and an attachment to the “historic Ocean Drive scene” wouldn’t be as strong a factor compared to folks that grew up in and around the city

- The campaign. A committee was formed to stop the measure from passing, “Citizens for a Safe Miami Beach.” The committee raised and spent a staggering $700,000. TV ads, radio ads, direct mail, phone calls and canvasing were all utilized to convince voters to vote no. While TV and radio could hit condo voters, canvassing could not. These were professional operations as well. Recent finance report (which don’t account for the last few days of spending) show over $45,000 spend on canvassing operations. The final figure spent on canvassing will likely be over $60,000 when the final reports come out. However, anyone familiar with campaigns knows condos are hard to walk. Security makes it impossible in some cases. This means these voters didn’t get the full brunt of the opposition campaign that the rest of the city got.

Conclusions

It is not unfair to say to say Levine seemed obsessed with the issue of Ocean Drive. Constant accounts from businesses and politicians point to Levine having it out for the clubs of the area. Levine even yelled at one club owner to “get a real job” during the debate over the issue. Levine’s obsession resulted in a major rejection just as he leaves office to run for Mayor. In the end voters agreed that the referendum would not solve crime issues and would harm the city’s economic and tourist image. At the end of the day, the referendum was not only misguided policy but also a stunningly poor political calculation from a politician with statewide ambitions.