If you have been following my twitter and substack over the last several weeks, you know Florida is in the middle of redistricting. The legislature is now in session and maps must be passed in the next several weeks. Things appeared to be moving long smoothly, with the Senate and House working on respective drafts for Congress. The two chambers have differences, especially in Orlando, but in much of the state the two sides were on a similar track. The Senate passed its proposal a few weeks back.

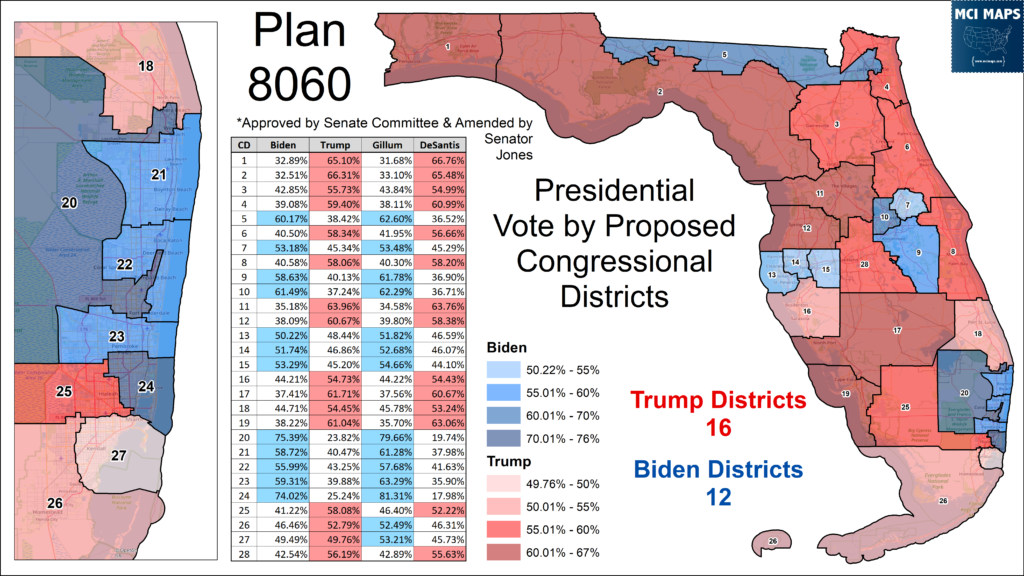

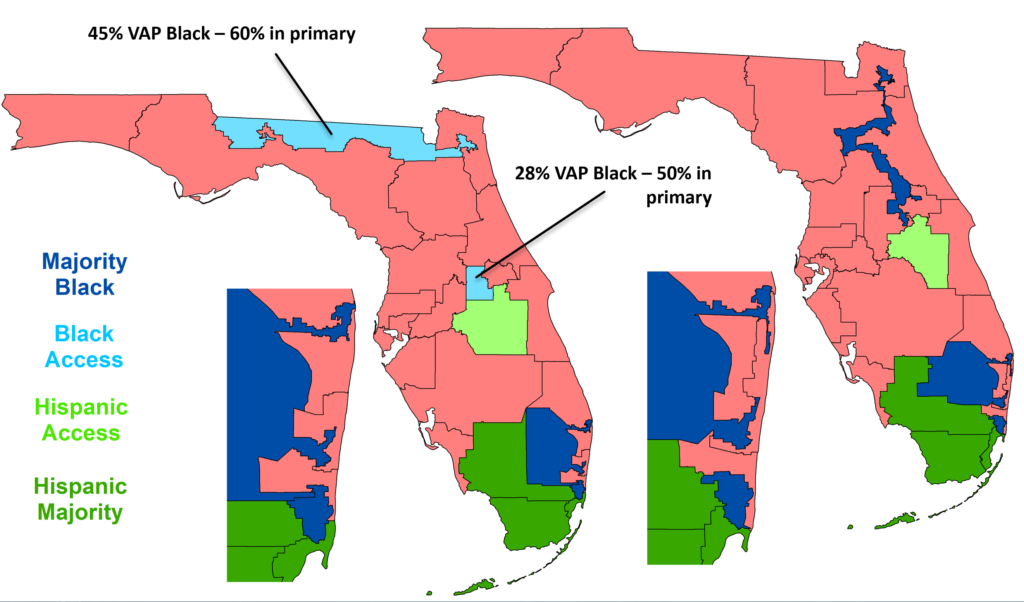

Both the House and the Senate were in agreement that the African-American performing 5th, 20th, and 24th would be preserved. The Senate also views the 10th as a protected African-American seat, while the house doesn’t. It appeared that would be the main source of debate. THEN, Governor DeSantis released his own proposal.

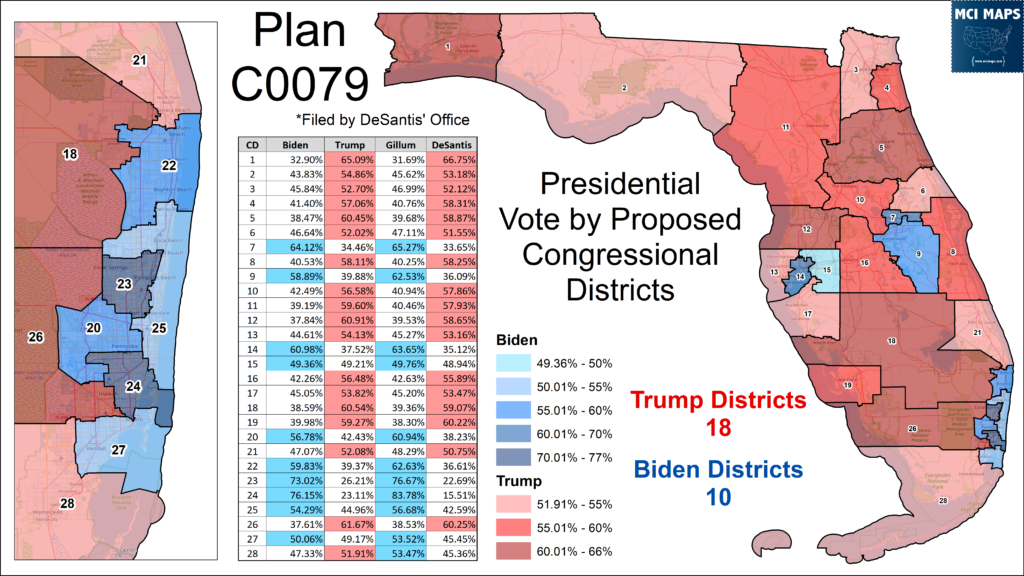

DeSantis offered up his own plan for consideration, and its a nasty gerrymander if you ever saw one. The seat removes two of Florida’s four African-American districts. DeSantis and his admin claim the 5th is not protected and should be demolished. This was fodder for conservatives on twitter; who have been clamoring for an aggressive gerrymander.

I’ve been covering the back and forth over redistricting in my substack newsletter. This article will focus on one specific issue; the 5th Congressional district. I am going to lay out the history of redistricting in North Florida and go over how we got to the modern 5th district we have today.

I highly… highly…. highly recommend re-reading my Florida Redistricting History series. This article will cover many points that I delve into in much greater detail in that series.

History of the 5th District

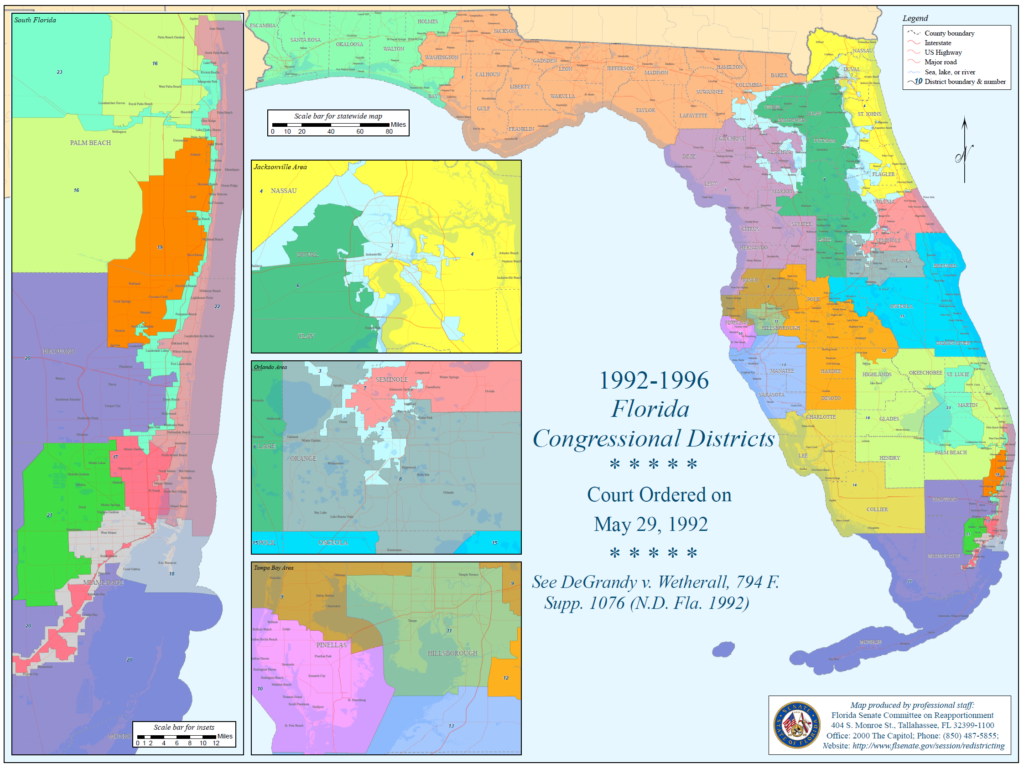

The story of the 5th begins with 1992 and the emergence of minority districts in Florida. This was a complicated time, so lets go through it piece by piece.

The 1992 Redistricting Process

The story of the 5th district stretches back to the 1990s. It was in this decade that many of the current VRA-protected minority districts were drawn. A combination of the 1982 VRA Amendment, new computer technology, and an aggressive DOJ led to many states being mandated to draw minority districts. This mandate stemmed from post-Jim Crow states allowing minority voting, but cracking African-American voters to deny them Representation. This same saga took place in Florida’s 1982 redistricting process; with white Democrats drawing seats to be 20-30% black. These seats ensured districts remained Democratic, but left black democrats with little chance to elect candidates of their own choosing.

The 1990s redistricting process was an incredibly contentious process in Florida. The Democratic-led legislature was eager to preserve its power; which was slowly slipping away as the FL GOP rose in strength. The 1992 redistricting saga is so contentious that I highly recommend reading this detailed breakdown of events. The shortest version ever is

- Black Democrats, sick of cracking, wanted minority seats drawn

- Republicans tried to push for maximum minority districts, hoping to bleach everything else

- White Democrats desperately tried to cling to their power and limit minority seats

- Black lawmakers/activists themselves were divided on how far to go in minority seat numbers

- The legislature could not come to an agreement on Congressional plans due to conflicts within the Democratic caucus and the House and Senate did not trust each-other

- A 3-judge panel for the Federal Northern District of Florida appointed a special master, Judge Clyde Atkins, to get a map drawn

- Atkins had Tulane Professor David Gelfand work on creating a plan. Both heard testimony from all stakeholders – who submitted plans themselves

- A final plan was drawn: with three African-American districts and two Hispanic districts.

The three minority districts were as follows

- FL-3: 50.6% non-Hispanic Black VAP

- FL-17: 51.3% non-Hispanic Black VAP

- FL-23: 44.4% non-Hispanic Black VAP

- FL-18: 67.5% Hispanic VAP

- FL-21: 70.6% Hispanic VAP

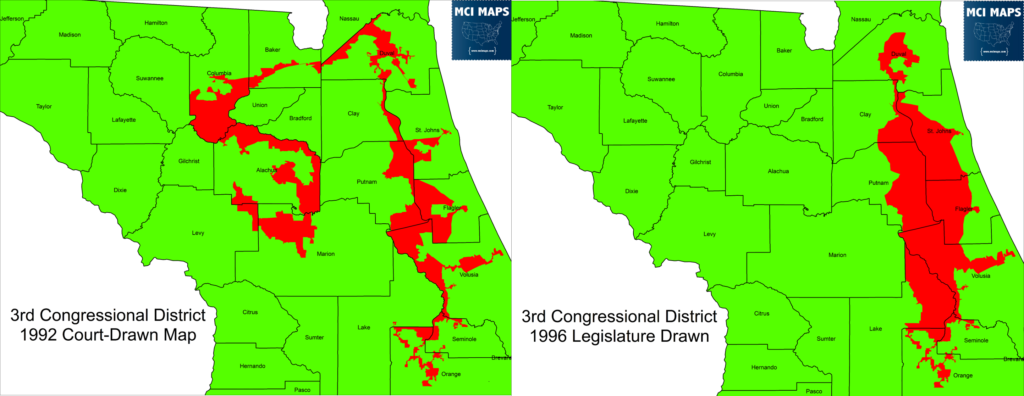

More detailed views of the Florida 3rd are seen below.

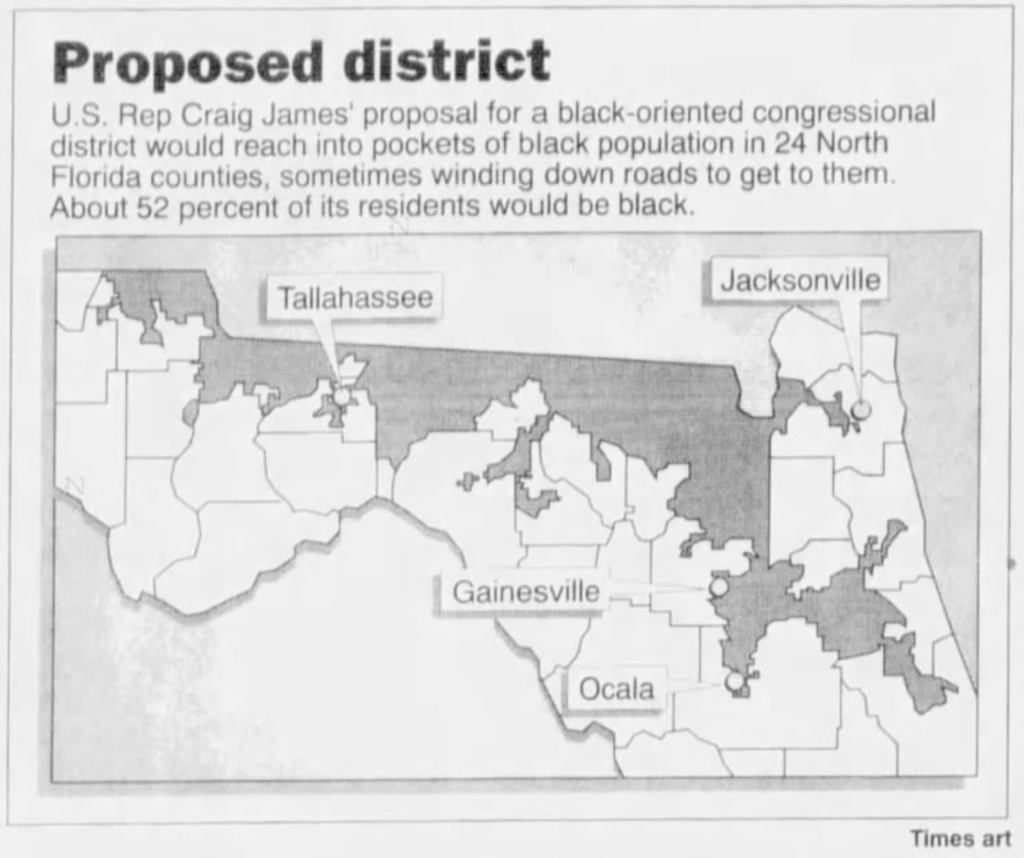

This seat looks insane, I agree. It took all that just to create a 50% BVAP district. When redistricting was being debated in the legislature, many plans on how to draw a minority district in North Florida were debated. One proposal from Republicans was more east-west but also dipped south.

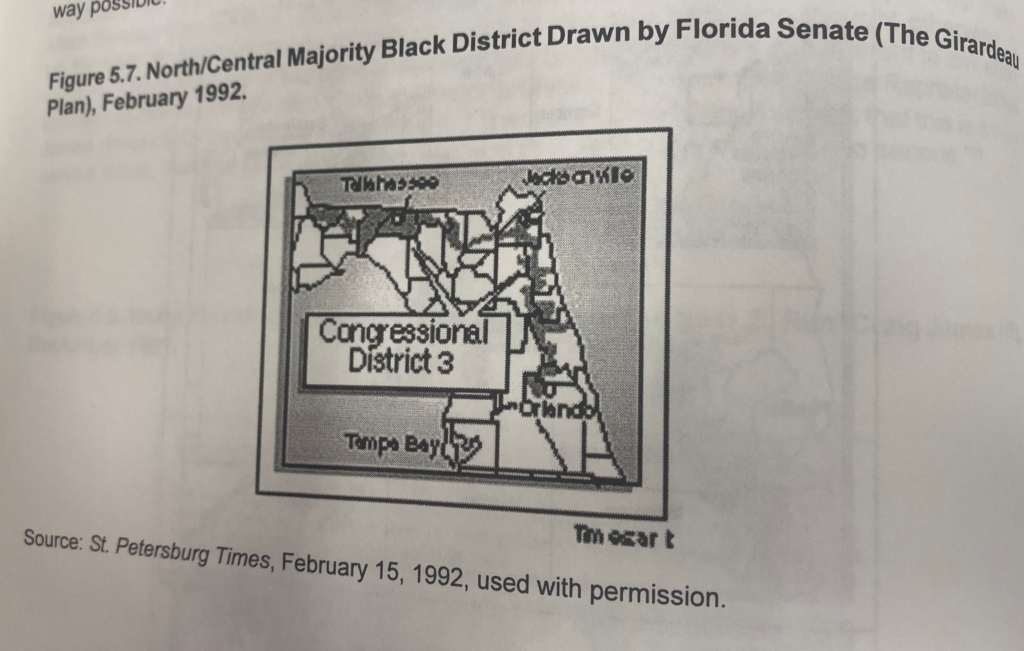

In the State Senate’s plan, CD3 was majoirty-black and stretched from Tallahassee to Jacksonville and then to Orlando.

The court-chosen CD3 was really no worse than the other districts proposed by lawmakers. All had bizarre shapes. There were partisan motivations behind the two proposals above. The GOP-backed plan aimed to short-circuit Democratic strength in the panhandle. The Democratic-backed plan tried to create a minority seat that would loop around other white-dem seats. Again I delved into these motivations much more in my 1992 redistricting article.

1992 and 1994 Elections

The court-mandated plan went forward for the 1992 and 1994 elections. However, as that went on, lawsuits were in the works over the district. The 1992 redistricting process had produced many oddly-shaped districts across America. Defenders of the oddly shaped seats were that they were the only way to ensure long-silenced minority voices would finally have the representation that had been denied for decades. This especially held true in the southern states.

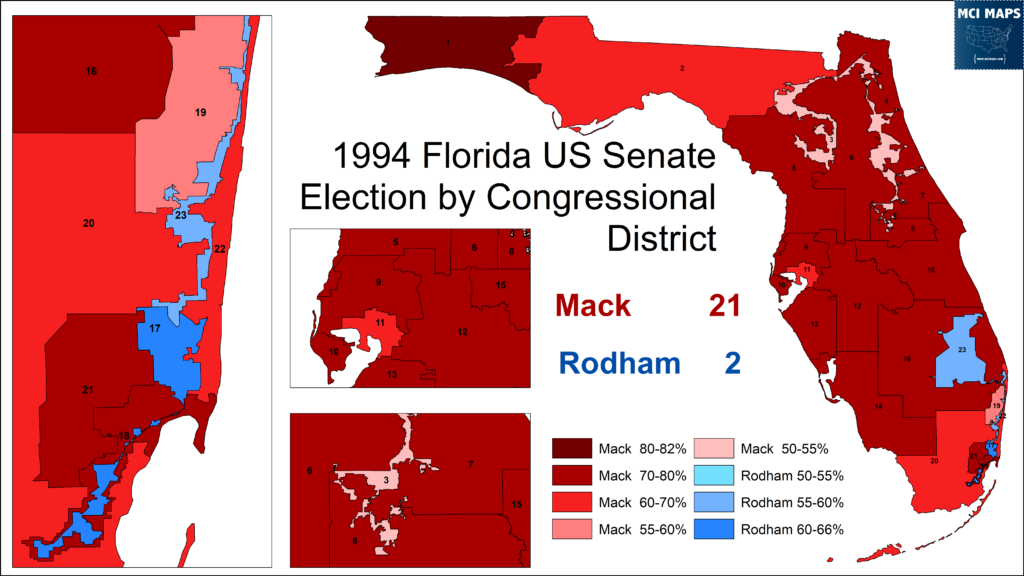

In 1992, Democratic State Rep Corrine Brown would win the primary and general for CD3. Her election, along with Carrie Meek and Alcee Hastings, would make the first time Florida had black congresspeople since reconstruction. Defenders of the 3rd would site that the seat wasn’t as packed as the lines suggested. The 1994 election saw Brown secure 57% in her re-election while Republican US Senator Connie Mack actually won the seat in his landslide re-election.

Defenders of the 3rd would argue that the Mack win, along with Brown’s modest re-election, meant the seat’s shape was needed to ensure minority performance. However, the seat’s shape would eventually fall in court.

The Supreme Court and VRA Seats

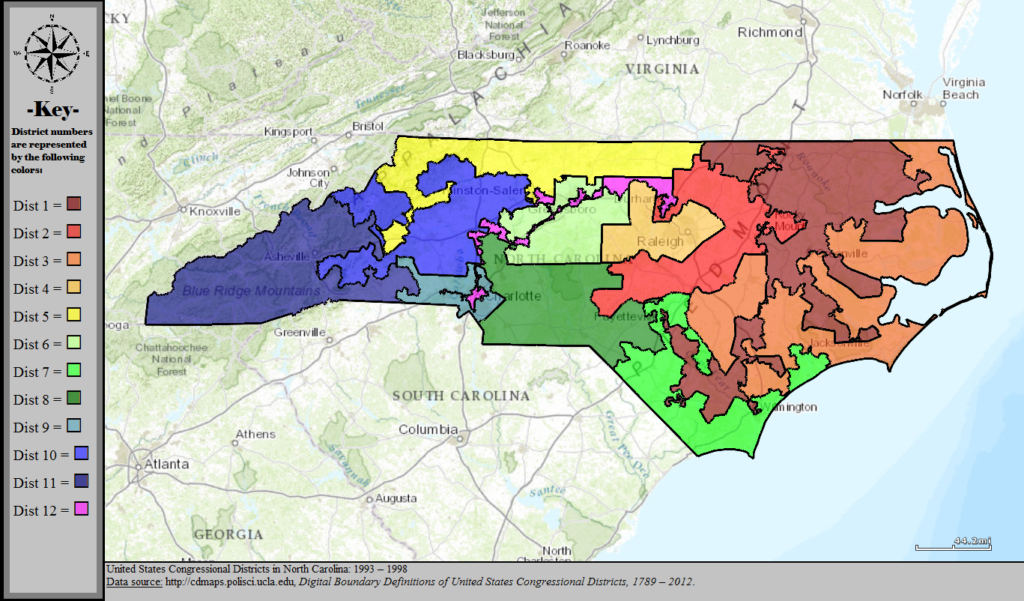

After the 1992 redistricting process, several lawsuits made their way to the Supreme Court. These cases would set standards to balance minority interest with bizarre district shapes. The first case was Shaw v Reno (1993). In this case, the 12th district of North Carolina was struck down. This is a well-known example in terms of oddly shaped seats. The district is really just a narrow snake going around the state and grabbing pockets of black voters.

In the Shaw case, Justice O’Conner wrote that such race-based districts are subject to strict scrutiny, meaning they must satisfy three conditions: a compelling government interest, narrowly tailored to achieve the goal, and use the least restrictive means to achieve the goal.

Another major case was in 1995 with Miller v Georgia; where the Georgia 11th was struck down.

In the decision, Justice Kennedy wrote

“a reapportionment plan may be so highly irregular and bizarre in shape that it rationally cannot be understood as anything other than an effort to segregate voters based on race”

Miller v Johnson ruling

With these cases, the 3rd district was clearly at risk. In 1995, a lawsuit over the seat, Johnson v. Mortham, saw a 3-judge panel strike the district down. The legislature was tasked with drawing a new district for the 1996 elections. Again, read my 1992 redistricting article for more court details.

1996 Remap

The remap came as a time of divided Government in Florida. Republicans controlled the state senate while Democrats held the house and Governor Chiles held a veto pen. The debate over the new 5th largely centered on whether to draw an east-west configuration (Jax to Tallahassee) or north-south (Jax to Orlando). At no point was the idea of eliminating the 3rd as a minority district considered. Court cases had not struck down minority districts, but rather how they were drawn. The decision came to do a north-south configuration.

This new 3rd district still had odd appendages, but was overall much more compact. It went from 50% BVAP to 42%, but continued to perform as an African-American seat for the rest of the decade.

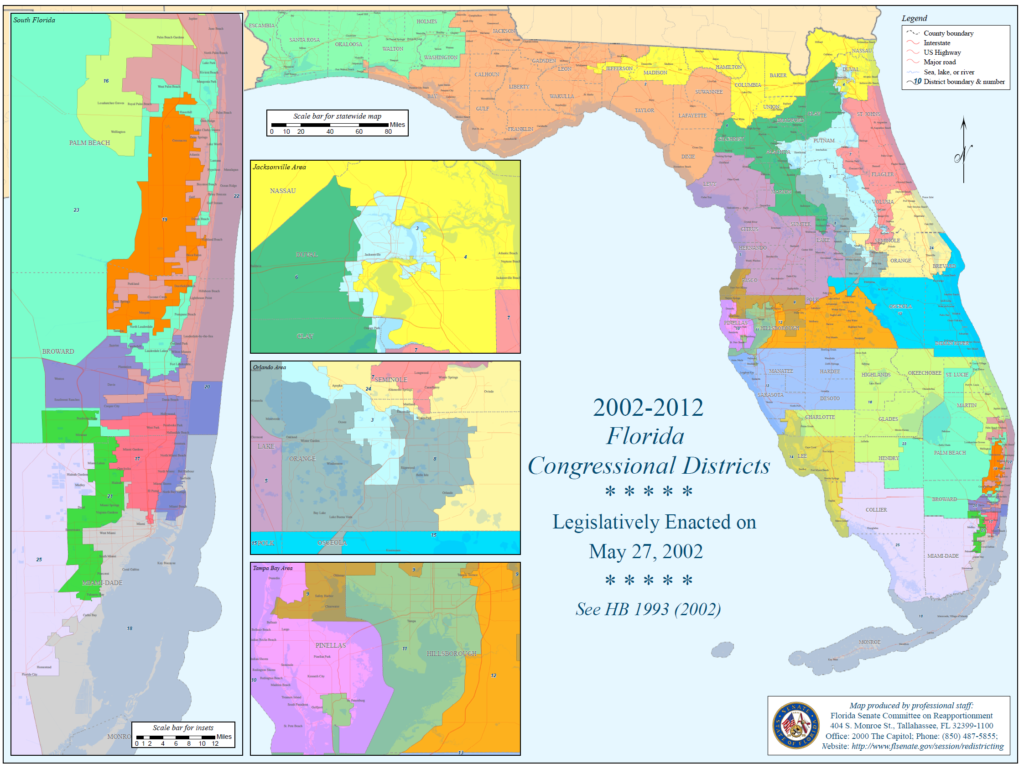

2002 and 2012 Mapping

The 2002 redistricting process (read my detailed history here) saw some changes to the 3rd district, but its nature largely remained the same. Republicans continued to the North-South alignment, also moving into into Gainesville.

The district was 46% African-American voting-age population in this iteration. No lawsuits succeeded in striking it down. The district was defended via its functional analysis – which showed the seat was very Democratic and the Democratic primary was over 60% black.

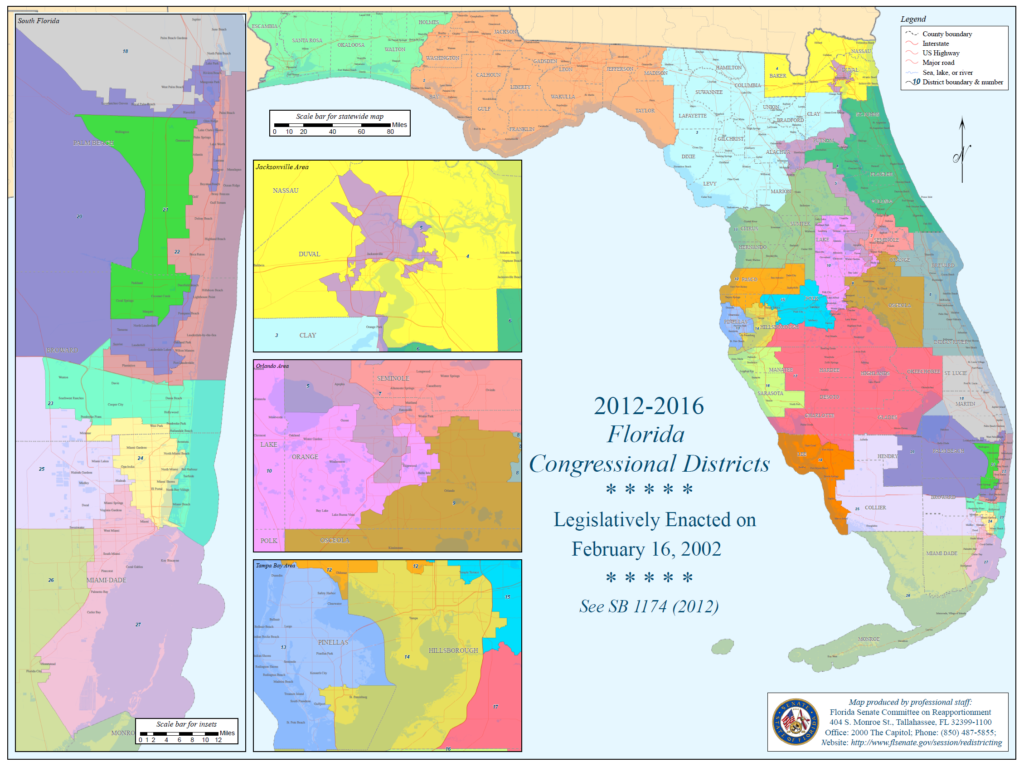

In the 2012 redistricting process (detailed history here), the 3rd was changed to the 5th. It continued its North-South divide, with the seat increasing to 49% African-American. The district was under greater scrutiny, as Democrats viewed Republican efforts to pack the district with growing non-white voters.

The North-South configuration was the greatest source of debate. Democrats and their allies asserted that this layout prevented a possible new minority seat in the Orlando area – while the 3rd/5th (whatever number you want use) could remain as an east-west seat. Republicans rejected this claim, as did Congresswoman Corrine Brown. However, it was later revealed that the legislative staff had investigated an east-west proposal and drawn up an un-released plan.

After the 2012 maps were passed, a coalition of plaintiffs sued the state over its proposal. These suits were brought under the newly-passed Fair Districts Amendments. Read more about those reforms here.

2014 Trial and 2015 Court Order

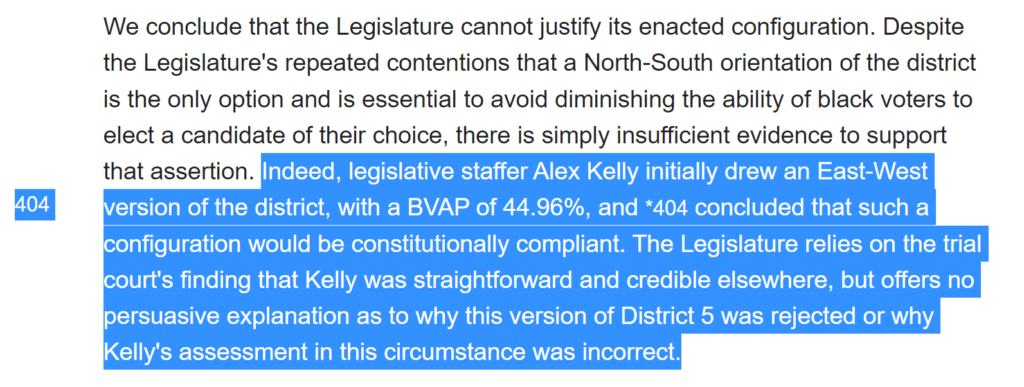

The status quo would come to an end in 2015, however. The coalition plaintiffs challenging the map as a political gerrymander; barred under the Fair Districts proposals. The subsequent trial revealed Republicans had, indeed, worked behind the scenes to ensure they passed a GOP-performing map. The trial and appeals eventually made their way to the Florida Supreme Court, who ordered a new map and specifically struck down several districts.

The trial and discovery revealed GOP ill-intentions. As a result, the court declared the legislature had no right to deference in drawing a new map. Lawmakers were on thin ice, and given direct orders with many districts. One big order was that the 5th would be drawn east-west. You can read the entire opinion here.

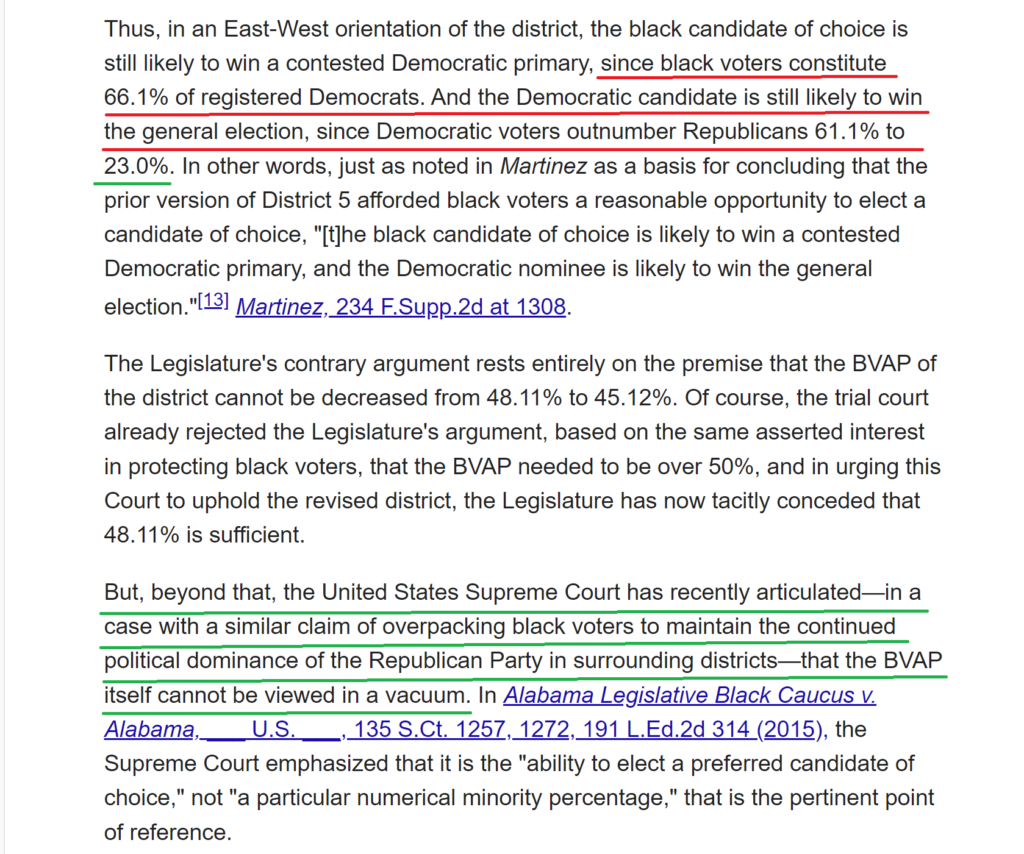

The legislature’s main argument for their version of the 5th was that the higher African-American share of the vote that you get from North-South was needed to avoid retrogression. The court rejected this, cited Supreme Court cases that showed census-level data was not the only metric for determining minority districts.

The case highlight the functional analysis – which showed how an east-west district would be over 65%+ black in a Democratic primary; and the Democratic primary winner was almost a lock in the general. This electoral-based analysis is a major function of redistricting.

2015 Redistricting Special Session

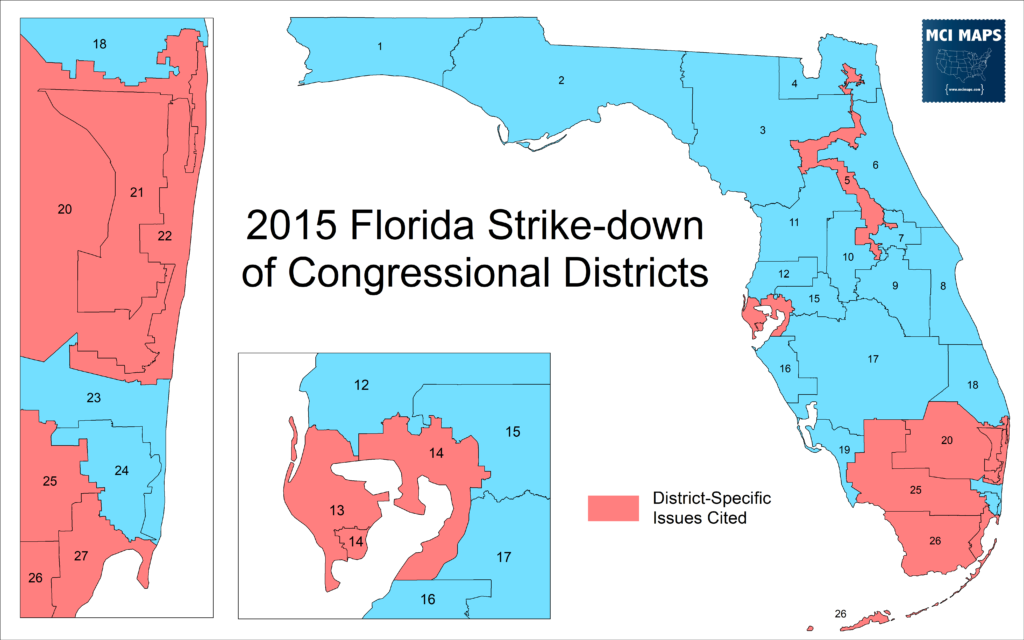

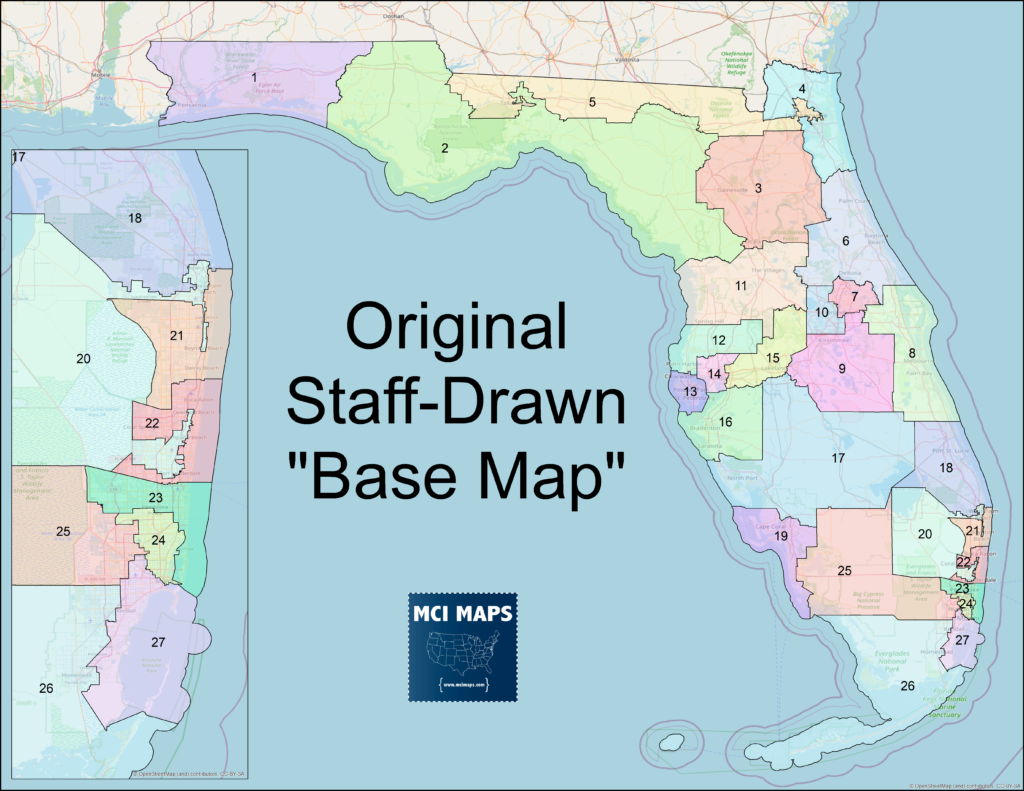

With the court order, the legislature went into special session to redraw the lines. All of the back and forth is covered in my 2015 redistricting review article. Lawmakers would debate many regions of the state; however, the 5th district was one of the least-debated points. With the court citing a specific FL-5 layout provided by the plaintiffs, the legislature opted to put that layout in their proposal. When the first “base map” was released by legislative staff, it include the court-cited 5th.

The special session largely revolved around other regions of the state. There was some debate over other ways to set up an east-west 5th, but those alternative proposals would not be adopted. As this was going on, Congresswoman Corrine Brown was kicking and screaming about her district changes. Brown made several easily-disproven claims; namely that the proposed 5th wouldn’t perform for African-Americans. I delved into this more in my 2015 article. Eventually the house and senate would be unable to come to an agreement on a final plan; forcing the court to pick a proposal. At no point in disagreements was the 5th the source of debate. Everyone agreed on that layout.

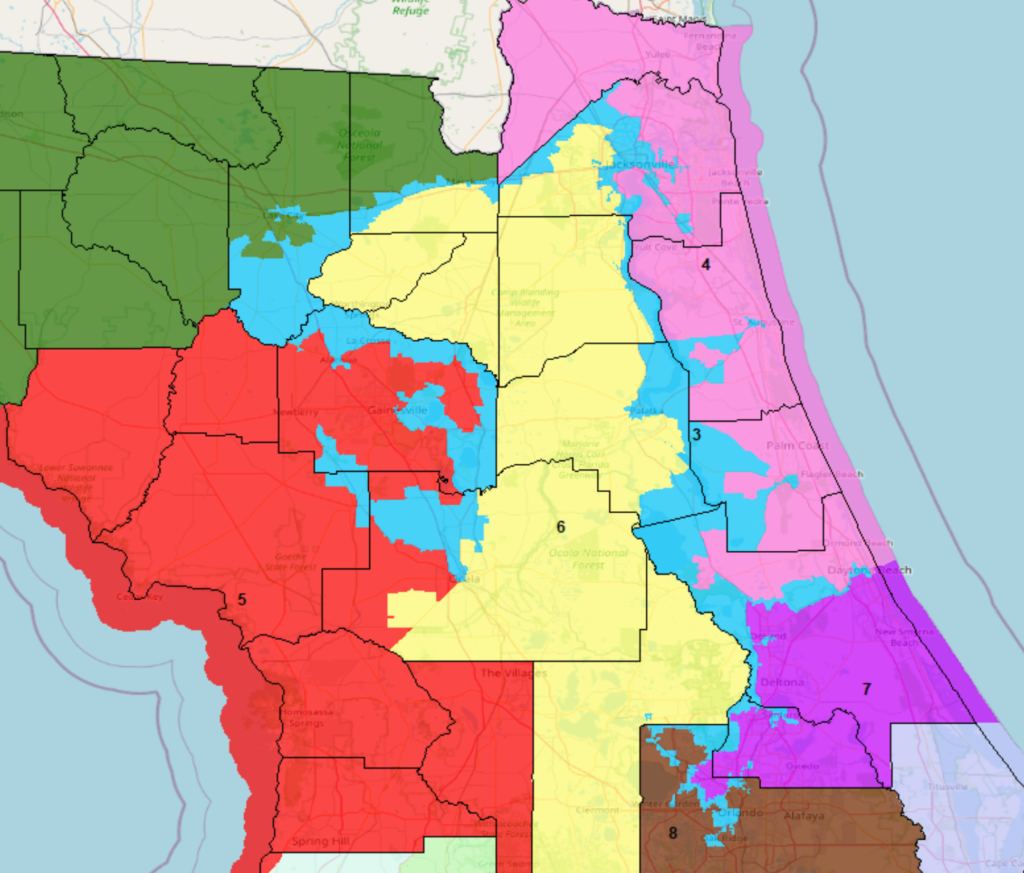

The new 5th layout led to a major reorganization of Orlando. In the new drafts, the new 10th district was set to be a deep-blue district with a 50% black democratic primary.

The map would result in effectively a 4th African-American district for the state. The 10th would indeed perform as African-American; electing Val Demings.

The Dynamics of the Current 5th District

Lets talk about the 5th in its modern form.

Black Population in North Florida

One of the issues that comes up a great deal in discussion around the 5th district is whether or not Jacksonville to Tallahassee is an acceptable distance. DeSantis and conservatives argue that the seat simply connects Jacksonville to Tallahassee and just splits counties all along the way. Well, that is part true and part false. Tallahassee and Jacksonville dominate the vote totals – but perhaps we should look more at those connecting counties along the way. The question being, why is this configuration even an option?

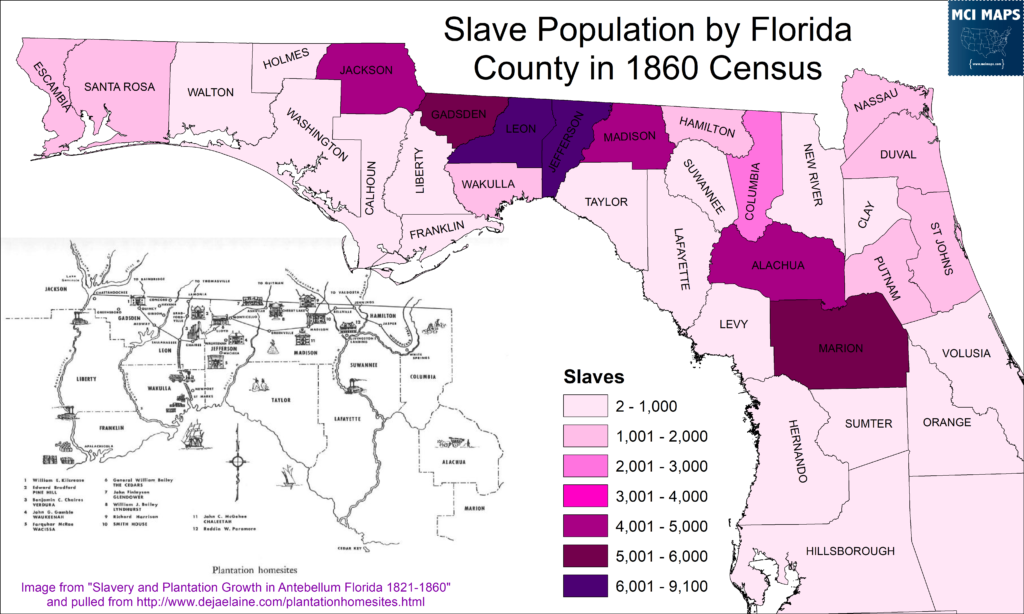

The answer is seen in the history of Florida; before the civil war. Florida, like the rest of the confederacy, was a slave state. The northern counties specifically were littered with plantations; with the highest cluster around the Tallahassee area. In 1860, this is how the slave population broke down by county.

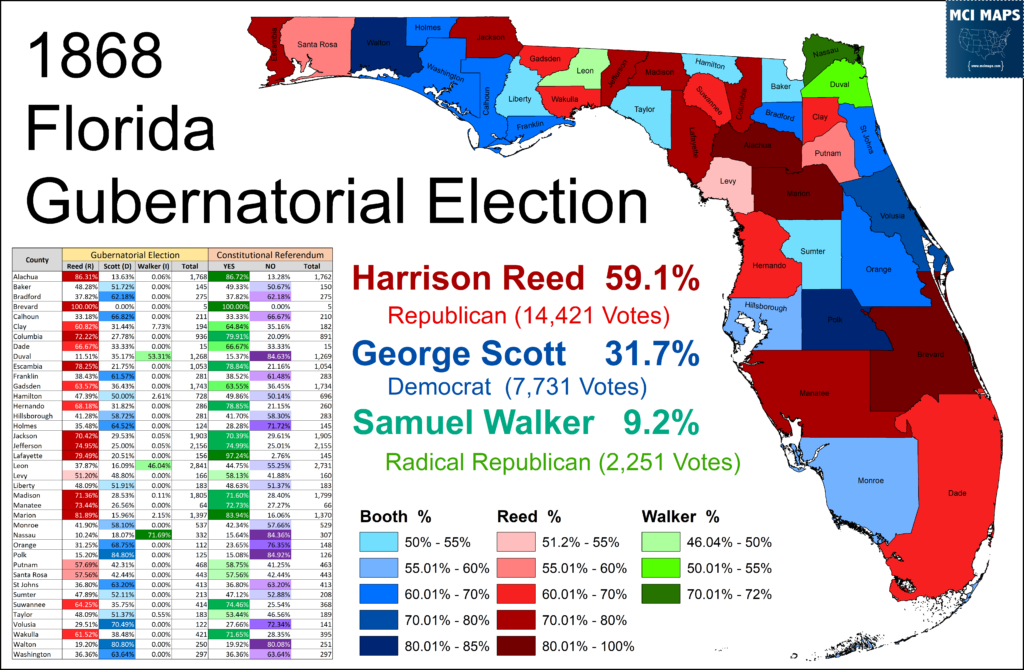

With the end of slavery but before Jim Crow came a time where newly-freed slaves exerted real power in North Florida. The northern counties were often Republican, thanks to steadfast freedman support, while African-Americans won local offices across the region. The 1868 Gubernatorial Election saw moderate and radical Republican candidates take many of the formerly slave-heavy counties.

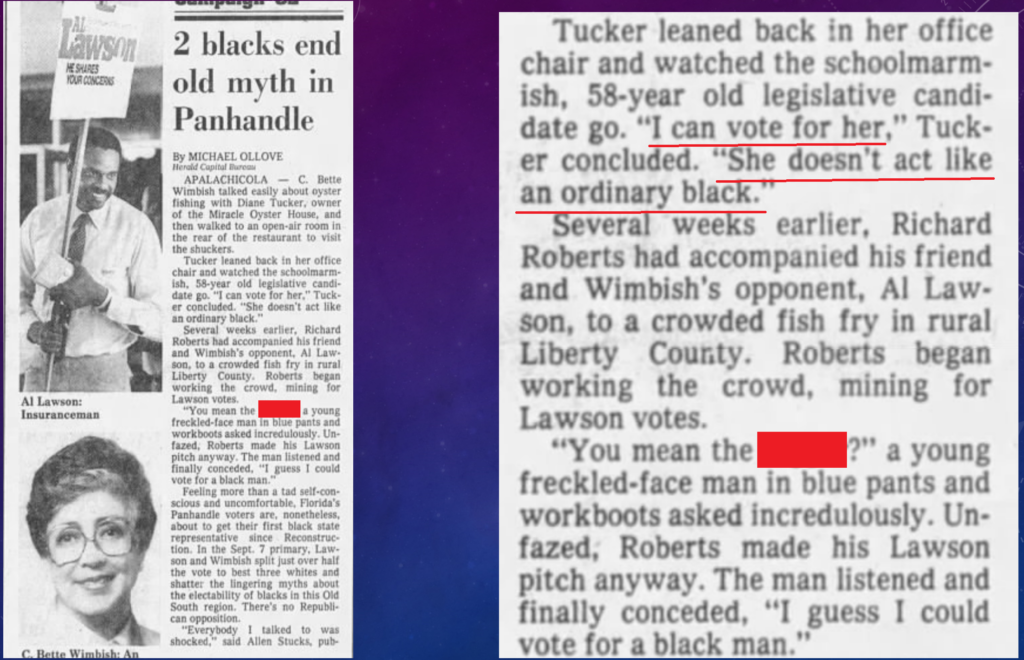

Then came Jim Crow and the suppression of black voting rights. It wouldn’t be until the 1970s and 1980s that black voting power led to local victories. 1982 saw the first African-American state legislature elected in the Florida panhandle, with Al Lawson securing a seat. I covered that race in my 1982 redistricting article. In that race, a runoff between Lawson and another African-American candidate led to some nasty campaign incidents in the rural white regions.

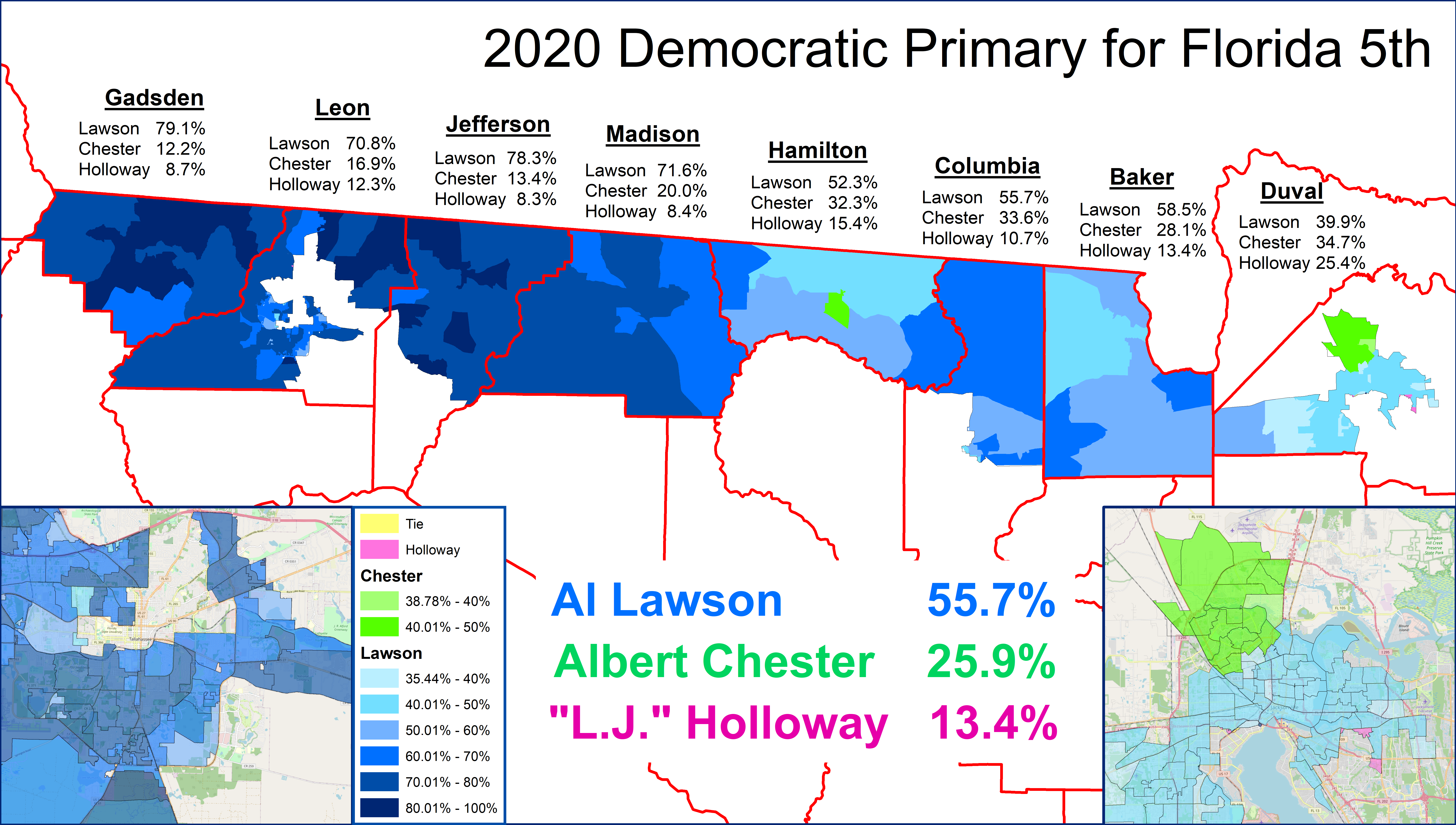

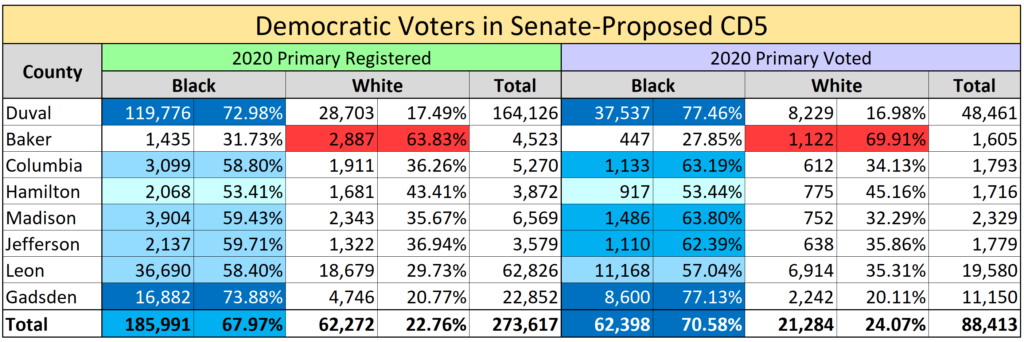

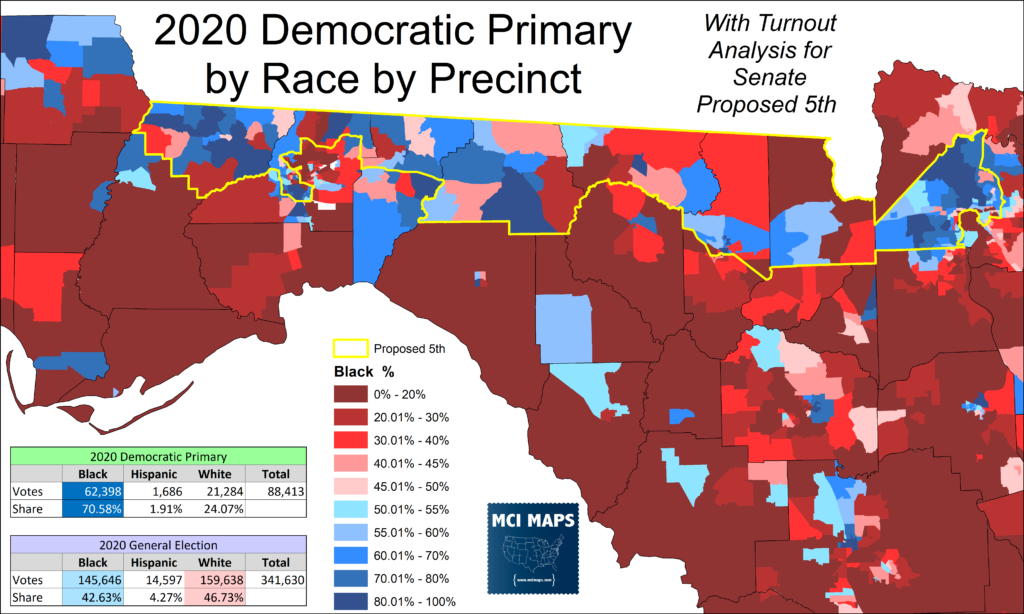

In 2020, the voting power of black voters, many directly descendent from the plantation systems, flourish in the panhandle. See below the racial makeup of the Democratic primary in North Florida, with the State Senate’s proposal for the 5th district overlaid.

Yes Jacksonville and Tallahassee dominate the district, but to act like no black voters exist in the middle is disingenuous. Only one of the counties in this district is less than 50% black in a Democratic primary.

The idea that this district merely connects two cities ignores the history of black voters in the rural panhandle.

Performance from 2016 Onward

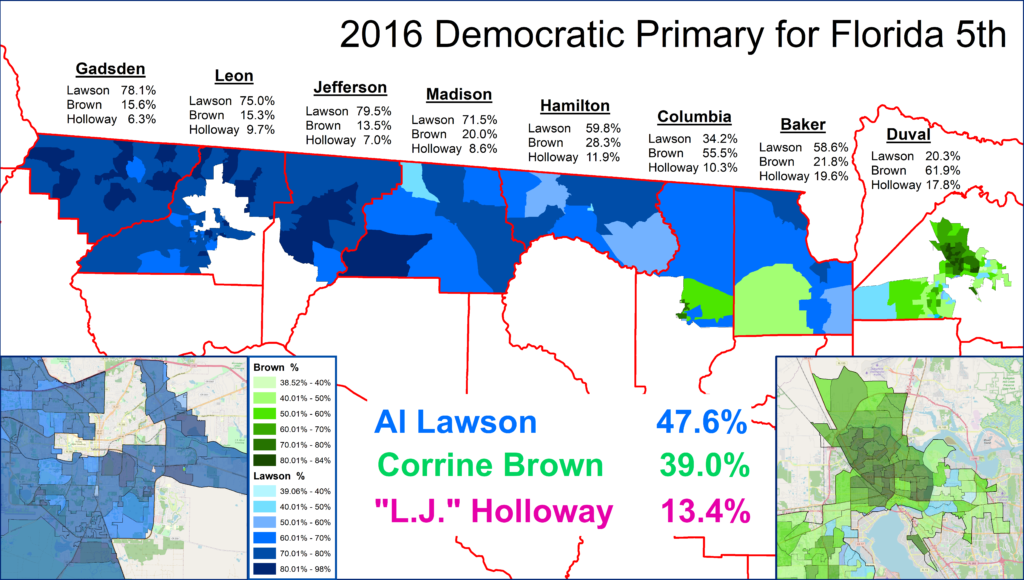

When the lines for the new 5th district were finalized, Al Lawson, now a former state senator, decided to run for the seat. After exhausting all her lawsuits, Corrine Brown filed for re-election. The primary turned into a very regional affair. Lawson represented much of the wester counties off an on from the 1980s through 2010. Brown, meanwhile, largely retained support in Jacksonville. Lawson would go on to win the primary thanks to dominating shares of the vote in the west.

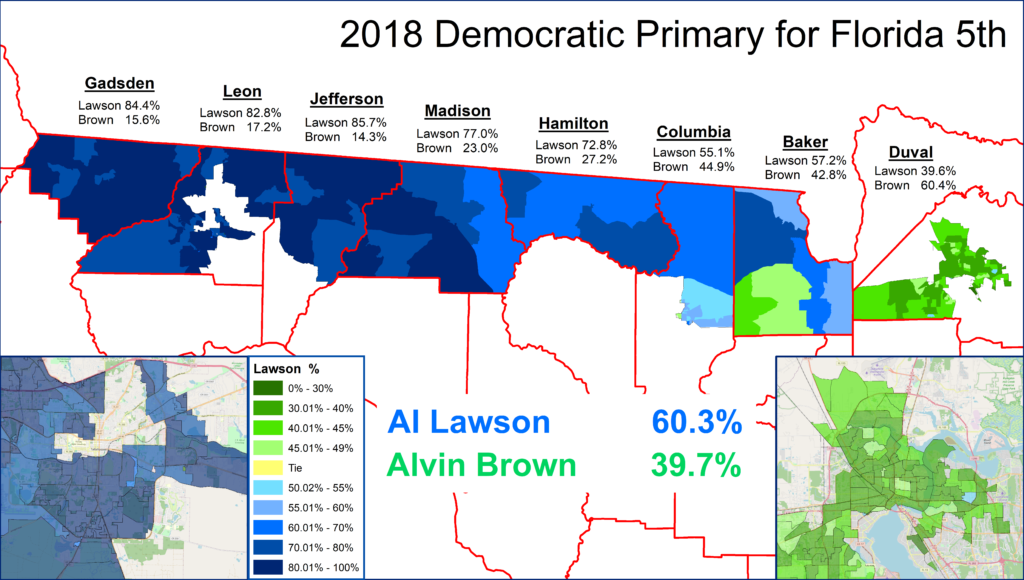

In 2018, Lawson faced another credible primary challenger. Jacksonville, still eager to win back control of the seat, supported former county Mayor Alvin Brown. However, Brown’s campaign faltered as time went on. Lawson had the western counties completely on his side, and Lawson was making inroads in Jacksonville. The beauty of the seat made itself apparent here. Lawson knew he had to show results for Jacksonville and could not ignore the area. As a result, Lawson worked hard over his first two years to be present across the district. As a result, Lawson generated plenty of local support in the east, and in the end took 40% in Duval. This doubled his 2016 share.

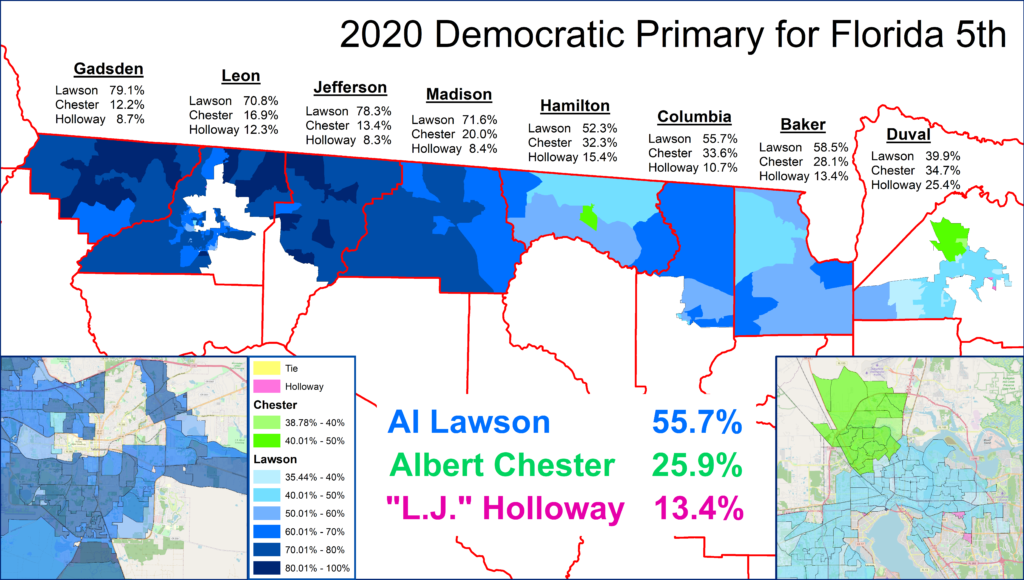

In 2020, Lawson again faced primary opponents but not from any major names. It was in this race that regionalism began to fade a bit. Lawson faced greater pressure for being less lefty than many other Democrats. Indeed Lawson has always been a bit more of a moderate Democrat (dating back to his first election); granted never being a problem in the caucus. Lawson’s primary opponents positioned themselves to his left. However, with split opposition, Lawson never really doubted his re-election.

Lawson continues to not “kill it” in Jacksonville, but his 40% in a 3-way is arguably better than his 2018 show. Lawson lost ground further west, but still largely dominated.

Current Redistricting Debate

As redistricting began for 2022 in Florida, the 5th district wasn’t even a source of debate. Lawmakers included a similar 5th in all their redistricting drafts and staff declared the seat protected. DeSantis and his conservative allies have gone after the 5th for a few issues. Let’s talk about these.

Is the Distance too Long?

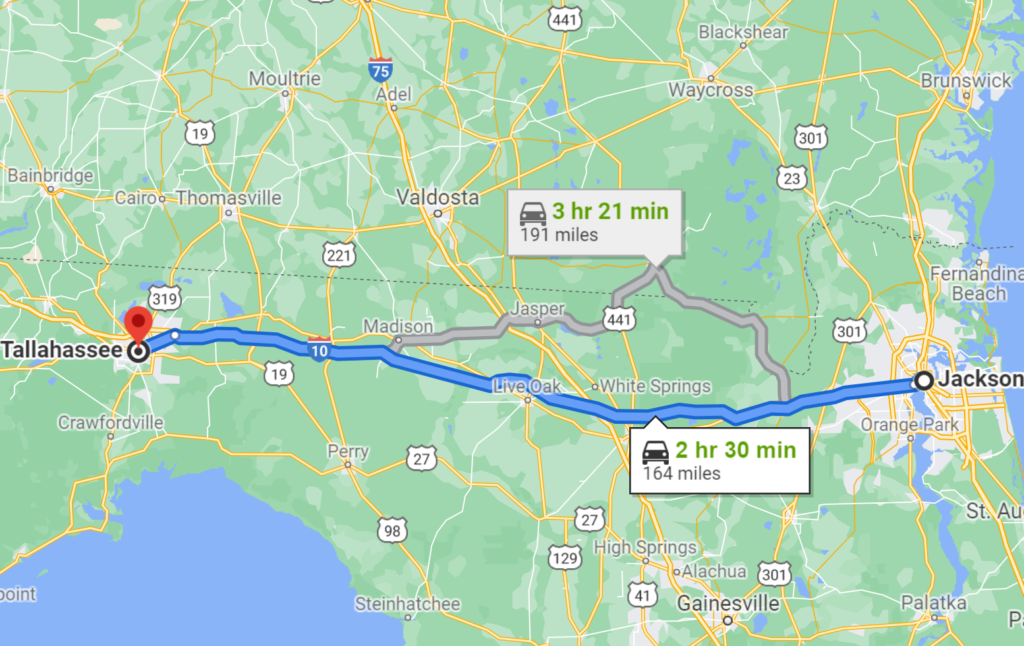

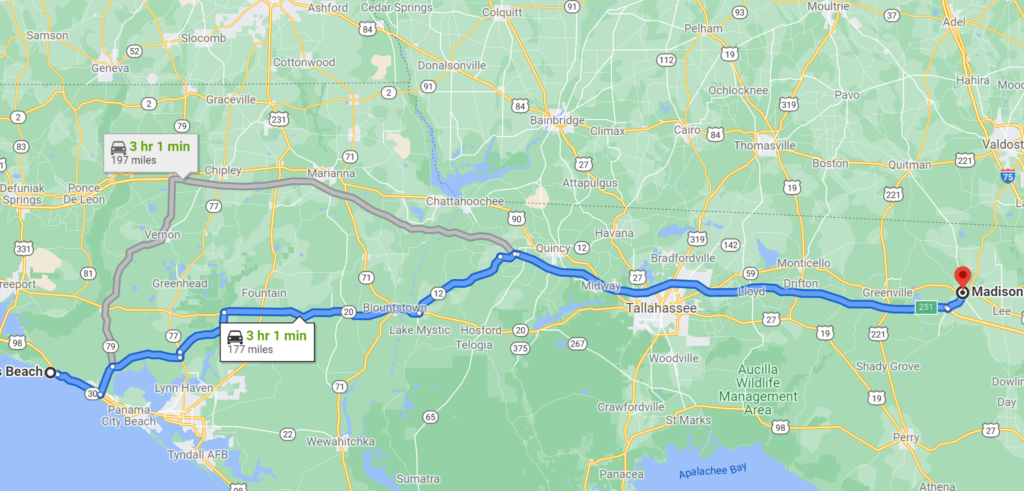

To me, the silliest argument against the current 5th is its “too long.” DeSantis’ office said the drive was a 2.5 hours from one end to the other. This is true.

Now, I’ve made the case that this isn’t just about two cities – and that those middle counties matter as well. However, beside that point, I’d like to note that CD2 in DeSantis’ plan has an even longer drive time from one end to the other.

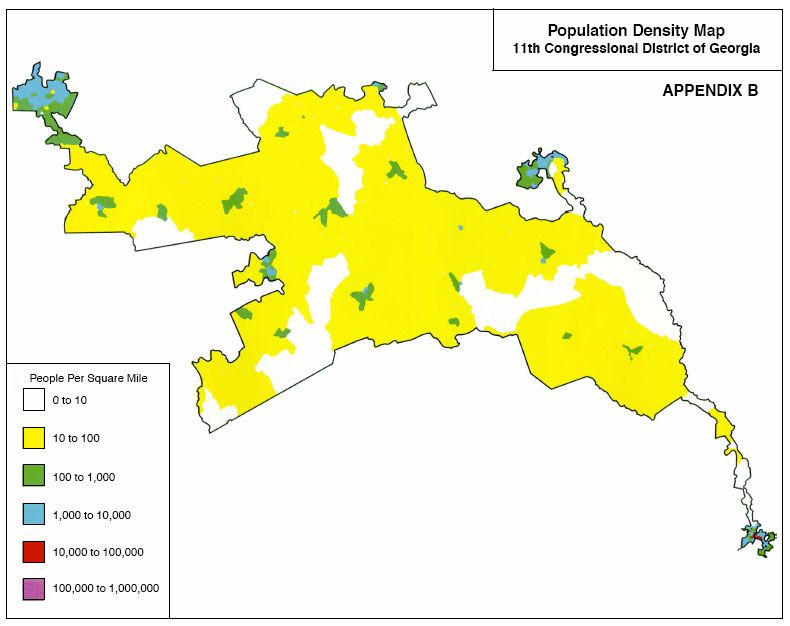

The point I want to make here is that drive time or distance, by itself, is not a valuable metric. Many parts of Florida, especially in the north, are low density. Districts often are large.

This is a fake issue.

Are Black Voters Divided?

One of the other talking points against the 5th is an argument that black voters are not united enough. This stems from a principle in redistricting, namely Thornburg v. Gingles, that one criteria for a minority seat is that the minority community has sufficient cohesion to elect a candidate of their choosing. A good example of this is a case from Hendry County and a suit over mandating single-member commission districts. The court found that black and Hispanic voters in the county did not have cohesion, impairing the ability to create a functional minority seat even if single-member districts were utilized.

In the case of the 5th, the primary maps showing Lawson trailing in Jacksonville have been used as an argument. This, however, doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. For one, all primaries have been held with only African-Americans running. This argument might hold water if white candidates kept winning due to African-American divide. However, all we have seen is that in races where minority representation is not in doubt, geographic allegiances arise. This by itself is not enough to argue a lack of cohesion.

Retrogression in Fair Districts

The biggest flaw in the DeSantis argument for his plan is that only African-American majority districts are protected in Florida. The conservative argument relies on the idea that a conservative court will interpret Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act narrowly, to the point where only 50%+ black districts are protected. In this case, the 5th and 10th wouldn’t be safe.

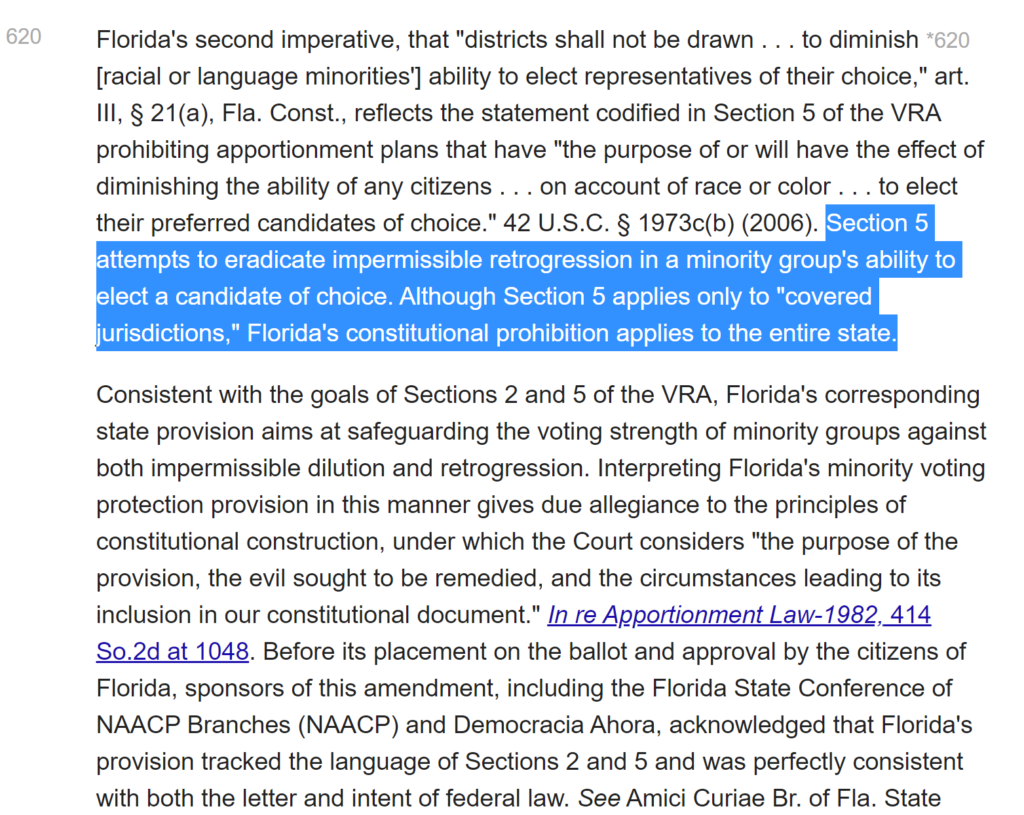

However, this is not the major legal point for us to focus on. Its not about Section 2 of the VRA, its about the Fair Districts Amendments. These measures are part of the Florida Constitution, and they incorporated a protection against diminishment of minority voting power, aka retrogression. This passage is from the Florida court’s 2012 review of the legislative plans.

As the court points out, the Fair Districts Amendments essentially added Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act to the Florida Constitution. While the US Supreme Court invalidated the formula used for Section 5 in 2013, it did NOT strike down Section 5. Regardless, Florida has added a Section 5-style protection against retrogression from its constitution. In basic English, the Fair Districts Proposals forbid shrinking the number of performing minority districts. Florida currently has 4 performing African-American districts. This cannot just be cut in half.

So what does this mean? It means that the DeSantis plan going from four African-American seats to two would be in direct violation of Florida’s Constitution. There is no legal argument for the DeSantis plan being compliant with Fair Districts.

What About the Conservative Court?

I’ll keep this brief because I don’t claim to be a lawyer. Much of the conservative retort to the above retrogression point is “that was an old liberal court!” This is true, as I wrote about here, the court in Florida now is much more conservative than the court of 2012 and 2015. However, while I and others have long imagined the new court would give more deference to the legislature than in the past, that is not what the DeSantis plan is about. This plan is extremely aggressive and blatantly violates the law. The assumption that the Florida justices would just sign off on whatever treats them more like political hacks than is warranted.

It should also be noted that the only way the courts will be deciding a Congressional plan this year is if a map cannot pass the legislature. The Senate has passed its map, and has made it clear they will defend their plan in court. I’d say the chances they take up DeSantis’ plan at 0%. The house could take up the DeSantis plan, or not. DeSantis could veto a plan he doesn’t like. The courts will only get involved with Congress if they must chose a plan. Its also not even clear that the Florida courts would hear the matter first. If a deadlock results, it would depend on who sues first and where. The understanding is Democratic-aligned plaintiffs would want to go before the federal courts, while Republicans would want to go before the state courts. This would start with a trial court or panel of judges, not right to the top Florida Court. I can actually say, having talked to lawyers that know this better than myself, the exact roadmap through the judiciary is hazy at best.

If the court is forced to get involved, they are going to go into it with the Senate, and possibly the house as well, arguing the 5th district is protected. That IS the position of both chambers as of this writing. That fact gives the court, regardless of which court it is, much more reason to not pick the DeSantis plan.

Conclusion

Oh what can I say to properly wrap all of this up? I would like to think I’ve made a compelling case for why the current 5th district is protect. Even if you don’t agree with me, hopefully you will have learned more of the history of this district and the intense redistricting debates of the past.

I’m quiet sure that when Ron released his plan, he gave zero thought to this history.