On May 22nd, Ireland became the first nation in the world to legalize same-sex marriage by popular referendum. The vote for approval was 62%, amazingly high considering Ireland’s reputation as a more conservative, Catholic nation. Polls constantly showed a major lead for the YES side of the referendum; which had the backing of all major political parties and prominent celebrities.

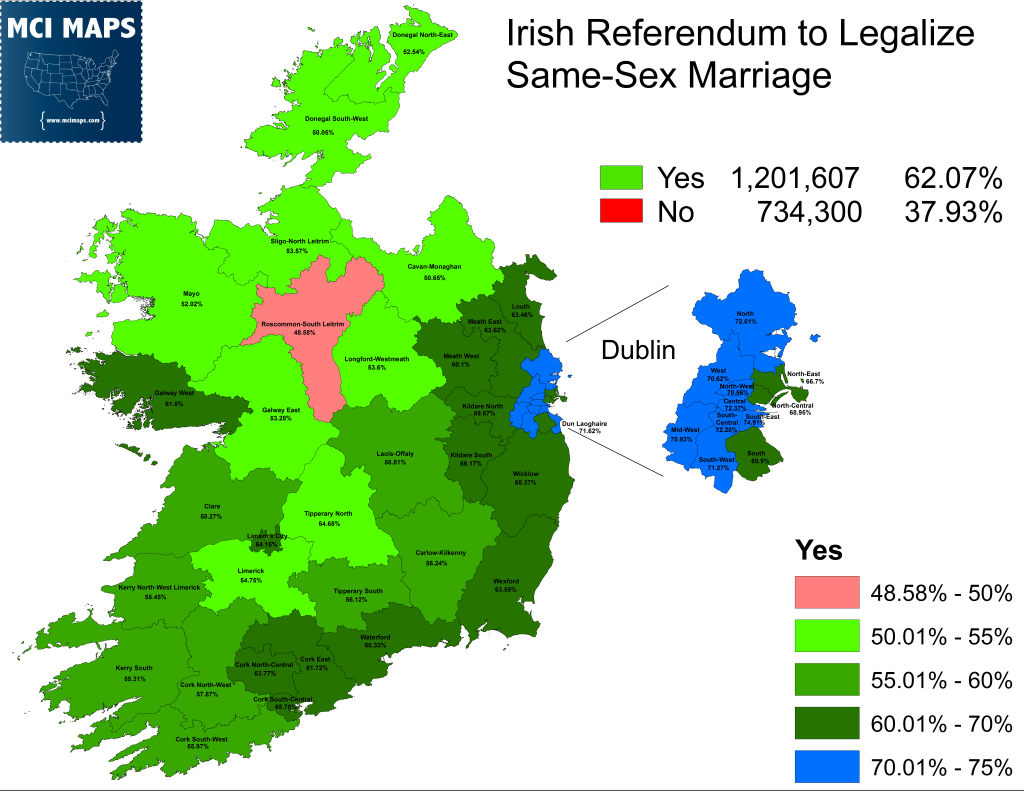

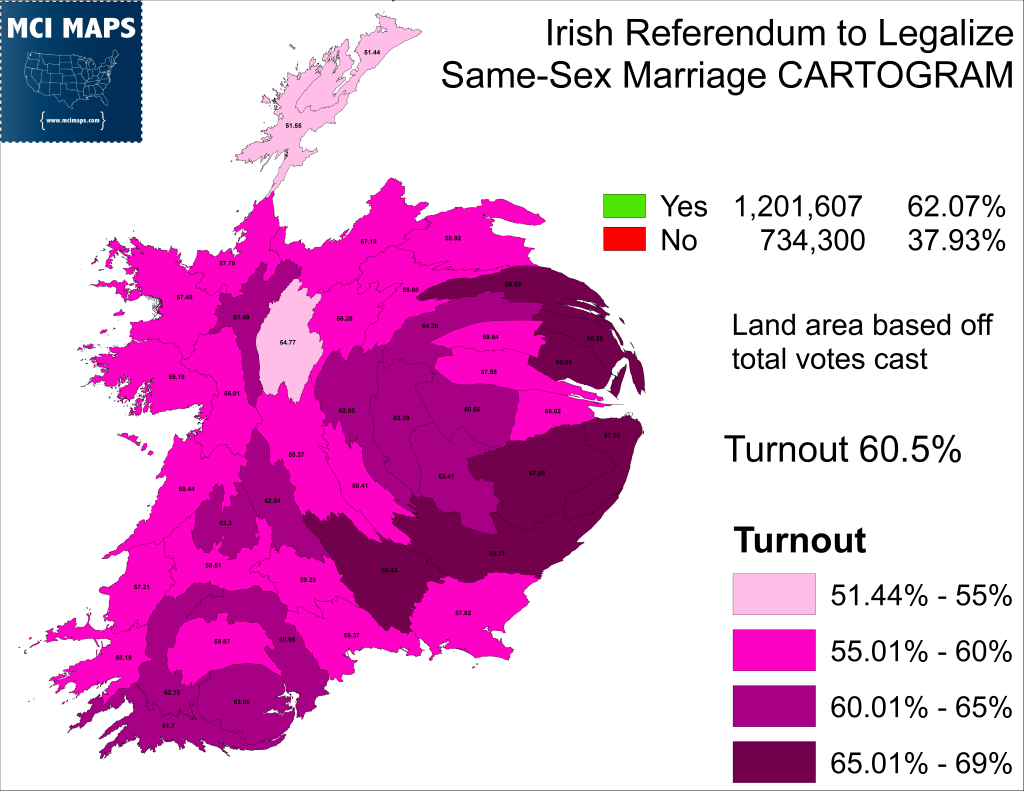

The measure passed in all but one constituency, the conservative region of Roscommon. Meanwhile registering over 70% support in Dublin. The strong showing, including wins in many rural/conservative constituencies in the North and Southwest, was a stunning testament to how support for same-sex marriage has skyrocketed in just the last decade.

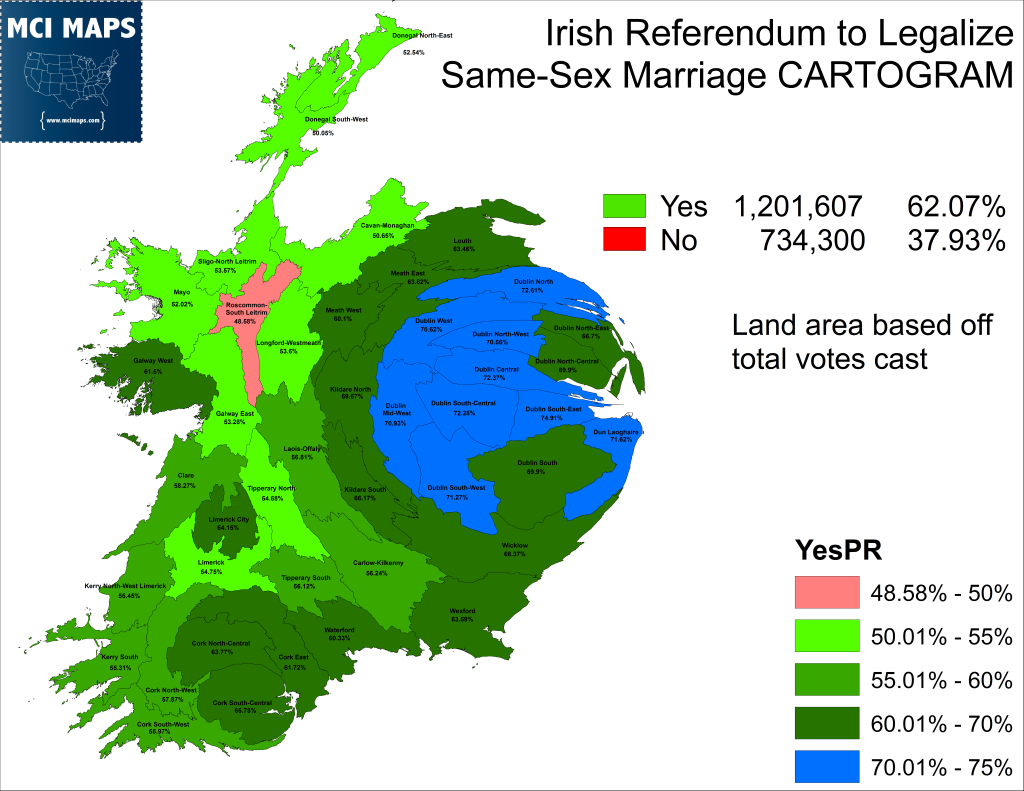

The cartogram map below shows each of Ireland’s constituencies reshaped based on the total votes cast in the referendum. Dublin, despite its small size, had 25% of the vote come from its constituencies.

The win for same-sex marriage was very impressive due to Ireland’s history as a more conservative, Catholic state. So how did such a strong win become possible?

The Campaign

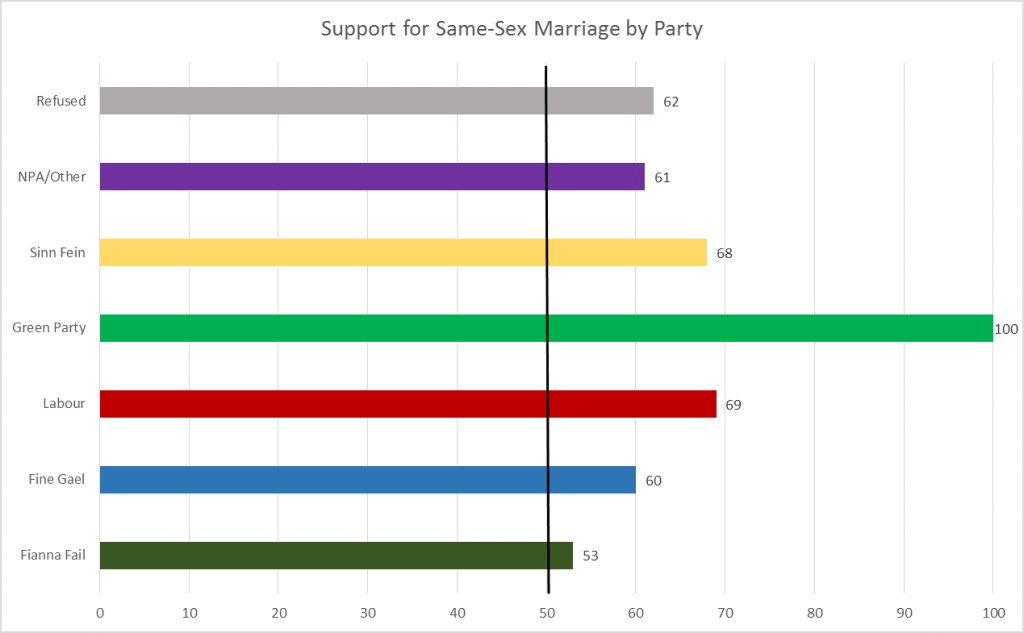

Once the referendum was scheduled, the YES campaign had a significantly larger amount of institutional support compared to the NO side. All of the major political parties came out for the measure, including the Incumbent Prime Minister and the former President. Both the Fine Gail and Labour Parties, who rule Ireland with a coalition government, as well as Sinn Feinn and Fianna Fail, who rule in the minority, supported the YES vote. A poll commissioned by the Sunday times showed support for same-sex marriage by party allegiance. All parties saw their members support the issue. The narrowest was for Fianna Fail, which was a conservative, center-right, populist-style party that appealed to rural Catholics.

The Press praised Fianna Fail for its support for the measure considering its base of support often came from areas less inclined to support the measure. However, one Fianne Fail Senator just announced she was leaving the party for many reasons, one being she felt the party did not campaign aggressively enough for the YES side. According to Senator Averil Power, many members of the party didn’t back the measure, and those who did affirm the individual support in private refused to campaign for fear of losing rural Catholic votes in the next election. In 2011, most of Fianna Fail’s best constituencies were the Northern areas, which backed same-sex marriage by the narrowest of margins. Fine Gail was also lukewarm on support at first, with Labour really pushing the referendum. However, once the measure proved to be popular, Fine Gail’s enthusiasm for the YES campaign grew.

The business community was also heavily in favor the measure, seeing it as a way to attract talent and other industries to the country. Major international companies and local corporations endorsed the measure. The major opposition group was the Catholic Church, but their opposition was much more tepid.

The YES campaigns worked hard to evoke emotion in the debate, running powerful ads and using personal stories to pull at the heart-strings of the voters. The NO campaigners tried to argue the family would be damaged by the measure. However, their arguments never resonated well with voters, especially in an era were other countries could be sited as legalizing same-sex marriage and showing no ill-effect. The YES campaign ran one of the best political commercials I personally have seen for such a measure, running a family-friendly ad that appealed to all segments of the population.

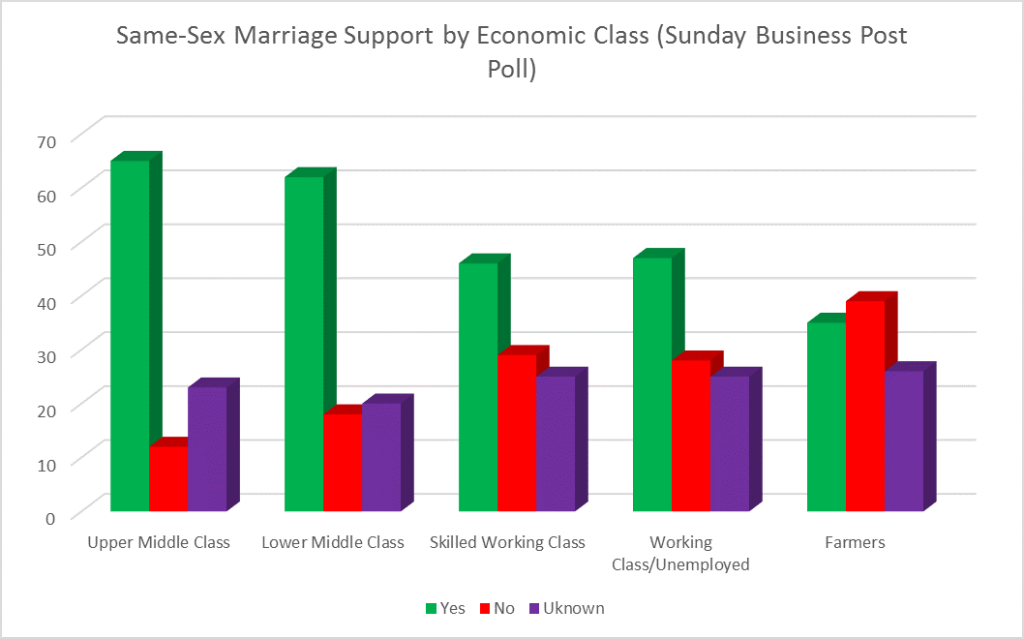

The YES campaign worked to reassure voters of all stripes that voting for same-sex marriage did not run contrary to the values they held. Whether it was the campaign or pre-held beliefs, there was not a great deal of class-divide of the issue. A poll commissioned by the Sunday Independent showed support for the measure across all class divisions expect rural farmers.

The poll’s nation-wide results were 53% Yes, 24% No, and 23% undecided (for reference). While upper and middle class voters backed the measure more, the issue still had support with working class and manual labor voters. Considering the strong win, its likely farmer’s did indeed reject the measure, but not overwhelmingly.

While the YES campaign had a great message and a well-energized team that canvassed neighborhoods and registered voters. The NO side was overall much more quiet. Some NO members were obnoxious, stereotypical fear-mongers. However, many of the NO campaign leaders were generally respectful, they just didn’t have a strong message to reject the measure. When the YES victory was clear, one of the major heads of the NO campaign tweeted out congratulations to the YES campaign. Many of the hostile feelings during these referendums that have taken place in the US did not occur in Ireland, at least not to the same degree.

The Youth Vote

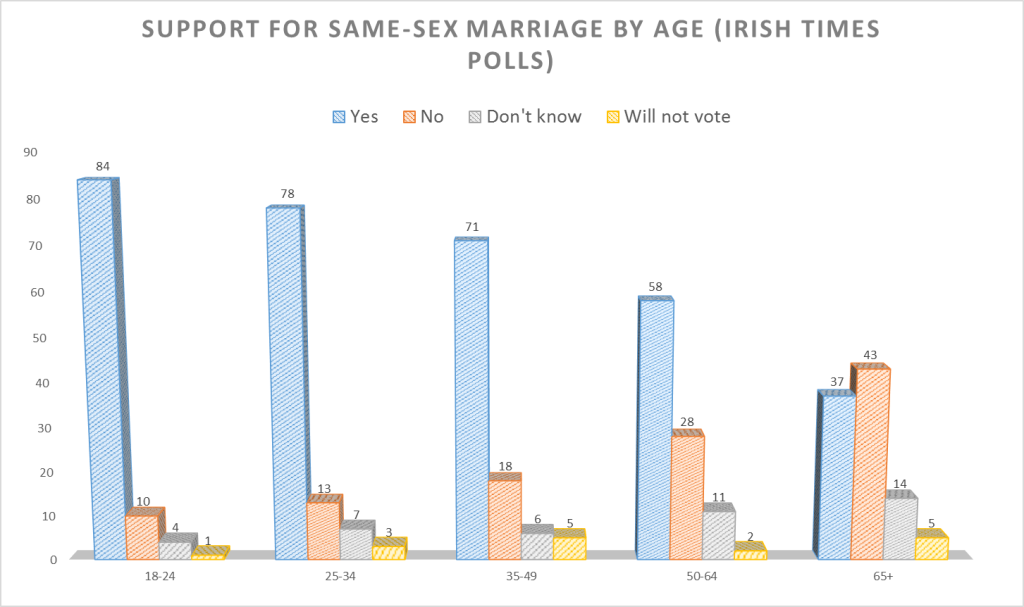

As is the case in America, the most supportive group toward same-sex marriage are young voters. A March poll, commissioned by the Irish Times, showed voters 18-24 registering 84% for the YES side of the referendum. For the YES campaign, ensuring young voters turned out would be critical in case the polling began to shift over the next two months.

The campaign worked to register over 60,000 youth voters in the last few weeks of the campaign, a monumental registration effort. In addition thousands of Irish citizens, many of them young, came #hometovote to cast a ballot in the referendum. Ireland does not allow vote by mail for those oversees, and the stories of people making the trip home became a sensation in Twitter and in the Press on the day of the referendum.

Polls leading up to election day showed that the support for same-sex marriage continued to be strong with youth and middle-aged and older voters, and narrowly trailing with the oldest sub-set of voters. In the end, if there had been issues with youth turnout, the measure still would have passed. However, the campaign made the right call in working to activate young voters as a way to ensure the measure had the breathing room if the polls narrowed. The success in activating youth voters, increasing registration and turnout, was a major accomplishment for YES campaign and something the political parties of Ireland will not doubt aim to take advantage of.

Turnout

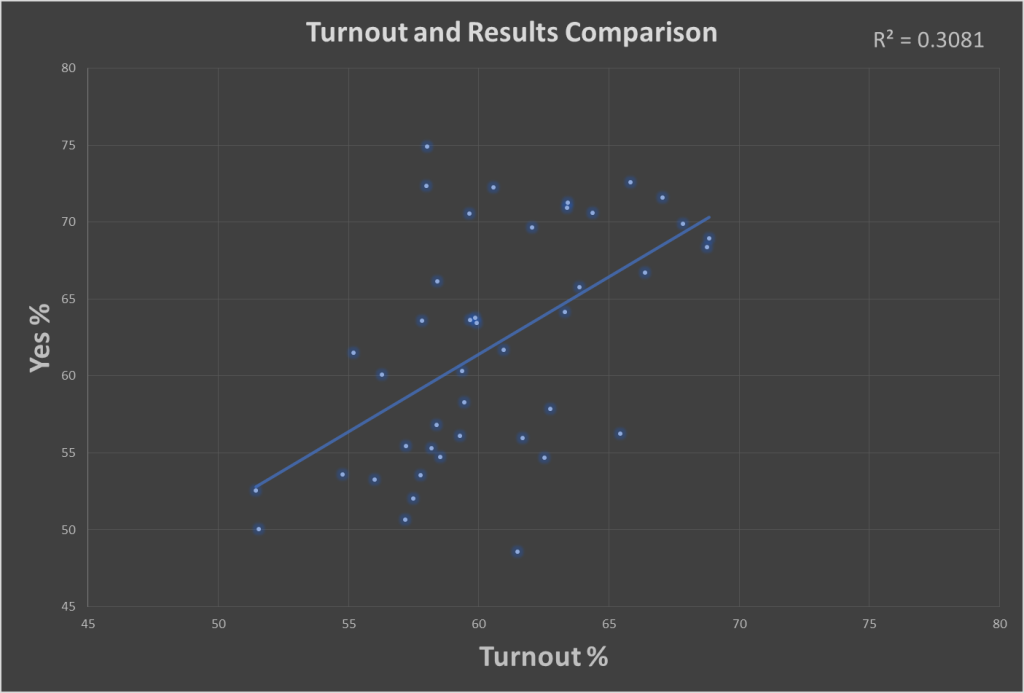

Turnout was very strong for the referendum, topping 60%, making it the highest turnout in the last 20 years. Turnout was very high in the Dublin region, an area critical for the YES campaign.

The margin was as strong as it was thanks to areas so supportive of the measure giving it such large support. In contrast, some of the weakest areas for the YES campaign also had lower turnout. The correlation is not especially strong, but it is noticeable. Areas more supportive of the measure also happened to have higher turnout.

Again, the correlation isn’t very strong, many areas show high turnout with more modest support or show strong support with modest turnout. However, there is a clear trend-line linking support and turnout to some degree.

The Church’s Tepid Opposition and Decline in Influence

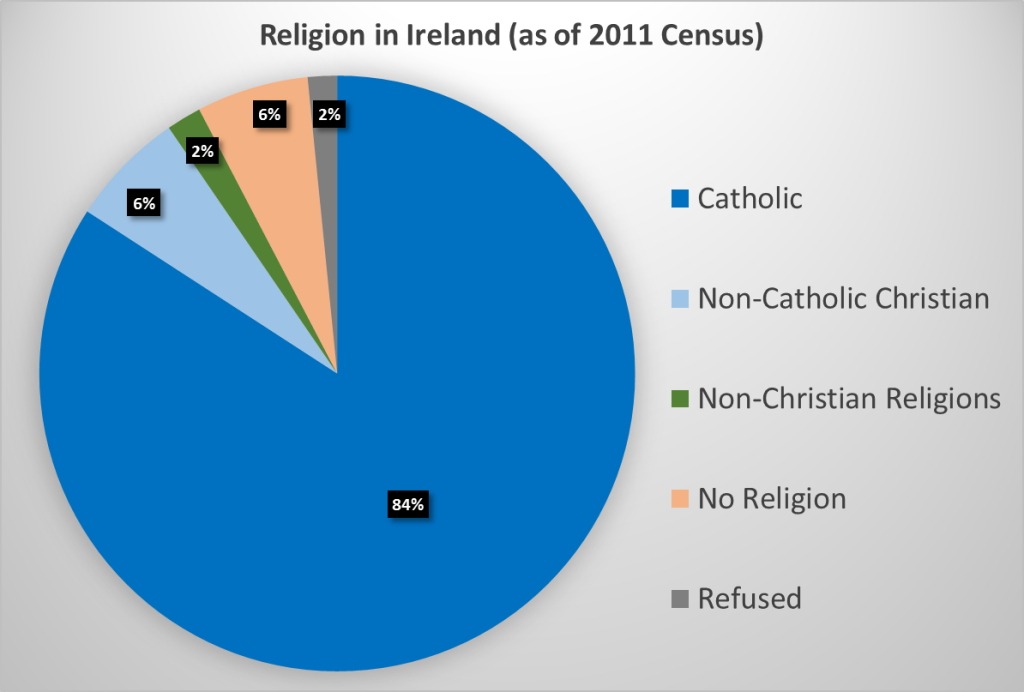

The biggest contradiction to Ireland’s support for same-sex marriage was the fact that Ireland is so overwhelmingly Catholic. As of the 2011 Census, 84% of Ireland identifies as Catholic, with 90% identifying as Christian.

In the aftermath of the referendum, many who followed the campaign have noted that while the Catholic Church took a position against the YES campaign, passing out a message for the Priests to read the Sunday before the election, the opposition was much more tepidthan in the past. The Church took a much stronger role campaigning against the 1995 referendum to legalize divorce, causing it to pass by only 0.6% despite leading polls by a large margin. The map on the divorce referendum is below. The map is from Irish Political Maps. I highly recommend you check it out, the site has a great deal of maps and history of elections in Ireland going back as far as its time as British colony.

As the map shows, most constituencies rejected allowing divorce, with the measure only passing thanks to major support in Dublin and tepid support in other cities. Many areas voted heavily against it. Let me put up the same-sex marriage map again just to contrast how much has changed. These were both issues rooted in religion and dealing with marriage; both with Church opposition. However, the maps are radically different. Areas that heavily rejected the divorce referendum supported same-sex marriage, even if with just modest approval. It is a remarkable turnaround.

During this referendum, the Church’s opposition was fairly muted, not coming out till just before the vote. The Church stated its opposition but the Church Leaders in Ireland did not decree/urge voters to cast ballots for the NO camp, leaving the decision to the individual. The Archbishop of Dublin, an opponent of a YES vote, made headlines foradmonishing those who used a harsh tone toward LGBT people. Many Church leaders were noted for demanding civility and decrying homophobia as un-Christian. While the Church sought to keep marriage as it was, it went out of its way to say it did not want to deny LGBT people the rights the desired. Like the 1995 referendum on divorce, the Church did not state that supporting the position contrary to the Church was considered a sinful act. The tone during the campaign further highlighted a growing evolution on gay rights within the Catholic Church, especially in the wake of Pope Francis. Many otherprominent religious leaders in Ireland, including those who advocate for the homeless, backed the YES campaign. As the Washington Post said, these local leaders had more moral authority in the eyes of the voters than the Catholic Church hierarchy.

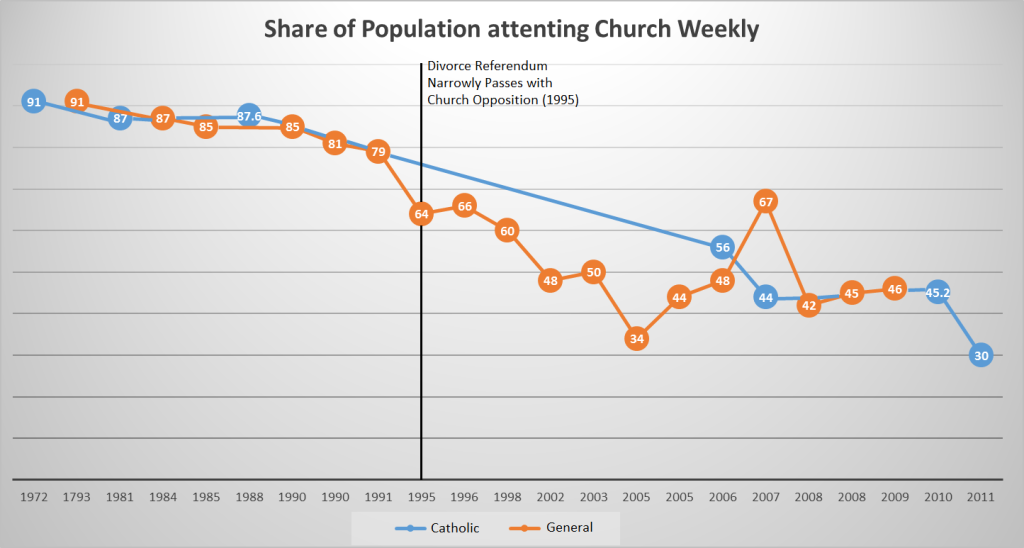

Another factor that cannot be overlooked is that the Catholic Church’s authority has been greatly weakened in Ireland. The Priest Sex Abuse scandal has had a major impact in Ireland and has soured the public’s image of the Church, weakening its moral authority. Weekly Church attendance is also at a much lower point than it was over past decades. The line graph below shows the percent of the population attending Church weekly. There is less data for Roman Catholic specifically.

Despite a bump in 2007 (which may be an outlier), the percent of those attending Church weekly has declines greatly over the last 25 years. I pointed out the divorce referendum on the timeline to show how much higher Church attendance was then compared to now.

The decline in Church attendance does not mean Ireland is becoming less religious necessarily. Most of the population still identifies with the Church. However, it does mark a shift from a society that used to revolve around the Church. The YES side could not have won without religious voters. Indeed, according to one of the last polls released (by the Irish times), 45% of voters who planned to cast a YES vote considered themselvesreligious. Of course what “religious” means is open to debate, but the fact is those voting YES did not consider themselves anti-religious or ambivalent. Irish Catholics are clearly moving in a more liberal direction, something reflected in America, where 57% of Catholics support same-sex marriage as of 2014. The Church’s tepid opposition and weakened authority no doubt made it easier for devout Catholics who wanted to support the YES campaign to do so.

Was There a ‘Shy No’ Vote?

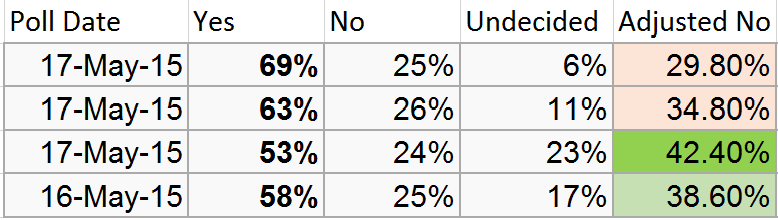

One issue that came up in the last few weeks of the campaign was a concern that the polls, as few as there where, would be wrong. The issue was reflected in past polling on referendums proving to be inaccurate, especially when on sensitive issues. Notably, Ireland’s 1995 vote to legalize divorce passed with 0.6% of the vote after holding massive leads in the polls. A more recent poll to abolish the Senate failed despite holding a comfortable lead. The press began to pick up on the notion of whether or not their was a ‘shy no’ vote, people unwilling to tell pollsters (some of these polls done in person) they would vote no. The issue of a ‘shy no’ voter came from the fact that the YES campaign used a very emotional and effective narrative to persuade people to vote yes. The concern was that opponents of the measure would have feared being labeled intolerant or homophobic, and thus kept their opposition to themselves. When the vote came in with 62% support, it seemed the concerns of a ‘shy no’ vote were unfounded. However, looking closer at the polling, it appears their may have been a ‘shy no’ vote after all.

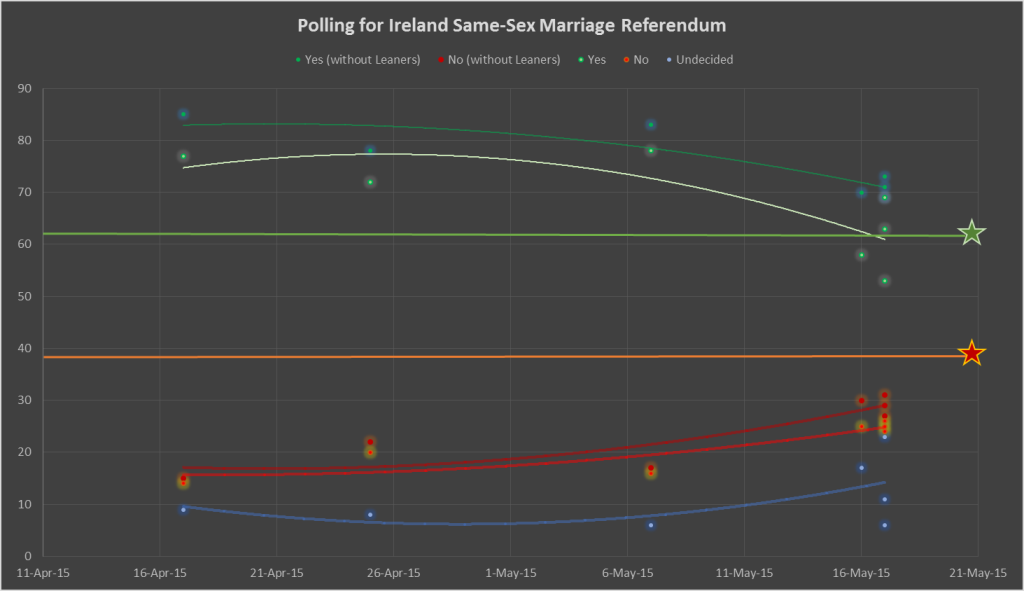

The graph below shows the polls taken over the last two month. The dots show the poll results, the line represents the trend. In included two results the pollsters gave: one where they asked voters YES, NO, or UNDECIDED, and the other where they gave results while excluding the undecided. The decision to include the results that didn’t count undecided was made because there is always a possibility that many undecided voters simply did not go and cast ballots. Studies have shown many undecided voters stay home if they cannot make up their minds on candidates/issues. These studies are American-voter focused, so it cannot be assumed the same applies in Ireland.

In the last days before the campaign, four polls came out, three on the 17th. The YES campaign maintained its lead, but things appeared closer than in past weeks. When undecideds were counted, the YES campaign fell below the 62% they eventually won (represented by the straight green line). When undecideds were taken out, YES support remained high 60s and low 70s. Meanwhile, the NO side never really topped 30%, staying well below the 38% they got (represented by the straight red line).

If we were to say there was no ‘shy no’ vote, then how do we get to 38% opposition. Using the last four polls, all of which came as the heels of the vote, I tried to find a way. I took the NO percent for from each poll and added in 80% of the undecided vote to the NO camp. Studies in the US have show undecideds in referendums, if they vote, tend to break for the status-quo. 80% is probably more generous than reality, however.

Even when using 80% of undecideds voting NO, two of the polls still don’t have a high enough NO vote. The May 16th poll comes in just right, while the May 17th poll that showed an unusually high number of undecideds wouldn’t need it as high as 80%. Could it be that the May 16th poll or the May 17th with high undecideds be right? It is possible. However, this assumes all undecideds would actually vote and none would stay home. The May 17th poll could be right if undecideds gave 60% of the vote to the NO camp. However, I do find it suspicious that so many would be undecided so close to the vote, which no one else saw. In addition, that pollster showed 29% of those 18-24 voters undecided, while every other pollster showed major support and little undecided among that group.

In the end, without a better understanding of Irish pollsters and their rankings in accuracy, it is hard to say for sure how much of a shy no vote their was. I am inclined to believe, based on the data, that undecideds broke against the referendum in the end. This is based off past studies showing undecided vote status-quo. Cross-tabs from the pollsters generally showed rural, farmers, and older folks made up a larger share of the undecided vote, groups more likely to vote NO than YES. However, the undecideds would have been forced to break overwhelmingly no, and this assumes others just didn’t stay home. I believe their had to have been a minor ‘shy no’ effect to make up the difference. However, this vote was clearly minimal, and didn’t effect the outcome similar to the Divorce referendum from 1995.

Conclusion

The Same-Sex marriage referendum in Ireland marks a major achievement for the equality movement worldwide. Ireland’s vote broke stereotypes and provided a justification for other countries and their political parties to move forward on equality. Northern Ireland and several Western European countries that do not have marriage equality will now feel pressure themselves to move forward. The fighters for equality in those countries will have an example to look to as they wage their own campaigns of the coming years.